Grading Systems Are Stupid. But If You Use One, Use Ours

Tired of bickering over climbing grades? Then check out this new, streamlined rating system.

On a bright, sunny January Sunday, a small crew of us found ourselves bouldering at Carter Lake, a reservoir in northern Colorado with a ridge of Dakota sandstone blocks overlooking the water. Once a "poor man's Horsetooth"--scruffy, scrappy, chossy, and semi-abandoned--Carter has in recent decades come into its own, and for the most part the problems are now well-traveled and clean.

It was also one of the first bouldering areas I visited in Colorado, in summer 1989 during a trip through the state. Two friends and I came out on a June morning, navigating the blocks with a Bob Horan guidebook that featured hand-drawn topos. The book, as per the era, used the old John Gill B-Scale for ratings:

B1: A difficult problem, featuring moves as hard as the hardest done on a rope--around 5.10 at the time Gill devised the scale, in 1958.

B2: An extremely difficult boulder problem--moves harder than those done on a rope, so a specialist's bouldering problem.

B3: A problem done only once--the very limit--or, as Gill wrote in his 1969 essay "The Art of Bouldering," that is "very rarely repeated, although frequently tried without success."

Out at Carter in 2022, my friend Paul, who's old school like me and remembers the days of the B-Scale, and I started riffing on bouldering ratings and the elusive B3 grade. B3 was more a romantic ideal than anything, and I recall there being very few B3s--if any--when I started climbing in the 1980s. Paul said he'd repeated a John Yablonski B3 in Joshua Tree, near Intersection Rock--"not because it was the hardest thing around but mainly because no one else had bothered to try it," he recalled. We tried to think of modern-day B3s. Burden of Dreams and Return of the Sleepwalker, both V17 and, at the time of this writing, both unrepeated, fit the bill, and certainly there are others.

Paul and I waxed nostalgic, reflecting on a simpler time when splitting hairs over V-Grades wasn't a thing, because there were no V-Grades--though of course there was the Yosemite Decimal System, and all the ongoing bickering over letter grades and slash grades and plus and minus grades, blah-blah-blah, ad infinitum, ad nauseum.

This article is free. Please support us with a membership. Join the Climbing team and you'll not only receive Climbing in print, plus our annual special edition of Ascent, but you'll enjoy unlimited online access to thousands of stories, news and safety articles.

Grades Are Boring

At least for me, nothing is more boring or trite or short-sighted than haggling over grades. It's just ... dull, the dim province of small minds. Grades are estimates and are subjective anyway; they are not objectively quantifiable, say, like one's time for the 100-meter dash. Getting hung up on grades (and points and scorecards) detracts from the point of climbing--I'm out there for the experience, not to do bozo math. Grades also seem to be tools, wielded by the insecure, to inflate one's ego, especially in the case of downrating.

Let me give you one example of grade myopia, among so, so many: Last spring, my friend Ryan and I were up at a quiet wall high in the Flatirons, trying a project we'd bolted. Two bros showed up, "friendly enough," and then one of them redpointed a climb on the left side of the wall. As he lowered, instead of saying "What a great route," or "I'm psyched," or even nothing (what a concept...), he instead launched into a loud, chest-thumping sermon about why he thought the route was 5.12c, and not 5.13a or 5.12d as it's more commonly called. That's what mattered most to him: not the experience of the climb, but what he thought the grade was--as if this somehow mattered to the rest of us. Ryan and I gave each other a look then carried on climbing. This guy was beyond hope.

And don't get me started on the online pontificators who, for seemingly as long as the internet has existed, have been spewing on and on about how such-and-such a route is only "Gunks 5.8+" or "Eldo 5.9" or "Southern California 5.10c." (Maybe their painter's pants and over-the-shoulder chalk bags are cutting off circulation to their brains--who knows?)

Well, if this is the kind of behavior you're sick of at the rocks, then I have a solution! A brand-new, close-ended rating scale that, like the B-Scale of yore, is specific enough to be somewhat helpful but also squishy enough to prevent grade-bickering and ego-downrating. That's right, it's the "Jimmy Z Scale," named for a buddy I went to college with.

The Jimmy Z Scale

"Jimmy Z" was a nickname for a member of our college bouldering and Rifle crew, Jim, who hailed from Tennessee and had the thick Southern drawl to prove it. Tall, lanky, and with freakishly strong fingers, Jimmy Z would emerge from months of obscurity--snowboarding or raving or beach-hopping or some shit--and burn you right-the-fuck-off. He was just one of those freaks who could always crimp down--or, in his words, "Crimp tough." He also seemed to have his own way of looking at difficulty, or at least verbalizing how he viewed it. If not necessarily a formal grading scale, it was at least a loose philosophy. Here, the ratings:

No Big Deal (NBD): Not that hard; either flashed the climb or fired it in a couple of tries.

Pretty Burl (PB): Had to try fairly hard; the route or problem did not give up without a fight.

Burl (B): A very difficult climb--as in, "Man, that thing's burl." May or may not be sendable.

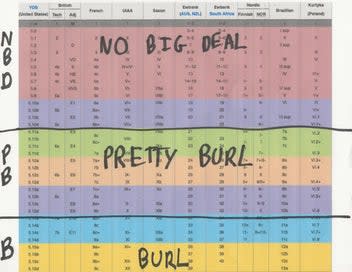

So there you have it, three simple, easy-to-understand ratings: NBD, PB, and B. To make things even easier, I have superimposed them on a ratings chart of all the various systems, so you can see how they compare. But here's the catch: These are just lines that I drew. For the scale to be universal, we each need to draw our own lines, moving them around on the chart as needed--the Jimmy Z Scale is all about personal grades. In other words, one year into your climbing career, 5.7 might be NBD, 5.10 might be PB, and 5.11a might be B, but 10 years in, 5.11a might be NBD, 5.13a might be PB, and 5.14a might be B--the scale evolves with you.

Moreover, the Jimmy Z Scale can even vary from day to day, depending on how well you’re performing. Which is to say, on any given day, you can climb the very hardest grade--Burl--if you feel that the climb you're trying merits it. This is the beauty of the scale: You always get to feel good about yourself, and no one can downgrade your project because whatever feels hard for you is either Pretty Burl or Burl (hey, it's up to you!).

If this scale sounds confusing or too fluid, consider that it's no more or less arbitrary than any other rating scale--for instance, a decimal system that goes well past its logical endpoint of 5.9 and subdivides into weird-ass letter grades, or a bouldering scale devised at one single area, Hueco Tanks, three decades ago. And if keeping track of grades remains important to you, then you still can, even with the Jimmy Z Scale: Simply print up the grade chart at Wikipedia, have it laminated, and carry a dry-erase marker with you at all times, moving your "Jimmy Z" lines around on the chart while you climb. And remember, Burl will always be Burl and no one can take that from you--even if your project would probably only be Pretty Burl at the Gunks.

Matt Samet is the editor of Climbing.