Former NFL player Greg Clark had CTE when he killed himself: 'Got to find better ways to help'

DANVILLE, Calif. – Carie Clark stepped into the backyard of her 4,000-square foot house last week and pointed to a flat-screen TV. It was mounted to a redwood tree in front of a hammock, once frequently occupied by her husband, Greg, who played tight end for the San Francisco 49ers from 1997 to 2001.

“He watched the football games from there,’’ Carie Clark said. “This was his heaven. Never in his right mind would he have left this.’’

Greg Clark killed himself in July with a gunshot wound to the head. He was 49 and died inside the house in northern California where he lived with his wife and their two sons – McKay, 14, and Jayden, 22.

Though his football career was cut short by injuries, his love of the game – and memories of his playing years – endured.

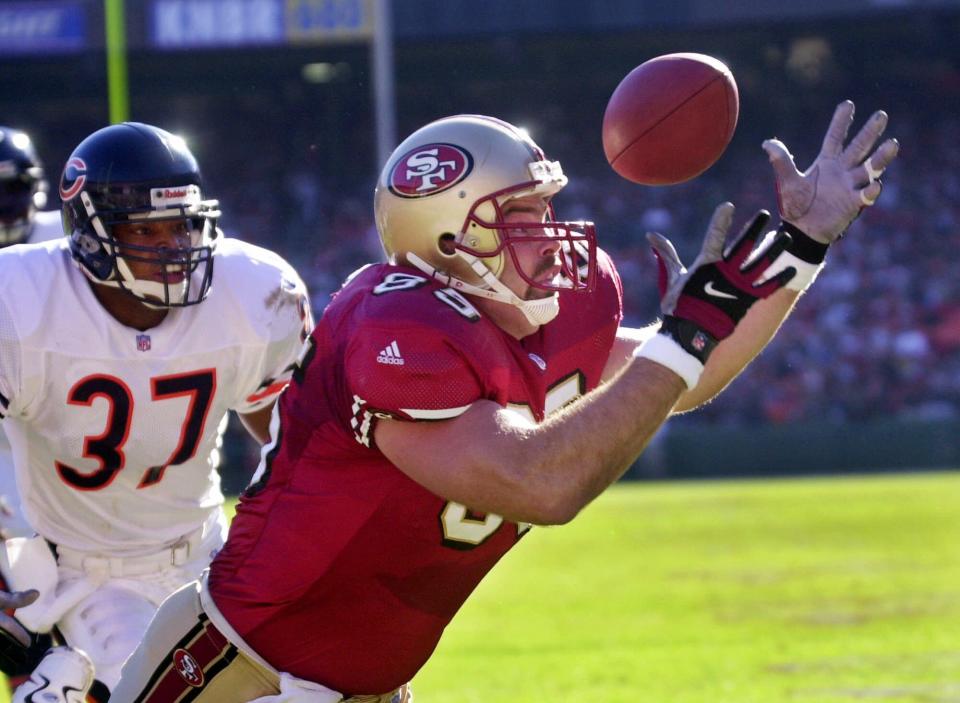

During the 1998 NFL playoffs, Clark caught two touchdown passes from quarterback Steve Young in a 30-27 victory over the Green Bay Packers. That next season, in a game against the Minnesota Vikings, he played with a collapsed lung.

Brent Jones, the former 49ers tight end, was a 12th-year veteran when Clark joined the team as a third-round pick out of Stanford, and he has described Clark as "relentless.''

“Relentless in his study, in his work habits, in his route running, all these things," Jones said during a eulogy at Clark's funeral. "But the thing that stood out to me is he was a genuine person."

Clark was also struggling mentally and emotionally in the last few years of his life, and it is now clear why: He had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Ann McKee, a neurologist who is director of the CTE Center at the Boston University School of Medicine, studied Clark's brain and shared the results with USA TODAY Sports and the San Jose Mercury News.

McKee, who completed her work in March, said she classified Clark's brain as CTE stage III, with stage IV being the worst. “His was fairly advanced,'' McKee told USA TODAY Sports.

CTE, a degenerative brain disease that can be diagnosed only after death, is associated with repeated blows to the head and with symptoms such as depression, aggressive behavior and, in some cases, suicidality.

With the diagnosis now official, Clark has become at least the 13th current or former NFL player known to have had CTE when they killed themselves.

Other players include Junior Seau, a Hall of Fame linebacker who starred for the San Diego Chargers; Dave Duerson, a four-time Pro Bowl strong safety who won two Super Bowls; and Aaron Hernandez, a tight end for the New England Patriots who died in prison after being convicted of murder.

"We just can't have this keep happening," Carie Clark said.

'I still love football'

Greg Clark’s story is about more than the risks of playing football.

It’s also about how 20 years after the autopsy of former Pittsburgh Steelers center Mike Webster began to raise public awareness of CTE, there’s still confusion and anger over how people suspected of having the brain disease are treated.

In the months before his death, Clark was suffering from depression, anxiety, sleeplessness and excessive fear, according to his wife, who said her husband was not seeing a therapist and was getting medication from a general practitioner rather than from a psychiatrist.

Lee Goldstein, a psychiatrist who works at the CTE Center at Boston University, said players who are as clearly symptomatic as Clark was should be working with a treatment team that includes a psychiatrist, a therapist, a social worker and regular supervision.

“This is something the NFL Players Association (NFLPA) should be all over and the NFL should be paying for,’’ Goldstein told USA TODAY Sports.

Allen Sills, the Chief Medical Officer for the NFL, said the league is funding CTE research, and working with the NFLPA to provide a network of resources, including mental health assistance.

“Greg Clark’s diagnosis underscores the urgent need for continued rigorous scientific research related to the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of traumatic brain injury, concussion and chronic traumatic encephalopathy,'' Sills said in a statement to USA TODAY Sports. "All of us who care for current and former athletes have more to learn about the acute and chronic manifestations of brain injury, and all clinicians hope that we will soon have better diagnostic and therapeutic options for our patients.

"We encourage current and former NFL players – and anyone else who may have brain health concerns – to seek help, prioritize their mental wellness and take advantage of mental health and brain injury resources."

The NFLPA did not respond to a request for comment.

But Clark’s story is about more than CTE research and science. It's also about how loved ones cope with loss.

“Most people that go through this, it’s like, ‘Eff football, eff the NFL, this is all their fault,’ ” Jayden Clark, Greg Clark’s oldest son, told USA TODAY Sports. “But I really don’t feel like that. I still love football.”

“Yep," Carie Clark interjected.

Her younger son does not play football, but Jayden Clark started playing when he was 8. “It’s a huge part of my life,’’ he said.

About three weeks after his father’s death, Jayden Clark resumed playing at Southern Utah. A middle linebacker, he suggested the game is just as risky as when his father played.

“I know people say, ‘Equipment’s changed, rules have changed,’ but that doesn’t make a difference, I don’t believe, at all,” he said. “Because I hit my head, I’m blacking out, seeing stars multiple times a game.

“But I think I needed to play, just to get through (his father’s death)."

Greg Clark was the oldest of eight siblings, including six brothers who played college football. One of them, Jon Clark, said he thinks most members of the family believe the focus should be on diagnosing and treating CTE rather than eliminating football or demonizing the NFL.

Carie Clark, 47, said she doesn’t want to alienate her family from the NFL, which she noted provides her with a monthly pension check. She also said she plans to renew her family’s 49ers season tickets.

"With my boys, that’s a real big thing for them, and I don’t want to lose that or feel like there's a disconnect,'' she said. "Greg was always looking for the positive. So in taking his lead, he wouldn’t want this to be just this all-out war with the NFL. Sure, they have some real problems. There's no question.''

Such as retired players suffering from CTE and in need of more help, she said.

"My biggest concern is there’s this group of guys that played at that same time (Greg Clark played) that are suffering immensely and scared," she said. "I know the NFL and the Players Association are trying really hard, but I just feel like we’ve got to find better ways to help these guys and (provide) places they can reach out.

"Because Greg, he wasn’t telling me. He was so scared. I've found lots of emails. He just didn’t want me to know because he was so worried that I was going to worry about him."

'A disease that smolders on'

Although Clark shot himself in the head, his brain was intact enough for study, said McKee, director of the CTE Center at Boston University.

Considering Clark played 14 years of tackle football and eight years of soccer, McKee said, she was not surprised by what she found.

Lesions on the frontal cortex and temporal cortex. Damage to the hippocampus. Evidence that the disease, which starts in the gray matter of the brain, had invaded the deeper structures involved in learning and memory.

MIKE JONES: If Colin Kaepernick wants back in NFL, USFL offers most realistic path to vindication

Greg Clark’s brain is one of more than 1,200 that have been donated to the CTE Center. About 350 of those brains belonged to former NFL players, and well over 90% of them were found to have evidence of CTE, according to McKee.

Approximately 35% of football players with CTE stage III and more than 93% of those with CTE stage IV develop dementia in their final years of life, according to a 2020 study from Boston University CTE Center. The average reported age of onset of cognitive impairment for someone with CTE is the early 50s.

By contrast, about half of Americans die with dementia, according to recent research. A study published in 2000 reported that approximately two out of three Americans experience some level of cognitive impairment at an average age of approximately 70 years.

“(CTE) is a disease that smolders on, even though they’ve given up football or whatever they were doing,” McKee said, adding that CTE likely contributed to Clark’s clinical symptoms of depression, anxiety, severe behavioral dysregulation, execution dysfunction and mild cognitive impairment.

None of this came as a surprise to Carie Clark.

Months before the diagnosis, Carie Clark became active with the Concussion Legacy Foundation, a non-profit group that conducts research into the causes and effects of brain injuries. Yet she has become equally focused on the role medication and other factors may have played in Greg Clark’s death.

In 2014, Carie Clark said, Greg Clark’s general practitioner prescribed Lexapro, a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) used to treat depression and generalized anxiety disorder. But the medication triggered suicidal thoughts and Greg Clark stopped taking it a week later, she said.

Greg Clark feared not only Lexapro but also that he might have CTE, Carie Clark said.

"In the early years of CTE research, some families did not suspect or understand CTE and were surprised by the findings after donating the brain of a loved one,’’ Chris Nowinski, the co-founder and CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, said by email. The CLF is a non-profit group that researches the causes and effects of injuries to the brain.

“But as research and awareness has grown, and now that more than 300 former NFL players have been diagnosed, families are recognizing that changes in a loved one who played football could be caused by CTE. Greg and Carie were concerned he had it and Greg sought treatment for symptoms he believed could be related to CTE.

“The problem facing families is that without a vetted criteria for doctors to apply to diagnose CTE in life, there are no studies of living CTE patients to inform what treatments work, don’t work, or make things worse. But more and more families are recognizing the symptoms and are seeking help, and clinicians are desperately trying to learn how to help these patients and families in real time.’’

Carie Clark said her husband underwent chelation therapy, designed to remove all metals from the bloodstream, and had his metal fillings, more than a dozen, replaced with non-metal fillings.

Greg Clark also attempted to address his lingering depression without medication, according to Carie Clark, who said her husband tried meditation, yoga, therapy and self-help books. But in 2021, his depression grew so severe that he talked to his general practitioner about the possibility of taking medication.

Greg Clark was prescribed Wellbutrin, an anti-depressant; Xanax, a sedative used to treat anxiety and panic disorder; and testosterone pellets, which are inserted above the upper hip with a small incision and, according to Carie Clark, in past years increased his energy and optimism.

But he continued to suffer, not only from depression and anxiety, but also from sleeplessness, irritability and excessive fear, said Carie Clark. She declined to identify the general practitioner but said she thinks the medication was mismanaged.

“I firmly believe he would still be here if it weren’t for those medications," she said.

David Reiss, a psychiatrist who works with the Concussion Legacy Foundation, said he could not comment specifically about Clark’s case. But he identified potential complications with the medications Clark was taking.

“It certainly would have been preferable to have a psychiatrist who had experience in this field,’’ Reiss said.

In treating someone with head injuries, Reiss said, he would have tried to “stay away’’ from the use of Xanax “because they’re already somewhat neurologically inhibited’’ and benzos like Xanax and valium can interfere with cognition.

Wellbutrin is better tolerated than Lexapro by people who have head injuries or “like living on the edge’’ because it has less of a flattening effect on mood, according to Reiss.

He said Wellbutrin could have posed a risk of triggering suicidality in Greg Clark.

The use of steroids should have been watched carefully because they can cause depression or get people “manicky and high.’’ Goldstein, the psychiatrist from the CTE Center, said the use of steroids was like “pouring on a little kerosene.’’

Greg Clark was an adrenaline junkie who enjoyed snow skiing, water skiing, wake boarding, boating, biking, hiking and, in general, consuming life with gusto – despite the onset of the brain disease.

McKee, the Boston University neurologist, cited the presence of “cognitive reserve.’’

“He was a highly intelligent person,’’ she said. “We know that people that excel occupationally, excel in their studies, educationally, that gives them the ability to withstand the pathology. That is, they can develop compensatory things, so that pathology’s not as obvious for someone who’s of high intelligence because they can sort of work around, find different pathways to get to the same end."

Greg Clark’s story shows that CTE does not operate alone.

Carie Clark traces the beginning of her husband’s descent to legislation in 2021 that threatened his real estate business. Then in early May, after contracting poison oak while mountain biking, he was prescribed an injection of prednisone followed by a 10-day course of oral medication.

His mood began to dip. More medication was prescribed. His work-related concerns deepened.

Suddenly Greg Clark was in a freefall.

Then there was the gun.

Carie Clark said her husband kept it locked in a bedroom closet after buying it more than a decade ago.

"Just for safety precautions,'' she said, adding that she had never even seen the gun until the coroner was carrying it out of her house.

She said she never could have imagined Greg Clark would shoot himself, but, in retrospect, that she can see the red flags. Like two nights before his death, she said, when Greg Clark told her, "I just feel like a burden. Sometimes I just feel like you're stuck with me.''

With the hope that the loss of a life might save others, Goldstein, the psychiatrist at the CTE Center, said Greg Clark’s story can help shed light on an important issue affecting former NFL players suspected of having CTE.

“I think about suicidality in these guys about the way I think about suicide in my dementing elderly patients,’’ Goldstein said. “When they still have enough wits about them, when they say they’re suicidal, they mean it.

“The sad and really tragic part of this is all of these (external factors), as difficult as they are, if they’re handled appropriately, they’re all preventable.’’

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Greg Clark, ex-NFL player who died by suicide, had CTE: 'So scared'