The first integrated basketball player, owner, has ties to Marlborough and Milford

Chris Boucher sought history. He found obscurity. His latest work may lead to renewed popularity.

The author from Lowell had published a pair of fiction books centered on youth basketball dubbed the “Pivot series” when his career took its own turning point. While reading a book about a Jewish team that played in the 1920s, Boucher made a connection: his grandfather emigrated from Quebec around that time.

Boucher discovered that a French-Canadian basketball team did form in his hometown of Lowell. More importantly, he unearthed a name that should have become synonymous with the likes of Jackie Robinson and Willie O’Ree.

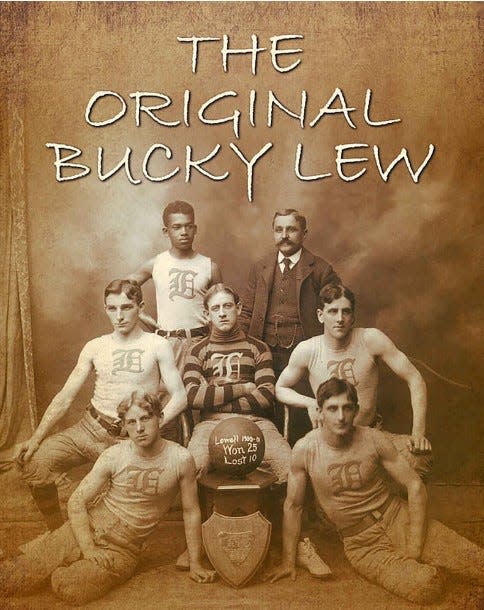

Harold “Bucky” Lew.

Lew, Boucher learned, not only played in the first integrated professional basketball game in 1902 in Marlborough, but his opening game as the first Black owner of an otherwise white league happened in Milford in 1915.

“I was shocked that I hadn’t heard of him,” said Boucher, who will appear at Tatnuck Bookseller in Westborough on Saturday from 12-1 p.m. to discuss and sign copies of his latest work, “The Original Bucky Lew: Basketball’s First Black Professional.”

The 203-page book published on May 1 is available on Amazon and tells the story of Lew’s transition from a cyclist to become the first Black professional player, coach, manager, head referee and owner – all happening well before Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton became the first Black player to sign NBA contract in 1950. (The NBA debuted one year earlier).

Due to Michael Jordan’s sale of his majority stake in the Charlotte Hornets last month, there are no majority Black owners in the NBA. And it wasn’t until 2002, when Robert Johnson paid a $300 million expansion fee for the Charlotte Bobcats, that the NBA had its initial Black principal owner of an NBA franchise.

As Boucher dug into Lew’s legacy, he knew he had his next project.

“I’ve been a basketball fan most of my life and I had never heard of Bucky Lew. I was obsessed with it; I found out as much as I could,” said Boucher, an instructional designer when he is not writing. “I saw that what he had done had been documented but never in a full-length biography, so I made that my goal. I just wanted to get it out there because I felt that he deserved it.

“It became a mission. This story deserved to be told.”

Boucher needed just nine months to perform research and write, with the help of Lew’s granddaughter, newspapers of the time, the Lowell YMCA and UMass Lowell’s Center for History. He already had a publisher – Wings Press – from his Pivot series, which further helped expedite the book's release.

Just saw #airmovie. Congrats to MJ for being the first to have an ownership stake in his shoes. Bucky Lew had to pay $4 for his kicks, but he deserves praise too for becoming the 1st Black owner of an integrated pro basketball team in 1915. pic.twitter.com/2iUH3Qp8Eu

— chris boucher (@iamChrisBoucher) May 17, 2023

He learned that Lew began as a cyclist, drawing inspiration from Worcester’s Major Taylor, who won a 1-mile sprint to become World Champion in 1899. Lew was eventually known as “Lowell’s Major Taylor” in his hometown.

But dribbling soon replaced pedaling. Lew signed with Lowell’s entry in the New England Basketball League, a recognized major league of its day. His games as a player drew up to 2,000 fans and his first night as a player/coach/owner attracted 1,700 fans to the Milford Armory. (For comparison, the Boston Braves baseball team drew 1,200 in their opening game in 1915.)

“It was big news in those days,” Boucher said. “That was a big crowd at that time.”

Lew did meet resistance, however. According to Boucher, a Hudson newspaper called him his owner’s “colored valet.” A New Hampshire hotel refused to allow him stay overnight, and when Lew arrived at a nearby train station to sleep, he was also rebuffed.

In another instance, the game’s best player, Harry Hough, led his team in a protest and they refused to play against him.

While he experienced racial trouble, he did have allies. Fans and teammates supported him as did the press, Boucher discovered. Papers throughout New England spoke glowingly of his remarkable demeanor and unique skill set. They dubbed him “The Original Bucky Lew” and reported “Lew is an attraction in every city where [he] plays.”

And when Lew was shooed away from that New Hampshire train station, his teammates walked with him 10 miles through a cold winter night to seek out a place to stay.

All this happened decades before Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain became the first Black stars of the NBA. Boucher’s book helps bring Lew’s ground-breaking achievements back to life.

“He was a well-known figure of his day,” Boucher said. “Obviously, he’s been forgotten since."

Tim Dumas is a multimedia journalist for the Daily News. He can be reached at tdumas@wickedlocal.com. Follow him on Twitter @TimDumas.

This article originally appeared on The Milford Daily News: Bucky Lew made basketball history in Milford, Marlborough