'Everybody benefits': Loveland teacher pushes for track and field expansion

Jim Vanatsky has been around track and field his entire life. He played football and ran track at Beavercreek High School before playing football at the University of Cincinnati.

After obtaining his master's degree in sports administration from Georgia Southern, he coached football and track in Florida before returning to Cincinnati. Most recently, Vanatsky was the head track coach at Loveland for 11 years before becoming an assistant at Moeller. He is also a world history and American government teacher at Loveland.

For the past decade, his background has led him to advocate for track and field expansion and a fair state championship.

Prep Baseball Report: State champ Moeller, Badin lead all-Ohio honorees

More: The Enquirer names 2023 Cincinnati High School Sports Awards nominees

How a Cincinnati coach got involved in the track expansion conversation

Vanatsky was Loveland's quarterbacks and receivers coach in 2013 when the Ohio High School Athletic Association expanded football from six divisions to seven. The Tigers had trouble competing with the larger Division I schools like Moeller, St. Xavier and Colerain. But in its first year in Division II, Loveland went 15-0 and won the state championship. La Salle won the next two Division II state titles with a combined record of 27-3.

As a track coach, Vanatsky began to see similar disparities. Since he is an Ohio Track and Cross Country Coaches Association (OTCCCA) district representative, he decided to do some research to see what expansion would look like for track and field.

"Even as a football coach, I saw the unfairness of the whole situation. I wasn't going to argue with it. We just went 15-0 and won a state title. But at the same time, I knew that from the track side and other sports side, this is inherently unfair," Vanatsky said.

Discussions within the coaches association were constant and came to a head in 2018 when they were instructed to propose an efficient two-day, four-division state championship. (The current three-division format is run with preliminary heats on Friday and championship heats on Saturday.) They did just that and recommended a two-year pilot for the new format to begin in 2020. That idea was shot down not by the OHSAA but by COVID-19.

The proposal was formally rejected in 2021. Even so, the OHSAA discusses expansion regularly and is currently having early-stage conversations about expanding.

“It’s brought up every year. There’s always a discussion about that,” OHSAA Executive Director Doug Ute said. “I think that having open discussions is always good.”

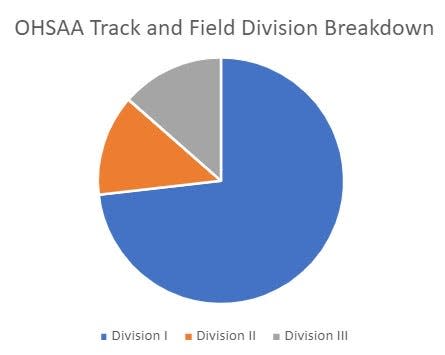

What the numbers say about the disparity in Division I enrollment

Vanatsky did not present the proposal to the OHSAA but he did spend countless hours researching facts and figures in support of his cause.

The OHSAA updated its competitive balance plan in 2019 after "school administrators raised concern about the disproportionate number of state championships won by non-public schools since non-public schools only make up roughly 16% of the OHSAA membership." This plan applied to football, volleyball, soccer, basketball, baseball and softball.

Vanatsky's issue was that the schools with higher enrollment numbers, public and non-public, consistently advanced to the state Final Four and won championships. From 2015-2018, every Division I state champion in boys and girls basketball and baseball came from a school that was in the top 10% of the state in enrollment.

In 2023, Southwest Ohio boasted nine of the 20 highest enrollments in the state for track and field. Those schools took 53 of 136 district girls' qualifying spots (39%) and 51 of 136 boys' spots (37.5%). At the state meet, six of the top 10 girls teams and seven of the top 10 boys teams were among the top 10% in enrollment.

Mason, which has a base enrollment of 2,551, took 35 combined spots from the district to the region and won the girls state runner-up trophy. Goshen, which has an enrollment of 667 and would benefit from expansion, sent one athlete to the regional meet.

Vanatsky also looked to other states for inspiration. Ohio is the seventh most populous state and is annually in the top five for boys and girls track and field participation. In the Buckeye State, track and field is the second-most populous boys sport behind football and the most populous girls sport. However, only about 4.3% of all participants make it to their respective state meet, a number that ranks 47th nationally.

"That's just lunacy," Vanatsky said.

Sixteen states with similar or smaller populations have five, six or seven divisions for track and field. Oregon, for example, has six divisions and holds a two-day state championship meet by running the championship heat of one event for multiple divisions before moving on to the next. This is not only more efficient but also gives athletes more time between events if they are participating in multiple finals, Vanatsky said.

"You don't have to reinvent the wheel here. We just have to be willing to go and find out how other people do it," Vanatsky said.

Here are possible models for OHSAA track and field expansion

Vanatsky came up with three models to try and achieve two goals: the largest school in a division should only be about twice as large as the smallest school in the same division (a 2:1 ratio), and each division should account for a minimum of 10% of the state's total enrollment. Currently, the largest school in Division I is almost five times as large as the smallest school in Division I.

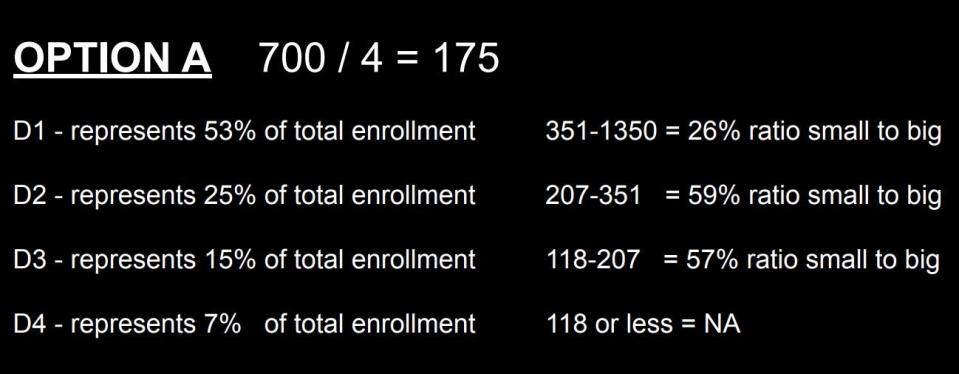

For the purpose of the models, Vanatsky used 700 schools.

Option A

This model puts an equal number of schools in each division, or 700÷4=175. While Division II and III achieve the ideal 2:1 ratio, the largest school in Division I would still be about four times as large as the smallest school. Additionally, Division IV would represent only 7% of the total enrollment. For these reasons, Vanatsky said this model is not feasible.

Option B

This model puts 70 schools, or 10% of the schools that field a track team, in Division I. The other three divisions would have an equal number of teams (630÷3=210).

The smallest schools in Division I and II would be just less than half the size of the largest schools, and the smallest school in Division III would be just more than half the size of their largest counterpart. Division IV is an outlier for the ratio since enrollment would range from 31 students to 138 students. However, Division IV would represent 10% of the total enrollment and satisfy the minimum requirement.

Option C

This model splits Division I into the 70 largest schools, and the remaining 157 schools that used to be in Division I would become Division II. Division III and IV would form from the old Division II and III and retain the same number of schools.

This would move even closer to the 2:1 ratio as Division I would be the only division where the smallest school is just less than half the size of the largest school. Even though Division IV would still be the smallest in terms of total enrollment, they would still make up 12% of the state's total enrollment.

The only reason this model could not work is the disparity in the number of schools in each division.

What is Vanatsky's recommendation to fix the problem?

Vanatsky believes Option B is the best because, in addition to meeting the two stated requirements, it also follows the football model of placing the 70 largest schools in Division I while having an even distribution among the other three divisions. Since the top 10% of the schools end up on the podium more often than not, this model would allow teams in Division II, III and IV to compete for championships more often.

"As long as it becomes a fair tournament, that's all I care about because then everybody benefits," Vanatsky said.

Regardless of how and if the OHSAA decides to expand track and field, Vanatsky hopes it is done correctly and sooner rather than later.

"My recommendation is the OHSAA take an aggressive posture on expansion," Vanatsky said.

What are the pros and cons of OHSAA track and field expansion?

The unspoken driving force behind the expansion is money. Track and field usually breaks even, meaning the money coming into the sport matches the total expenses. That trend would have to continue to do so if the expansion were to happen.

"The state doesn't want to just expand for the sake of expanding if they're going to lose money in the process," Vanatsky said.

There are several options to save money during expansion. At the district and regional level, Division I and II, and Division III and IV could piggyback their meets to save on facility, equipment and officiating costs. Another solution is to move the state meet from Jesse Owens Memorial Stadium at Ohio State University to nearby Ohio Wesleyan University (Ohio State charges about $70,000 to rent the stadium for two days).

The other issue is fairness for all athletes involved. Part of the OHSAA's mission statement is to "regulate and administer interscholastic athletic competition in a fair and equitable manner."

“The fundamental question is, is four divisions or the amount of divisions we have in a sport, is that where we need to be from a standpoint of fairness for student-athletes?” Ute said.

Should the OHSAA expand to four divisions, it is likely that one will get watered down and the competition won't be as fierce. But the ultimate goal is to ensure that the fastest times, best jumps and longest throws earn a spot in the state championship.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Loveland teacher Jim Vanatsky pushes for OHSAA track expansion