An eerie letter then a fatal trampling: Jack Trice was college football's greatest tragedy

In February for Black History Month, USA TODAY Sports is publishing the series “28 Black Stories in 28 Days.” We examine the issues, challenges and opportunities Black athletes and sports officials continue to face after the nation’s reckoning on race following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. This is the third installment of the series.

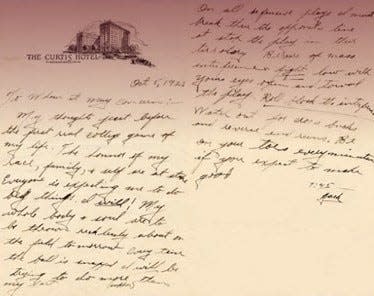

Alone inside a hotel room, segregated from his Iowa State football teammates, Jack Trice ate dinner in silence the night before the Minnesota game. As his teammates talked and laughed and plotted on-field strategy in rooms he wasn't allowed to be in, Trice took out a pen and crafted a letter on the Curtis Hotel stationery.

The words are eerie to read nearly 100 years after Trice wrote them in cursive, black ink, filling nearly two pages. The words were almost a foreshadowing, a devastating preview, of what would happen on the football field the next day.

Oct 5, 1923

To whom it may concern:

My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life. The honor of my race, family, & self are at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body & soul are to be thrown recklessly about on the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped I will be trying to do more than my part....

Trice was the first Black athlete at Iowa State in October 1923, a sophomore tackle at a time when virtually all college athletes were white. Black players weren't welcome at many stadiums, they often faced racial animosity on the field and, sometimes, much worse.

Inside his hotel room that night, there was no way Trice could have known what would happen the next day in Iowa State's game against Minnesota, his second of his college football career. But the words he wrote alone that night were uncanny.

It was almost as if Trice suspected the racially-motivated attack that was waiting for him the next day, almost as if he knew something terrible was looming.

Historians say Trice's letter wasn't intended for anyone else to read.

But the day after he died, the letter was found inside the pocket of Trice's coat. And that letter lives on forever as a missive to college football's greatest tragedy.

A brutal attack

In one of the first plays of the game between Iowa State and Minnesota at Northrop Field, Trice hurt his shoulder. It was later discovered a Minnesota player had broken his collarbone.

After the injury, Iowa State coach Sam Willaman asked Trice if he was OK. "And he says, 'Yeah, I'm fine. I'll keep playing,'" said sports historian Jaime Schultz. Trice went back out on the field.

"To the 11,000 spectators, Trice's (broken collarbone) seemed to have little effect on his play," the Northwestern Bulletin Appeal wrote of the game. "Time after time, he stopped the Minnesota plays directed at his position and tore open wide gaps in the Gophers' line to allow the Iowa backs to make gains."

Trice continued to dominate.

"And it wasn't enough," said Gary "Doc" Sailes, sports historian and performance consultant in "The Bright Path," a documentary on Johnny Bright, another player who was the target of a racially-motivated football attack. "So they stepped up the violence against this young man."

On a following play, Trice made a body block, throwing himself horizontally against an opponent and was knocked to the ground.

"And while he was on the ground, three guys went over to him and he was laying on his back and they were stomping him," said Sailes. "But then he rolled over to his side and they continue to stomp him."

Minnesota had finally done enough to take Trice out of the game.

"Because he was Black," Sailes said, "I have no doubt that influenced their strategy."

'And he was gone'

Even after the trampling, Trice wanted to go back into the game. Instead "against his wishes, he was taken to University Hospital where his condition was pronounced serious," the Minneapolis Star reported. Trice had sustained severe abdominal and intestinal injuries.

Remarkably, he was cleared by physicians to travel home with the team. A Des Moines physician was called to meet him at the station.

When the train arrived in Ames at 1 a.m., the physician realized just how dire Trice's condition was. Trice was rushed to the hospital.

Once there, doctors "declared the injured athlete's condition was such that an emergency surgical operation could do nothing for his relief," the Minneapolis Star reported. A surgery would have killed Trice immediately. Without surgery, he would also die.

"Trice sank rapidly until the end," the Minneapolis Star wrote. Trice's wife, Cora, was called to his bedside. Cora later recalled those final moments with her husband. "I said, 'Hello darling.' He looked at me but never responded."

"She hears the bell chime 3 o'clock. It's Oct. 8, 1923," said Schultz, "and he was gone."

Jack Trice was gone at the age of 21, two days after a football game that followed a letter Trice had written in silence, revealing that he knew this football game he was about to play was about much more than football.

"He wrote the letter (segregated alone in a room) to talk about his place," said Sailes. "And the thing about it, he knew his place. He wasn't comfortable with it, but those were the times."

On all defensive plays I must break thru the opponents line (and) stop the play in their territory. Beware of mass interference & fight low with your eyes open and toward the play. Roll block the interference. Watch out for cross bucks and reverse end runs. Be on your toes every minute if you expect to make good.

— Jack

After Trice died, the Des Moines Register wrote of the eminence of his words.

"Dead football star's letter written before game plans sacrifice," the headline read. It went on to say, "Jack Trice intended to use his body and soul recklessly for honor of his family and Negro race."

'A good man'

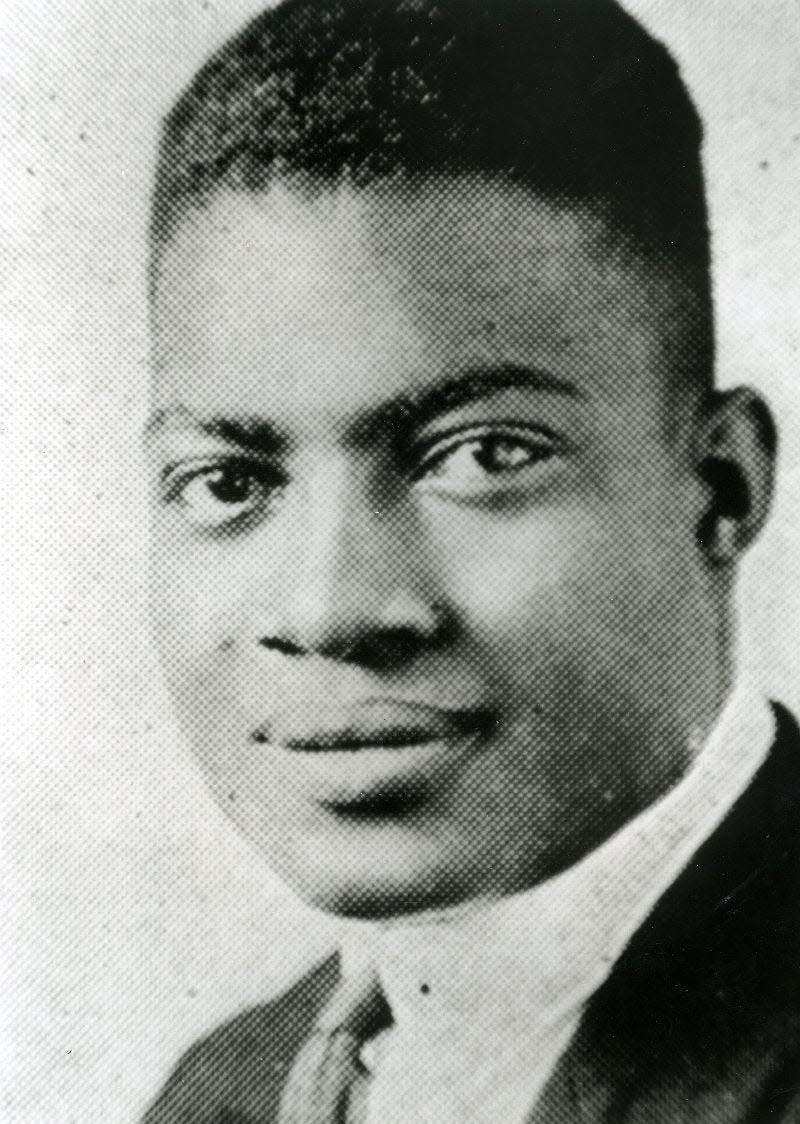

Trice was born in 1902 in Hiram, Ohio, the son of Green Trice, a former Buffalo Soldier, the nickname given to Black members of the U.S. Army.

He grew up loving sports and excelling at most of them. When he was 16, Trice's mother sent him to live with an uncle in Cleveland, where he played football at East Technical High. His coach there was Sam Willaman.

When Iowa State hired Willaman as football coach in 1922, he brought Trice and five of his teammates with him to Ames. The summer before his freshman year of college, Trice married Cora Mae Starland. She was 15 and he was 19.

At Iowa State, Trice and Cora both worked jobs to pay their way. Trice was also on the track team, played football and majored in animal husbandry, with plans to go south after graduation to help Black farmers.

Teammates described Trice as a quiet trailblazer, a man who loved his wife and an all-around star. In addition to being a standout football player that fall, Trice had won the shot putting event in the Missouri Valley Conference the spring before.

"He was popular among his fellow students and the professors," newspapers reported, "and was a fine student with his average grade a 90."

"A good man," teammates said, who walked off the field in 1923 wincing in pain and died two days later.

Players and coaches at Minnesota always contended the attack on Trice was not racially motivated.

"Members of the Minnesota squad were grief stricken when they received news of Jack Trice's death," the Minneapolis Star reported. Minnesota coach Bill Spaulding praised Trice as "a real football player."

"He was a hard hitter, a clean player and a thorough sportsman," Spaulding said. "Our boys commented after the game on his clean, hard play. He was in every play near him and stopped us more than once. He was a credit to the game."

Trice's letter lives on

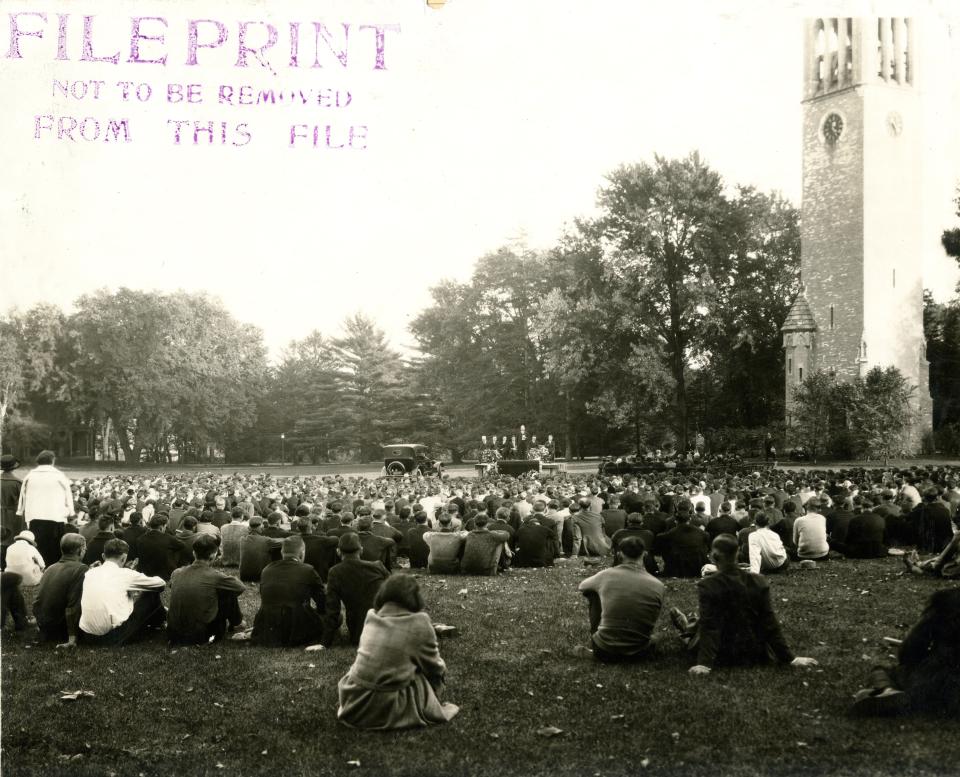

Their heads bowed, more than 4,000 Iowa State college students attended the memorial service held on campus for Trice the day after he died. University officials declared a "half holiday" so that students could attend.

"Jack Trice, Negro, a sophomore, winning his spurs in his first big college football game, spoke posthumously today to his fellows of Iowa State college and to athletes and true sportsmen throughout the land an athletic creed," the Des Moines Register reported of the funeral, "which will live long in the annals of his college."

The letter would live on.

"On the eve of the game at Minneapolis Saturday in which he received injuries that caused his death, Trice sat down the words of a letter," the Star wrote. "This letter, intended for no eyes but his own, was found in the pocket of his coat today."

And that letter was read by Iowa State's president as students and faculty cried, as they heard those eerie words that told a story of one man playing football for so much more than the game.

"All football players should know about (the Trice) story. It’s a significant story in college football, period, whether it’s today or tomorrow," GameDay analyst Desmond Howard said in 2020. "It’s one of the most significant — maybe the most significant."

In 1997, Iowa State's football stadium was named after Trice, a nod to a heroic player who sacrificed all for the game he loved.

“His story and the symbolic nature of the naming still conjures up emotions for me," Gene Smith, Iowa State’s athletic director in 1997, told the Des Moines Register in 2020. "Being a part of naming Jack Trice Stadium represents one of the most important experiences of my entire career."

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via e-mail: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Iowa State's Jack Trice's fatal on-field college football trampling