How the Eagles' first Super Bowl triumph changed Philadelphia

PHILADELPHIA – Fifteen years before the catharsis, there was silence.

Hollow, soul-sapping silence.

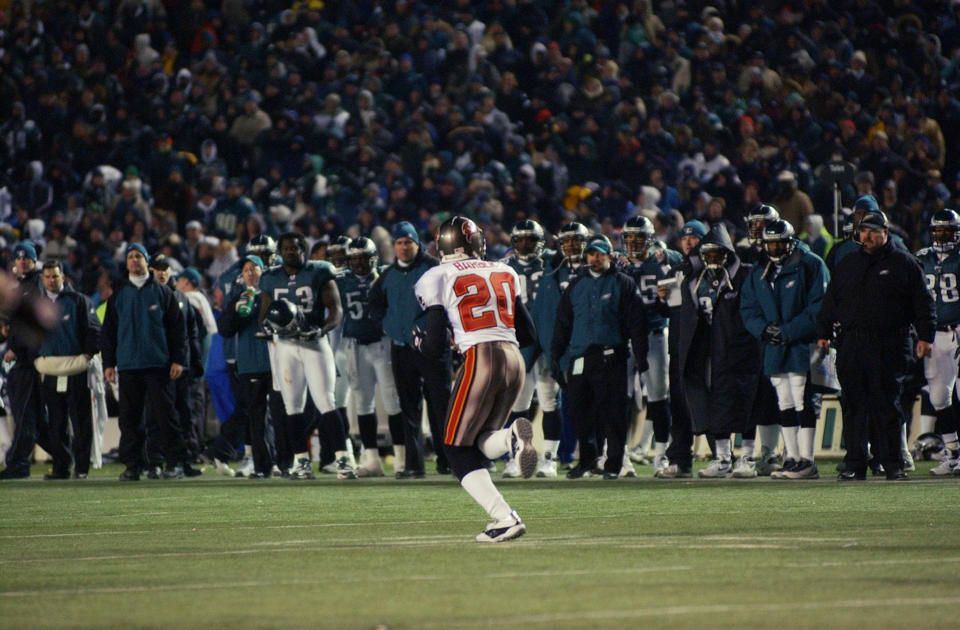

Ronde Barber was running. Galloping toward the Super Bowl, Veterans Stadium dynamite in hand. The Tampa Bay Buccaneers were about to upset the Philadelphia Eagles in the NFC title game. And for thousands, familiar doom was flooding back.

Ike Reese cried that night. Reese was a linebacker on that 2002 Eagles team, and still remembers the pain. But he also remembers decompressing back at home, flipping on the evening news. And he remembers the tears – his, but also fans’. He remembers their anger. Their raw emotion.

“I really felt there was a connection there,” Reese, now a sports radio host at 94WIP, says. “Because they felt what I felt.”

Reese had been in Philly since 1998. It wasn’t until that night that he truly understood. That he recognized the heartfelt fanaticism. For others, the realization hits earlier. Brian Dawkins was warned on his taxi ride in from the airport.

“And then I began to see for myself,” Dawkins says, “how passionate this fanbase is.”

Philadelphia is unique. Other cities care about sports. None has ever simultaneously cared so much and lost so often. The Eagles’ arduous Super Bowl-less odyssey embodied the plight.

That’s why the hypothetical Sunday night, with City Hall engulfed by euphoria, had become, as 24-year-old South Philadelphian Shamus Clancy says, “the most mythologized day in Philadelphia’s history.” It was the subject of dreams; of stuck-in-traffic mind wanders; of summertime chatter.

Clancy even penned a college paper about it. And he opened the final paragraph with a sentiment that was far from uncommon. “All I imagine as I twist and turn in bed,” he wrote, “is that all of our lives will undoubtedly miraculously improve the day the Eagles win the Super Bowl.”

As the myth crystalized last February, prophecies of a changed city proliferated. The morning after, prophecies became proclamations.

Yet on a sticky Wednesday morning seven months later, peeved Philly taxi drivers huff like always. Young professionals scurry down Market Street. Children chirp about “Fortnite.” High-schoolers put the shoddy finishing touches on homework. With the Eagles’ opener 36 hours away, the anxiety, for some, began to set in.

All of which begged the question: Has the Super Bowl genuinely transformed the town it taunted for so long?

***

To comprehend how Philadelphia has changed, one first must comprehend what Philadelphia is – or was.

Once upon a time, it was the birthplace of America, the most important city in the United States. Two centuries later, it was spiraling, its manufacturing might drained by an evolving world. Between 1950 and 2000, it lost more than a quarter of its population.

As residents fled and jobs evaporated, Philly’s reputation deteriorated. It was smaller than New York, unimportant compared to Washington, and in the shadow of both, unlike Chicago. It was the nation’s fifth-biggest city, the second-biggest on the East Coast, more than twice the size of the third. Yet it was rarely treated with corresponding respect.

All the while, its teams were losing. A lot. The Phillies became the first American sports club to 10,000 losses. Over the 50 years ending last December, among metropolitan areas with at least four major sports franchises, New York won 24 championships; Boston 19; Los Angeles 18; the Bay Area 17 and Chicago 12. Even Detroit claimed nine.

Philadelphia had five.

The losing became ingrained, a facet of the deteriorating reputation, but more importantly an ineradicable piece of self-identities. “We’ve always felt like the inferior, red-headed stepchild,” says Jason Myrtetus, a sports radio host at 97.5 The Fanatic. “The runt of the East Coast litter.”

Myrtetus mentions an “insecurity.” Eric “Erock” Emanuele, a diehard fan from New Jersey, talks about an “inferiority complex.” The city, Dawkins confirms, has a chip on its shoulder. It’s the “Philly vs. Everybody” slogan that screams off of T-shirts; the (under)dog masks that sold out hours after Lane Johnson and Chris Long first wore them; the song Jason Kelce introduced at the parade.

It had become so ingrained, so ineradicable, that when the city began to rebound last decade – art scene thriving, great restaurants popping up everywhere – perceptions didn’t change with it. Because the Eagles still didn’t have a Super Bowl. The void was inhibitive.

“You’re just hardened, and distrustful of things, because you’re always expecting the worst thing to happen,” says Clancy.

But as he nears the upshot, his mind drifting back to Feb. 4, his voice starts to break, weak with emotion.

“Finally, the best thing happened.”

***

Around 18 months before the greatest day of his life, Shamus Clancy couldn’t get out of bed. “I was either bitter and depressed, or drunk,” he says. “Those were my two states.”

He had, essentially, flunked out of the University of Pennsylvania. Failed classes, faked his graduation, lied to friends and family, a victim of his brain’s chemical makeup. He had battled depression before. Soon, the diagnosis would be bipolar disorder.

His life, in his own words, “sucked.” He knew he had to put it back together. He sought professional help. He was prescribed medication. And he made it to Lincoln Financial Field for the 2016 opener. He saw Carson Wentz lead a mechanical drive and float a pass to Jordan Matthews in the corner of the end zone. It was, Clancy immediately felt, “the first touchdown of the rest of my life.”

The Eagles gave him hope. Optimism. He hated his construction job. “I needed some sort of solace during my week to keep me going,” he says. Eagles podcasts and sports talk radio did the trick. They facilitated reveries, visions of that mythologized day.

And on Feb. 4, it transpired just as he had imagined it, “crowded into some South Philly basement with my dad and some friends.” Then out onto Broad, hugging childhood buddies, their only enduring bond the Eagle green one.

Nowadays, he’s “healthier, physically and mentally, than I’ve ever been in my life.” He re-enrolled at Penn and graduated in December. And like 1.6 million others, he’s a Super Bowl champion.

“After two-plus decades of disappointment, the Eagles started turning a leaf when I needed something to attach myself to,” he says. “Outside of meeting with a psychiatrist and a therapist, and going on some medications, they’ve been the biggest aid for me.”

***

The day after the Super Bowl, Clancy cooked up a tweet and hit send. It was funny, but innocuous – until he was DMing with Ashley Suder, whom he had never met, planning the re-creation of a famous World War II photo at the parade. By the end of the week, they were viral.

The Philadelphia Eagles Love Story, a three act play @suuderr pic.twitter.com/mxfaKXbY4o

— shamus (@shamus_clancy) February 8, 2018

Then there were TV interviews, one in studio. Then a Valentine’s Day date. Before either could comprehend the preposterous origin of their relationship, they were boyfriend and girlfriend. Last month, they moved in together.

You know, just in case you were still wondering whether the Super Bowl changed lives.

***

There were some tangible, quantifiable effects. The Eagles’ triumph was economic fuel. It influenced retailers and radio stations, beer companies and bars. Local newspaper subscription numbers soared. The city itself lapped up both tax revenue and free exposure.

“Every cut-in from a commercial, they would show the art museum or the Rocky statue,” notes Jeremy Jordan, a Temple University professor who has studied the subject. “To have 10 seconds highlighting Philadelphia in a positive way, what is that worth monetarily?” It’s possible, he says, “to put a value to that as advertising.”

But even Jordan knows that the true value is the intangible, the unquantifiable. It’s the everyday folk who used to write letters to Dawkins, pouring out their hearts, explaining how fractured households only united on football Sundays, and only stayed united when the Birds won. “Sunday,” Dawkins recalls, was the fan’s only chance “to share quality time with a male figure in their lives.”

Then there are people like Erock, whose friends joke that he was “born in a manger somewhere at a tailgate.” He’s third-generation. His maternal grandfather was a Franklin Field regular during the triumphant 1960 season; walked the ramps at the Vet while cancer ate away at him; climbed the stairs at the Linc until his body gave in. He had indoctrinated Erock’s mother. Erock’s father is on the Eagles’ drumline.

Erock had dared to dream, just like Clancy had. He had his own vision. But “the greatest part about that whole experience was the unexpected firsts,” he says. He bawled his eyes out upon spotting his dad at the parade. His grandfather never lived to see the day, but had his ashes scattered outside U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis. The following week, Erock says, “looking at my parents, feeling at ease because I don’t have to worry about them dying before they see a Super Bowl … What an unexpected relief that is.”

***

So has the Super Bowl fundamentally changed Philly? Down to the core?

There are, of course, countless Philadelphians who don’t care – even if they’re harder to find than ever before. For casual fans, life goes on. Some residents say people are happier; friendlier; less angry; more calm. Others say they notice no difference.

The fascinating question pertains to the invested fans. The ones who spent years bonding over heartbreak and disappointment. The ones who engraved the “Negadelphia” label. Eight months after columnists speculated that they were mired in the worst period in Philadelphia sports history, they’ve been gloating like few fanbases ever have.

In the spicy tweets and the smugness, some see an identity crisis. They see diehards confused, the source of their passion having been drained, the object of long-standing desire obtained. Free agency felt irrelevant. Draft hype was diminished. In the past, an embarrassing 5-0 preseason loss to the Cleveland Browns would have incited hysteria. But the fervor has dissipated.

“Just like when you’re dating,” Erock analogizes, “sometimes it’s all about the hunt.”

On the other hand, the insecurity, the shoulder chip … they haven’t disappeared. Even in the immediate Super Bowl aftermath, fans blasted national media personalities for hanging onto tiresome “snowballs at Santa Claus” narratives. Over 150,000 signed an anti-Cris Collinsworth petition, still fuming over what they perceived as Patriot bias on NBC’s broadcast.

The question, in a way, is unanswerable, because Nick Foles hasn’t yet thrown his first interception since Disney World; the Eagles haven’t yet faced a halftime deficit; fans haven’t yet had a dud of a performance to overreact to. Will they grumble and moan? Will they boo if Matt Ryan shreds the secondary? Will f-bombs fly if the Falcons romp Thursday night?

Nobody knows. And that’s the fun part.

“Just like there was BC and AD, for Eagles fans, there was pre-Super Bowl and post-Super Bowl,” Erock says. “Philadelphia will always be Philadelphia. But now we’re in a new Philadelphia.”

Henry Bushnell is a features writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell, and on Facebook.

Subscribe to The Yahoo Sports NFL Podcast

Apple Podcasts• Stitcher • Google Podcasts

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Trump: ‘Nike is getting absolutely killed’

• Bizarre out sums up Nats’ disappointing season

• Dan Wetzel: One big reason NFL ratings are way down

• 5 NFL coaches already sitting on the hot seat