Did UCF really provide the blueprint for beating Duke?

They were the five most intoxicating words of the NCAA tournament’s opening weekend. “The blueprint for beating Duke.” They stemmed from the Blue Devils’ second-round escape of UCF. And for 24 hours thereafter, amid chalk dust everywhere, they were unavoidable.

First came the takes. We pushed the “blueprint” narrative. Others did as well. Sure enough, in due course, the counter-takes arrived with equal force.

The debate, though, has been overly simplistic. The “blueprint” hasn’t even been defined or explained in detail. As the Blue Devils march into Washington, D.C., for a Sweet 16 matchup with Virginia Tech on Friday, it’s worth investigating what exactly UCF did that put it in position to nearly pull off the upset of the tournament, and whether it really is a roadmap for others.

To be considered a blueprint, three things must be true about the Knights’ approach. First of all, it – and not merely luck or streaky shooting – had to be a primary reason UCF came oh-so close. Second, it had to be novel – something that hadn’t already been piloted by ACC foes. And third, it has to be duplicable – in other words, not Tacko-dependent.

Why UCF’s Duke-stopping strategy was novel

The novelty of UCF’s strategy was degree and method, not philosophy or intent. Everybody knows Duke can’t shoot. Opponents have spent all season packing the paint. But UCF head coach Johnny Dawkins, a former Coach K pupil, took those tenets to extremes nobody else had dared entertain.

For much of the second half, Dawkins put his big man – either Tacko Fall or Chad Brown – on Duke’s jumpshot-lacking point guard – either Tre Jones or Jordan Goldwire. But the big was only “on” Jones or Goldwire in an Andrew Bogut-on-Tony Allen sense:

Jones is a 23 percent 3-point shooter. Goldwire has made three of his 25 attempts all season. Other coaches have conceded threes to them. None has so explicitly dared them. UCF guard Terrell Allen even seemed to be taunting Goldwire on one play:

This was an innovative ploy. It went beyond the norm. And it worked.

The numbers behind UCF’s Duke ‘blueprint’

Hold on, you might say. Duke shot 40 percent from deep. That’s its best shooting performance since early-February. How, then, did the strategy “work”?

Ah, but here’s where nuance matters. Duke did indeed make 10 of its 25 3-pointers. But eight of those 10 came from Zion Williamson, R.J. Barrett and Cam Reddish. (And five of those eight came in the first half.) Jones and Goldwire went a combined 2 for 11, with eight of the 11 attempts after halftime.

Dawkins went to the full version of the center-on-point guard scheme with a little over 15 minutes remaining in the second half – at the under-16 TV timeout, when Duke led 51-45, to be exact. In the first half, the Knights had alternated between a more traditional man-to-man and a zone. It yielded an eight-point deficit. But after intermission, UCF was plus-7. Duke’s half-by-half shooting splits tell the story:

We can break it down even further. Duke scored 1.13 points per possession over the full 40 minutes – again, a pretty good mark. But after the under-16, Duke’s first-shot halfcourt offense was dreadful. Excluding transition and second-chance points, it netted 14 points on 20 possessions. Duke’s season-long non-transition, first-shot effective field goal percentage is 48.0. Against Dawkins’ novel scheme, it was 38.2.

So, while there were other reasons UCF had Duke on the ropes – Aubrey Dawkins’ unconsciousness, Tacko Fall’s excellence – the second-half defense is really what allowed it to climb back into the game. It was plus-12 in the second half until the flubbed alley-oop led to Reddish’s clutch 3-pointer against a scrambling defense at the other end. When UCF wasn’t scrambling, it controlled the game.

Why UCF’s defensive ‘blueprint’ worked

Duke shot so poorly because its normally efficient offensive traffic patterns ran into roadblocks. The Blue Devils have the best 2-point offense in power-conference college basketball, making 57.9 percent of their attempts inside the arc. Their 3-point percentage, on the other hand, is 30.7, and 29.6 in conference play – the equivalents of 46.1 and 44.4 percent from 2-point range. As ESPN’s John Gasaway pointed out, that’s the biggest disparity of the KenPom era (since 2001).

Duke, therefore, needs to get to the rim – where it shoots 69.1 percent – to be the top-10 offense it is. But it couldn’t on Sunday because UCF essentially was playing Williamson, Barrett and Reddish 5-on-3. Ignoring Jones and either Goldwire (in small-ball lineups) or the offense-allergic big allowed the Knights to run an extra man at ball screens:

Sometimes 3-on-2 even became 3-on-1:

The middle of the floor was as congested as it’s ever been for Zion and Co. And Duke never really figured out how to unclog it.

The Duke blueprint is not Tacko-dependent

And it was not, to be clear, solely clogged by a certain 7-foot-6 center from Senegal. It certainly helps to have a dominant shot-blocker and shot-deterrent like Fall playing a one-man zone at the rim. But even when Fall was bench-ridden with foul trouble, and even before Johnny Dawkins stuck him on Jones, the Knights were ignoring Duke’s point guard. Look at the pillar of defenders Barrett stared down when he took a handoff from Javin DeLaurier at the top of the key:

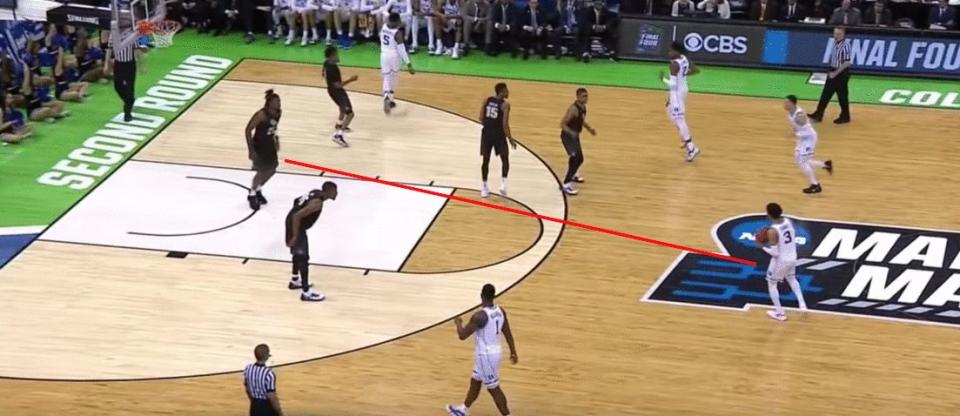

And look at how Allen left Jones completely alone on the weak side to disrupt a Barrett drive:

Tacko’s length made Barrett’s degree of difficulty high. But Allen – with a foot outside the lane ball-side while his man lurked 25 feet away – was the one who really disrupted the drive.

There’s absolutely no reason Virginia Tech or Michigan State can’t copy UCF’s strategy. It might not be quite as effective. But Duke will nonetheless have to adjust.

How should Duke adjust to the ‘blueprint’?

The first realistic non-adjustment to consider is to having Jones accept the challenge. Superficially, a Jones 3 is a 34.5-eFG% shot. But if Jones is wide open, with limitless time to compose himself, that number is probably higher. The question is how high. Can it be around 33 percent? The equivalent of a 50-percent 2-point look, better than that non-transition, first-shot effective field goal percentage we mentioned earlier?

If it’s close, a Jones three is a stomachable outcome. But if Jones can get it any time during a possession, it shouldn’t be the quick-trigger first option like it was here:

And, contrary to CBS-commentator belief, the solution absolutely is not for Jones to take one dribble in and pull a long 2. He’s a 37-percent mid-range shooter. That’s inefficient offense.

One thing Duke did do toward the end of Sunday’s game that proved fruitful, and could prove instructive, is toy with the matchup problems to which UCF’s scheme was susceptible. With a few screens, it could get Allen, UCF’s 6-foot-2 guard, switched onto Williamson. Zion going 1-on-2 and steamrolling into that clogged lane is still a high-percentage percentage play, despite the congestion:

From a defensive perspective, though, it’s a problem that can be addressed.

Coach K’s only drastic move would be to replace one of his non-shooters with Alex O’Connell – a one-dimensional, scrawny 6-foot-6 guard, but the team’s lone player who makes more than a third of his 3s.

O’Connell shoots 39.5 percent from beyond the arc. His playing time, though, has fluctuated wildly throughout the season – three minutes apiece against Auburn and Gonzaga at Maui, then eight straight outings in double figures, then six minutes, then 34, then five, then three, then 19, then nine. He didn’t play against UCF. He’d certainly space the floor and help solve the UCF-exposed conundrum. But K clearly doesn’t trust O’Connell as a decision-maker or defender.

So perhaps he’ll just confront the “blueprint” head on. Perhaps he’ll roll the ball out, tell his kids to go win four games. With their talent, they just might. And that’s the final thing to understand about the blueprint. It’s not foolproof. Adhere to it, and chances are you’re still going to lose. Chances are Jones will knock down enough of his threes, or a generational superstar will blast through your defensive roadblock, or Duke will win the game on the defensive end.

But the idea is not to guarantee victory. It’s a probabilistic play. And it’s an intriguing one, because the alternative has not worked. Only Gonzaga has beaten Duke at full-strength. Even in that game, an 89-87 thriller, the Blue Devils scored 1.21 points per possession. Even when this same Virginia Tech team upset Duke without Zion, the defeated Devils scored 1.14 PPP.

The blueprint, in conclusion, is about preventing Duke from doing what it has proven it can do successfully, and making it do something else. That “something else” might turn out to be even more lethal. But it also might be the source of a stunner. In March, against a national title favorite, that’s the type of risk you have to take.

– – – – – – –

Henry Bushnell is a features writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell, and on Facebook.

More from Yahoo Sports: