Colin Kaepernick triggered backlash but he also sparked awakening for many NFL players

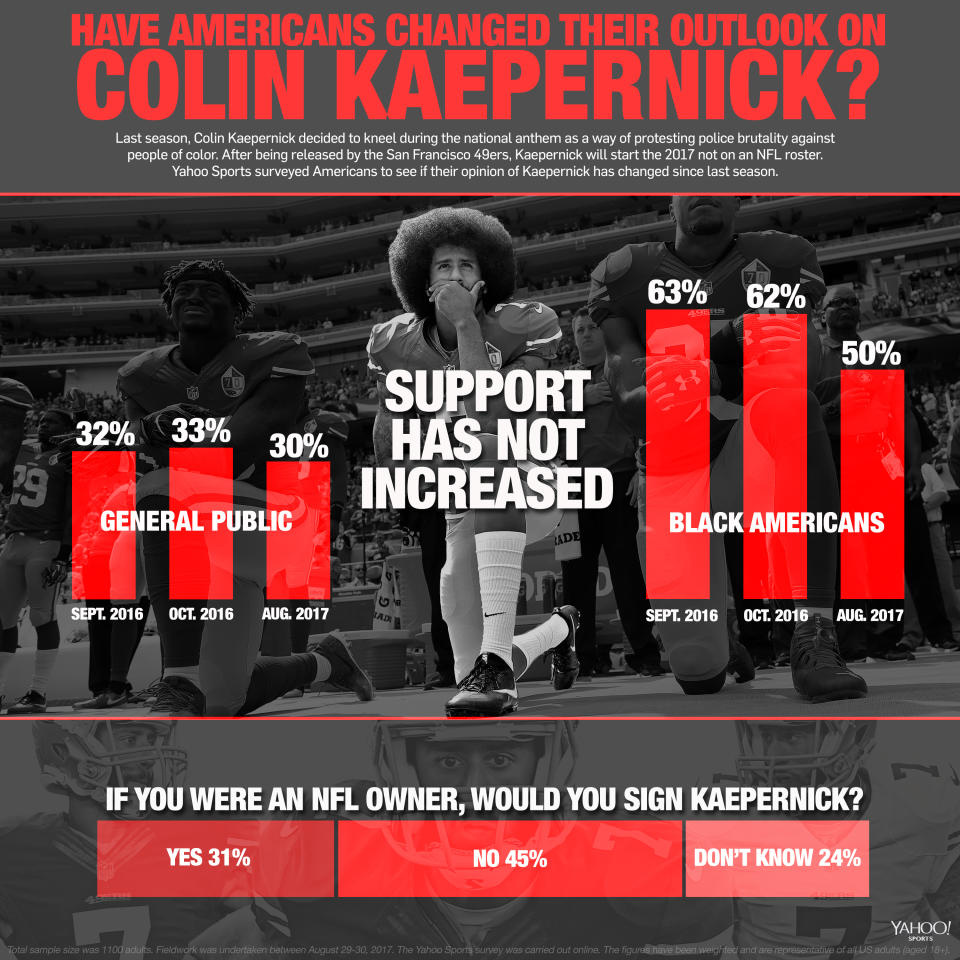

A year has passed since Colin Kaepernick first protested the national anthem. In one sense, his initiative has foundered: the quarterback is out of work and the intended discussion of police brutality and accountability has continually veered to a debate about the American flag and patriotism.

Just last weekend, the Cleveland police union boss who defended a police officer’s killing of 12-year-old Tamir Rice announced his group’s decision not to participate in a Week 1 pregame flag ceremony because some of the Browns kneeled during the anthem. It was a protest of a protest, and it pointed the finger back at the players instead of at the system Kaepernick is troubled by. The pressure boomeranged back to athletes instead of civic decision-makers.

It was something Kaepernick anticipated last August.

“I think there’s a lot of consequences that come along with this,” he told the media back then. “There’s a lot of people that don’t want to have this conversation, they’re scared they might lose their job or they might not get the endorsements, they might not be treated the same way. And those are things I’m prepared to handle and those are things that, you know, other people might not be ready for.”

That was prescient. A lot of people didn’t want to have this conversation. It’s possible, even likely, that the conversation scared would-be employers more than Kaepernick himself did. But the conversation is happening, and that’s significant.

****

More NFL players are protesting before games. Malcolm Jenkins of the Philadelphia Eagles is not only raising a fist during the anthem, he is also meeting with police leaders and making trips to Capitol Hill. When a white player for the Browns, Seth DeValve, took a knee before a recent preseason game, his African-American wife’s supportive response online went viral. “Colin Kaepernick bravely took a step and began a movement throughout the NFL,” Erica Harris DeValve wrote, “and he suffered a ridiculous amount of hate and threats and ultimately lost his life’s work in the sport he loves.”

Kaepernick’s detractors feel like sports should be a haven from all this. Sports are an escape from the “real world,” even though for most of us, the “real world” we’ve carved out is carefully cultivated: an escape from anything that challenges our worldview. Think about it: what percentage of your Facebook feed consists of friends who agree with you on pretty much everything?

By veering away from traditional avenues like Facebook, Kaepernick interjected in a lot of worlds. He pushed people (including media) to consider an issue they might not otherwise give thought to. And he tacitly challenged other football players to ask themselves if they should follow.

When Charlotte, North Carolina, became chaotic last fall after the police shooting of Keith Lamont Scott, some of the Carolina Panthers spoke up. “I feel like America has a problem,” Tre Boston said. “I don’t feel like America is a horrible place. I love America. … But at same time, there are wrongs that are happening every day.”

Thomas Davis called for peace and offered to be a liaison between police and protesters. The unrest abated in the days after the Panthers made their comments, in part because of the efforts of the National Guard and local clergy.

The team’s game that weekend went ahead despite fears of more turmoil. “I felt like it was important for me to step up and be one of the voices during that time,” Davis told Yahoo Sports last week, looking back. “I think it’s important. We are in the position. We have a huge voice. And it’s important to use that voice and do it in the right way.”

Davis has been a leader his entire career, and he says his social awareness comes from his upbringing in southern Georgia. “It was a combination of growing up with different friends of different races,” he says. “I grew up in a hometown that was partly divided. You had one group of one ethnicity on one side and another that that lived on another. When I went to college [at Georgia] it was all about one group coming together. That was a huge part of it.”

****

Football is one of the rare places in society that consistently blends race, faith, region and class. It promotes both individual leadership and team play. But it also conveys the message that every person is replaceable. There is a “next man up” mentality that keeps the system intact and also empowers the decision-makers over the employees. That’s part of what Kaepernick was alluding to when he mentioned “things other people might not be ready for.” There is a risk of lifelong consequences for a decision made in the two minutes during the national anthem.

Still, the comments from Davis and Boston last year reflect a little bit more readiness among older, more established players. Just this week, Cam Newton called the Kaepernick situation “unfair” and added, “Should he be on a roster? In my opinion, absolutely.”

Maybe an individual player’s decision isn’t to protest the anthem, but maybe, “What should I do?” leads to other, less controversial acts.

“We all have a role, as citizens,” Panthers safety Kurt Coleman said. “If we don’t as people come together, we will fall. Doesn’t matter what your profession is. If you have a bigger platform, stand on that platform.”

When asked if he wrestles with whether to speak up, Tampa Bay Bucs all-pro defensive tackle Gerald McCoy said, “I used to. I don’t now. I’m eight years in now. I feel I’ve done enough in this league where if I speak, my voice will be heard. I’ve done enough where if I do say something, people will listen.”

The Bucs held a team meeting during training camp in which players were encouraged to share thoughts or concerns they had about anthem protests. “[Head coach] Dirk [Koetter] let us have the floor,” said receiver Josh Huff, who has since been waived. “We said our opinions. You can’t be blind to the fact at what’s going on around the world.”

The players would not share what was said in a private meeting, but McCoy was open about his fears in a Yahoo Sports interview, worrying that a “civil war” is possible. “There’s just a rift, it’s a break, it’s a split in society,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be that way, but it is. That is a fact. Society is starting to split.”

This is not a radical opinion, especially after the tragedy of Charlottesville, Virginia. Football is a place where people come together, and it gathers huge audiences every week. Kaepernick’s protest is something that can be seen as divisive, but it also can be seen as something that was intended to include. And it has grown to include players Kaepernick didn’t even play with or against.

“I don’t see it as a distraction,” he said last August. “I think it’s something that can unify this team, it’s something that can unify this country. You know, if we have these real conversations that are uncomfortable for a lot of people. If we have these conversations, there’s a better understanding where both sides are coming from.”

For some, the conversation was never going to happen. For others, Kaepernick’s choice made the conversation easier. “Now that you look back at the season and what’s transpired since then, I think Colin Kaepernick’s decision to kneel or take a seat or to protest the national anthem was genius and worked better than I think he even probably assumed at first,” Jenkins told ESPN. “Because here we are a year later and it’s still a topic of conversation, and it sparked a conversation that’s been long-lasting. And since then, guys have really moved into action and have been doing a lot in the community.”

That conversation is happening more now than it has in the past. And it is happening even if Kaepernick is no longer playing.

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Dan Wetzel: The NFL makes a mess of the Ezekiel Elliott case

• Jeff Passan: Baseball’s long and confusing history with cheating

• These 32 NFL players are about to blow up this season

• Ray Lewis: Girlfriend’s ‘racist’ tweet cost Kaepernick a job