Blind in his right eye, Tommy Milton became first 2-time Indy 500 winner, died by suicide

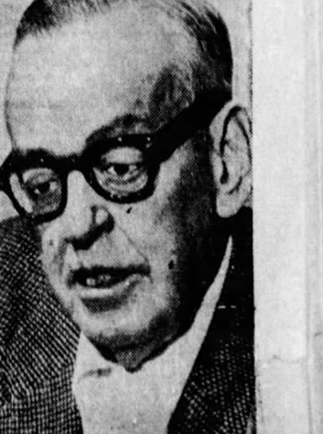

The .22-caliber pistol was found next to Tommy Milton's bed inside the Michigan mansion he shared with his brother. Police walked in on that hot summer day in 1962 and saw a racing legend slumped over in his bedroom with two bullet wounds to the chest.

After a pathologist performed an autopsy, sheriff's investigators were told that Milton's death "was definitely a suicide," the Indianapolis Star reported the day after Milton was found dead.

It was tragic, a horrific ending to the life of an underdog who had persevered and prevailed, a man the racing world called "the greatest driver of all time." Milton was the first two-time winner of the Indianapolis 500, in 1921 and 1923, and that was a remarkable feat in itself.

But even more remarkable was that Milton was 100% blind in his right eye and had a vision impairment in his left. Somehow, as he sped to two Indy 500 victories, Milton overcame an opponent that made skillful passing and sharp turns on the track terrifying. The only vision he had came from a bad left eye.

Milton's disability never deterred him. Along with two Indy 500 wins, he set nearly 100 records on race tracks all over the United States. He boasted 15 major victories in races more than 100 miles and he won the American Drivers' Championship for 1921, according to the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America.

After racing, Milton became a successful businessman, founding the Hercules Drop Forge Company and the Milton Engineering Company with his brother, Homer Milton. The $100,000 mansion the brothers lived in when Milton died would be worth more than $1 million today.

"Of all the successful American racing drivers in the first three decades of this century, there is one who stands almost alone for his level of achievement," Joe Freeman wrote in a Motorsports Hall of Fame story on Milton's 1998 induction. "He possessed a powerful sense of personal integrity, enormous courage and unbounded capacity for hard work. Tommy was able to post an incredible list of achievements."

And yet, with all his successes, Milton suffered from depression, brought on by his blindness and years of respiratory health problems that began as he raced. In later years, Milton had several heart attacks and, before his death, fought two serious bouts with pneumonia, according to IndyStar.

On the day of his death, as investigators gathered evidence and scrutinized Milton's house, they interviewed his brother. And what Homer Milton told investigators shocked them. He told police that he was not surprised at all that his brother had taken his life.

"Tommy had arranged his own funeral," Homer Milton told police, "for next Friday."

Forget your bad eyes

Milton was born November 14, 1893 in St. Paul, Minn., totally blind in his right eye and with a vision impairment in his left. He was born with a disability at a time when many children with his condition would have, at worst, been put in an institution and, at best, been allowed to live at home, probably not attending school and definitely not participating in sports.

But Milton had loving parents and a father who was a prosperous dairy owner, who told his son to forget his bad eyes and always remember that he could do anything he put his mind to. It didn't take long for Milton to become a standout athlete.

Of all the sports he played, Milton loved racing best. "It was an irresistible draw for Tom's fiercely competitive nature," Freeman wrote.

When he was 19, Milton took his family's old Mercer and spent two years on the county fair circuit as part of a traveling circus. Milton was eventually no longer welcome at the circus.

"Tom soon began to blow off the show's stars," Freeman writes, "an act of independence for which he was eventually fired."

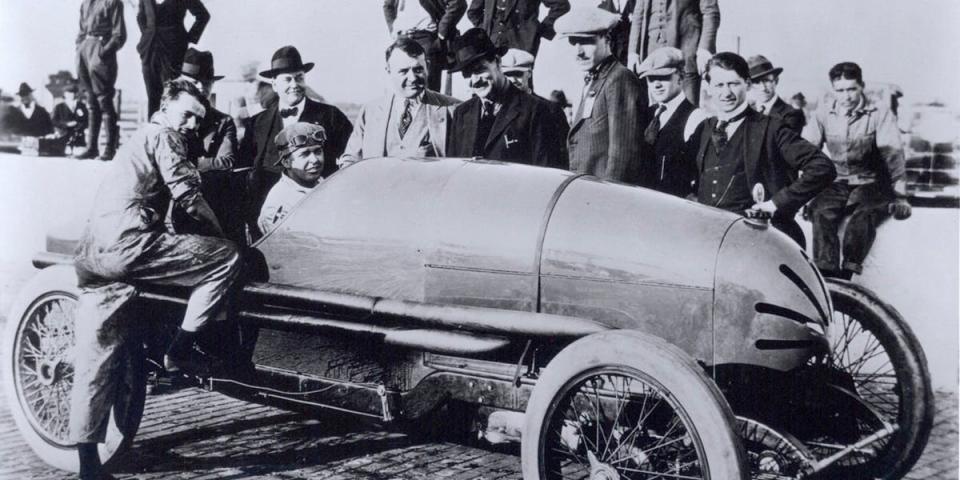

Milton found a new racing home with the team of Fred and Augie Duesenberg, where he raced his way to the Duesenbergs' top driver. In 1917, at 23 years old, Milton got his first big win in an intense 100-mile race in Providence, Rhode Island.

His racing accolades would only take off from there.

After building a radical twin-engine car, Milton broke Ralph DePalma's record with a speed of 156 mph at Daytona Beach in 1920. He took third place in the Indy 500 that same year.

Then Milton left the Duesenberg team. And a driver, who was blind in his right eye, won the Indy 500.

'Careful strategy and a clever ruse'

The 1921 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes Race, as it was called then, was a victory for Louis Chevrolet with Milton at the wheel of a new Frontenac straight-8. But the win was bittersweet for Chevrolet.

His brother, Gaston Chevrolet, had won the Indy 500 the year before and Gaston was supposed to be the driver racing that Frontenac to victory again, becoming the first two-time winner of the greatest spectacle in racing. But Gaston Chevrolet was killed when he crashed on lap 146 of a 200-lap race at the Beverly Hills Speedway in December 1920; it was the last race of the season.

When Chevrolet needed to fill Gaston's seat for the 1921 Indy 500, he turned to Milton, telling him he had faith he could win.

Milton had been working "to develop his own new machinery," after leaving the Duesenberg team, Freeman writes. But "he accepted a ride in a marginally competitive Frontenac for Indianapolis in 1921."

While the car wasn't a Duesenberg and probably shouldn't have won the race, Milton used "careful strategy and a clever ruse to fool race leader Roscoe Sarles," writes Freeman. "He came home the winner in America's most prestigious race."

At the halfway mark of the 1921 Indy 500, Ralph DePalma's Ballot led Milton by three laps. But on the 112th lap, a connecting rod dismantled, taking DePalma out of the race.

Milton maintained the lead until there were 50 laps left in the race, and Sarles began dueling with Milton for the front position. "With the Frontenac's 8-cylinder engine not performing well, the ever-thinking Tommy resorted to a bit of psychology," the IndyStar reported.

"In a burst of speed that put him directly in front of Sarles, Milton reached back and patted the tail of the laboring Frontenac," the IndyStar wrote. "The move so unnerved Sarles he refused to again take up the challenge, no matter what (his team owner) Fred Duesenberg did from the pits to get him to go faster."

Milton took the checkered flag two laps ahead of Sarles and celebrated in victory with Chevrolet. But as the cameras snapped photos of Milton, few people knew that the winner of the world's most prestigious race could barely see.

Today, Milton would not be allowed to race on the IndyCar circuit. The league's official rulebook states applicants "must successfully complete any IndyCar-prescribed physical and psychological examinations, which may include, without limitation, eye, neurological and substance abuse testing."

And yet in 1923, two years after Milton's first Indy 500 win, he raced to victory again. But this time he had a little help.

'He couldn't take it any longer'

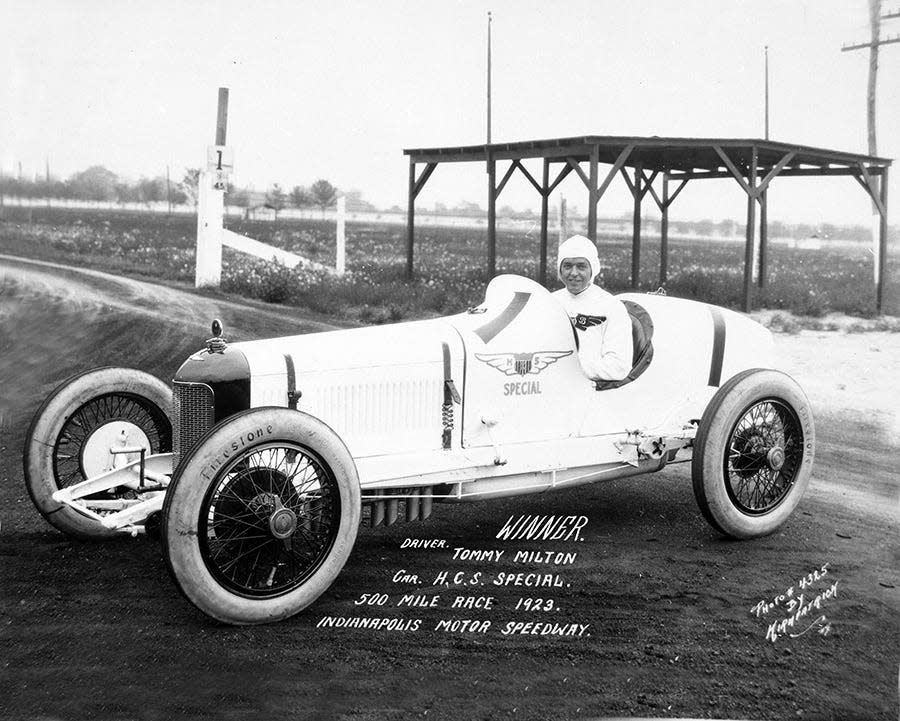

Before the 1923 Indy 500, Milton couldn't find his driving gloves. He searched the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, unsuccessfully, for a pair of gloves that would fit. Milton never found them, so he drove the first 200 miles of the race, gripping the wheel with bare hands and blisters set in, raw, unbearable blisters.

Milton couldn't race any further, at least for several laps. "He was relieved by another driver while (physicians wrapped) serious blisters on his hands," the IndyStar reported. After Milton's hands were bandaged, he took the wheel again behind his H.C.S. Miller.

And a 29-year old Milton raced to his second Indianapolis 500 victory.

After becoming a racing hero, Milton drove three more years. He officially retired in 1926 after the Fulford 300-mile race and then landed an executive position at Packard Motor Company. As an engineer, he designed and developed the only front-wheel drive car the Packard Company ever made.

"During his later years as an engineer for Packard, Milton was invited to drive the Packard pace car at Indianapolis in 1936 and agreed with the suggestion that the car should be presented to the winning driver after the race," according to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum. "That tradition, with some slight modifications, continues today."

Milton became a successful businessman, rich enough to live in a ritzy mansion, and he served as Chief Steward for the Indy 500 from 1949 to 1952, an annual celebrity at the race for years.

But then Milton started battling serious health issues and "he couldn't take it any longer," the IndyStar reported.

When Milton died by suicide in 1962 at the age of 68, newspapers reported that "the greatest race driver of all time," who was blind in one eye, the underdog who had prevailed, had taken his own life. And the racing world mourned.

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Blind in his right eye Tommy Milton was first two-time Indy 500 winner