The age of Trump seems like a better time than ever for an XFL revival

Calls for a safer, more regulated NFL have been concurrent with the rumored revival of Vince McMahon’s XFL. Which couldn’t make more sense

During an interception return in the third quarter of last week’s game between the Carolina Panthers and the Green Bay Packers, Panthers cornerback Thomas Davis appeared to relish the rare opportunity to play the role of lead blocker. Davis saw Packers wide receiver Davante Adams following the play unaware and launched his shoulder into Adams’s helmet. Davis was laid out onto the ground and suffered a concussion, forcing him from the game and potentially costing Adams his ability to participate in the rest of the season.

Davis received a two-game suspension for the hit, meaning he is done for the remainder of the regular season. But this collision and other violent, over-the-top hits to the head like the one that left Tampa Bay quarterback Tom Savage shaking on the turf two Sundays ago have led some football pontificators to suggest the NFL needs to adopt a targeting rule akin to the one currently on the NCAA books, which would allow referees to eject players for overly violent hits to a defenseless player’s head. NFL executive vice president of football operations Troy Vincent said on 6 December of a targeting rule, “I think it’s something that we have to consider.”

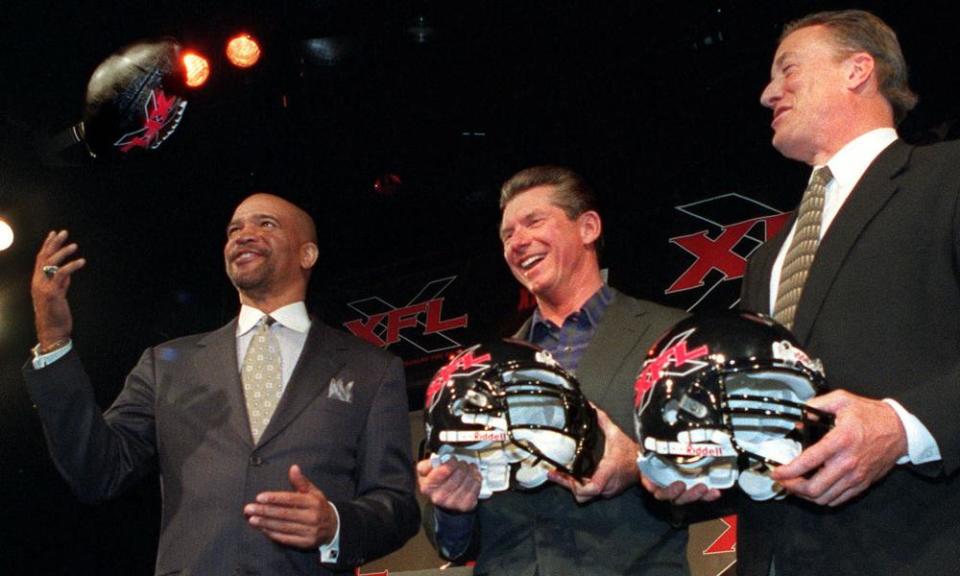

Contrast this news with a rumor to surface of late: the XFL, Vince McMahon’s ill-fated wrestling inspired spring football league, may be up for a reboot. According to Deadspin’s David Bixenspan, McMahon has created a new venture called Alpha Entertainment that will “explore investment opportunities across the sports and entertainment landscapes, including professional football.” Alpha has filed for trademarks on “URFL” and “UrFL”, and another McMahon venture, VKM Ventures LLC, applied to trademark “For the Love of Football”, “UFL”, and “United Football League”. These applications have all been filed since September, leading some to speculate the XFL revival whatever name it ends up with – could be a response to the disgruntlement some NFL fans have expressed in the wake of player protests against police brutality.

There is no doubt in my mind that McMahon would jump at an opportunity to capture the disgruntled flag-waving sect of NFL fandom. But to me, what makes the idea of the XFL appealing today is its active celebration of football’s most violent moments. One XFL advertisement featured “passing drills” in which the receivers caught footballs shot out of a tank cannon, an obstacle course in which running backs ran over landmines, and the promise of one of the XFL’s signature rule changes: no fair catches, as the poor punt returner was slammed to the ground by a wrecking ball.

Another XFL promotion promised “No indoor fields, no prima donnas, no wimps. Here, the rules are fiercer, the clock is faster, and halftime is a break, not a vacation. This is football, the way it was meant to be played.” This commercial concludes with the same promise of no fair catches, as a punt returner is slammed to the turf, not this time by a wrecking ball, but by three opposing players who knock him clear into the air before driving him to the ground.

It should come as no surprise given its creator’s origins in professional wrestling, but the XFL was more than willing to sell the brutality of the game. That used to be true of the NFL more recently than some would like to admit. The NFL has marketed video collections of its biggest and most destructive hits, titles ranging from 1968’s “Bone Crushers” to 1991’s “Thunder and Destruction”. The NFL was fully aware that many fans weren’t tuning in despite the violence, they were tuning in for it, and the league was happy to market these explosive and dangerous hits to keep these fans coming back to their TV sets every Sunday.

It has been clear to the league for some time, though, that continuing to market jarring hits to the head to fans -- including the youth football players who are one of the major target demographics for those films -- is an untenable position in the face of the concussion and CTE crisis. Thus have the Bone Crushers tapes been replaced by the era of Heads Up Football, and thus has the NFL gone from marketing these hits as recently as two decades ago to suspending players over them in 2017.

“You used to see these tackles, and it was incredible to watch,” then-presidential candidate Donald Trump said at a rally in Reno, Nevada last January. “Now they tackle—’Oh, head-on-head collision, 15 yard’ – the whole game is all screwed up. You say, ‘Wow, what a tackle.’ Bing. Flag.” He finished up his rant on football by saying, “Football’s become soft. Football has become soft. Football has become soft like our country has become soft,” drawing applause from the roughly 3,000 attendees.

There is absolutely an audience for this kind of an attitude towards football and its violence. McMahon – who has given Trump a role on WWE shows in the past and whose wife Linda is a part of Trump’s team as Administrator of the Small Business Administration – no doubt sees this. The first iteration of the XFL made many mistakes, but there was enthusiasm for spring football and the specific kind of environment the XFL was trying to create. Opening Day brought an atmosphere of surprising excitement to XFL stadiums, many of which didn’t even bother to open their upper decks thinking they wouldn’t draw that kind of interest. Tom Veit, general manager of the Orlando Rage, recalls the frenzy at the Citrus Bowl. “We ran out of beer. The beer distributor ran out of beer and had to start shuttling beer in. I think the building holds 64,000. We had 36,000. At 36,000, we set the beer record. We’re pretty proud of that.”

At the heart of the rise of Trumpism and the ideology of Making America Great Again is this idea that America has gone soft. Perhaps the Bush years, as the NFL ramped up the militarism in the wake of 9/11, weren’t the best time for a challenger to the NFL to seize upon its softness. What’s different now? The NFL is constantly under the microscope since the concussion crisis blew up. Even if new CTE findings don’t blow up the league’s $1bn concussion settlement, the league has to ask itself how to maintain its mass marketability and player pipeline as the risks and consequences of football become clearer and clearer. If the NFL had any desire to clamp down on hits to the head like the one that ended Adams’s day Sunday, it would have done it years ago. Their response, from suspensions to the consideration of a targeting rule, is all about protecting the NFL shield from litigation and a public relations nightmare.

As such, now seems like a better time than ever for an XFL revival. As much as the NFL might be loath to admit it now, hits like the one Thomas Davis delivered on Davante Adams last Sunday are the reason many tune in every Sunday. The URFL, UrFL, XFL 2, or whatever it ends up being called won’t have the broad reach the NFL brings, but there very well might be a space in this market to appeal to the same kind of people who cheered when Donald Trump decried football’s softness during his campaign. Those people have always formed a substantial piece of the NFL’s fanbase, and if the NFL can no longer cater to them, someone like Vince McMahon will happily step in and fill that void.