New 1997 Michigan football book remembers how THAT hit vs. Penn State epitomized title run

On Nov. 8, 1997, for the first time in 26 years, four the country’s top five teams faced off against each other on the same day. No. 4 Michigan (8-0) at No. 2 Penn State (7-0), the first Big Ten bout of unbeatens in November since the famed 10-10 tie between Michigan and Ohio State in 1973.

Entering ‘97, Michigan football had suffered four straight four-loss seasons and third-year head coach Lloyd Carr lived firmly on the hot seat. “Judgement Day,” a nod to the 1991 blockbuster “Terminator 2,” would either see U-M shed its “Mediocre Michigan” label or live up to it — in crushing fashion — one more time.

The resulting performance — a truly dominant 34-8 Wolverine thrashing — would be one of the most important in Michigan football history.

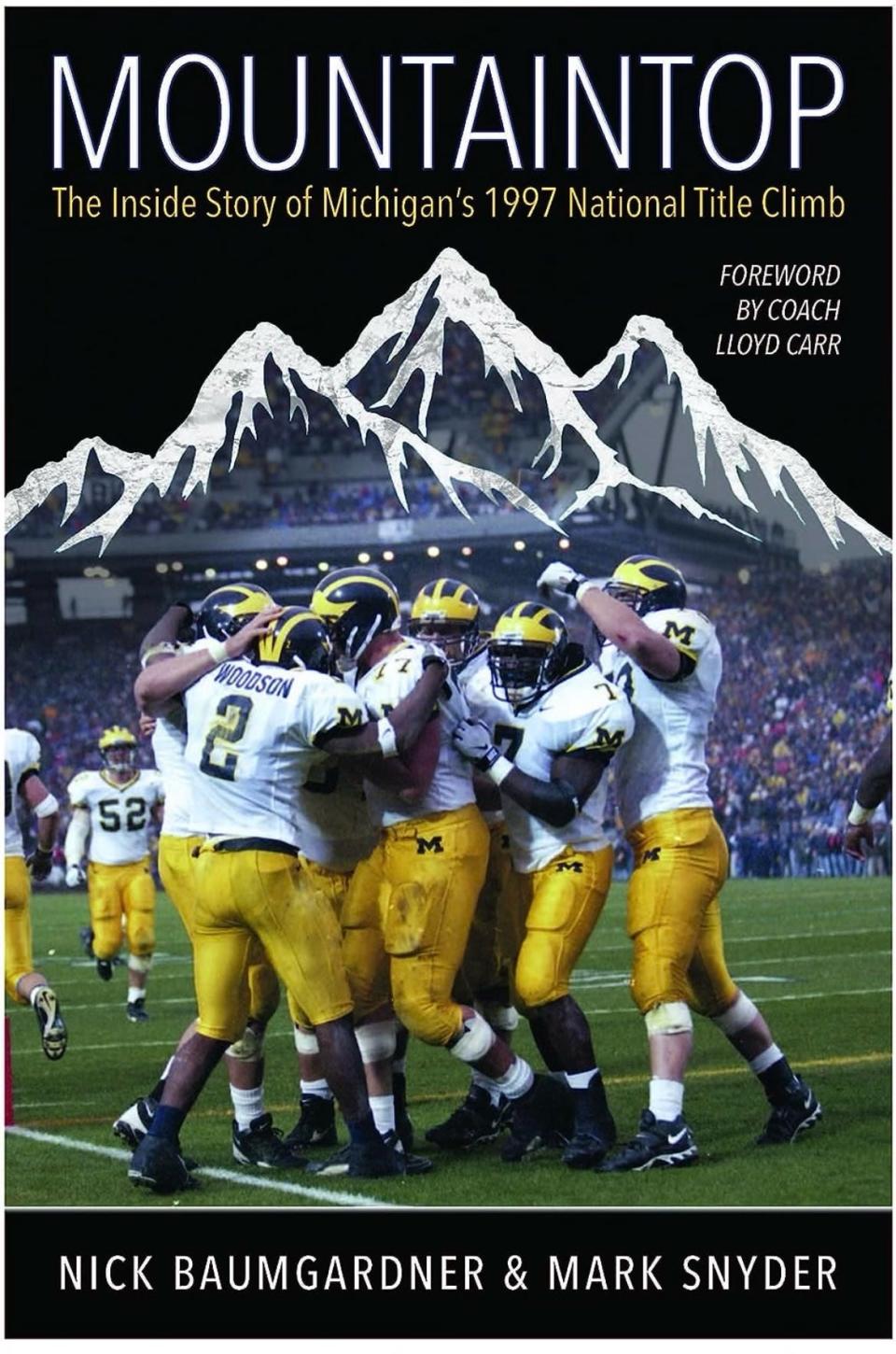

A new book, “Mountaintop: The Inside Story of Michigan’s 1997 National Title Climb,” written by former Free Press Michigan beat writers Nick Baumgardner and Mark Snyder, relives the season that featured one of the most fierce defenses in college football history and even included a backup quarterback named Tom Brady. The book is now available for purchase at Michigan1997Book.com. Here's an excerpt from the first chapter of the book:

Judgment Day at State College was no ordinary game. So Marcus Ray delivered an extraordinary pregame rant.

THIS YEAR'S TEAM: Michigan captains reflect on high honor: 'Biggest accomplishment of my life'

A renegade of a safety from, of all places, Columbus, Ohio, Ray had grown into the on-field voice of the country’s top-ranked defense. That defense, already lauded by Iowa coach Hayden Fry as the best he had seen in years, had yet to allow a second-half touchdown. Ray put the bull’s-eye on Penn State tailback Curtis Enis, a 240-pound junior sensation with Heisman steam who had rushed for 211 yards against Ohio State.

“We are not tackling Curtis Enis below the waist,” Ray barked to the meeting room. “If we tattoo his ass, he will quit.”

Ray’s audience included secondary coach Vance Bedford — a savvy 39-year-old assistant who knew when to let Ray’s speeches go and when to cut them off. This one, he figured, would be fine.

“I don’t care who you are,” Ray bellowed. “I don’t care how much you weigh. Do not go low. If you hit his ass, the rest of us are coming and we will treat this like a heavyweight fight.”

Ray was a cerebral hitman whom his teammates decades later still called the smartest defensive back they played with. He idolized Deion Sanders, a flashy cornerback at Florida State and NFL star, and Ray never forgot anything. He remembered Enis from high school.

Enis was a running back at Mississinawa Valley in western Ohio and Ray a linebacker at Eastmoor Academy in Columbus. Ray knew Enis was a great physical talent with quick feet. Ray also knew, thanks to squaring off with him in a prep all-star game, that Enis didn’t like to be tested physically all game long.

The rest of the defensive backs room — which included All-America cornerback Charles Woodson and two safeties who rotated with Ray, Daydrion Taylor and Tommy Hendricks — was in full agreement. These players, Ray and Woodson specifically, were key contributors in 1996 and saw every crack in Michigan’s foundation. They also knew how to fix them. Against Penn State, no one in Bedford’s room was going to leave anything to chance. The pact was on.

Until it wasn’t.

On Enis’ second carry, with Penn State already trailing 10-0 and facing a second-and-20, the Nittany Lions ran a draw play and Taylor broke the pact.

In his third year out of Texas, Taylor arrived in 1995 as part of one of the most talented recruiting classes in U-M history, and he proudly wore the badge — alongside Ray — as a headhunter. Soft and reserved away from the field, Taylor could be found hanging out with Woodson and cornerback Brent Washington or keeping to himself. On the field, however, Taylor was a pit bull who prided himself on physicality.

When Enis cut to the outside, Taylor went at his ankles. Enis, who would finish fifth in the Heisman Trophy voting, sidestepped Taylor for a 14-yard gain, Penn State’s first productive play of the game. But Michigan got a stop on the next play and forced a punt.

MORE OF A LOOK BACK: 1997 Michigan Wolverines football: Relive the historic championship run

With two minutes left in the first quarter, Michigan was dominating the game. The Wolverines had entered Beaver Stadium intent on proving that they were not only capable of beating the country’s No. 2 team on its home field — but that they could do so in dominant fashion. Even if the majority of U-M’s fan base was anticipating an inevitable implosion. The players had spent 11 months talking about how sick and tired they were of being sick and tired. Sick of falling short in the crucial moments. Tired of feeling like they were less-than in their backyard. This afternoon, Michigan knew, was a chance to change everything. It was, in so many ways, the chance.

And Ray was livid.

He jogged to the sideline, picked up the press box phone, dialed Bedford and told him — loud enough for Taylor and everyone else nearby to hear — that Taylor, per the rules of the pact, was out and Hendricks, who rotated with Taylor, was in. Bedford reminded Ray who was the coach and told Ray to go support his teammates.

Defensive coordinator Jim Herrmann wasn’t so kind. He saw the game the same way Ray did. And unlike Ray, Herrmann was a coach. When Taylor got to the sideline, Herrmann let him have it — in front of everyone.

Woodson and the rest of the defensive backs did what they always did: They put their arms around Taylor’s shoulders, pushed his chin toward the sky, and told him the same thing they always told each other: “Next time, run him over.”

*****

Then, out of nowhere, it came: CRACK!

It was the loudest hit that almost everyone near the field had witnessed. Before or after.

On the final play of the quarter, Penn State tight end Bob Stephenson leaked out of the backfield from a fullback position, caught a dump-off pass, and turned upfield into open space along the sideline. Before the series, Taylor said decades later, he remembered standing on the sideline thinking only of the message he and his teammates wanted to send the world. As Stephenson picked up the Nittany Lions’ initial first down, Taylor came screaming across the field and drove his helmet through Stephenson’s chest.

The hit ended each player’s career.

Bedford heard the hit from his seat in the press box. The crowd of 97,498 sat in silence as the players didn’t move. Woodson stood over Taylor.

Taylor and Stephenson — who suffered a severe concussion, among other injuries — were knocked out. When Taylor’s head cleared, he looked up and told Woodson he could not feel his legs. Woodson was so rattled that he considered quitting on the spot. “I’m like done,” he recalled thinking. “I don’t even want to play football anymore. ... You can take me back to Ann Arbor right now.”

But Taylor eventually was able to walk off the field — and well enough that assistant coaches began wondering whether he could be available for the second half. Upon further examination on the sideline, though, Taylor was taken to a nearby hospital for X-rays that didn’t find much. He flew home with the team that evening before heading to the University of Michigan Hospital for additional tests.

The next time his teammates saw him, he was in a medical halo designed to stabilize his neck.

“That was tough,” Woodson recalled. “To see him in that state ... it just makes your whole body weak.”

But Taylor had sent his message on the field.

“After Daydrion’s hit, you could just sense it,” linebacker Chris Singletary said years later. “The look in their eyes. It was, ‘Uh-oh! We’re not built for this.’”

Taylor has recalled his violent tackle more times than he can count. It has come to define his life, because it was the moment that forced him to change it. He can remember the stinging pain as a doctor he had met only minutes earlier told him that his football career had ended and that he needed disks fused in his neck. Then the doctor twisted a screwdriver that drove screws through Taylor’s skin and into his skull. But Taylor said he didn’t feel pain once metal tore into bone, only pressure.

Like his head was caving in on him.

However, Taylor — who walks and talks and lives a happy life with family and friends to this day in Texas — recalls the hit without hesitation or regret, even though he had the potential to reach the NFL. He recalls it with clear eyes, and while he doesn’t recall every detail of the play, he remembers exactly what his mindset was when he stepped onto the field seconds before delivering the hit.

“We were there to show everybody who we were,” Taylor said. “We needed to send everybody a message. Everyone’s focus and mentality and thought process that day was simple: it’s time to show the world. We’re going to show the world, show Penn State. They thought they had a chance. They do not know who they’re about to run into. And Penn State is going to learn today.

“We knew what they were; we knew we were going into their home stadium; we knew they were a good football team. But they hadn’t seen what we were about to bring. We weren’t just going to let them know, either; we were going there to put everybody on notice.”

Statement received.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: New 1997 Michigan football book remembers THAT hit vs. Penn State