10 years later, Ohio State's Marcus Hall embraces his viral double bird at Michigan

Marcus Hall fumed.

The words devastated him. It was Nov. 30, 2013, and mere seconds earlier Hall listened to a referee announce his ejection from the 110th edition of The Game for his involvement in a melee.

As the Michigan Stadium crowd roared, he felt his body turn hot on the sideline. Hall ripped off his helmet and slammed it to the ground.

Before anyone attempted to console him, Hall kicked a bench. He shook his fist.

Ohio State football: Michigan week is here. Here's what we know about 'The Game'

“I was all over the place,” he said.

His emotions spiraled as he confronted a brutal reality. A senior Ohio State offensive lineman, he would never again appear in one of college football’s biggest rivalries. It felt incomprehensible.

As he stomped toward the stadium’s midfield tunnel, he glanced into the stands, raised both arms and extended his middle fingers.

“I never had the intention of flipping a hundred thousand people off,” Hall said, “but when you kick me out of that game and I’m left with nothing but a ball of energy, that’s what happened.”

His double-bird salute went viral in a flash, captured on ABC’s telecast in front of millions. Viewers snapped screenshots. They made GIFs and memes.

Hall saw one as he sat in the visiting locker room during the Buckeyes’ 42-41 win. Someone sent him a photo in which his torso was cropped onto a roller coaster cart, his hands in the air like he was prepared for a drop on the track. He found it strange, goofy. His phone continued to light up.

The aftermath was a whirlwind. While flipping off a sea of maize and blue made him an instant cult hero among Buckeyes fans who reveled in the display of animosity, others considered it classless. He issued an apology and was reprimanded by the Big Ten. Ohio State suspended him.

Ohio State football: Are Buckeyes expected to beat Michigan? Latest 2023 OSU bowl projections

“It was kind of rough to deal with at the time,” he said. “I was still a young kid. And it just happened so fast.”

A matter of minutes condensed Hall into a viral image, but only he felt the ripples.

Ten years later, the effects have faded. Time heals, as usual. The incident is no longer a sore spot for Hall, but something he has processed over a decade. He recognizes it as an indelible chapter in a bitter rivalry, an encapsulation of a century’s worth of hostility between Ohio State and Michigan. He holds no bitterness.

“I embrace it,” he said, “because I’m a part of this rivalry forever.”

Ohio State's Marcus Hall is living with the Moment

On a midweek morning in late October, Hall steps into Jack & Benny’s in the Old North. He’s down about 30 pounds after weighing as much as 320 as the Buckeyes’ starting right guard, the result of bike rides along High Street and the Olentangy Trail, a hobby he took up during the coronavirus pandemic, but the 33-year-old former lineman’s large frame still fills a restaurant booth as he orders a vegetable omelet. Friends call him Big Marc for a reason.

Since his last down in the Canadian Football League in 2016, he has worked an assortment of jobs around central Ohio, including as an ice delivery driver and corporate sales manager, and is now pursuing a career as a firefighter. The week following his sitdown with The Dispatch, Hall would meet the Columbus Division of Fire’s oral review board and receive a conditional job offer.

Two years ago, he joined Antonio Pittman, a former Ohio State running back who became a city firefighter, for a ride-along, an experience that encouraged him to apply.

“It’s time to get back to a hands-on job,” Hall said.

Seated at a diner only a mile from the Woody Hayes Athletic Center, he also misses the camaraderie inside the locker room and hopes a firehouse might foster a similar setting.

Hall sees former teammates at reunions and tailgates. He has bought season tickets in previous years, watching the Buckeyes from the stands at Ohio Stadium.

Events at Ohio State are when he is most often recognized, and almost without fail fans bring up the double bird and ask him to recreate it for a photo.

Hall is accustomed to the exchanges and obliges requests for pictures, but refrains from the gesture.

“I can’t be out doing that, watering it down,” Hall said. “These middle fingers are gold.”

The line prompts laughter. Hall chuckles with ease and has an ability to poke fun at himself like anyone reliving an embarrassing college story.

It also allows him to remain mild-mannered in contrast to his defining public moment.

“I ain’t trying to make it like it's something I was proud of and am bragging about,” he said. “It happened. It is what it is, but I'm not going to keep on going around town just taking pictures like that.”

Living in the shadow of campus in Clintonville, the reminders are inevitable.

People have approached him in the most innocuous places, from the gym to the counter at a Bureau of Motor Vehicles office.

In the immediate years, he winced inside when they would recognize him, but he’s used to it these days. He’ll listen to their recollections. Most tell him exactly where they were.

“It went from, ‘Oh my god, I have to talk about this again,’ ” Hall said, “to, ‘Yeah, that’s me.’ ”

The buildup to Marcus Hall's Ohio State-Michigan moment

The tensions were high.

TV sets in the Woody Hayes Athletic Center flashed clips of lions attacking prey or battle scenes in “Gladiator.”

The song “It’s Time for War” by LL Cool J looped on the speakers.

The message was unmistakable.

“It wasn’t like they were preparing us for a football game,” running back Dontre Wilson said. “It was like we were actually about to go to war, like we were about to jump off a plane into enemy territory.”

Wilson was at the center of the skirmish that led to Hall being tossed.

It was early in the second quarter when Wilson returned a kickoff to the Buckeyes’ 16-yard line. After Wilson was tackled, eight Michigan players surrounded him. Shoving ensued.

Hall was with the rest of the offense on the sideline, preparing to take the field as a mob of players formed around Wilson.

“Automatically, I’m thinking it’s a bench-clearing deal,” Hall said.

Hall went out to protect Wilson, pulled by the instincts of an offensive lineman. Seeing the rush from both sidelines, he also didn’t want to be alone. He could imagine watching film with the team the following day and being singled out for not finding his way into the middle of things.

That’s how Hall ended up standing at the 8-yard line in the south end of Michigan Stadium and smacking the side of the helmet of Keith Heitzman, a tight end for the Wolverines, drawing a flag for unsportsmanlike conduct.

Hall expected the personal foul penalty, but not the ejection.

“There’s been way worse stuff that has happened in The Game,” Hall said, “and them dudes still played.”

Hall had watched Ohio State and Michigan from a young age, growing up on the east side of Cleveland. He was only 7 when he saw David Boston and Charles Woodson tangle on the same field.

“That was a full-fledged street fight,” Hall said.

Neither was tossed.

Hall did not watch the remaining quarters after he trudged up the tunnel. There were no TVs in the locker room. He was there alone with Wilson, who had also been tossed. They were left only to follow the oohs and aahs of the crowd and stew in their thoughts.

“It was kind of like torture,” Hall said.

Hall at one point sent a text message to his mom as she watched from home. “I’m sorry,” he wrote.

“I was just thinking about the people closest to me,” he said, “the people that I would care to disappoint.”

A sense of relief filled Hall when the Buckeyes prevailed in the dramatic win, saved by safety Tyvis Powell who intercepted Michigan quarterback Devin Gardner on a two-point conversion attempt with 32 seconds left.

Hall’s double bird is intertwined with the final minute, its cult status partly owed to the triumph.

Fans saw Hall as a legend, not a scapegoat. It would have been easy for them to latch on to the actions had Powell not stepped in front of Drew Dileo in the end zone to pick off Gardner’s pass. They might have panned Hall for a lack of composure had it contributed to a defeat. Passions run the spectrum.

“If we had lost,” Hall said, “a lot more focus would have went on me in a negative way.”

The low point for Ohio State's Marcus Hall

The implications sank in on the Buckeyes’ bus ride back to Columbus.

TV sets aired the highlights of the win at Michigan, including clips of the brawl and Hall’s ejection.

When Hall looked at the screen, he saw his middle fingers blurred out.

“That’s how I knew it was serious,” Hall said. “I violated the FCC out here.”

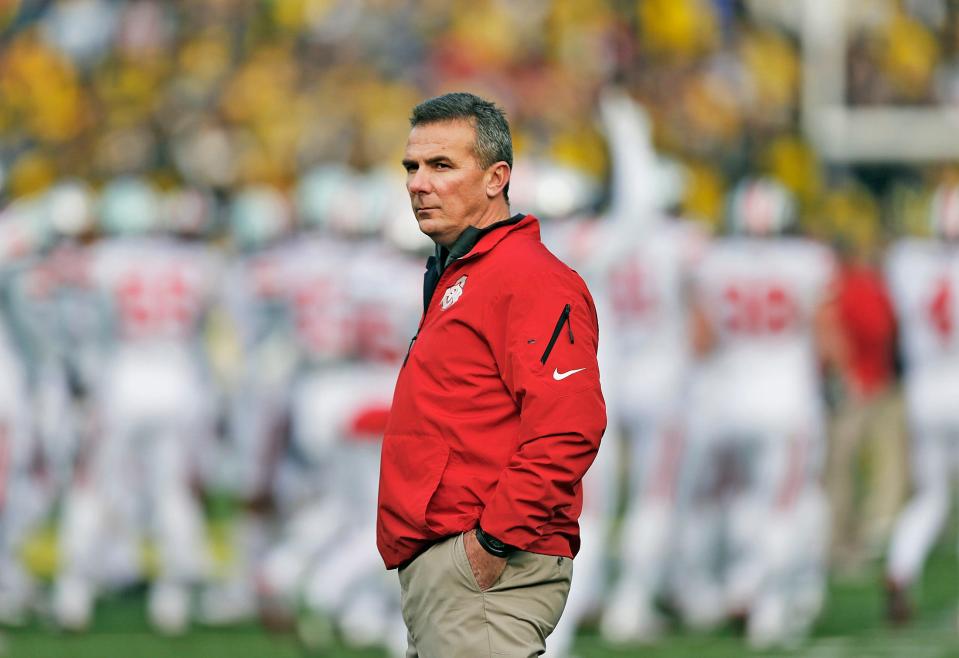

It was at that point the gesture got the full attention of coach Urban Meyer. Hall remembers Meyer turning his head toward the back of the bus and glaring at him. Meyer's face turned red.

“He can’t hide his emotions,” Hall said.

Hall desperately wanted to look away, but their eyes locked. He couldn’t escape the disappointment he absorbed from Meyer’s stare.

“I just could feel how he felt,” Hall said.

A staff member then approached Hall and told him Meyer wanted to meet with him when they returned to the Woody Hayes Athletic Center.

The remaining 45 minutes of the trip were long ones.

In the locker room earlier that afternoon, he and his teammates had cracked up at the screenshots and clips that littered the internet.

“It was outrageous, right?” center Corey Linsley said.

But they all braced for the discipline.

“You know how it goes,” Linsley said. “Something like that catches fire. People start complaining. Something is going to happen.”

Hall sat out the Big Ten championship game the following week as the Buckeyes were upset by Michigan State, ending their 24-game winning streak and keeping them from reaching the BCS national championship game.

Though Meyer announced ahead of kickoff that Hall would not start, he had expected to play and dressed for the possibility. The staff told him to stay ready.

“I thought there was a chance they were going to put me in,” Hall said. “The game just went on and on. I didn’t get it in.”

When Braxton Miller was dragged down by linebacker Denicos Allen short of the first-down marker on a keeper late in the 34-24 loss, Hall could only watch from the sideline at Lucas Oil Stadium.

All the attention affected Hall, but he was accustomed to the scrutiny that trails those who play for the Buckeyes. It paled in comparison to having to miss time on the field.

“I just wanted to help my team win the game,” Hall said. “That was the most hurtful thing for me.”

When the Buckeyes fell, a title shot slipping through their grasp a year after they had been ineligible for the postseason, a wave of guilt followed.

“That made it 10 times worse,” he said. “I just felt bad for teammates, that I had let them down. I’m not saying I’m the reason we would have won or lost, but it felt definitely like that.”

Ten years later, Meyer believes he made a mistake with the suspension.

“He got caught up in a moment,” Meyer said. “You discipline him and move on. You don't sit him for a game.”

The optics weighed on Meyer, who was in his second season at the helm at Ohio State.

“I was probably worried a little bit about perception,” Meyer said, “which I shouldn't. I should worry about the player. Who cares what people say?”

Meyer feels Hall’s ejection at Michigan was severe enough.

“He paid the penalty,” Meyer said.

The circumstances are also not lost on Meyer. It was his first time bringing the Buckeyes to Ann Arbor, and he had dialed up the intensity.

“I take partial responsibility,” Meyer said, “because we had them lathered up ready to go.”

His feelings have softened.

“For some people, it might offend them,” Meyer said, “and it did for me for a while, but not now. That’s part of the game and you wish he hadn't done it, but that does not define who he is. I can promise you that.”

A chance to be remembered

Evelyn Moore is proud of her son.

He helps her with household chores when he visits her in Euclid. He holds the door for her like a gentleman. He is polite.

She sees Hall’s kindness extended to others.

When he worked at a group home for underprivileged children in Groveport, he would take them to Cardale Jones’ charity softball game each summer at Huntington Park.

“He is such a good man,” Moore said.

Moore looks at his good nature, but she knows passions run deep in the rivalry.

To move him in as a freshman at Ohio State in 2009, she rented a van only for it to have a Michigan license plate, prompting a brief protest from her 19-year-old. “We can’t take it,” she remembers him telling her.

“He was so serious about it,” she added.

It turned out fine. The rental was not vandalized.

“Then I started realizing how intense the rivalry was,” Moore said.

Hall started a game as a freshman, replacing J.B. Shugarts at right tackle in an overtime win over Iowa to clinch a berth in the Rose Bowl.

He redshirted in 2010 as his grades dropped, then raised them and returned to become an integral part of the interior of Ohio State’s offensive line, along with graduating with a degree in African-American and African studies.

When the Buckeyes won a school-record 24 consecutive games at the start of Meyer’s tenure over 2012 and 2013 to come out of the depth of NCAA sanctions, it was Hall who started at right guard.

Meyer considers him one of his favorite players.

“He came from tough situations,” Meyer said, “and became a great player that was one of the leaders of our team. I love that guy.”

Meyer said the offensive line was the backbone of their 12-0 season in 2012, paving the way for a top rushing offense led by Miller and running back Carlos Hyde.

“If it wasn't for that offensive line and Braxton Miller,” he said, “there's no chance that team goes undefeated.”

Hall’s career arc at Ohio State would have made for a simple story of perseverance, but it’s overshadowed by his departure in Ann Arbor.

He appeared in only one more game following the ejection, a loss to Clemson in the Orange Bowl, and was not selected in the NFL draft the following spring.

Hall knows he can remind people about blocking for Miller and Hyde, among the Buckeyes’ all-time rushing leaders, or starting 31 games.

“Don’t forget that,” he said.

Still, little matters more than The Game.

The success of the Midwestern powerhouses over the decades has given the rivalry its stature. The stakes have been high in most of the series’ matchups.

But the chippiness is as much a distinctive quality. The montages flicker between these moments, Woody Hayes throwing a down marker, the Buckeyes tearing down the M Club banner and Boston and Woodson trading blows.

It’s why Hall never understood being derided as classless.

“Let’s be real,” he said, “when you talk about that rivalry, you don’t talk about having class.”

A lot of the Ohio State fans agree. Many own T-shirts with Hall’s outstretched arms forming the “H” in “O-H-I-O,” as a commemoration.

The fans who meet Hall often remind him that he epitomized their contempt for the Wolverines. “You let them know how we all feel,” he hears. Some tell him they wish they could have also given the middle finger to so many Michigan fans.

Hall once ordered a pizza from Adriatico’s, and the box included a note reading, “Screw blue. You rock.”

“It gets their blood going,” Hall said.

The support mattered.

Hall needed a couple of years to embrace his double bird. The punishment that followed made it difficult.

But the longer it’s been since he was in scarlet and gray, he can appreciate the lasting mark he left in the minds of fans.

“If that’s how fans want to remember me for that moment in the rivalry,” Hall said, “that’s fine, as long as I’m remembered.”

The hostility reserved for Michigan is as interwoven in the cultural fabric as Script Ohio and endures, as shown by the sight of those middle fingers of a 6-foot-6 offensive lineman.

“I'm thankful,” Hall said, “not that it happened, but to be a part of history.”

Joey Kaufman covers Ohio State football for The Columbus Dispatch. Follow him on Facebook and X, the platform formerly known as Twitter. He can also be contacted at jkaufman@dispatch.com.

Get more Ohio State football news by listening to our podcasts

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: 10 years later, OSU's Marcus Hall embraces double bird at Michigan