Since 'Fail Mary,' ex-ref Lance Easley says he is battling post-traumatic stress disorder

As the 2012 Russell Wilson pass that would soon be known as the "Fail Mary" floated through the Seattle air, Lance Easley was still an anonymous NFL replacement referee.

In his regular life, he was a vice president with Bank of America, a family man, a devout Christian and someone who for decades in California spent his free time refereeing high school football, small college basketball, whatever he could.

Today, everything is different.

It's more than two years since Easley made one of the most infamous calls in NFL history. It left him under siege from the media, both traditional and social. Players and coaches blasted him. Late-night comics mocked him. Irate fans and gamblers hammered him with crank calls and death threats. The controversy extended all the way to the presidential campaign trail with both Barack Obama and Mitt Romney addressing it.

Today, Easley says, the man he was is gone. Perhaps only his faith remains the same. Today, everything else is up for grabs. Today, it's all a struggle.

"Right now I'm just trying to keep my life together," Easley told Yahoo Sports in a series of interviews just as the focus on the Fail Mary returns with the Green Bay Packers and Seattle Seahawks meeting Sunday for the NFC championship. "It's really difficult."

Easley, 55, says he is suffering from severe depression. It's an illness he periodically struggled with during his life but flared up significantly in the past year as he has tried, unsuccessfully, to put that night in Seattle, and the overwhelming pressure that followed, behind him.

He was diagnosed last year, he said, with post-traumatic stress disorder. He managed the original onslaught of attention only to see his life spin out of control in the past year. Crippling panic attacks felt as if his heart was exploding. A fear of leaving the house left him rattled. Depression proved debilitating, making him suddenly ineffective at work.

"It's almost like a funeral," Easley said. "In the days around it you have a lot of support and you make it through. But as time goes by, you still have to process [the loss of a loved one]."

He sought treatment, both aggressive counseling and doctor-prescribed drugs. It didn't always help. There were suicidal thoughts.

"I felt like I didn't want to be here anymore," Easley said. "I never acted on it. It was horrible to have those thoughts. I hated having those thoughts."

In July 2014, Easley could hardly function. His doctors felt unable to control the situation and wanted to be able to watch him more closely as they changed his medicines. Under their advice, he said, he entered the Vista del Mar Hospital, an acute psychiatric facility in Ventura, Calif.

A week later he transferred to the Balance Treatment Center, a mental health rehab center in Calabasas, Calif., where he stayed through August. Upon release, he went through near daily counseling on an outpatient basis. He relapsed in November, he said, and returned to Balance Treatment for three more weeks and is now an outpatient again.

Since June, per doctor's orders, he's been on medical leave with Bank of America. His 30-year career is now stalled out. His finances are a predictable mess. In September he says he separated from his wife of 28 years.

He no longer feels comfortable in his home community on the Central Coast and is spending much of his time in Los Angeles. There have been days he, a guy whose life once consisted of racing around from one activity to the next – work, family, church, games – didn't want to see anyone or do anything.

He hasn't refereed anything of late, blackballed, he said, from all but high school work for crossing the union line. Even then he's not sure he could handle the pressure.

It's the saddest twist for a comically inept NFL play, a blooper for many fans. What most can only sort of remember, Lance Easley can't forget.

And it's crushing him.

"I am not the same guy I used to be," he said.

– – – – – – – – –

Sometimes, a lot of times, actually, Easley wonders why Wilson's last-second pass couldn't have just hit the turf. Or why Green Bay didn't play smart defense and just bat the ball away.

"Why did they try to catch it?" Easley asks.

The Packers' M.D. Jennings not only tried to catch that pass back in 2012, he did. Only so did Seattle's Golden Tate, who wrestled his way in there. When both players wound up with a share of the ball, Easley knew the call, any call, was going to be controversial.

He boldly signaled touchdown, ruling it simultaneous possession. Back judge Derrick Rhone-Dunn waved his arms, calling for a stoppage of the clock, even though it was already out of time. It looked like amateur hour on "Monday Night Football."

It was. Both men were replacement refs. Easley never called anything higher than California junior college football when the NFL hired him to fill in for, and put bargaining pressure on, the locked out regulars.

Every ref on the field missed an obvious pass interference by Tate. Replay couldn't do much, so the call stood. Seattle won, 14-12, even if many thought it was an interception and Green Bay was cheated.

Immediately, Easley's world blew up.

A man who joined the Marines out of high school, who spent years in sales, who as a ref sought the big moments of making big decisions suddenly felt fear, felt helplessness, felt like the most mocked and hated man in America. He felt besieged.

He wasn't used to such a thing, hadn't built up years of thick skin and coping techniques needed to live in the public eye. He was a nobody and liked it that way. Modern connectivity makes everything spin faster. He lacked any of the infrastructure (agent, publicist, lawyer) around him to handle it, like a scandal-ridden politician or Hollywood star would have.

"I was completely under attack," Easley said.

And, for the most part, alone. It proved too much.

– – – – – – – – –

Easley understands the doubts that come with admitting mental illness, especially as a man. He knows telling America he is suffering from PTSD from something as seemingly trivial as the Fail Mary will be met with scorn and skepticism.

Releasing personal medical information, admitting to a taboo illness is terrifying to him, he said. When he was an inpatient at Balance Treatment he lived in fear that it would get leaked out to TMZ, his story told without context.

"A lot of people don't understand mental health issues," Easley said.

He knows people will think he should just shake it off, power through, that this was no big deal, that so many other people are dealing with real tragedies, real challenges, real stuff.

He knows because he was one of them.

He says he tried. He recognized the storm and tried to weather it.

He went back to work. He hunkered down. He tried to own the decision (he still argues he made the proper call). He talked to anyone and everyone about it, from reporters to old friends to complete strangers.

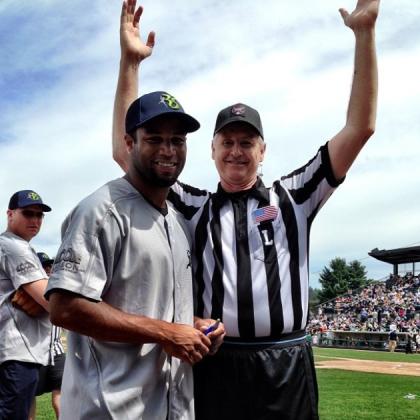

He tried to bring levity to the situation by serving as a guest umpire at a charity softball game run by the Seahawks' Richard Sherman. Of course, a light-hearted photo with Tate riled some people up again.

He began giving moving speeches about surviving life inside a modern storm of overnight celebrity and controversy. He figured talking about it would be a good thing. It led to a profound book, "Making the Call: Living With Your Decisions."

He put together a four-point survival plan, D.E.A.F., to help tune out all the critical noise that comes from bullying. It was meant to be self-empowering.

• Don't be a victim.

• Embrace the stress and pressure.

• Adopt a good attitude, it's the one thing you can control.

• Form a foundation of strength to handle the storm.

For awhile he was DEAF. It worked. Then it didn't.

He likened it to an earthquake, which lets you know exactly how strong the foundation to your house is. Even if the structure survives the initial shake, the damage is done. It's just a matter of time.

"It doesn't cause all the problems, it pushes it over the top though," Easley said.

– – – – – – – – –

The possible break-up of his marriage is particularly painful. After 28 years, raising a now grown son, he thought it was solid. Now he questions everything.

"Maybe we weren't really that close" he said before sighing. "I don't know."

He knows people think he's being dramatic or ridiculous, but, he argues, why would he do this? Who would want this life? Who would admit this? This is the exact opposite of who he was.

He blames no one, not the NFL, not even the people who heckled and harassed him. "Hate is waste of energy," he said.

This story isn't coming out as part of a lawsuit. This isn't a cry for attention. This isn't a way to build himself up. He isn't asking for anything. He didn't go seeking it. He responded to a media inquiry and he won't hide how he feels.

He said he goes through counseling daily with people suffering from depression who are ashamed of their illness.

So Lance Easley isn't going to be ashamed.

He is sick. That shouldn't be embarrassing to admit or frightening to discuss.

"If you don't struggle with it, I guarantee you there is someone in your circle of family or friends that are affected by it," Easley said. "It knows no boundaries. Young, old, white, black, male, female. We know what people think, 'You're just lazy, you're just making excuses.'

"Believe me, we all wish we could just flip a switch."

– – – – – – – – –

After high school in the late 1970s, Easley joined the Marines, but fused bones in his feet caused him to be honorably medically discharged soon after boot camp. He enrolled at UCLA and found his love of sports drew him to referee intramural games.

It led to a three-decade career as a ref, mostly high schools, topping out at Division III basketball and junior college football. He'd applied once to the NFL but was rejected.

When word circulated in the summer of 2012 that the league was looking for potential replacements if its lockout of the union stretched into the season, Easley hesitated to apply. A friend finally convinced him to do it. At his age, and with his still injured feet, his career could go on only so much longer. Why not test himself at the highest level?

"Besides, no one thought it would come to that, everyone thought they'd reach an agreement before the season," Easley said.

He got a call back, went to Atlanta for a tryout and made the cut. The lockout dragged. On opening day he found himself at Soldier Field for Indianapolis-Chicago. He marveled at the size of the stadium, the intensity of the action and the speed of the players.

By Week 3 of the season though, frustrations with the subpar calls of replacement refs reached a boiling point. Games were choppy, filled with penalties, often with players either fighting each other or complaining after each play. The coaches screamed only louder. Fans were restless and angry.

The perfect storm culminated with Tate and Jennings fighting for the ball on the final play of the game. Such a scenario was almost unheard of, a decision that would've challenged the best of the best. Does one have more possession than the other? Simultaneous? Anything?

"No matter who was back there it was going to be a big, brutal call," Easley said. "In the days after I called the NFL and asked if they had ever remembered seeing that play before. There was dead silence."

Easley made a decision. A lot of people disagreed. It was still just one call in one NFL game. As fans roar over various controversial decisions in this year's playoffs, it certainly wasn't the last.

"Nobody died," Easley said. "There were no laws broken. It wasn't scandalous. There was no sex tape. I didn't do anything wrong. It just happened to be a contentious call right when everything was spiraling out of control."

It shouldn't have been a big deal. It was.

– – – – – – – – –

Three days after the Fail Mary, the NFL and the union reached an agreement. For that, Easley jokes, fans should be grateful the play occurred.

They weren't. They aren't, although, in truth, almost everyone else has moved on. It's Easley who remains stuck.

"Health, finances, marriage. If you have trouble in one of those it can be tough," he said. "I have all three."

His life now is counselors, doctors and divorce attorneys. He's trying to rebuild, but knows he first needs to recover.

He isn't without support. There's a grown son. There are friends and family who have stuck with him. The NFL, he said, remains available for help. He said he's done Bible study over the phone with former coach Tony Dungy and broadcaster James Brown.

He knows this is about him, this has to be done by him. He just isn't going to be quiet or apologize for it – not the illness, not the cure.

"I know I'll recover," he said. "I know it. It's just going to take time to get thru it."

This isn't what he wanted. It's not what he envisioned as he stood in the corner of that Seattle end zone, ball soaring through the air, a dream opportunity about to turn modern media nightmare.

"I watch NFL games now and I'm like, 'Was I really there?'" Easley said. "It doesn't seem real."