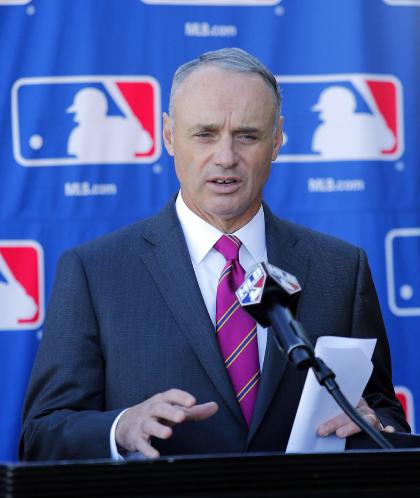

New commissioner Rob Manfred maintains connection to soul of the game

It’s not a requirement or anything, but we like there to be a soul beneath the suit, behind the nameplate, somewhere in there among the brooding bodyguards and backdoor entrances and corporate gamesmanship.

We don’t ask that baseball’s commissioner be a desperate romantic. The game has enough poets. Just that there’s a little more to him than shiny town cars and company lines.

If it matters, and for some reason it does, it always does, it’d help if he cried the day Thurman Munson died, stayed up ’til dawn when the Tigers won it all, fell asleep on the porch to Jack Brickhouse. That there once was a little boy in there, before the Ivy League, before the rat race, before the nine-to-fives, before everybody forgot what you looked like when he laughed.

We are not blind to what baseball is, that being a $9 billion industry, in no small part because of the deeds of its last commissioner. But it can’t start and finish there, because that’s boring and really quite, well, soulless.

So, yeah, keep the game upright. Try to be sure all the World Series are played. Figure something out in Oakland and in Tampa. Protect the game from the bad guys dressed as doctors. Protect the good guys from themselves. Put the games on television. Give the small towns a shot. End the season before November and the games before midnight. Get the pitcher back on the mound. Get the batter back in the box. Gaze out from your Park Avenue corner office and put a DH in every lineup.

And every once in a while, remember that day. The requirement is that we recall it to the last detail, that day when we were unafraid, when dad – or mom – pushed ahead through the crowd, towing this knucklehead little kid toward something we’d never seen before. That day. Everybody, it seems, has one.

“August 10, 1968,” Rob Manfred said. “I was 10.”

Bob Manfred, his wife, Phyllis, and their three children – young Robbie among them – drove four hours from Rome, N.Y., to Elmsford, N.Y., on a Friday. After a night at the Howard Johnson, they’d cover the last of the trip the next day, down to the Bronx, where the Yankees would play the Twins.

“I can remember it as vividly as any day in my childhood,” Manfred said. “The first time I walked into a major league ballpark. Who I was with. When. Who played. My favorite player hit two home runs on Saturday. Old Timers’ Day on Sunday.”

They’d push through the turnstiles and Robbie would run the rest of the way.

“It was like somebody opens up a picture in front of you,” he said. “The light spreads, opens up, and there you are.”

The Yankees lost. But Mickey Mantle hit two. They lost again the next day, and while Mel Stottlemyre was knocked from the box early, he was still the little second baseman from Rome’s favorite pitcher.

Coming up on 50 years later, Manfred, 56, very nearly laughed at the memory, at the art of placing the excitable boy from then beside the serious man with the corner office on Park Avenue today, the man who will become the game’s 10th commissioner on Sunday.

“Every single time that I walk into a ballpark I get that same feeling,” he said.

The job clouds some things and perhaps has hardened him the way nuisances such as jobs and age can. But, he said, not that. In fact, when the job put him in the backs of those town cars and led him through special entrances and guided him through underground tunnels to reach the ball field, he found he missed the more formal introduction of height and breadth and … drama. He missed the spreading of the light.

He’s been full-time at Major League Baseball since 1998. A Cornell and Harvard Law graduate, he’s worked the economic side. He’s worked the labor side. He’s worked the performance-enhancing-drug side. He’s buttoned his top button and tugged his tie straight and reported to work at Bud Selig’s right hand, and so the baseball job generally has seen more elevators and file cabinets than ballparks. He survived a scary challenge to Selig’s wishes that he be Selig’s successor, and in the five months since he has gotten on with the business of transition, of leading, of sorting priorities. He is smart. He is tenacious. And now the job is to organize 30 owners toward one end, like tethering grade-schoolers on a field trip to the planetarium, as Selig did for an entire generation.

Manfred was raised in Rome, N.Y., an hour’s drive from Cooperstown. His father, Bob, was an executive for Revere Copper and Brass and ran the local youth basketball league (former big leaguer Archi Cianfrocco played for him). His mother, everyone called her Phyd, taught at Francis Bellamy Elementary School. (Bellamy, who was from Rome, wrote the Pledge of Allegiance.) They’ve since retired and moved to North Carolina.

Rob Manfred left Rome for Le Moyne College in Syracuse, transferred to Cornell, and earned his law degree at Harvard.

Thirty years later, he was on a speaker phone from New York, explaining his immediate concern is for pace of play, how the game, he said, “Must stay in tune with the way we live our lives,” which is somewhat more up-tempo than endless batting glove adjustments and pitching changes. Beyond that, he said, he wonders if the game needs to respond to the sudden offensive downturn, which either is a trend worth addressing or a cyclical event best left to itself.

It’s his game now, his and the owners and the players and the people who fill the ballparks, who take their own boys and girls for their first times. They pile into their cars and they find their own HoJo’s and they, too, leave the turnstiles at a sprint, because their Mickey Mantle is hitting cleanup that day.

It’s how you find the soul of the game amid the reality, the drudgery, the calendar of the day. Even when the game’s an office job. Even when it’s your responsibility. Even when the only way in is on a freight elevator.

“My pre-eminent thought is the enormity of the responsibility this job entails,” he said. “I feel that way because – for TV ratings, revenue, those things, of course – but I think there’s something very special about the relationship between our culture and baseball. And it’s my responsibility to maintain that relationship.”

We don’t require them to see it this way. To feel it this way.

But, you know, it’s nice when they do.