'Took a lot of guts': Charlie Scott persevered in breaking color barrier at North Carolina

In February for Black History Month, USA TODAY Sports is publishing the series “28 Black Stories in 28 Days.” We examine the issues, challenges and opportunities Black athletes and sports officials continue to face after the nation’s reckoning on race following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. This is the third installment of the series.

The full story is nowhere to be found in the box score or game film from one of the great performances in the history of the ACC basketball tournament.

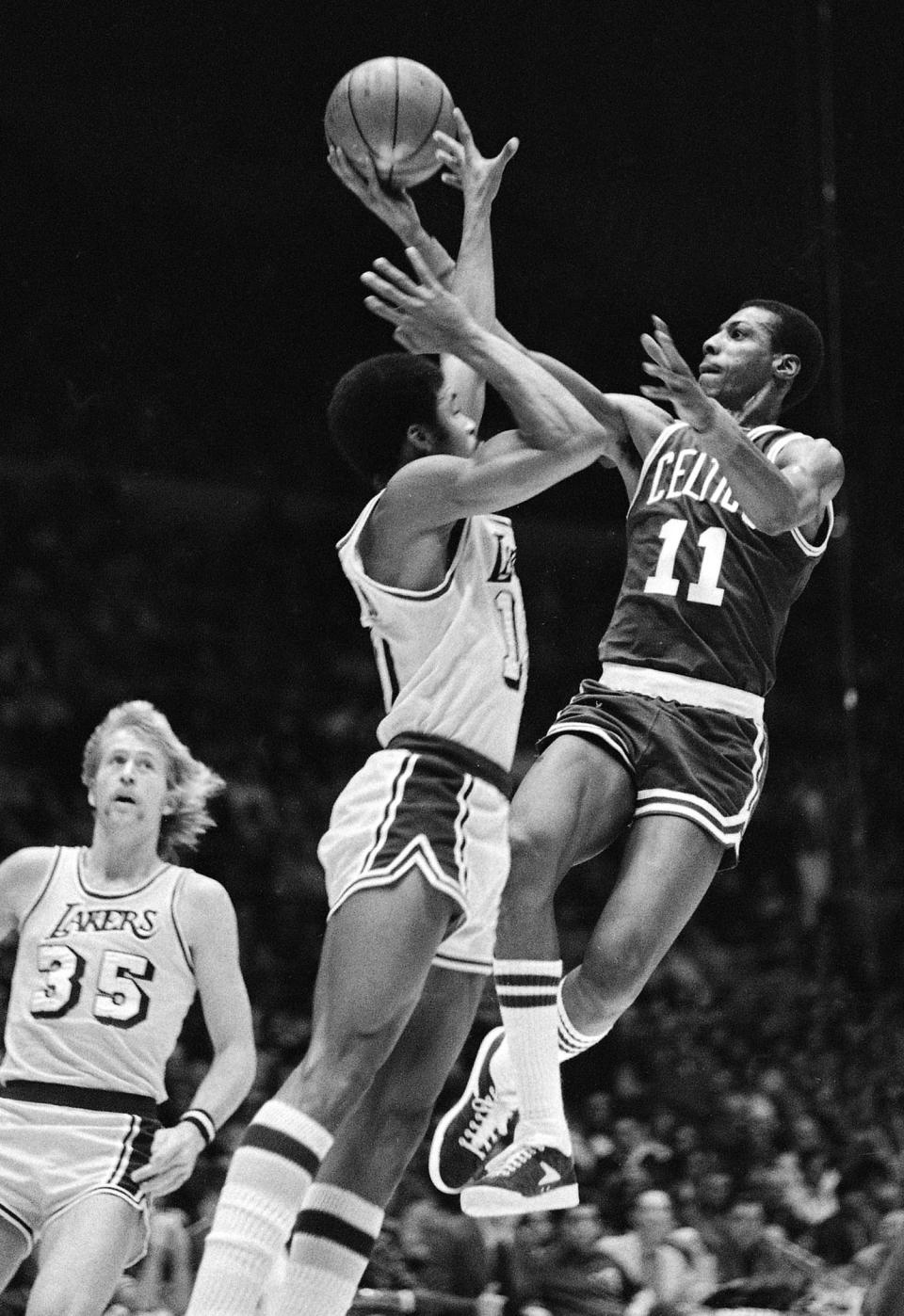

Charlie Scott, the first Black scholarship player at North Carolina, scored 40 points in the 1969 title game while leading the Tar Heels to an 85-74 victory over Duke. Video highlights are compelling, but there’s no visual record of what happened next.

Scott said he went directly from the arena to his hotel room instead of joining his teammates to celebrate.

At the time, he explained, he was an outcast in the South at gatherings where only white people were in attendance.

"Why would I go with them, where everybody would be uncomfortable, just so I could be with my teammates so they would show they weren’t biased," Scott told USA TODAY Sports. "Why would I spoil their college life? They didn’t sign up for that."

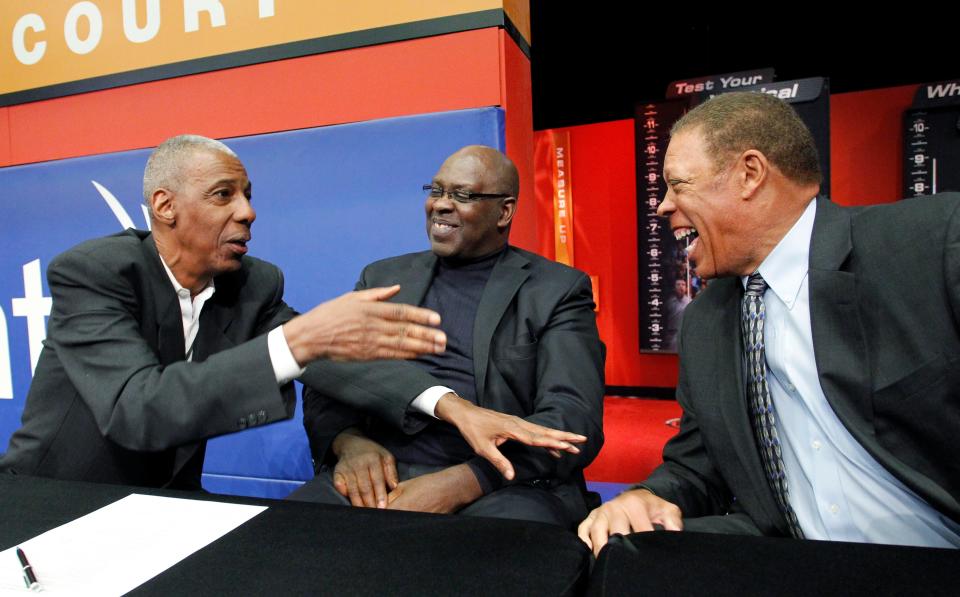

More than 50 years after his scintillating collegiate career, Scott, 74, recalled what he faced while breaking the color barrier at North Carolina.

Born in New York, he moved to North Carolina at 15 for his final three years of high school before enrolling at the state's flagship university in 1966.

"It took a lot of guts for him to do what he did," said Joe Brown, one of Scott’s former teammates. "We accepted Charlie. We loved Charlie. He was one of us. But I can see where he might feel uncomfortable at certain places and certain events socially because of the way it was in the South in the 1960s.''

A boycott?

There were so few Black students at North Carolina, Scott said, that he ended up spending most of his free time at nearby historically Black colleges. He said a sense of social isolation is probably the reason he married his sophomore year.

The marriage lasted one year.

On the court, he thrived.

Scott, who was a 6-foot-5 guard, won first-team All-America honors during his junior and senior years, and helped lead North Carolina to the Final Four in 1969. He also won an Olympic gold medal in 1968 after his sophomore year.

But, as North Carolina’s first Black scholarship athlete, he said always felt pressure.

"It was never a thrill or enjoyment," Scott said. "It was always a point of relief."

As a junior, Scott found himself immersed in turmoil the week after his heroics at the 1969 ACC tournament championship game.

More: In hiring Black head basketball coaches, the Big East stands alone among power conferences

Despite his stellar season, he was not voted ACC Player of the Year. That honor, as determined by a vote of the media, went to John Roche, a white guard with South Carolina.

Additionally, Scott was not on all ballots for first team All-ACC.

Scott said the Player of the Year honors going to Roche, who is white, shows "how racism could be very obtuse."

The news of Roche winning the award came the week North Carolina was playing in East Regional of the NCAA tournament in College Park, Maryland. With frustration building, Scott considered sitting out North Carolina’s game against Davidson in the Elite Eight.

Before the game, Scott said, North Carolina assistant coach John Lotz drove him around for an hour before Scott decided to play.

"We talked and it was just the circumstance of understanding if I (did not play) it would end up really hurting my teammates more than the people I wanted to hurt,'' Scott said.

Against Davidson, Scott scored 32 points and made the game-winning basket in an 87-85 victory.

"Vindication was really a great relief," he said, "but it still didn’t change the outcome (of the Player of the Year vote)."

The accolades piled up.

He was a three-time NBA All-Star, won an NBA title with the Boston Celtics in 1976 and was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2018.

More: A white player shattered his jaw, ending Johnny Bright's Heisman Trophy dreams

Dean Smith 'always there for me'

North Carolina coach Dean Smith had to be pulled back from a South Carolina fan who called Scott a "big, Black baboon" after a North Carolina victory at South Carolina, Scott has recounted.

Scott named his younger son, Shannon Dean Scott, in honor of his former coach.

"Coach Smith was the most important person in my life," Scott said. "He was the person that was always there for me."

Scott said his recruitment at North Carolina included a meeting with the school’s chancellor and president.

"They said to me, and I’ll always respect them for it, they said your time here will not be as good as your children's time here," Scott recalled. "And they were absolutely correct.

"Their point was that I what I was doing was making sure that my children would have a great time. And happily, two of my kids did graduate from North Carolina and they had the greatest time of their life in college."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Charlie Scott persevered in breaking color barrier at North Carolina