For the third straight winter, avian flu is taking a toll on domestic and wild birds

Persisting for the third consecutive winter, highly pathogenic avian influenza, or bird flu, continues to take a toll on domestic and wild birds in the U.S. and beyond.

In recent weeks outbreaks of the H5N1 variety of the virus has led to the losses of commercial flocks in Barron, Trempeleau and Washburn counties in Wisconsin and a game bird production and hunting facility in Pennsylvania.

It has also affected wild birds, including cases in mallards, northern pintails and trumpeter swans in Wisconsin in the last month. And it continues to be found in more mammal species, including the first known case in a polar bear in Alaska.

The outbreak is already the deadliest ever for U.S. poultry producers. Since February 2022, the H5N1 outbreaks and related culling operations have wiped out a record 79.3 million poultry across 47 states, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

More: Outdoors calendar

It has surpassed the 2015 outbreak of subtype H5N2, which hit about 49 million birds at U.S. farms. At a cost of $1 billion, that outbreak was deemed the most costly animal health emergency in U.S. history, according to the USDA.

No financial estimate has been produced of the current outbreak but it is expected to result in record monetary losses, too.

Avian flu viruses are highly contagious and often fatal to domestic poultry and wild birds. The disease can be spread by contact with infected birds, commingling with wild birds or their droppings, equipment, or clothing worn by people working with the animals.

The commercial losses since late November in Wisconsin include turkey flocks in Barron County (183,800 birds) and Trempealeau County (72,200 birds). Details are not yet available on a more recent HPAI outbreak at a commercial facility in Washburn County.

The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection announced it is working with the U.S. Department of Agriculture on a "joint incident response" at the facilities. In an effort to prevent spread of the disease, all birds on the properties were depopulated and the businesses will not be allowed to move poultry products. The killed birds will not enter the food system.

When HPAI is diagnosed in a Wisconsin flock, a control area is established within a 10 kilometer area around the infected premises, restricting movement on or off any premises with poultry, according to DATCP.

The disease also has hit several game bird production facilities in the U.S. In December HPAI was found in ring-necked pheasants at Martz’s Gap View Hunting Preserve, a 1,300-acre facility in Dalmatia, Pennsylvania. About 100,000 birds, including pheasants, chukar, Hungarian and French red-legged partridges, were killed by animal health authorities after the finding.

Signs of HPAI in birds include sudden death, lack of energy or appetite, difficulty breathing and stumbling or falling down and inability to fly.

Wild birds can be infected with HPAI and show no signs of illness, according to the USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Infected birds can carry the disease to new areas when migrating, potentially exposing domestic poultry to the virus, as well as other wild birds.

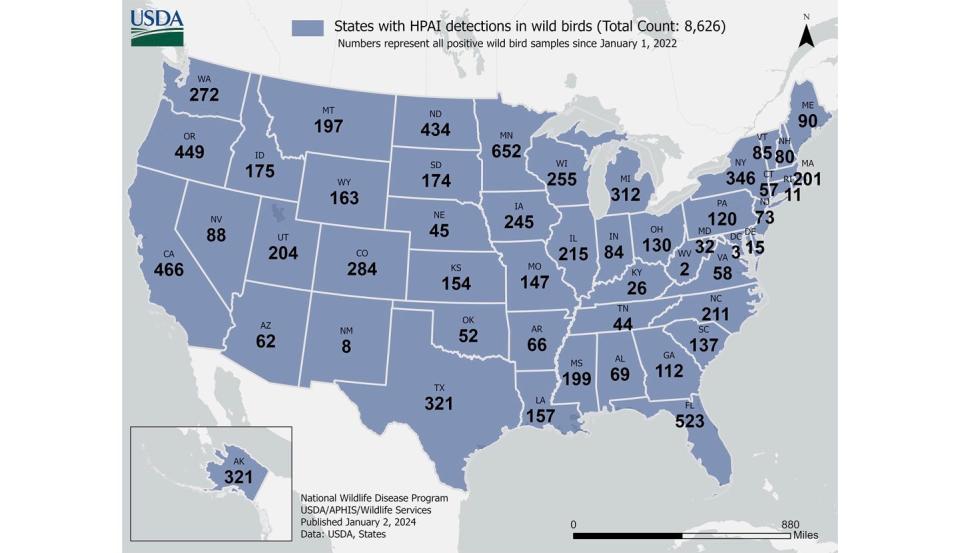

Since Jan. 2022 the disease has been documented in wild birds in all states except Hawaii, according to APHIS.

The intensity of the disease among wild birds appeared to decrease last year, perhaps due to immunity building among flocks.

In 2023 in Wisconsin, for example, wildlife officials did not document any widespread die-off due to HPAI in the state's wild birds.

That contrasted to 2022, when the disease killed more than 1,000 Caspian terns on two islands along the Door Peninsula in northeastern Wisconsin, according to Sumner Matteson of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. The deaths were estimated at 64% of the breeding population of the state endangered species.

The virus also led to extremely poor survival of bald eagle chicks in 2022, according to data collected by a volunteer Bald Eagle Nest Watch program run by Badgerland Birding Alliance (formerly Madison Audubon).

In 2022 volunteers with the program found just 35% of 110 nests produced an eaglet to the fledgling stage. Over the previous four years the success rate was about 80%.

In 2023 89% of nests fledged at least one eaglet, according to program managers.

So while the tide may have turned among wild birds, wildlife and domestic health officials are still watching the disease carefully.

It was found for the first time last fall in a polar bear. The animal, in northern Alaska, was found dead in October and tested positive for the disease.

The virus has also been found in grizzly bears, seals, foxes and squirrels, among other mammals.

While HPAI cases in humans are extremely rare, health experts advise people not to handle dead wildlife with bare hands and not to eat animals that appear sick. To dispose of a wild animal carcass, the DNR recommends people wear gloves or an inverted plastic bag and either bury the carcass or double-bag it in a garbage bag and place it in the trash.

The DNR also has a form to report dead birds at dnr.wi.gov.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Avian flu takes toll on domestic and wild birds across Wisconsin, U.S.