Smith: 'Vampire of the Great Lakes' rises; Sea lamprey numbers increase in Lake Michigan

RACINE - The lights were dimmed, a projector switched on and 25 members and guests settled into their seats at at the Fifth Street Yacht Club in Racine for the June meeting of Salmon Unlimited of Wisconsin.

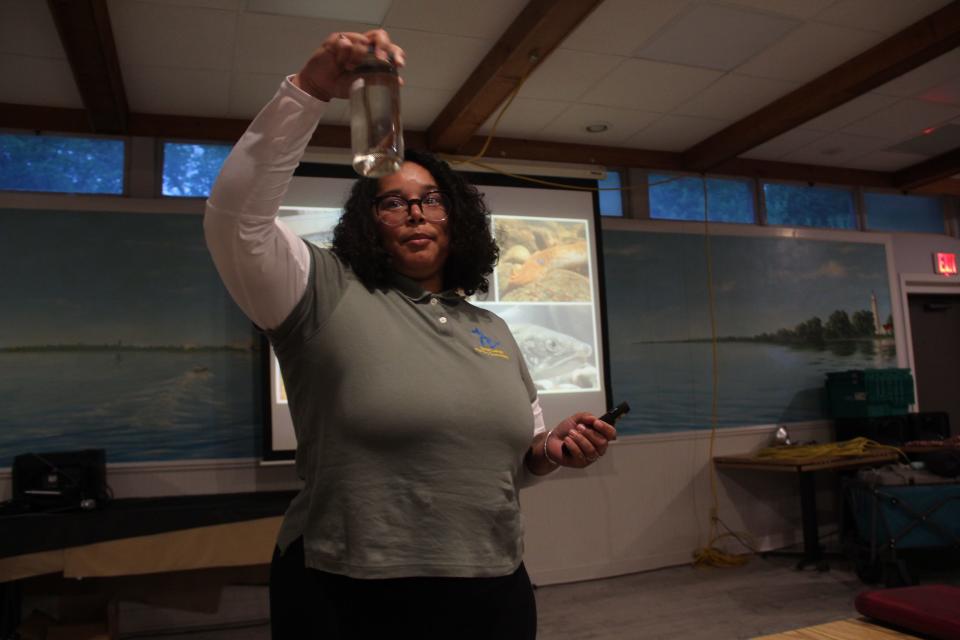

Next on the agenda: "Vampire of the Great Lakes," a presentation by Christina Carter of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

As its name implied, the talk would be part ecological horror show but also highlight a fisheries management success story and, especially in light of a recent development, offer a cautionary tale.

Carter had the group's rapt attention.

"How many of you have seen a sea lamprey?" she asked.

Every person in the room raised a hand.

"That's not good, is it?" Carter responded. No reply was needed from the crowd.

The sea lamprey is a parasitic fish that ranks among the most destructive aquatic invasive species to enter the Great Lakes.

Native to the Atlantic Ocean, the fish (scientific name Petromyzon marinus, or sucker of stone from the sea) swam into inland North American waters after canals were built to ease shipping. The upper Great Lakes were especially vulnerable to invasive species after the Welland Canal was built to bypass Niagara Falls.

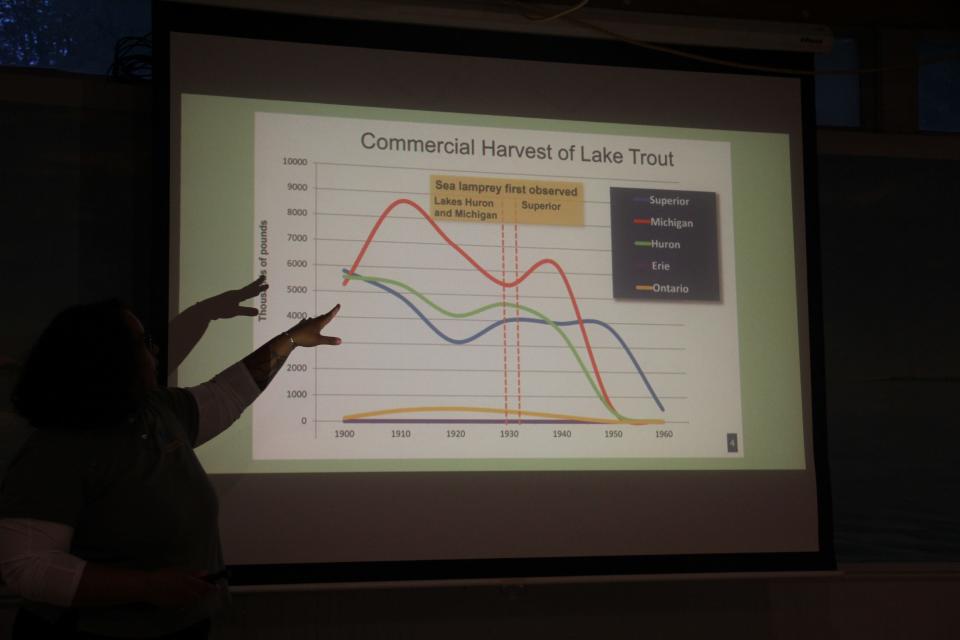

Sea lampreys were first observed in Lake Erie in 1921, in Lake Michigan in 1936, in Lake Huron in 1937 and in Lake Superior in 1946, according to the GLFC.

Coupled with overfishing, the sea lamprey had a devastating impact on lake trout, a top native predator species in the Great Lakes, said Chuck Bronte, research fishery biologist and project manager with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Within a decade after the sea lamprey arrived in Lake Michigan, commercial lake trout harvests began to plummet. In 1920, Lake Michigan commercial fishermen landed 7 million pounds of lake trout, according to GLFC data. The harvest fluctuated to 5.4 million in 1930 and 6.3 million in 1940. But after it hit 6.9 million in 1943, it went into free fall: 4 million in 1946, 1.2 million in 1948 and 54,000 in 1950.

In 1953 commercial fishing was closed for lake trout in Lake Michigan.

Sea lampreys have been largely unchanged for 340 million years and have survived four mass extinctions, according to biologists.

The reasons were put on full display during the species invasion of the Great Lakes: the long, slender fish is formidable, adaptable and prolific just as it is.

The sea lamprey has a disc-shaped mouth it uses to suction to the side of a fish. Once attached, its rows of teeth dig into the host's flesh and a sharp tongue rasps through scales and skin.

The parasite then feeds on the fish’s body fluids by secreting an enzyme that prevents blood from clotting.

A single lamprey will eat about 40 pounds of fish during its lifetime and grow to about 2-feet-long, Carter said.

"They either kill the fish or leave it severely compromised," Carter said. "If you are a trout or salmon, you definitely don't want to have a sea lamprey in your life."

Fish species of the Great Lakes did not evolve with sea lamprey and therefore are not able to tolerate a parasite of its size, according to the GLFC.

Through the mid-1900s, the sea lamprey was a driving force in the "collapse of the Great Lakes ecosystem and the economy it supported; tens of thousands of jobs were lost, property values were diminished, and a way of life was forever changed for millions of people," the GLFC said in a history of the region.

Sea lampreys adapted well to the fresh water lakes and found excellent spawning conditions in hundreds of miles of tributaries.

Additionally, female sea lamprey are fecund and can produce up to 100,000 eggs.

The ancient parasitic fish killed more than 100 million pounds of Great Lakes fish annually in the years after its arrival, five times more than the commercial harvest.

It also helped lead to the 1954 formation of the GLFC, a commission of representatives from the U.S. and Canada to address regional fisheries issues.

The body coordinates sea lamprey control efforts around the lakes. And thanks to fisheries scientists from a host of agencies, universities and organizations, a treatment has been used for decades to effectively limit sea lamprey reproduction around the Great Lakes.

The primary control is 3-trifluoromethyl-4-nitrophenol (TFM for short), a chemical added to tributaries where sea lampreys spawn. The chemical blocks the respiration process of the sea lampreys. Some rivers also have sea lamprey traps or barriers.

Each year, GLFC managers make a plan to add TFM (referred to as a lampricide) to a portion of the approximately 500 streams in the region that produce most of the sea lamprey larvae.

Crews from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Fisheries and Oceans Canada treat the streams; the chemical kills about 98% of the sea lamprey larvae, according to the GLFC.

The strategy significantly reduced sea lamprey numbers and, coupled with robust stocking programs, allowed a world-class salmon and trout fishery to emerge in the wake of the lake trout collapse. The Great Lakes fishery is now estimated at $7 billion annually, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The sea lamprey control work costs about $25 million annually and is labor intensive. The primary sea lamprey spawning rivers are treated on about a three-year rotation.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic threw a wrench in the works. In 2020 only about 25% of the planned treatments were conducted. In 2021, the number rebounded to about 75%, Carter said.

And by this year the normal, full schedule has resumed.

But the reduced treatments in 2020 and 2021 appear to have allowed sea lampreys to resurge.

In Lake Michigan, the adult sea lamprey index in 2022 was 49,000, above the three-year (2020-2022) average of 32,000 and the goal of 35,000, according to GLFC data.

In Lake Huron, the 2022 index was 57,000, also above the three-year average of 54,000 and the target of 31,000.

Similar increases were observed in Lake Ontario and Lake Erie.

In Lake Superior, the adult index in 2022 was 19,000, below the three-year average of 23,000 but above the target of 10,000.

Bronte said sea lampreys will attach to all salmonids in the Great Lakes. But in Lake Michigan they are most prone to parasitize lake trout with chinook salmon second. In Lake Huron, it's the opposite.

"We're seeing less healed wounds on chinook than on lake trout," Bronte said. "Which could mean the mortality rate is higher on chinook than on lake trout, but it's tough to tease out at this point."

The bottom line to the story is: sea lampreys not only suck on their victims like vampires but they also are nearly impossible to eliminate.

"Many sport anglers think the sea lamprey problem is solved," Bronte said. "But we can't let off the gas on this one. As soon as you let off on treatments these animals come back. This is a forever thing."

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Sea lamprey numbers increase in Lake Michigan