The secrets behind Smyrna's 'earthquake,' Delaware's hardest-to-stop 2-point play

The story of football, its strategy and tactics, is a story of evolution.

An offense finds a solution to a problem posed by a defense. The defense stifles it, presenting a new problem. The offense responds and changes again. And so on.

For Smyrna football in 2015, the problem was the 2-point conversion. Mike Judy, hired the previous year as Smyrna's head coach, had decided the Eagles would never kick an extra point. That meant going for 2 every time, typically a low percentage proposition. The ball is spotted at the 3-yard line. With fewer blades of grass to cover, the advantage swings to the defense.

Smyrna offensive coordinator Mike Marks huddled with his dad, Tony, in his basement. They devised a funky-looking formation for the express purpose of punching in 2-point plays. No wide receivers. No quarterback. Nobody detached from the offensive line or backfield.

They called it earthquake, sticking with a tradition of naming formations after natural disasters that Mike picked up while on the coaching staff of K.C. Keeler at the University of Delaware in 2003. Rooted in principles of the double wing, an old-school style of power football, it would be the complete opposite of Smyrna's primary spread attack.

Nine years later, earthquake is still Smyrna's go-to formation for short-yardage situations, a key to one of the most prolific offensive runs in state history. The formation has grown to be a part of the school's offensive arsenal in the open field, too.

In 2015, the year Smyrna introduced earthquake, the Eagles converted 82% of their 2-point attempts. That year they won their first-ever state championship, highlighted by eventual two-time state offensive player of the year Will Knight.

They won Division I titles again in 2016 and 2017 and the Class 3A title in 2022. Earthquake played an evolving role each year.

"It's just really unstoppable," said Yamir Knight, the youngest of three Knight brothers who starred at Smyrna and the centrifugal force of the earthquake formation in the 2022 championship run. "That's where we really pride ourselves. ... We have to have an unstoppable mindset. You have to go out there and play with a lot of attitude."

Entering the 2022 season, Tony told Mike he would write a book about earthquake if they won the state championship. Tony has found in 45 years of coaching football that if you find something that works, you let people in on it, make a contribution to the public bank of shared knowledge.

Earthquake and the philosophies behind it is a small slice of football lore that Tony and Mike, father and son, can own together.

The roots of earthquake

Mike's first game as Smyrna's offensive coordinator in 2014 was a disaster. Name something an offense could do wrong and there's probably an example in the tape of the Eagles 22-8 loss against Glasgow.

The one play they ran well was an afterthought. Mike told the skill players to pile in tight to the offensive line and bulldoze forward. Quarterback Brandon Bishop took a shotgun snap and ran straight ahead. He got lost in the offensive line for three seconds, Mike said, and then squirted out the other side for a 12-yard touchdown.

After the game, the prospect of being fired felt closer to Mike than the idea of catching up to Salesianum and Middletown.

"The only touchdown we could muster was this piece of crap," Mike said.

But it continued to work throughout the season. They used the play in short yardage but not at the goal line. Defenses almost always countered it the same way.

When Mike and Tony, who came on as an assistant coach in 2015 after retiring to Lewes, met in Mike's basement to design their 2-point package, the pack-it-in play served as a reference point. But the new formation they crafted was far more refined.

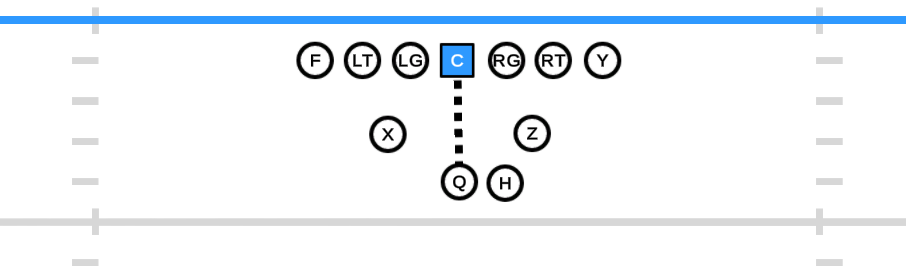

They placed tight ends next to the right and left tackles. They replaced the quarterback with a running back and placed another back next to him in shotgun four yards behind the center, a yard closer than is typical in their spread offense. The remaining two players became known as "knockers," a position the Marks' made up that aligns in the backfield inside the tackles and in front of the running backs. Their alignment leaves a window for the ball to be snapped.

The first staple play in earthquake was a power run. The "quarterback" received the snap and rode a fake to the running back. At the same time, the backside guard and tackle pulled to the playside. The frontside knocker was responsible for kicking out the edge player.

That action often created a convoy for the ball carrier to follow and more often than not in the early years that ball carrier was Will Knight. In Smyrna's three consecutive state title seasons, the earthquake formation, with power as its primary play, averaged 7.9 yards per play from scrimmage and had an 81% success rate as a 2-point attempt.

— Mike Judy (@coachmikejudy) January 31, 2023

Forging an identity

Tony and Mike are quick to point out that the success of the formation, as with any package, depends on the personnel.

"Obviously, we've been blessed over those years to have phenomenal players," Mike said.

Earthquake took a dip in effectiveness after Will Knight left and as it became more exposed, averaging 6.5 yards per play from scrimmage and leading to a 68% 2-point conversion rate in the three full seasons between Smyrna's 2017 and 2022 state titles.

The conversion rate was still well above the threshold needed to make the 2-point "gamble" worth it. If you assume your kicker will convert 90% of his extra-point attempts, you need to convert more than 45% of your 2-point attempts to make the expected points added greater.

In 2023, Smyrna converted 63% of their 2-point attempts.

Every year it's the responsibility of the Marks' and the Smyrna coaching staff to figure out the best ways to use their players. They make tweaks to earthquake and their spread offense season to season based on the capabilities of the boys returning.

The two players in the backfield in earthquake will always be the team's most explosive offensive threats. The rest of the formation is a hand-picked mix of offensive and defensive players.

They call the personnel package used for earthquake the special forces unit. They have their own practice time and film study during game weeks. The unit selects a certain type of athlete who is willing and able to fight in close quarters.

"It’s about how physical can you be when that dude is on top of you," Mike said.

In the five seasons before Judy took over the program, Smyrna had a combined record of 17-33. When Judy came in, he made a point of doing things that were out of the ordinary at the time. They ran an up-tempo, hurry-up offense, played 22 different starters and committed to going for 2 to the extent the team does not practice a field-goal operation.

The goal was to create an identity for the program that Smyrna players could find pride in and to maybe catch opponents off guard who were ready for 3 yards and a cloud of dust football.

"We needed to do something a little different," Judy said. "Not only to allow us to compete from a contrarian standpoint but to buy some time to develop players."

The systems Smyrna developed give responsibility to its athletes to communicate and make reads throughout the game. For example, in the spread offense, once a play is signaled in from the sideline the quarterback has to tell the offensive line the play call and adjust protection.

Yamir Knight, who this fall finished his first season at James Madison, felt ahead of many of his freshman teammates because of how detail-oriented Mike and the offensive coaching staff were.

He remembers watching his brother Will run earthquake without a clue of what was going on. By the end of his high school career, the coaching points of the formation were ingrained. He could play hard and fast.

"It's really like old-school smash-mouth football," Knight said.

Evolutions of earthquake

By the time Yamir came to Smyrna, Delaware defenses had already seen earthquake for several seasons and were starting to catch up. Simultaneously, Smyrna continued to see the benefits of using earthquake outside of 2-point conversions as a change of pace to its spread attack.

On multiple occasions, including the 2017 state title game played two days after a 4.1-magnitude earthquake shook the Dover area, it became Smyrna's primary offense in the open field not just at the goal line.

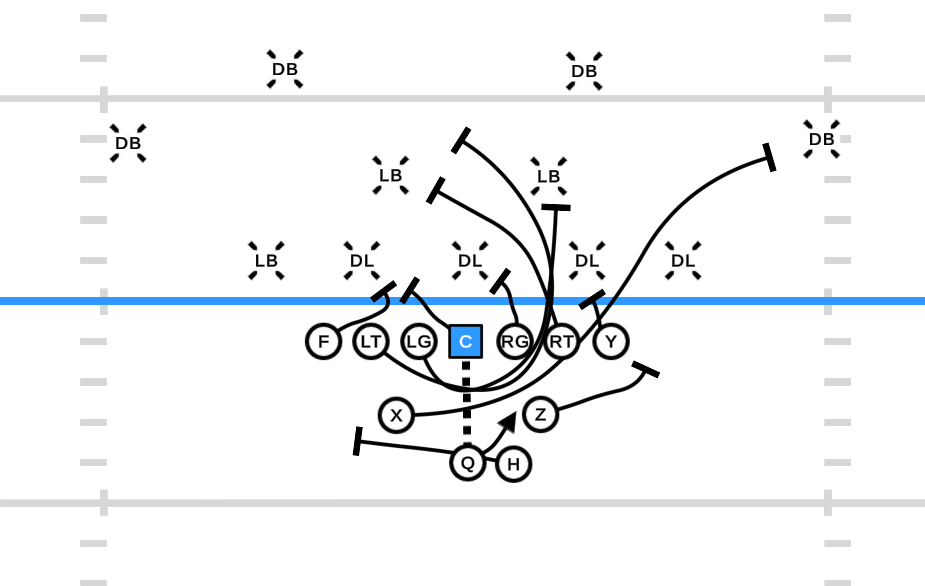

The next evolution was to expand the scope of earthquake to be able to stress the defense vertically and horizontally. In "cheetah," Tony and Mike introduced an option element. The frontside knocker takes the edge or "alley" defender in the direction he wants to go.

If the knocker kicks him out, the ball carrier redirects inside and runs off tackle. If the defender crashes inside and the knocker takes him that way, the ball carrier bounces to the outside with just the cornerback to beat.

Judy compares it to judo, a martial arts practice predicated on using opponents' momentum against them.

The play can be run in either direction without any change to the alignment because of another evolution in the package. The running backs align side by side in a sprinter stance and both present as though they are receiving the ball. The center snaps the ball between them. The backside running back (if the play is run right, the running back on the left) receives the snap and the frontside running back serves as a lead blocker.

"It evolved with a bit more finesse factor," Tony said.

They have also added pass plays, a counter handoff to a knocker and another power run to the package. When he's asked if he's concerned with opponents knowing how earthquake works because of his book, Tony shakes his head.

"It's not what we do," he said. "It's how we do it."

He added later, "That's what we did the last eight years. It's not necessarily what we're going to do next."

Kahmaj Kearney 5-yard TD out of the earthquake for Smyrna. Run fails for two.

Smyrna 6, Salesianum 0 7:57 1Q #delhs pic.twitter.com/K3qJrXKpLg— Tim Mastro (@Tim_Mastro) November 18, 2023

A football family

Tony played defensive back at Ithaca College from 1974 to 1976, then coached high school football in upstate New York for the next three decades. He spent 10 seasons as head coach at Elmira Southside High School, a public school 35 miles south of Ithaca. That's where Mike became a record-setting receiver in the late 1990s under his father's tutelage.

Mike played four seasons at Ithaca before launching into his own coaching career, first as a graduate assistant at UD and then as a high school coach.

"Every father dreams of an opportunity to be able to watch their son come up in their footsteps," Tony says with a slight shake in his voice. "Not many do. I've been incredibly blessed."

Tony is well-versed in the double wing — the system earthquake is most akin to — and credits Jim Butterfield, a three-time Division III national champion coach at Ithaca, with emphasizing to him the importance of winning in the "off tackle gap," which is where the earthquake formation often strikes.

Starting at UD under then offensive coordinator Kirk Ciarrocca, Mike was exposed to the spread, a newer wave of offensive thinking designed to make defenses cover the 53 and a third width of the field as well as the vertical passing game.

The combination of their backgrounds is reflected in Smyrna's offensive approach. It's the marriage of the earthquake power run game and the spread that they say is the key to their effectiveness. Some defenses are built to stop one. Few are built to stop both.

There are now three generations of the Marks family at the stadium on Friday nights and Saturday mornings. Mike's son Drew played some quarterback for Smyrna this fall as a freshman.

Tony is in Mike's headset throughout the game. He sits in the press box and tells Mike the down and distance as a play is whistled dead. He then describes the structure of the backend of the defense (middle field open or closed, single-high or two-high) and the box count ahead of the next snap.

Tony might give suggestions between sequences based on what he's seeing, but it's Mike's offense to call.

When it's time for earthquake, however, Tony calls the play.

"Unstoppable: Integrating the Earthquake Package into the Spread Offense" written by Tony and Mike Marks is available through Championship Productions

Contact Brandon Holveck at bholveck@delawareonline.com. Follow him on X and Instagram @holveck_brandon. Follow him on TikTok @bholveck.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: How Smyrna's earthquake formation has evolved through 4 title runs