The Road to Becoming a Yosemite Climber

This article originally appeared on Climbing

I was riding shotgun with Jon Frank at the wheel heading east past Barstow in 1981. I'd drifted into a slumber from the hot Mojave wind drumming through the open window of the '71 Volkswagen beetle, when I thought I heard something--a dry grinding, like a coffee mill without beans.

***

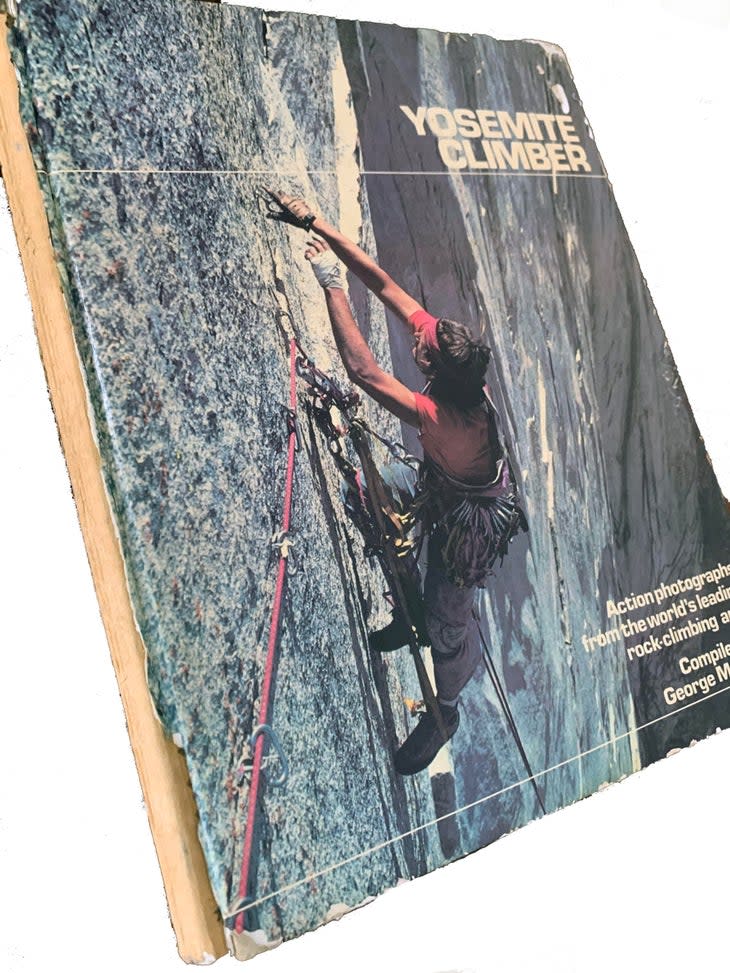

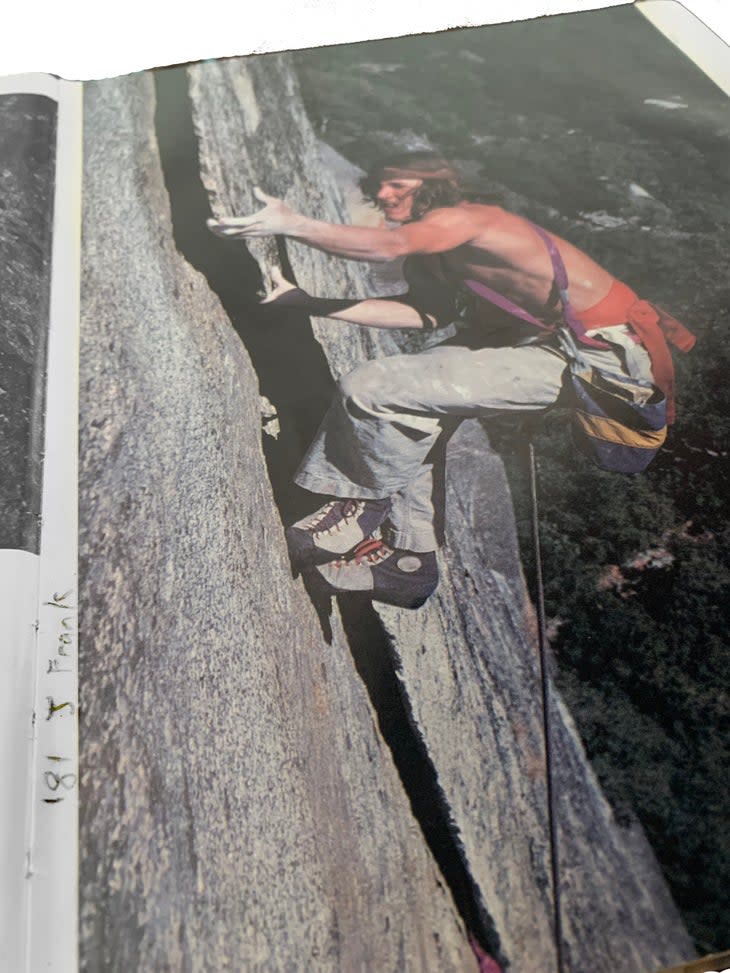

We had summered in the Valley, climbing as many routes as we could get up, gems chronicled in George Meyer's Yosemite Climber, the book, bible really, that revolutionized climbing photography and even climbing itself. When we first cracked that book open and gazed upon Dave Diegelman suspended under the horizontal roof of Separate Reality, one taped hand wrestled in the crack and the other yarding slack to clip a nut, well that was it. Our small circle of single-minded climbers included Mark Herndon, who would become one of BASE jumping's early protagonists and who now spends nights staring through lenses at distant stars, and Jimmy Ratzlaff, all 6-foot-2 of him and who would later become a preacher on the Front Range. And Sam Audrain, the coolest of the lot who attracted ladies like filings to a magnet. It was good just to be around him.

We grouped up in various vehicles and drove straight from Oklahoma to Yosemite, pulled there by the unseeable promise of a salvation only the rock can lay on you.

Camp 4, site 23, was a patch of dust and pine needles and with a leaning picnic table decorated with initials and names and years. The site smelled of old camp smoke, sap, and something worse when the breeze across the nearby restrooms was unfavorable. We pitched tent and in the days that followed worked our way through the book. It was a point of pride, or personal growth, when we got in the same positions on the same routes as in Yosemite Climber. Sometimes I'd pause on an especially satisfying move and let the vibes really vibrate in.

In pencil in the book margins I noted what we'd done in case I'd later forget. You could never forget Outer Limits, Wheat Thin, 10.96, Bircheff-Williams, The Good Book ... but it would take me a lifetime to realize that.

Back in June, before we'd gone off to Yosemite Jon and I had purchased a car, a red VW beetle. It was already dented and a decade old, but its $250 price tag fit our pocketbook if we split it 50/50.

The bug ran smooth enough, and we had no reason to question its mechanics. We just had to top off the oil and never let the 60 horsepower air-cooled engine get too hot, which meant governing the speed to no more than 55 mph--coincidentally the national speed limit that year. We also needed to take care and keep the rpms to a minimum on the 4-speed. Don't ever let the tach needle get in the red.

I've ridden lawn mowers with more zip than that bug, but it delivered us to Yosemite and puttered us around there, out to the Cookie and back. We were always mindful of the oil and rpms and tried to always park it nosed downhill in case the battery died and we had to roll start it. In August we had to head home and to school. Jon and I planned to drive straight through, day and night, swapping out the wheel while the other of us tried to recuperate. I've never ridden in a WWII sub, but I imagine it was a bit like being in that bug: tight, hot, loud, smelled of oil and gas and burning belts.

The trunk in the front of the bug swallowed our bulging haul bags of climbing gear: rigid-stemmed Friends, nuts, several hundred carabiners, enough iron to anchor a small ship, ropes, a portaledge. The back seat was jammed up with camping gear and clothing, canned goods and a couple of jugs of water we'd swig in the summer in a car without any air. If we hadn't been so skinny there wouldn't have been enough room for us in the car.

***

The rattle woke me. At first a distant sound I couldn't understand. Slowly it came into clarity, and I woke from my heat-drunk sleep. I checked our speed. 55, good. No oil light on. Good. Then what?

The noise seemed to come from our car, but maybe it was from outside and was being thrown our way like how a ventriloquist messes with you.

But there was nothing outside but brush and the blazing sun.

I looked again at the instruments. The tach needle was in the red, laying all the way over as if it had fallen and couldn't get up.

"How long have you been in third gear on I-40?" I asked Jon.

"What, there's four gears?" he replied.

Jon slid the stick into fourth and the engine calmed like a baby on a bottle.

I pushed my feet against the floorboards to stretch, and was nodding off again when the engine threw a screen of thick smoke down the interstate. All the dash warning lights blinked on. Jon coasted to the shoulder as traffic braked and swerved, blinded by the greasy smoke.

The car was done, that was sure. It wouldn't turn over, and once the cloud had cleared and the threat of an explosion seemed to pass, we popped the hood. The little German engine looked as if it had gone through a re-entry.

Getting a tow to a repair shop was beyond our means. Between the two of us we'd left the Valley with just enough cash for gas, maybe a bit extra for cold drinks if we got a tailwind to improve mileage.

"What's next?" we asked each other.

"We'll have to hitch home."

We were 1,215 miles from home and the odds of anyone picking us up, two guys with a heap of bags, were slim.

Jon and I took turns thumbing on the shoulder as interstate traffic blasted us with waves of heat and fumes. To improve our odds, the one of us who didn't have his thumb up hid in the tall weeds--a car is more likely to stop for one than two, especially if those two looked liked they'd escaped from incarceration.

Standing on the asphalt in the Mojave desert in summer was only slightly cooler than walking on coals, but we had food and water for several days and were used to some heat on Yosemite's glorious walls, plus we were used to Oklahoma's summer hellscape.

No one stopped for us the first day, and as the sun dipped behind the shimmering horizon we humped our pads and bags about 100 feet from the bug and laid down in a depression, hidden from the road in case a Ted Bundy sort happened by.

No one stopped the second day, either, and as our water ran low--Barstow recorded 110 degrees for three consecutive days, the hottest of the year--our youthful unconcern began to waver.

That evening, as the blacktop popped and cooled, a red convertible pulled up behind our bug. The ride's top was down revealing a white interior and an even more revealing blonde in a low-cut top, eyes shaded by a pair of large sunglasses. Jon dropped his thumb and dashed over.

Jon is one of the most naturally powerful climbers I've known. With an upper body like a front-end loader and sandy blonde hair to his shoulders, he looked like he belonged in SoCal, and in fact that's where he eventually went.

"I saw you here yesterday," said the woman, "and I said to myself that if you were still here the next day I'd pick you up."

Hearing this I rose from the bushes.

"Oh, there's two of you," said the blonde. "You boys grab your stuff."

This is our lucky day, I thought. Absolutely. I gave Jon the thumbs up, and grabbed the straps on our haulbags.

"No thanks, mam," Jon said practically immediately. "We won't be needing a ride, we're good right here. Appreciate it, though."

Jon was and remains a solid Christian. Getting a ride in these circumstances with an opposite member wasn't in his Psalms. About a year earlier we had been riding in his land shark cruiser, an old Oldsmobile type with a truck so large Jon slept in it, when Sympathy For The Devil by the Stones began playing on the 8-track. "Please allow me to introduce myself ..."

"Noo!" Jon had screamed before ejecting the tape and throwing it out the window.

The situation we were in now was a similar evil.

"You sure about the ride?" asked the woman.

Jon was sure. We settled back into the brush for another night in the hard desert.

Propped up on our haulbags, we gazed at the distant glow of Barstow.

"Imagine," said Jon, "if we ever do get a ride we can't just leave the car here, can we?"

"Let's burn it," I said. "We'll strip off the plates and VIN so it can't be traced to us, then put a rag in the tank and light it.

We had just finished unbolting the plates and popping the VIN off with a knife when a highway patrol stopped. We scurried into the brush. Did he see us? At this point we couldn't ask for help--how would we explain the missing tag and VIN?

The patrolman put his spotlight on the bug, then his radio cackled and he sped off.

"We can burn it in the morning," I said to Jon.

The third day was another scorcher, and we again resumed duty trading shifts on the shoulder.

"How long do you think we can do this?"

"Until we become skeletons."

About 5:30 that evening a pickup stopped.

"You want to sell your VW? I restore old bugs," said the driver.

When he offered us $150 Jon must have thought an angel had descended. I even almost thought so. The money was just enough for bus tickets home, and we still had wall food so chow wouldn't be an issue.

"I'll be back in the morning with the money, and I'll give you guys a lift to Barstow."

We hopped in his truck the next morning. In Barstow, we wrestled our haulbags into the belly of a Greyhound, then settled in with the rest of the flotsam for the 30-hour ride home.

The bus station in Weatherford, Oklahoma, was about a mile and a half from my parent's house. It was even hotter there than in the Mojave, and a stiff wind bent the trees to the north as if to point to more hospitable lands.

I was too beat to carry my bags any distance, and shuffled over to a payphone outside the depot.

I hadn't talked to my parents in nearly three months, ever since Jon and I pulled out of the driveway in that bug. I'd sent a postcard, something like "Yosemite is great," but that was the extent of communication and that's how it was done back then. You left and came back and the middle was just details.

In the 1800s some of my dad's ancestral clan left Kentucky, going west for new promises. The Kentucky Raleighs never heard from the "went-west Raleighs" again until just a few years ago when my dad looked them up in Breathitt County, Kentucky, a county infamous for blood feuds, and contacted them.

"We thought y'all had been killed by Indians," they said, "good to hear from you in any case."

Not that much had changed in the family concerning verbiage when I called home for a ride.

"Hi Mom, can you pick me up, I'm at the bus station here in town."

"We're having lunch. I'll be down once your Dad's done eating," said Mom.

"Thanks," I said, "and can you bring a dime, I had to borrow one for the phone."

I dragged my bags into the shade, found a spot out of the wind, sat on them, and waited.

Also Read

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.