Ripcord: A Story of Fame, Love, and Tragedy

This article originally appeared on Climbing

This feature first appeared in ASCENT 2013. This updated version has been excerpted from Rogue's Atlas: 66 Flash Fiction Stories. Author John Long, Stonemaster, has written over 40 books, with nearly three million copies in print.

Yosemite Valley. Dawn. Mike Lechlinski and I are just stirring in our hammocks, lashed high on the granite face of El Capitan, when a whooshing sound shatters the silence. Louder, closer, building to a roar. Rockfall. Heading right for us: we're dead. I instinctively brace for impact as two BASE jumpers streak over our heads at 120 miles per hour. It seems impossible that two falling bodies can make such terrifying, ear-splitting racket, like God is ripping the sky in half with his bare hands. We scream, craning our heads from our hammocks, our eyes following the jumpers plunging into the void. Their arms dovetail back as they track away from the cliff. The pop of their chutes fires up the wall like shotgun blasts. They swoop over treetops and land 50 feet into the meadow as a beater station wagon screeches to a stop on the loop road. The jumpers bundle their canopies, jog over, and dive into the beater, which quickly drives off. This last bit looks sped up, like a Roadrunner cartoon. If the rangers catch them in the act, they're going to jail. We howl because we're still there, still alive.

"I think I pissed myself," says Mike. On a scale of one to a shitload, this sixty-second lark is off the chart.

In 1984, the adventure world caught fire and every serious player tried to blaze like hell. From our first sorties free climbing big walls to jungleering across Oceania, the mantra never changed: capture the burning flag. Our cousins in big wave surfing, kayaking, cave diving, and mountain biking were also charging hard, and we watched our group fever trigger the adventure-sport revolution. And the most visually dramatic show of them all was BASE jumping, the acronym for parachuting from a Building, Antenna, Span (bridge), and the Earth (cliffs).

A couple years after my close encounter on El Cap, I needed something bold to gain traction in the TV business, where I hoped to quickly score the trophy girls and crazy money. I was two months out of school, with a fistful of so-what degrees and a junker Volkswagen Beetle, determined to leave Yosemite behind. But secretly I didn't so much wave at the train as grab for it, afraid of getting left behind.

British talk show maven and future Richard Nixon interviewer, David Frost, had a boutique production house with Sunset Boulevard offices. I hired on as a writer and associate producer, knowing zero about the television racket. The salary didn't dazzle but my future glowed. We had several hour-long Guinness Book of World Records specials that we needed to style out with electrifying content. Previous episodes featured a dull parade of magicians, carnivorous spiders, and an English mastiff named Claudius, the world's largest dog. I promised to hose out the dog shit, clean up the show, and boost the numbers. I knew going in that staging world-class adventures for television was sketchy, but so what. I was handy with danger and eager to debut BASE jumping on primetime national television. The plan felt like money. That left the tricky bit: collaring someone to do the jumping.

My immediate boss, Ian, smooth, sardonic, and classically educated at Eton, favored exciting acts. BASE jumping was one of several adventure pursuits, each riskier than the last, that I'd scribbled onto our dance card, and which the network, indemnified of responsibility, could promote to the moon. Ratings were everything, but in Jack Daniels moments Ian sometimes asked, "We're not going to get anyone killed doing this, are we?"

"Not if I can help it," I'd say.

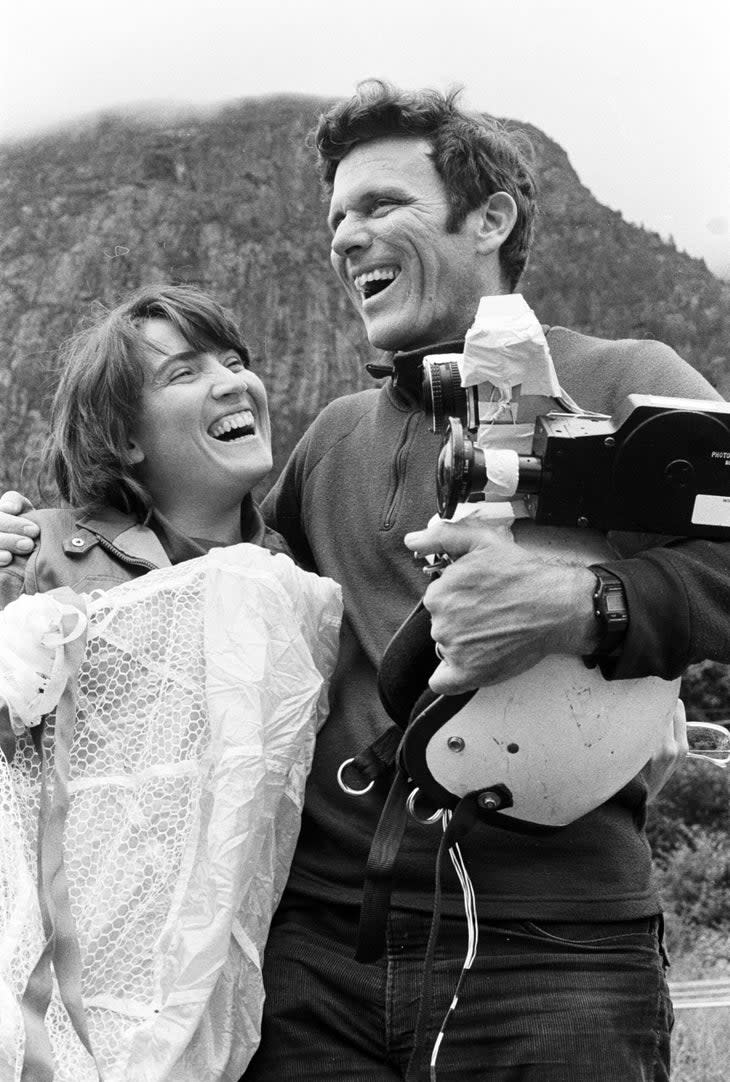

The stars aligned and, in late June, I flew to London and joined Carl Boenish and his wife, Jean. Carl, 43, later dubbed "the father of BASE jumping," was a free-fall cinematographer who, in the 1970s, had filmed the inaugural jumps from El Capitan, plus many other "first exits" off high-rise buildings, antennas, and bridges. For sheer burn and ebullience, Carl had few peers. Jean, nineteen years Carl's junior, brainy, wholesome, and distant as polar ice, lived her life in a language I didn't understand.

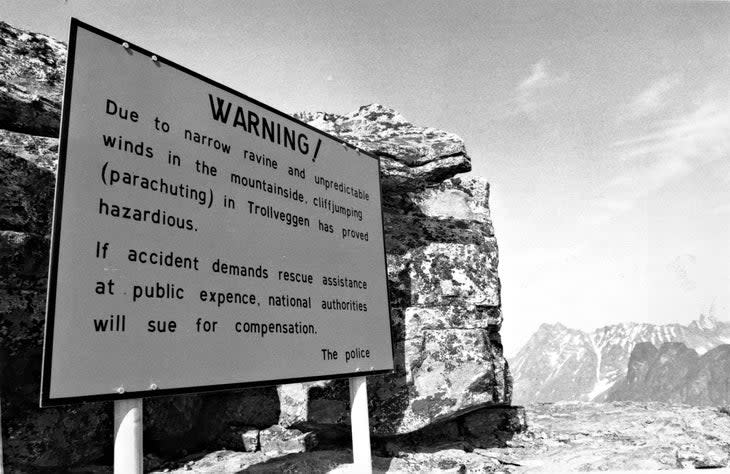

From London, Carl, Jean, and I flew to Oslo. The Norwegian airlines had gone on strike, so we packed six duffel bags into a rental station wagon and headed for the Troll Peaks in the Romsdalen valley, eight hours north. The narrow road meandered through still green valleys, dark as tourmaline, laced with alpine streams and glinting under the midnight sun. We stopped for beers at an inn (ginger ale for the Boenishes, who took no liquor), and I marveled at the year, 1509, chiseled on the stone hearth. Finally, we crept into the sleepy town of Andalsnes, surrounded by misty cliffs, including the Trollveggen, Europe's tallest vertical rock face, a brooding gneiss hulk featuring several notorious rock climbs and the proposed site for our world-record BASE jump. "Built when the mountain was built," folklore says of Andalsnes.

Carl and I breakfasted on pickled cod, peanut butter, and black coffee, and zigzagged up a steep road to the highest path and set out on a leg-busting trudge for Trollveggen's summit. We were joined by Fred Husoy, a young local, among the finest adventure climbers in Europe, who knew the Troll massif by heart--critical in locating our jump site. We shouldered packs and trudged over shifty moraines toward a snowy col.

The first few miles climbed a glacial plateau, broken occasionally by lichen-flecked boulders and gray snow drifts that never melted, carved by wind into gargoyles and labyrinths. The lunar emptiness hadn't changed in a billion years, and held the silence of the dead when the wind died down. It was so big and so blinding that even the birds felt lost in it, how they'd break the stillness and cry out. An elegiac keening that climbed to the ridgeline and broke. Another bird would answer. But the birds were not lonesome for each other. It was bigger than that.

From the moment we'd hit the trail, Carl hiked so slowly that I finally took his pack; but halfway over the big white plane, he once more had fallen well behind. Fred pulled on his raincoat against the drizzle, warning we had to hike faster or get blown off the mountain by afternoon storms. We slogged ankle-deep through a snowfield. When Carl caught up, wet clouds draped everything. No coaxing could make him hike faster. A little stone hut twenty minutes shy of the summit ridge offered a welcome roof from the shower. Carl limped in, collapsed, and pulled up a pant leg. Fred and I stared. Right above the ankle, Carl's femur took a shocking jag, as if he'd snapped it in half and the bone had healed inches off plumb. I felt small and mean to have pushed him. How did a person hike at all with a leg like that?

"Jesus. When did that happen?" I asked. He'd shattered his leg in a hang-gliding accident several years back, said Carl, who clenched his way through a wonky exposition on natural healing.

"I don't know, Carl," I said. "A bone doc could surely fix that. It's hideous." Carl swished the air with his hand. Who needed doctors when God Almighty would set things right?

His fingers trembled as he pulled up his sock. It felt incredible and reckless to stake my future on a man living off stardust and voodoo.

A week before, we'd organized the venture at Carl's house in Hawthorne, a small, L.A. suburb. From the moment I stepped through the door, Jean eyed me with steely reckoning, as though if she glanced away I might pilfer the china. Her clothes looked Mennonite-plain, the house, immaculate, all cups and chairs and handcuffs in their place. Nothing admitted she and Carl dove off cliffs for a living. As Carl raked through his garage, overflowing with gear, he'd bloviate about St. Peter, Coco Joe, or whoever. Without warning, Carl would dash to his piano and butcher some Brahms or Brubeck, then jump back into conversation, randomly ranging from electrical engineering to terracotta sculpture to trampolines and particle physics, galvanized by a screwy amalgam of new age doctrine and personal revelations. Often, he would heave all this out in the same sprawling rant. Ian thought he'd dropped acid. But Carl laughed so loud and burned so hot I found myself giddy by the inspired way he met the world. We lived in different keys, but we both craved the intimacy of risk. And in the fellowship of adventurers, folks like Carl Boenish drove the bus.

Outside our little stone hut in the Troll Peaks, the shower slacked off and we continued over snowy slabs toward the mile-long summit ridge, all dark clefts, precarious boxcar blocks, and pinnacles digging into the sky, so twisted and multidimensional, M.C. Escher couldn't have drawn it in his dreams. The wall dropped 6,000 feet directly off the ridge and into the Trondheim valley. The rubbly slabs angled down behind us to the high glacial plateau, where perpetual snow framed a tiny lake glowing aquamarine. Black-and-white clouds gathered, masking the ridge, cutting visibility to several hundred feet and making it difficult to navigate. Without Fred's knowledge of the labyrinthine summit backbone, we would have wandered blind. The clouds parted and we lay belly-down on the brink, sticking our heads out over the immediate, sucking drop. Carl rubbed his leg, laughed, grimaced, and laid out his requirements.

The wall directly beneath his launch must overhang for hundreds of feet, he said, long enough for a plunging BASE jumper to reach near-terminal velocity. Only at top speed, when the air became thick as water, could his layout positioning create enough horizontal draft to track and fly out and away from the wall (the now-ubiquitous wingsuit wouldn't be invented for another dozen years) to pop the chute, as Mike and I had witnessed on El Capitan. The new parachutes didn't simply drop vertically, but sported a three-to-one glide ratio--three feet forward for one foot down. But twisted lines could sometimes deploy a chute backwards, wrenching the jumper around and into the cliff.

"Here, that would be fatal," said Carl with buggy eyes, peering back over the lip.

The most prominent spires along the ridgeline were named after chess pieces. Out left loomed The Castle, a striking, 200-foot-high spire canting off the brink like the Tower of Pisa. An exit from the summit, hanging out over oblivion like that, had to be safer than leaping straight off the summit ridge, making it an obvious feature to scout.

Carl hung back as Fred and I tied on a rope and scrambled up the water-logged Castle to the top--a flat and shattered parapet, perfect to start our rock tests. We wobbled a chair-sized boulder over to the lip and shoved it off. Five, six . . . Bam--a sound like mortar fire. Debris rattled down for ages.

"No good," said Carl, yelling from the ridgeline. "Way too soon to impact." We tried again. This time, I leaned over the lip and watched a second rock whiz downward, swallowed in fog 300 feet below. Three, four . . . Bam! My head snapped up. There had to be jutting ledges mere feet below the fog line. We shoved off more rocks and kept hearing the immediate, violent impact of stone on stone. "Forget it," Carl yelled. "The Castle will never do. It'd be crazy." The flinty smell of shattered rock wafted up as Fred and I rappelled off the pinnacle and joined Carl.

For another hour we continued with the rock tests, at successive points along the rubbly brink. Trundling rocks off most any other cliff could kill people. Not there. Any climbers on the wall and we'd have known about them. And below the towering upper wall spilled a massive, low-angled slab, terminating in a sprawling moraine field where nobody but climbers had reason to go. The menace, though huge, was strictly our own. All around us loomed forces and forms so elemental they had never organized into life, so nothing native to this place could even die. But we could. That's what made it so heady to try and sort this out. But each rock we shouldered off dashed the wall within seconds. Lightning cracked off the lower ridge and we ran for the valley. Carl hobbled behind.

Norwegians are a handsome race, normally demure, until you pull the cork on Friday afternoon and the dritt hits the vifte. That night, all the young locals in town crammed into the pub in the hotel's basement, where we drank Frydenlund like mad, chased it with beer, and danced to The Who. Several gallons in, a tall brunette with a stylish bob grabbed a handful of my shirt. She acted more curious than courageous, and couldn't find the words. So I trotted out the one Norwegian phrase I had memorized from a handbook in my room: "Hvorkanjegkjope en vikinghjelm?" (Where can I purchase a Viking helmet?)

"Are you a Viking?" she asked in flawless English. I said I'd try to be one for her, and she said, "You will marry me." That night I saw eternity and it looked like this: a girl and a boy dancing in a crowd on an unswept floor in a bar on a thousand-year-old street.

Aud came from the next town over, and worked some dreary retail job in Andalsnes during summer break from nursing school. We spent our free time together, and I learned there are moments where nothing is so grim as being alone. I usually went it alone, a shark who survived by staying in motion. Until Aud drew the restlessness from me like a thorn, and light leaked through a soul cracked open. Over the next month, as we got the jump site dialed and waited for good weather, I was either with Aud or imagining her.

The next day, as Carl recovered in his hotel room, Fred and I slogged back to the summit ridge for our first of many recons, trying to locate a viable launch site. The existing world's longest BASE jump, first established three years before, exited the ridge well east and some 400 feet lower than the Castle. That left us to scour the chaotic, quarter-mile-long ridge between The Castle and the old site--a confusing task for sure. Over the following weeks, when we weren't kicking around the Trollveggen's cloudy ramparts, Fred and I would snag Aud and go bouldering on huge, mossy erratics, or hike up spectacular peaks or along jagged ridges snaking through the sky. I was 26; Fred and Aud were in their early 20s, all of us novice adults, searching for where we fit into the world. For a weightless moment, we shared an enchantment. Twice more, Fred and I explored the summit ridge, ever dashed by hailstorms.

The rain, meanwhile, kept washing our budget into the talus, and my inability to locate a jump site was wearing us out. Norway completed our production schedule, and the crew looked toward holidays in Paris, the Greek Islands, or home. We had to get this done. On the ninth scout, after a nasty piece of scrambling and several tension traverses on crappy rock, we located the highest possible exit from the ridge: The Bishop, to use the old chess name. But again, we got weathered off before we made our rock tests. We returned early the next day and, lucky for us, the sky shone all blue distance, the entire ridge fantastically visible and spilling down on both sides for miles. After weeks spent wandering about in the fog, it felt like a vision from the Bible, the entire rambling cordillera unmasked before us. We definitely were on the apex, walking unroped on an anvil-flat, 10-by-50-foot ledge that terminated in an abyss as sudden and arresting as the lip of the Grand Canyon. If the rock tests checked out, we were halfway home. The easy half.

I lashed myself taut to two separate lines, bent over the drop, and lobbed off a bowling-ball-sized rock while Fred timed the free fall. The rock accelerated ferociously and dropped clean from sight. Twelve, thirteen . . . I glanced over at Fred and smiled. This could be it. Seventeen, eighteen . . . BANG! A faint puff of white smoke appeared thousands of feet below. That rock had just free-fallen three quarters of a mile. No question, The Bishop was our record site. Fred pointed out the original launch spot (or exit site), still far left and 300-something feet below. I chucked another rock and we watched it shrink to a pea and burst like a sneeze near the base, the echo volleying up from the amphitheater. I tried to imagine strapping on a chute and plunging off, but couldn't. And I couldn't yet imagine ever climbing this towering heap.

From a distance, Trollveggen looked classic, a 2,000-foot-high talus slope topped by a 3,600-foot rock wall. At its steepest, the summit ridge overhung the base by 160 feet. Up close, however, the greatest rock wall in Europe was all fractured statuary, a vertical rubble pile top to bottom. And so utterly, unspeakably other, neither alive nor dead. It simply was, somehow, and it spooked me more by the day and the week.

We ascended our fixed rope, reversed the traverse and, as the first raindrops fell, Fred and I hoofed it to the valley with the good news.

For the next five days, Aud, Fred, and I stayed glued to the Oslo news channel, frequently stepping outside and glancing through thundershowers for some providential patch of blue. Mostly we milled around the production HQ in the hotel basement, living off chocolate scones and espresso. Helicopters stood on standby, film cameras were loaded, every angle reckoned, logistics planned to the minute. Meanwhile, journalists throughout Scandinavia streamed into Andalsnes. The local paper ran full-page spreads in a town where the breaking news trended toward a farmer hooking a record lunker in a secret stream. When approached and pried at, Carl would laugh and let fly his exotic babbling as journalists nodded and smiled but took no notes. Finally, Jean--normally so laconic she might have been mute--would answer with several cold facts and figures.

A celebrated Oslo stringer, newly arrived, cited previous BASE jumping accidents and questioned something that had every official chewing their nails. As starry-eyed admirers gathered to touch Carl's jumpsuit, she all but screamed that the emperor had no clothes. The glossy hype and big money spent was nothing but a made-for-TV flim-flam in the service of a maniac who, by the sound of him, had flunked kindergarten and had little regard for his own safety. The worry on her face and edge in her words betrayed her annoyance that The Jump had a gravity even she couldn't escape. None of this was simple.

We slunk around. Rain fell in sheets. Tension mounted. With all the media hoopla, all the delays, each emerging detail raised the story's sails sky-high. Norwegian television ran nightly updates. The big Oslo station sent a video truck. With a week's momentum, the production took on the pomp and blather of Hollywood--precisely what I'd hoped to avoid.

Several journalists took to quoting Carl directly. The translation to Norwegian vexed ("like Ted Hughes on peyote," Ian suggested), the waiting game somewhat relieved by trying to guess what the hell Carl had said. The sky growled at us. Scandinavia stood by. Each day in limbo meant thousands of dollars lost to feed, liquor, and house the crew. This quickly morphed into an impatience for what required steadfast deliberation. Throughout, the Boenishes were ready to jump. At 8 p.m., July 5, 1984, the weather broke.

Everyone scrambled, desperate to shoot something, even in bad light. In two hours, cameramen choppered into position. The helicopter dumped Carl, Jean, Fred, and me into a small notch 40 feet from the launch site on The Bishop. This avoided having to wheedle the Boenishes across the traverses, fitted with fixed ropes, that had given Fred and me fits owing to loose rock. Carl pulled on his flaming red jumpsuit and paced around like someone waiting for the electric chair. Jean began assiduously studying the launch site. I pitched off a rock that whistled into the night. Other rocks followed to verify my estimates, but disclosed another hazard.

"Sure, they drop forever," laughed Carl, "and that's a good thing. But they're never more than ten feet from the wall." That left no margin for error. If they couldn't stick the perfect, horizontal free-fall position, if they carved the air even slightly back-tilted--head higher than feet--they could possibly track backwards. Carl demonstrated with his hands, one hand as the wall, the other for the jumper. When his hands smacked together, Fred and I jumped. Jean, cool as the Romsdal Fjord, rolled more stones toward the lip. The light faded to a gray pall. Far below, the great stone amphitheater swallowed the night.

The radio coughed out: "Come on, mate, let's get on with it!" The crew was freezing and the director of photography feared it would quickly get too dark to film.

"Hey," said Carl, lucid as water, "I can't be rushed to jump off this cliff, screaming past those ledges at midnight." I quoted this word-for-word into the radio, and the crew backed off. They'd planned to jump in tandem--Jean first, followed closely by Carl--but for this run-through, Carl chose to huck a solo jump while the cameramen previewed and assessed the angles. The sun, at the wee hours, was too dim for full glory, but a practice jump could help the cameramen dial in the details. The sky, though darkening, remained clear and flawless so, with some luck, the good weather might hold. After Carl's trial jump, we'd resume in a few hours, when full light returned.

Carl strapped on his parachute and I tried to capture his kinetic energy on film. But I couldn't pull a focus in the gloom. I packed away the Ariflex, grabbed a still camera, and turned to the drama before the jump.

"Ten minutes," said Carl, bug-eyed, jaw working, hands fidgety. Jean helped Carl with the last straps. Cued by days of front-page spreads, the road below swarmed with cars and people, headlights winking in 1 a.m. gloom.

"Five minutes," said Carl.

He pulled some streamers from his pack. Leaning off the ropes, I lobbed them off. No wind. They fell straight toward the base, shrinking to a blur. Everything looked go.

"One minute," said Carl, his voice high and tight. He cinched his helmet and slid twitching fingers into white gloves. I pitched off a final rock and Carl tracked it, visualizing his line.

"Fifteen seconds."

Carl unclipped the rope and stepped over to the lip. Horns sounded below. I was tied off to several ropes, my feet on the edge, with a panoramic view for the ages.

Carl's shoes tapped like a rhythm machine, eyes unfocused. He started his countdown, which Fred mimicked into the radio: "Four, three, two, one!" And he was off. Watching someone jump straight off a cliff like this is so counterintuitive to a climber's instincts that Carl might as well have jumped into the next world. The void swallowed him alive, his streaking form more easily imagined than described. The air froze in my chest.

After a few seconds, Carl's arms went out to stabilize, his legs bending and straightening while his jumpsuit whipped like a flag. With roaring speed, Carl passed several ledges with 10 feet to spare, body whooshing, ripping the air with a violent report. After 1,000 feet, his arms snapped to his sides as he flew horizontally away from the wall, tracking 50, 100, 150 feet, at 120 miles per hour, a swooping red dot. Thirteen seconds, fourteen, fifteen . . . Pop! His yellow chute unfurled big as a circus tent, and he glided down, over the slab and moraine field to the meadow. The picture-perfect jump.

Fred and I crabbed back from the lip, gaped at each other, and howled. Some called Carl an idiot for risking his life over something that didn't matter; but we'd just watched him rogue fear with imagination, and dive into the unknown. And if that doesn't matter, nothing much does.

Back at the hotel at 3:30 a.m., the chaotic crews, gnashing producers, frantic journalists, film loaders, battery chargers, pilots, and hangers-on, all guzzled espresso and ducked out to check for clouds, everyone anxious to film the jump and clear out. A chartered jet sat gassed and awaiting the crew once we finished filming, hopefully by noon. At 4 a.m., I laid down with Aud for a short nap, but couldn't settle for all the caffeine and apprehension.

At 6 a.m., two helicopters ground up through Persian blue skies and deposited us on The Bishop. Half an hour later, after some rock tests, and rechecking their rigs, the laces on their shoes, the film and batteries in their helmet-mounted cameras, Jean tiptoed to the lip, with Carl inches behind her. I stood five feet away, lashed to a rope, toes curled over the brink, shouldering a 16 mm film camera. 100 feet straight out in space, the helicopter yawed and hovered like a dragonfly. Fred gave the order to roll cameras. The Boenishes stepped off the lip and dropped into the void. Jean later wrote:

Eyes fixed on the horizon, I raise my arms into a good exit position. Then from behind, 'Three! Two! One!' For an instant my eyes dart down to reaffirm one solid step before the open air. Go! One lunging step forward and I'm off, Carl right on my heels. Freedom! Silence accelerates into the rushing sound as my body rolls forward. I quickly realize that the last downward glance has been an indulgence now taking its toll, for I roll past the prone into a head-down dive, which takes me too close to the wall. The first ledge is rushing towards me as I strain to keep from flipping over onto my back.

Through the viewfinder I watched Jean dive-bomb and slowly cant over onto her back. I panicked and ripped away the camera as she plummeted, her toes nearly brushing the first ledge.

"Holy shit!" Fred yelled.

Jean somehow arched back to prone, her hands came back, and the duo swooped away from the wall, shrinking to colorful specks, still flying, 200 feet out, still free-falling.

Their training, from thousands of skydives and hundreds of BASE jumps, steered them down the face. But watching the pair, as they streaked toward hungry boulders, stopped my heart.

"Pull the chute!" I screamed. Sixteen seconds, seventeen: POP! POP! A world record, no injuries. Cameramen raved over the radios. Newsmen and bystanders swarmed the Boenishes after their pinpoint landing. The world toppled off our shoulders.

Fred and I were done, and drained. Nothing but smiles, chocolate strawberries, and champagne back at the hotel. Ian and I both thought we had a shot at an Emmy with this one, and my career in television glowed. Aside from the delays, the jump had gone exactly as planned, but the crew scrambled to pack and leave on the charter. Ian was so worried about an accident that he rushed to clear out lest something happen retroactively. That afternoon the charter jetted for London, and those left behind, including half the kids in Andalsnes, moved to the bar in the hotel basement, where several storylines began to converge. I could never have guessed where this junket was about to take us.

A Norwegian named Stein Gabrielsen and his fellow countryman Eric (last name unknown) had arrived in Andalsnes only hours before. I met them in the bar, thinking they were another two Euro BASE jumpers drawn there by the big news, now splashed across Europe. In fact, while Fred, Carl, and I had begun scouting Trollveggen's summit ridge, Stein and Eric (both working in America, and unaware of our plans) had purchased one-way tickets to Norway to attempt the world-record jump off the Troll Wall, something they'd planned for three years. They would have gotten the record, too, except they'd gone on a ten-day bender the moment they met with friends in Oslo. When a girl showed Stein the newspaper story about how Carl and Jean were already in Andalsnes, waiting for the clouds to lift, he and Eric bolted directly, arriving in town late that evening.

They walked to the base of the Troll Wall, still glowing under the midnight sun, both men eager to scope out their record site. That's where they met "a drunk old Norwegian dude" who pointed at the dark cliffs and said, "That is the Devil's mountain." They walked back to town and spent their last krone on beer at the pub, where several dozen of us were finishing our wrap party, a Hollywood tradition. I remained the final holdover from the American production crew, there to settle accounts and hang with Aud. Stein and Eric, both flat broke, joined the bash only to learn the Boenishes had scooped them by a few hours. At best, they might repeat the record--the adventure-sports version of an asphalt cigar. Their consolation was the $500 of production money I had left to blow on booze.

"Eric and I found Carl," said Stein, "congratulated him, and asked about his launch site." Carl said he jumped from The Bishop. Stein had surveyed the ridge and believed The Castle stood higher. "Check a chess set," said Carl. "The Bishop is always taller than The Castle." "Either way," said Stein, "Eric and I are jumping The Castle tomorrow."

"Carl became visibly nervous," Stein later wrote, "and suggested we meet at their hotel for breakfast next morning, around 10 a.m. Then we could go jump together." A free meal sounded good, so Stein and Eric agreed. We closed the bar and half-mashed on Aquavit; Aud and I staggered to her apartment and I passed out for twelve hours.

The following morning, Stein and Eric met Jean at the hotel. Jean said Carl was in town, arranging their travel back to the States, and she invited the pair to breakfast. An hour passed and still no Carl. Jean kept glancing at her watch, out at the driveway, back at the map of Trollveggen hanging on the wall. Jean said she was sorry. She'd deceived them. Carl had been afraid they would usurp his record (as The Castle is higher on the ridgeline than Carl and Jean's launch site on The Bishop), so he'd left at sunrise to go jump The Castle. Jean figured he had already jumped and was at the landing field, waiting for a ride. She suggested Stein and Eric take the rental Volvo, snag Carl, and head back up to The Castle for round two. Jean needed to pack. Stein and Eric had gotten snookered and sent to fetch the culprit. One can imagine their conversation as they drove to the landing zone in the big meadow, to talk things through with Carl Boenish.

Back at Aud's apartment, I sorted gear for a one-day, racehorse ascent of the Troll Wall. I'd changed my mind a hundred times, but couldn't blow off Europe's biggest cliff when it was right down the road. A quick rap on Aud's door. It flew open and Fred rushed in.

"Carl's been in an accident," he said, "and it looks bad." A car accident? No, said Fred. Early that morning, Carl had hiked back up to Trollveggen and jumped off The Castle. That couldn't be right. After the last two days tromping around, Carl would be resting his bum leg for sure. Our production had caused such a stir that, for going on a week, jumpers like Stein and Eric continued streaming in from Sweden, Iceland, Denmark, and beyond. Any accident was theirs, I said, not Carl's. Fred shook his head. Carl had enlisted two teenage brothers, both local climbers, to hike him up. One, Arnstein Myskja, had witnessed Carl's accident and stood there next to Fred, trembling in his boots.

Ten minutes later, I was dashing across peat bogs, seeking a vantage point with the lower Troll Wall in clear view. I frantically glassed the lower face, nearly a mile away, finally spotting Carl's big yellow parachute, unfurled and breeze-blown on a shaded terrace near the base.

"Goddamn it, Carl. Get up . . . signal . . ." The canopy billowed gently from the updraft. "Carl!"

Fred arrived and put a hand on my shoulder. Carl hadn't moved. I followed Fred to a grassy field surrounding the grand manor of an expatriate British lord. A pall tumbled from gray clouds as the media streamed in, occasionally stealing glances our way. My center could not hold much longer.

The police chief arrived and I couldn't meet his eyes when I told him I'd spotted Carl on a ledge near the base. The part about no movement ended our conversation. I didn't have the courage to call Jean, but the chief did. Barely. Tears flowed from his eyes though his voice remained calm and stoic. I will never forget his face as he talked with Jean.

"I . . . regret to inform you that your husband has been in an accident, and it doesn't look good." This last detail took enormous bravery to admit. Jean's voice sounded eerily detached over the speaker phone, soberly seeking details as every soul in Andalsnes bore the chaos on her behalf. I stormed outside and pulled on my harness. Nobody knew if Carl was dead, or even seriously injured, and I yelled as much, confronting some with the news. They nodded slowly and shrank away, huddling under trees, waiting.

The whop, whop of the giant military rescue chopper thundered up the valley. It landed in a clearing, arching trees, buckling photographers, scaring all with its powerful thumping. Fred went and I stayed behind, shivering in my t-shirt and glaring up into the rain. Aud came over but I couldn't talk or look at her. I thought about nothing, vaguely hearing the chopper's hammering pitch in the distance. It set down and the crew filed out, staring at the ground. Fred walked over, his face hard as stone. Six photographers clicked shots as we fled back to the lord's house.

As a free citizen, Carl could do as he pleased, but The Castle? I yelled. Carl himself had called the site crazy. The doctor, little more than thirty years old, requested that I go aboard to identify the body. "For what?" I begged. The doctor stared at the floor. The ordeal was far from over, and spared nobody. I felt like the Ugly American who had barged into a quiet little town with a small army and a wad of television money and broke every rule and every heart in the place.

We walked through wet, knee-high grass toward the ship. Amber light glinted off new puddles. How dare beauty show itself when Carl was dead? We moved through the chopper's huge rear hold and back to Carl's body, looking as though he'd laid down to get a load off that leg. No sign of regret on his face. The young doctor and I stood there, mourning a life cut in half, gazing from death as if unhurt. But he'd screamed a music too high to scale, and the cold mountain got him. The distance Carl had tracked away from us brought back the birds and their keening, high on the glacial plateau.

I joined the crowd gathering on the grassy field, everyone gazing confusedly at each other. Someone had to know why and how come. We watched the coroner and two policemen heft Carl's black-bagged body into a white van and roll off into the mist. It felt criminal to leave it at that; but Carl could not die again. That was all. The end.

Fred and I silently drove to Aud's place and I wandered in a traceless land. Even Aud couldn't help me now. Why had Carl jumped from The Castle? I'd never felt such helpless confusion, and could have killed Carl a second time.

That evening I went and found Arnstein who, along with his younger brother, had guided Carl that morning. It had taken them nearly five hours to short-rope (drag by a tethered line) Carl over the glacial plateau and up to the top of The Castle. Carl conducted rock tests and, in seconds, as before, they smashed off outcroppings jutting directly into the flight path. But Carl was determined to go. Arnstein grabbed his camera. As he described to me and others, Carl was dead the moment he launched off the lip, or tried to. On his last exit step, he stumbled and, unable to push off and get some little separation from the wall, he frantically tossed out his pilot chute. With so little airspeed, it lazily fluttered up, slowly pulling his main chute from the pack. One side of the chute's chambers filled with air and flew forward. With one side deflated, the inflated side wrenched the canopy sharply, whipping Carl around and into the cliff.

He continued tumbling, said Arnstein, his lines and the canopy spooling around him like a cocoon. 5,000 feet later, Carl's tightly wound body impacted the lower slab "and bounced thirty feet in the air like a basketball." Arnstein was so sickened by what he'd just shot on his Nikon that he yanked the film from the roll and tossed it into the void, so the images of Carl's last moments were lost forever.

A few days later, Jean hired several local climbers to hike her up to The Castle, where she checked the site firsthand and did what a wife does where her husband has died. Then she traversed the ridge to the original, 1981 launch site, jumped off and touched down for a perfect meadow landing.

I couldn't sit and kept pacing around Aud's tiny apartment. For several weeks, I'd agonized over leaving Norway without her--a puzzling concern for a nomad like me. But life kept shifting. TV work stretched off like a cargo cult runway, inviting a rich future to appear. Then Carl crash-landed and it felt likely I was one and done with production work. Staring at the white stucco walls in Aud's matchbox, I couldn't see any future at all. I don't recall saying goodbye to Aud and Fred, but I must have. I only remember driving through the dark dawn shadow of Troll Wall, heading for the airport in Molde, the giant cliff felt but unseen for all the clouds and rain.

Over the following decades, Carl and Jean's Norway jump became a seminal event in BASE jumping's short history. Several magazines ran feature articles on the couple, but they'd taken a novelist's wand to Carl's accident, and I couldn't read them through. I wasn't surprised when a producer called about a feature-length documentary on Carl, now in production, and asked if I might fly over to Andalsnes and do an interview. Time had worked the sharpest edges off Carl's death, and a trip to Europe sounded excellent. I found myself back in Norway a few months later.

The Trondheim Valley, and that towering junker, Trollveggen, were far more daunting than I remembered--which wasn't much. Andalsnes had modernized but still resembled a sub-burg of Camelot. My feel for the place had gone. Thirty years can blunt the sharpest memories. Mix in drink, work, a failed marriage, and it's a miracle I remember anything. Fred and I reunited and immediately went bouldering at the old haunts--the mushy fields and cow pies, the scabby orange lichen on the rock, gaping up at the monstrous Troll Wall, "doing the joking" as we floundered on short climbs we'd once hiked with ease. The memories stirred. I talked to Aud on the phone and her voice pulled me back. But I still felt lost as the birds on the glacial plateau.

The next day, I met the film crew at a grassy campground directly beneath Trollveggen, rearing a mile beyond us. The director was a jocular young woman from Los Angeles, with heaps of passionate intensity. The director of photography, a pondering Swede, would tuck an entire tin of snuff behind his lower lip and pace, mulling the next shot and spewing vile brown pools like the spoor of a wounded elk. The two went back and forth about the lighting, arguing like they meant it, so I didn't sit for the interview till around noon. It started raining.

They'd paid handsomely to fly me there, so I felt obliged to drop into deep thoughts and important feelings. But I couldn't peel off my armor. The director bore in. As I recounted the details, and Carl's eccentric stoke and fearlessness, the top layer didn't so much wear thin as sludge from far below came bubbling up. Yet I spoke without color, owing to the gray way the past came back to me. The questions moved to The Castle, and the rescue chopper. Standing in a drizzle and glaring up, I slammed through the looking glass.

For several minutes I said nothing, sinking lower in my chair. The rain beat down and we stopped filming. I didn't move. The director pulled a blanket over my shoulders. For an instant, I could see my life with jarring clarity as it ran from that July day in Andalsnes, three decades before, and how my native love for cinematic narratives never made it off that rescue chopper. The part of me that can actually write was wedged like an iron strut between then and now as I continued to muddle along in productions I didn't believe in, without passion or inspiration, an also-ran in an industry made for me--a selfish take on "The Jump," as they called it, but Carl's death was the ogre who prowled my unconscious, setting me on my screwy course in life.

Over the next half hour, I'm uncertain what I said, but I meant every word--and it was mostly news to me. Then the director asked why I thought Carl had risked a jump that he'd previously called "crazy." For years, this question had lingered over The Jump, adding texture and intrigue to the strangeness of Carl's last words.

As Arnstein had later told Stein Erik Gabrielsen, as Carl stepped toward the edge of The Castle, he abruptly paused and asked, "Do you boys know the Bible?" Wide-eyed and anxious, they said, "Yes, of course." "Remember when the Devil takes Jesus high up onto the temple roof," asked Carl, "and tempts him to cast himself off, for surely the angels will rescue him?" "Yes," Arnstein had said. He knew the story. Carl reached one hand over the other shoulder, patted his parachute, and said, "I don't need angels."

The man who would walk on water and fly through the air--is he closer to God, or possessed, gaslighted by glory, adrenaline, and a lifetime of narrow escapes? Carl turned, took two steps toward the edge and, on the third step, he stumbled.

That night I sat alone in my room, muddling through an old issue of Granta I'd nicked from the hotel lobby. For years, I'd stepped on the gas and whoosh--the far side of life was fast approaching. Scrolling back, I could finally sense the penumbra of Aud and I, like perfume on an old pillow. We'd spoken several times and thought it best not to meet in person. When I called and asked her to reconsider, she arrived in the lobby ten minutes later. We stared at each other, dazed to realize that once we'd been young together. I could have ridden that feeling into the ground. Instead, I powered up my laptop and showed Aud photos of my two daughters: Marjohny, with all the freckles, and Marianne, a recently minted MD, both stunners because they take after their mother. When Aud's daughter arrived, I was staring at Aud herself--a young woman exuding life the way a lamp gives off light. She looked at me curiously. A man from her mother's past, standing before her and looking at the future. It's all an enchantment.

Stein Gabrielsen and his friend, Eric, had barely arrived in the Romsdalen valley when a local drunkard pointed to Trollveggen and said, "That is the Devil's mountain." Eight hours later, Carl died quoting the Devil tempting Jesus to fly. Eric, a wizard in the air, jumped the Troll Wall three times over the days following Carl's death. On his last jump, Eric logged a thirty-second free-fall with a two-second canopy ride before landing in the rocks, miraculously unhurt. He declined to document the record free-fall because the only way for someone to top it was to bounce. "Get me out of here before I die," he told Stein. Stein quit drinking on the spot and hasn't jumped since.

Eric is currently a healer in Berlin and skydives regularly. Stein runs a small church (Saint Galileo) and teaches kite-surfing in Miami. He still gets occasional flashes of Eric nearly going in during his thirty-second free fall. "For now," he later wrote, "I am content with the knowledge that I am a fool. Every day I thank my angels and pray for wisdom."

In winter, 1989, Arnstein Myskja, the teenage guide who witnessed Carl's last jump, was swept to his death by an avalanche while climbing the Mjelva Gully, rising above the Mjelva Boulder, the moss-covered stone where Fred and I practiced climbing, waiting for the clouds to part on Trollveggen.

Aud is a nurse's supervisor, has two teenaged daughters, and is married to a fellow Norwegian who manages oil platforms in the North Sea.

Fred Husoy went on to climb many new routes in the Trondheim Valley, the Alps, and the Himalayas. He led the local rescue team for many years and, through innovative, often perilous efforts, saved dozens of climbers injured on the Troll Wall. He is married to a doctor and has two sons.

Half a dozen years after The Jump, while parachuting onto a limestone Tepui in the Venezuelan rainforest, Jean Boenish open-fractured her leg, greatly curtailing her BASE jumping career. A common saying in adventure circles is that BASE jumping has killed more people than malaria.

The film about Carl Boenish, called Sunshine Superman, earned critical acclaim. Producers felt robbed that it didn't earn the Academy Award for live-action documentary. The director invited me to a private screening shortly after the premiere, thick with industry people, but I left early. It took me three times to finally watch it through.

A few months after returning from Norway, I came tumbling down in a climbing gym, of all places. The first thing I saw when I rolled onto my ass was my tibia jutting from a fist- sized hole in my shin. I spent the next forty-five days in the hospital. One time in the wee hours when I couldn't sleep and the morphine carried me off to the ethers, I gazed down and saw a girl and a boy dancing to The Who in a bar on a thousand-year-old street.

Related: The Third Man: How a Dead Alpinist Saved Me From the Grave

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.