This reporter had plenty of memories of Terry Francona's time with the Boston Red Sox

Baseball is the leading game in the numbers-don’t-lie-category, mainly because there are so many of them.

That’s for players, at least. It can be different for managers.

Casey Stengel, whose first job as a manager was in Worcester, is in the Hall of Fame. Stengel managed, in order, the Brooklyn Dodgers, Boston Braves, New York Yankees and New York Mets.

He was 1,149-696 with the Yankees, 756-1146 with the other teams. He won seven World Series in 12 years with the Yanks, none in 13 years with the others. This fact prompted Hall of Fame pitcher Warren Spahn, who played for Stengel with the Braves and the Mets, to say:

“I knew Casey Stengel before, and after, he was a genius.”

Terry Francona’s managerial career was a bit like Stengel’s except there has been no “after” yet. He has just retired as manager of the Guardians. Francona is 64, managing since he was 38, but younger than five other active big league managers. Francona has 23 major league seasons to his credit, only eight in Boston.

But those are the years for which he is remembered most.

Is he a Hall of Fame manager like Stengel? A committee will decide that with a few seasons of perspective in the rearview mirror. Hall of Fame or not, Francona was a really, really good manager who might never had outlived his four years of failure in Philadelphia if Theo Epstein had not had the good sense to hire him in Boston.

When Francona was hired to replace Grady Little for the 2004 season, it raised some questions about Epstein and if he were in a little over his boots, perhaps. Francona was three seasons removed from the nightmare in Philly, where his teams played in rat-infested Veterans Stadium from 1997 through 2000 and finished below .500 every season.

Philadelphia fans have been known to boo successful athletes and managers. Francona was a human dartboard there. In Boston, he told stories about driving home to suburban Yardley — a town within sight of where Washington crossed the Delaware — and having people scream and salute him, so to speak, with the universal seal of disapproval.

As so often happened during Epstein’s time in Boston, he was right. Francona, with time to reflect on his Philly years, was the perfect choice to replace Little. Francona was analytical, but not introspective. He had been around baseball his entire life, and his instincts were excellent. Francona’s dad, Tito, was from the old school, but Terry Francona was not.

One of the first things he said as Red Sox manager was, “I’ll never tell one of my players that, back when I was a player, we did it this way.”

Francona’s strength was his ability to keep it together when things went badly, as they always eventually do in baseball. No team before, or after, 2004 had come back to win a playoff series from a 3-0 deficit. In 2006, the Red Sox seemed to be turning back the clock the wrong way. They were in first place in July and missed the playoffs entirely.

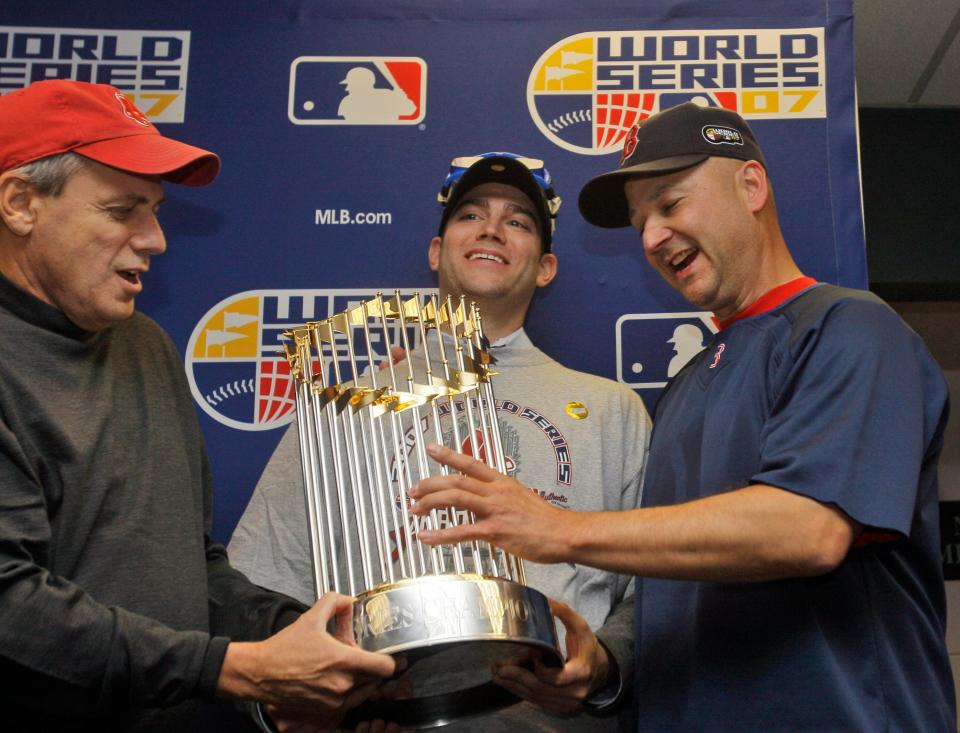

Francona then led them to a World Series triumph in 2007.

Everything fell apart in 2011, and he departed. It had been eight years, and for Red Sox managers, seasons are measured like dog years. Through no fault of his own, it was indeed time to go. Francona’s subseqent 11 years in Cleveland added to what he had done in Boston and restored his reputation.

Thus, the Hall of Fame talk.

When Francona arrived in 2004, reporters had easier and more informal access to the manager. Francona was quite different in person than in the lights-camera-action press conferences, so he left a legacy of stories.

Here are some favorite Francona moments from this perspective:

∎ All managers hate to be called “coach,” but Francona hated it more than anyone. There was a radio reporter in Chicago who extended Francona’s limits — he got his first name wrong, too. He would call him coach Tony Francona.

In one pregame session, the radio guy started a question with, “Coach…” and Francona stopped him dead by saying he was the manager, not a coach. The radio guy responded with, “Sorry, Tony.”

∎ Francona was proud of his work, but not an egoist. He was never named Manager of the Year for all he won in Boston, and was not upset with what some might deem a snub. “I shouldn’t be Manager of the Year,” he once said. “The Manager of the Year should be the guy managing the Pirates, trying to make winners out of that team.”

∎ Personally, I never called him Tito. I was old enough to remember his dad as an excellent player who got MVP votes for the Indians in 1959 and was an All-Star with Cleveland in ’61. That man was Tito. The Red Sox manager was Terry.

Doing some odd research one time, I came across an item from a Sox-Cleveland game at Fenway during which Tito Francona was on first base with the bases loaded and Earl Wilson on the mound for Boston. When Wilson went to throw a pitch, Francona yelled, “Hold it, Earl,” which caused a balk. The now-Guardians went on to score nine more runs in the inning.

I told Terry about the story, and he had not heard it, suggested that his dad loved talking about his playing days, would be glad to hear from me, and gave me his dad's home phone number. So I called and asked Tito about the play.

“Don’t remember that,” he responded quietly. When I told the son about the end result of my call, he said, “Smart man.”

∎ In May 2007, the Sox were on a road trip that included stops in New York and Texas. On Sunday in New York, I asked Francona an injury question pregame, and he told me to get to him about it after the game. At the old Yankee Stadium, reporters had to get to the clubhouses in shifts on the elevators, and I was a second-shift guy this day.

So I asked the injury question, and Francona said curtly that he had already answered it. I raised my arms in disgust, which caused him to bolt from the interview room, calling me a nasty name — you can guess — on his way out.

Two days later, in Texas, he had PR head Pam Kenn ask me to meet him in his office, which I did, and he was apologetic and remorseful and even turned a couple of players away as he sat and talked with me cordially for more than an hour.

∎ Francona was a baseball genius, but the outside world could be a mystery. He admitted to being one of the world’s slowest drivers — one of those “get a horse” people in the breakdown lane, and needed a lot of help from Kenn, and Phyllis Merhige of the commissioner’s office, to navigate off-field business.

He had a hard time holding grudges. The Globe’s Dan Shaughnessy was hard on him, as he was with just about every Sox manager, but the two wound up writing a book together. Subsequently, he and Shaughnessy were invited to our annual Baseball Writers Dinner in January and made a date to meet for lunch or something.

Francona got to Shaughnessy’s room at the appointed time and pounded on the door until, finally, some sleepy-eyed guest opened it. But it was not Shaughnessy. Francona had the right room number but the wrong hotel.

∎ One time, I wrote a scathing column about how the Sox had mishandled Josh Beckett. The next day, I got a message to check in with Francona and Epstein in the manager’s office at Fenway before the game. They reamed me out royally, then Epstein stormed out of the room. After Epstein departed, Francona pulled me aside and said, simply, “Bill, next time, just check with me first.”

∎ So many little things happen in a baseball game that it can be hard to keep track of them. The managers who can are the great ones, and that was Francona. One time, after 2004, he was thinking back on Dave Roberts’ steal of second base in Game 4 of that ALCS and how much went into that epic play.

Roberts was on first pinch-running for Kevin Millar. The stolen base attempt seemed obvious, but it was not that simple. Bill Mueller was up, batting left. If Roberts steals, that takes away the hole on the right side, and Mueller had shown he could pull Mariano Rivera.

The Sox had studied tape and compiled the numbers on Roberts’ speed and Jorge Posada’s arm and concluded that unless Roberts fell down along the way, he would steal the base.

Which he did, but only by a fraction. When the Sox reviewed the play the next day, they discovered that Posada’s throw to second on that play was the fastest one he had ever made against the Red Sox.

Francona is not the only Red Sox manager to win two World Series. Holy Cross alum Bill Carrigan did that in 1915 and 1916. Francona is, however, the only Red Sox manager born in South Dakota. That fact does not necessarily add to his Hall of Fame credentials, but it is a great footnote.

So is Terry Francona going to join the likes of Casey Stengel in the Hall of Fame in years to come? I don’t have a vote in that matter, but if I did, I would cast it for him.

—Contact Bill Ballou at sports@telegram.com. Follow him on Twitter @BillBallouTG.

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: One reporter's memories of covering Francona with Boston Red Sox