Picture Nick Saban the point guard and Nate Oats the wide receiver ― it actually happened

The same person often popped into John Fazio’s mind when he taught management for 13 years.

Fazio instructed college students in Athens, West Virginia and Marietta, Ohio about Level 5 leaders, the fifth stage of a leadership pyramid. Level 5s possess two qualities: An intense desire for the success of an organization and good humility. Overall, they’re uncommon to find, but Fazio encountered one during his adolescence. He met a Level 5 in junior high in Monongah, West Virginia.

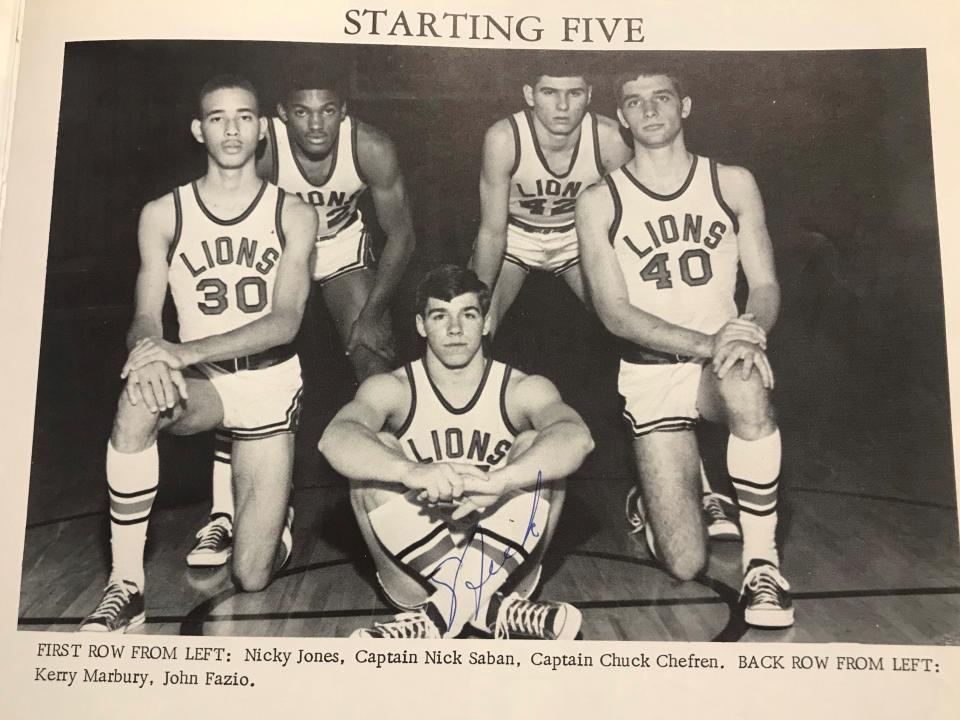

“When I taught that class," Fazio said, "I always thought about Nick."

Nick, as in Nick Saban; He and Fazio went to high school together. Fazio brought him up all the time to students. At one point in a class, they discussed Saban’s process and the way he coaches, ultimately relating the conversation to leadership.

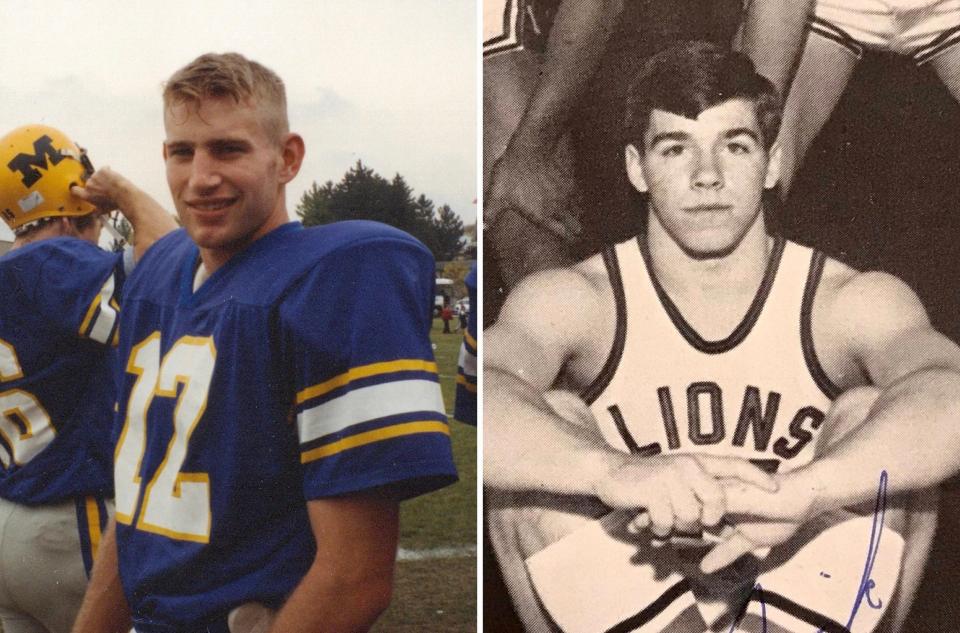

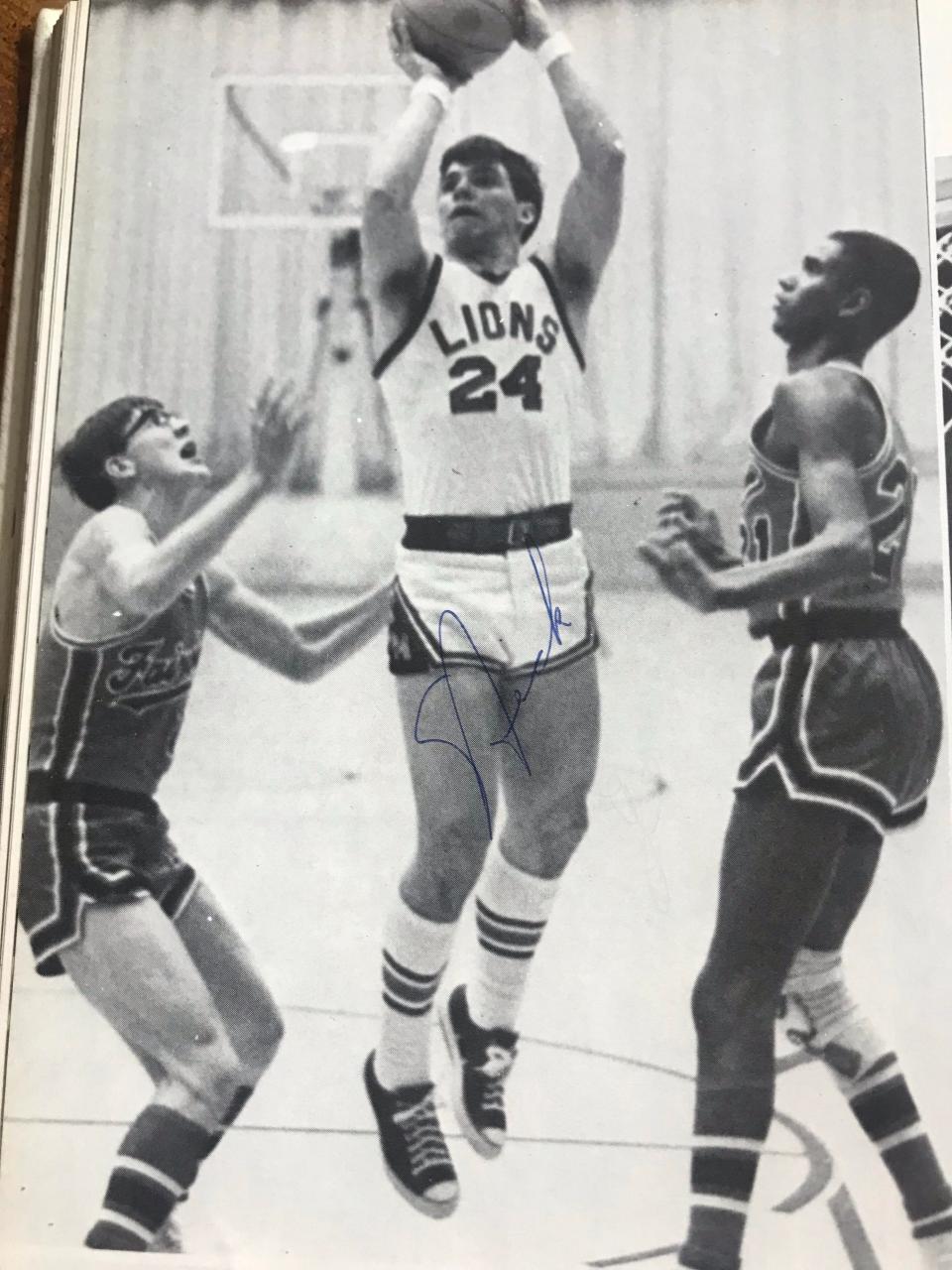

Fazio saw Saban’s leadership firsthand more than a half century ago when the two played sports together. Football was of course part of that, but Fazio and Saban also started on the basketball team. Saban was a captain for the 1968-69 team and a three-year starting point guard.

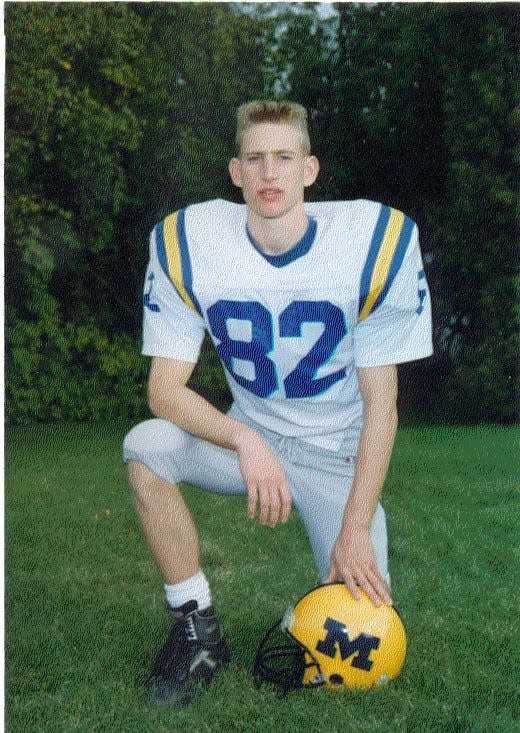

Saban's basketball teammates knew him for his competitiveness and attention to detail, among other attributes. Apparently those are two good indicators of a future Division I coach; Football teammates said similar things about wide receiver Nate Oats.

Yes, there once was a time when Alabama football’s coach played basketball and Alabama basketball’s coach played football. Saban stayed with hoops through high school, while Oats played football into college.

Saban then joined the Kent State football team, and Oats focused primarily on basketball at Maranatha Baptist Bible College. The long-term prospects of their playing careers in each was limited, so they weren’t about to go pro in their secondary sports either. Still, Saban thrived at times on the hardwood, and Oats made plays on the gridiron.

There’s a reason Oats preaches toughness to his basketball players. That’s how he played football. It’s also no accident that Saban has used the analogy of managing the offense like a point guard with quarterback Jalen Milroe throughout the 2023 season.

Saban knows exactly what that takes.

NICK SABAN VOTING: How many votes has Alabama football coach Nick Saban gotten in elections over the years? We counted

WILL REICHARD: 15 untold Will Reichard stories: Duck disputes, dog negotiations and his flu prom

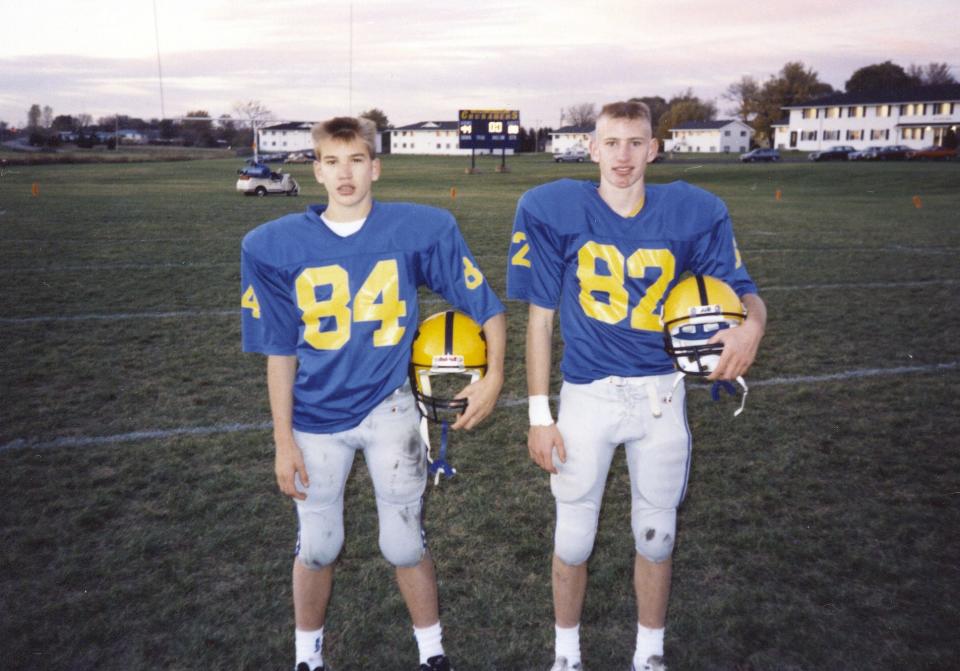

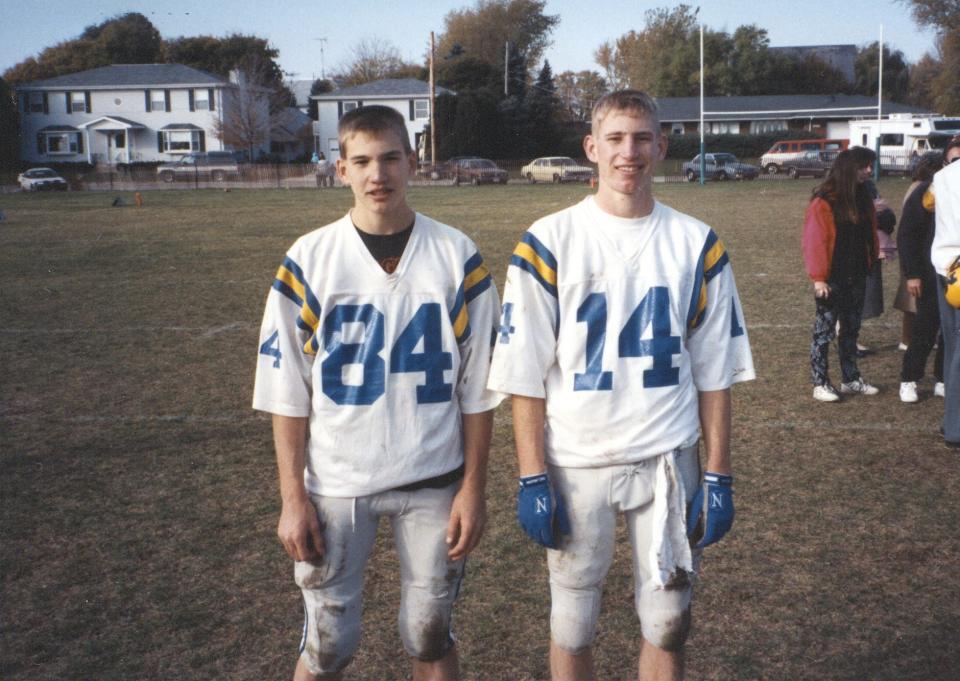

Nate Oats, the wide receiver and backup quarterback

Oats saw former Alabama basketball guard Kira Lewis Jr. distraught in the locker room. Lewis had just missed two free throws in the final seconds of the 2019-20 season opener against Penn. Then, the Crimson Tide lost the game 81-80. To make matters worse, it was a buy game and Oats’ Alabama debut.

With Lewis crushed, Oats’ mind went back to almost 30 years prior. He didn't think of a basketball moment, though.

During the 1991 season, Oats’ junior year of high school, Maranatha Baptist Academy’s starting quarterback Luke Akins sprained his knee. The Crusaders needed a fill-in short term. Oats wasn’t a quarterback, but he knew what the quarterback was supposed to do. That was enough for the coaches at the small Christian school to make him the signal caller.

“I didn’t have a great arm, but I could run the offense,” Oats said. “I wasn’t going to screw up and hand the ball to the wrong guy. I was going to get the ball where it was supposed to go.”

He accomplished that for the most part, but there was one time he didn’t.

In a close game, Maranatha had a chance to score in the red zone. But instead of walking away with points, Oats threw an interception. The Crusaders eventually lost by a touchdown.

That became the only loss of an otherwise undefeated season. When Oats got home, he chucked stuff around his room in the basement. His dad had to console him.

“I was so ticked off after that game,” Oats said. “I felt like I let the team down.”

He made more plays for the team as a receiver. Oats recalled having six games over 100 yards receiving and one 200-yard game his senior year when Maranatha went undefeated.

“He wasn’t the most athletic, but he had really good hands,” Akins said. “He worked and worked and worked at his routes. He ran really good routes and could shake up the (defensive) backs and get himself open.”

Akins described Oats as methodical in his thinking, from his hip movement to where his feet cut in routes. Said Akins: “He was just driven to be detailed and worked his rear end off.” The two labored together many hours after practices, with Akins throwing and Oats catching passes. That translated to success in games, particularly with the 60s series.

They stole it from the college; The academy was a prep school on the same campus as the college, formerly called Maranatha Baptist Bible College. That’s where Oats eventually got his degree and played football for two seasons.

The set of plays in the 60s series went something like this: The team gets in the huddle and calls “60 series.” Once the huddle breaks, three receivers split out. Then each puts a number behind his back for the quarterback to see and know what route his receiver would run.

No number? A 60: A quick turn and throw at the line.

61? A quick slant across the middle.

62? An out route.

63? Sell the slant then bust it up the field to the outside. That was a favorite for Oats. At 6-foot-2, Oats would see smaller defensive backs and knew he had them. He would cook them on the 63 fade. There were a few of those in Oats’ 200-yard receiving game.

“A handful of times, we would be in the huddle, and he would say, ‘Just throw me the ball,’” Akins said. “He would get open and he scored on (63 fade) regularly.”

There was one memorable pass on which Oats didn’t score, though. Neither he nor Akins have forgotten the moment, even 30 years later.

Unafraid Nick Saban, the point guard

Fazio stood underneath the basket, ready to grab the rebound one day in the late 1960s.

He was in a prime spot to secure the ball during this intrasquad scrimmage one day with the Monongah boys basketball team. Then he wasn’t.

Saban made sure of it, preventing Fazio from getting the board. It didn’t matter if Saban was a smaller guard.

“He was not afraid to go inside under the basket to get rebounds against bigger guys,” Fazio said.

Some Monongah teammates scrimmaged passively. Not Saban. Even a half century later, Fazio still remembers the consistency with which Saban did everything. Intensity is the word that came to Fazio’s mind.

Running steps? Saban didn’t lag. Sprinting around the court? He went hard.

“Nick played at full speed all the time,” Fazio said.

Deion Sanders, Drago and Nate Oats ditching gloves

His freshman year, Oats got some time with the varsity team. Gloves had started becoming a big thing for receivers, and Oats had to have them. His coach, the late Rich Akins, always gave Oats a hard time about the gloves. The coach had an old-school mentality; Want to catch better? Just rub dirt on your hands. Meanwhile, Oats liked some flash. He wanted gloves.

“You've got to look good to play good,” Oats said. “Everybody wore gloves.”

Oats did until one game freshman year. He ran a route and found his way to the end zone. The quarterback saw Oats and threw him the ball for what should have been an easy touchdown. The ball went right through Oats’ hands, though.

“Get the gloves off, Oats,” his coach yelled loud enough for everyone at the game to hear.

“Nate had those gloves off before the ball hit the ground,” Luke Akins said.

The gloves didn’t stay away forever, though. Oats went and got the Neumann gloves, what Oats called the “real gloves,” before his sophomore season. They might have had some function, but fashion also mattered to Oats. He wanted to look the part.

Oats watched Deion Sanders with the Dallas Cowboys, Oats’ favorite team originally, and he saw how Sanders carried himself.

“I was a big fan,” Oats said. “Prime had a little swag. He’s still got a little swag.”

Sanders had a towel, so Oats did too. “I had to make sure I looked good,” Oats said.

That also applied to his hair in high school. Oats sported a flat top. He said it was inspired in part by Ivan Drago from Rocky IV. Oats’ nickname at one point was Vanilla, as in Vanilla Ice.

Nick Saban obliterating the press

Saban had just finished coaching a football game, and a marquee one at that one night this past October. Alabama football beat Tennessee 34-20 at Bryant-Denny Stadium in a ranked game between rivals. Then Saban, standing behind the lectern, fielded a question about Milroe running more in the second half, when Alabama scored 27 unanswered points.

Saban praised Milroe for how he played, particularly after halftime and how he adjusted. Before long, in his answer, Saban talked hoops.

“You’ve got to get a feel for how the guy is playing you,” Saban said. “It’s a little bit like if you are playing point guard and the guy’s slumping off, you shoot a three. If he’s guarding you close, you drive around him. But when you’re reading a defensive end on some of this stuff, I think you’ve got to get a feel for it.”

Saban thrived in the same way as a ball-handler in his basketball playing days. Saban could read opponents at a high level. Just ask his fellow captain on the Monongah team, Chuck Chefren.

“He always worked on the other teams’ deficits,” Chefren said. “If he was a little faster than the other guy or the other guy maybe was left-handed, couldn’t go a certain way, things like that.”

That ability made Saban ideal for finding ways to break the press. Monongah had set plays to get around it, but Saban became the optimal player to captain the press-busting ship.

Monongah needed that. Fazio recalled opposing teams pressing them a lot because not enough could handle the ball well. Saban helped thwart those attempts best he could.

“I was impressed how he moved with the ball up and down the court,” Fazio said.

Once Monongah could get up on the press and within 15 feet of the basket, all of the players could shoot well enough. There wasn’t a three-point line back then.

Saban was a good scorer but not a prolific scorer, Fazio recalled. Here’s the rest of Fazio’s scouting report: Saban was unselfish with the ball and liked to shoot from the top of the key. Saban also had a decent jump shot.

Monongah didn’t have a big enough court on which to practice, so Saban’s team went to the National Guard armory. It was a shared court with other high school teams. Each day, the 15 or so Monongah players piled into two to three cars to drive to practice.

The Fairmont team got priority because the court was in Fairmont, so Monongah had to practice later. That meant not getting home until 8 p.m. or so.

“You’d have the temptation to skip practice because it was such a long day,” Fazio said.

Not Saban, though. At least not that Fazio can recall. In fact, Fazio couldn’t remember a time he ever saw Saban miss anything.

“He was always reliable,” Fazio said.

And competitive. So Saban probably didn’t love the fact the basketball team didn’t have as much success as football. Monongah was much more of a football school. Many of the football players just happened to also play basketball.

Injuries that stemmed from football often got in the way of basketball winning games. That certainly didn’t stop Saban from trying, though.

“Probably more competitive,” Fazio said, “and more determined than any athlete I knew.”

That sounds about right for the seven-time national championship-winning coach.

Blue collar football, feat. Nate Oats

Don’t confuse Oats’ love of flash for a lack of grit. Despite being a receiver, Oats was known for his blocking, said Oz Price, Oats’ high school and college teammate.

“He was tenacious when he would block,” Price said. “He would get after it.”

Oats wanted to compete any way he could, for as long as he could. Case in point: He played two years of football at the Division III level in college. Oats competed his sophomore year then stopped and focused solely on playing basketball. Then, once he had used up his four years of basketball eligibility, Oats sought an outlet to keep competing in college athletics; he decided to come back and participate in football his fifth year.

“I do think (football) helped mold my coaching career,” Oats said. “There was just the toughness. There’s something to be said, even if I didn’t play at a high level. I think football has a degree of toughness. I never want my teams to be soft.”

That's a mentality some would call blue collar.

Nick Kelly covers Alabama football and men's basketball for The Tuscaloosa News, part of the USA TODAY Network. Reach him at nkelly@gannett.com or follow him @_NickKelly on X, the social media app formerly known as Twitter.

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: In past life, Alabama's Nick Saban (PG), Nate Oats (WR) reversed roles