Ordeal By Alps With Allen Steck, Father of American Climbing

This article originally appeared on Climbing

Editor’s Note: Allen Steck, a legendary Yosemite pioneer, passed away at his home in Bishop February 23 at the age of 97. Steck led an illustrious career, establishing first ascents around the world. He began climbing in Yosemite in 1947 and went on to participate in the first major American mountaineering expedition to the Himalaya, on Makalu in 1954. He made the first ascent of Mount Logan's Hummingbird Ridge, which is today unrepeated and considered one of the most challenging climbs in mountaineering history. Along with Steve Roper, he was the longtime editor of Ascent.

We have an obituary in the works, but in the meantime, here’s an article by Steck which first appeared in Ascent 2012.

A middle-aged man hung from the nylon webbing that connected his wrists to the ceiling beams of his living room. His arms gyrated and his feet barely skimmed the floor. Greek music blared as I entered the house, early for a dinner party. A folded wheelchair tilted against a far wall. Only a week earlier had doctors given permission for my close friend and climbing partner Allen Steck to tread gently on his two shattered ankles. This night was to celebrate his partial recovery. He hadn't danced for months, but the time had come. It was February 1990.

Rachet back to 1949. Steck was a neophyte climber using hemp lines and steel carabiners. Imagine that not too many years later this man became one of the most accomplished mountaineers in American history, visiting dozens of countries, climbing with the stars of several generations, and learning the modern protection gadgets as well as anyone.

Today, come visit the Berkeley climbing gym. Yes, he's still around. At age 85 he delicately works his way up 5.10s, arthritic joints creaking, impressed by the diabolical cleverness of the course setters.

Allen Steck's name is often associated with Mount Logan's Hummingbird Ridge. This epic of 1965 was his defining moment, and no one has yet repeated this preposterous route, though some have died trying. But long before, Steck had made his mark.

As a teenager in the early 1940s, Steck went often to California's High Sierra with his dad. Languid days included fishing, exploring, and even a new route on Mount Maclure, Yosemite's second-highest peak, with his brother, George. Soon came a rather extreme adventure, serving on a bobbing destroyer escort in the far-western Pacific. Below decks, fiddling with turbo-electric motors, Steck wondered if an unseen torpedo or a kamikaze would end his life. But this was early 1945 and the Japanese were scarce. Soon he was a civilian again.

Twenty years old and what to do? Take advantage of the Servicemen's Re-adjustment Act, of course. Better known as the GI Bill, this grant meant money for education, subsidized housing, and incentives to travel abroad to study. Steck spent a few years at UC Berkeley, but wanderlust soon led him to the Old World in the spring of 1949. He was already a fledgling Yosemite climber, but this enterprise, described in the following piece, opened up a new world.

No other climber of Steck's generation traveled to so many remote areas: to first ascents in the then-barely explored southern Sierra, and wild climbs in the interior of British Columbia. Gripping stories emerged constantly. In Peru's Cordillera Blanca, in 1952, he accompanied back to civilization the body of a friend who had died of cerebral edema. On New Year's Day, 1955, he was dug out of an avalanche near Lake Tahoe with his face as blue as the winter sky. By happenstance, friends coming along minutes later had seen the avalanche track and a few trapped survivors gesturing to where Steck was buried. Another avalanche, in the Pamirs, nearly claimed him.

High on a snowfield on Aconcagua in 1973 he came across the thawing body of a deceased American woman. During the horrifying 1974 tragedy in the Soviet Pamirs, where eight Soviet women froze to death at 23,000 feet on Peak Lenin, Steck was first upon this sad scene and recalls the startling blue eyes of one corpse. In 1976, in the Karakoram, during the first ascent of "the world's most beautiful mountain," Payu, he let his Pakistani cohorts have the sole honor of the summit, stopping a few hundred feet short. A tiny fall in deepest Algeria in late 1989 resulted in the above-mentioned shattered ankles and an epic three-day journey back to the States for repair.

Steck's decades of climbs include nine first ascents in Yosemite Valley, the most noteworthy of these being the somber north face of Sentinel Rock. This five-day effort, with the legendary blacksmith John Salathe, tests climbers even to this day. Although Steck wondered if it would ever be climbed again, he himself did it four more times, the last at 74.

Other notable achievements: a new route on Mount Waddington; a daring attempt on then unclimbed Makalu; the third ascent of the Salathe Wall. Steck was the first American to climb one of the six great north faces of the Alps. Closer to home, in 1963, was the first one-day ascent of the Grand Traverse in the Tetons. Of this venture he later wrote: "I saw the inevitability of a struggle, and a good struggle now and then is a tonic, for while it taxes the leg and arm muscles, it tends to relax those in the cranial cavity." In 1982 Steck and his brother, after establishing food caches, traversed the entire length of the Grand Canyon, following the river below the north rim for 80 days without coming out to civilization.

Mountaineering was hardly Steck's obsession. He was a family man, with a wife and two splendid kids, a businessman who co-founded Mountain Travel, one of the first adventure-travel companies, and a writer. "High Angles in the Eastern Alps," his first real published piece, appearing in the June 1950 Sierra Club Bulletin, described the wanderings Steck made with Karl Lugmayer in 1949. A year later came "Ordeal by Piton," his stirring account of the Sentinel climb, which ended with these words: "The reason, the incentive, the motive for all this? It is an intangible, provocative concept that I shall leave to the reader to explain. Some think they know why; others despair of ever knowing. I'm not too sure myself."

One of Steck's finest articles appeared in the first issue of Ascent, the Sierra Club's mountaineering journal, debuting in 1967, of which we were co-editors. The piece was a thoughtful and gripping account of climbing the Hummingbird Ridge. Steck was the inspiration behind Ascent, and together with a small cadre of fellow climbers, we kept the magazine (later in book form) going until 1999.

Steck also co-wrote (with Lito Tejada-Flores) a fine manual called Wilderness Skiing. He and I co-wrote Fifty Classic Climbs of North America, a project that demanded much typewriter time and tens of thousands of vertical feet, the vast majority of which was highly pleasant "research."

My memories of Allen date back to the early 1960s, when he hired me to work winters at the Ski Hut, an old Berkeley institution where he was the manager. Before work, along with like-minded comrades, we would endure four-mile runs in the hills or frigid sessions at the local rocks. Later he and I climbed in Mexico, Turkey, Italy, England and many of the Western states. It was great fun, and Steck was safe, fast, a superb routefinder and strong. We climbed the North Face of the Grand Teton almost entirely unroped, leaving the valley floor at dawn and returning before sunset. This was 1977, and Allen was 51. I was 36.

But perhaps best of all the memories I treasure about Allen were the hundreds of lunches and dinners at his house, eating at a crafted table in his exquisite, self-designed kitchen-cum-dining room. Many of these occasions were supposedly "professional" meetings, as we worked on various projects. The business talk never lasted long, for soon it was time for more wine and outlandish climbing stories. Many famed climbers visited the house--I can think of Lionel Terray, Walter Bonatti, Barry Bishop and Galen Rowell, among others. I wish I'd been there the night that conversation turned to personal altitude records. Forgetful Allen, lulled by wine and perhaps thinking his own top elevation might trump every other guest, asked Willi Unsoeld his high point. The table went silent.

"Well," drawled Willi, "I guess Everest."

And the food! Dungeness crab appeared routinely throughout the winter. Other menus featured open-faced roast-beef sandwiches with caramelized onions or perhaps deep-fried calamari rings with homemade mayonnaise. I give the place three stars. Long may I go there. --Steve Roper

I stepped off the Arlberg Express in the Vienna train station in early May, 1949, and met Karl Lugmayer. How was I to know that our adventures that summer would be so profound? We had only corresponded--he had written to the Sierra Club in San Francisco asking about climbing possibilities in California. In reply the Club mentioned that two members of the local Rock Climbing Section, Fletcher Hoyt and myself, were in Zurich, and that Karl should contact us. Fletcher and I had climbed together in Yosemite and had gone to Zurich to study German and Russian, which, as veterans, we were able to do under the G.I. Bill. It was our intention to climb some of the great routes in the Dolomites that summer. We were obviously excited to receive Karl's letter introducing himself and suggesting that he would be interested in climbing with us in the Eastern Alps.

Tre Cime di Lavaredo, three huge freestanding limestone towers and emblem of the Italian Dolomites: Cima Piccola, Cima Grande and Cima Ovest. Steck climbed here after WWII, introducing nylon ropes to the world of recreational climbing--until then hemp or natural-fiber ropes had been the norm.(Photo: istockPhoto)

We stood at the station and looked each other over. Karl, a member of the Osterreichischer Alpenklub, was a student of physics at the Technische Hochschule in Vienna. Climbing for him had been a passion for several years. He was a handsome fellow with an easy manner and a classic climber's look, broad shoulders on a thin, wiry frame. We liked each other instantly and soon began to form a plan for the summer. He had an extensive knowledge of the classic routes in Austria and Italy. Some of these routes I was aware of, but the immense 3,600-foot northwest face of the Civetta, which would be one of our adventures in northern Italy, was unknown terrain for me. From my reading in Zurich I knew a bit about the history of European climbing, which surprised Karl, and of course I knew about the first ascent of the north face of the Eiger, in 1938. I was therefore pleased when we visited a climbing shop in Vienna owned by Fritz Kasparek, part of the team that had made the ascent 11 years previously. Kasparek was an amiable fellow, we talked about climbing, and he gave me a hammer that he had made.

Unfortunately, an accident during an Easter ski excursion would prevent Fletcher from joining in the upcoming tour. We managed an ascent of the Todispitze, but were hit by an enormous storm and struggled through heavy snow to get back to a cart track that led downward. The slope above us was very steep and as we were skiing across a gully, a small avalanche came down upon us, quickly and quietly. My ski tips stuck under some ice blocks in the track and the snowy torrent swept over my back, but with enough power to drag Fletcher about 60 feet down the slope. He was unhurt until a second slide occurred, shattering his kneecap. Luckily he had a small squeeze tube of morphine, which lessened the pain during the eight-hour descent, over a distance that would normally take 45 minutes, to the village for help. He underwent surgery in a Zurich hospital, but his climbing days were over for several years owing to further surgery.

Karl's studies would end on July 9 so he suggested that I stay at his parents' home in Wolfern, near Steyr, in Upper Austria, during the period he was at the university. My German improved enormously during these weeks. Karl's father was a teacher and my lodging actually was in the local school, so it was pretty noisy during the day. Karl's parents were most gracious and hospitable to take care of me until Karl was free for our summer's tour. His mother told me with great enthusiasm about how their village was liberated by American forces in 1945. The U.S. troops, all carrying rifles, shouted, "Raus, raus," ordering all the townspeople out of their homes, with hands high, to be searched. It was not exactly pleasant, but certainly better than being under the Russians, whose line of control was a few miles to the east.

Lugmayer and steeds at rest in Sillian, Austria, just before entering Italy. Steck’s bicycle had defective brakes and he crashed with some regularity during his tour of the Alps by pedal power. (Photo: Allen Steck)

Karl had a free week in late May so we met in Wolfern and left for the Kaisergebirge, he by bicycle and I by train and bus. Our first stop was the Gaudeamushutte, the famous approach to the Kaiser from the south. A few training climbs gave us a chance to become a moderately skilled climbing team, though I had trouble convincing Karl to use the hip belay instead of his shoulder belay. We had two 120-foot nylon ropes, the type that were used by the U.S. mountain troops in the Italian campaign: I had brought one and the Sierra Club had sent him one earlier in exchange for some German climbing books. To my knowledge, this was the first time synthetic ropes were used for recreational climbing in Europe, certainly in the eastern Alps.

Eventually we hiked up to a pass and scrambled down a rocky gully to the Stripsenjochhaus, which was close to our first major objectives: the famous routes on the Fleischbank. Not many people were in the mountains in those days and, as we were the only guests of the hut, the hut keeper Peter Aschenbrenner welcomed us warmly. Peter was a surviving member of that tragic German expedition to Nanga Parbat in 1934 where nine climbers and Sherpas perished during a lengthy, fierce blizzard. A lively discussion followed about the benefits of nylon ropes, the first he'd ever seen.

The rock of the Kaiser, particularly on the Fleischbank, is good, well-featured, solid limestone with a blue-gray hue unlike much of the rock of the Italian Dolomites. After a few training climbs, we turned our attention to the southeast face of the Fleischbank. This now-classic climb, rated a grade VI, was first climbed by Fritz Wiessner and a companion in 1925. Once you complete a pendulum low on the face, an acrobatic move, you cannot descend from the climb. Only eight months earlier than our visit, a team of four, friends of Karl, were overtaken by a massive thunderstorm on the east face and forced to bivouac on tiny ledges. By the time help arrived, three had perished from hypothermia.

The lower third of the wall was relatively easy until we came to the pendulum. I lowered Karl some 20 feet from the pendulum piton, and he swung out and danced repeatedly across the wall attempting to reach some small holds across a smooth face. Finally he succeeded, set up his anchor, and called for me to follow. Once by his side, I untied and pulled the rope through the piton. As I retied my knot, we knew that this climb had become serious. There was no way off but upward.

Several aid pitches followed and we surmounted the famous Rossi overhang, where we pondered the final 400-foot nearly vertical wall above us. We knew exactly what was ahead: several difficult pitches up a chimney system and then the infamous traverse known as the Ausstiegsriss, the exit crack. This last problem, my lead, began in an overhanging chimney. By stepping on Karl's shoulders and using direct aid I could barely see the beginning of the small crack, obviously a hand traverse, that led right some 30 feet across the smooth wall. I grabbed the lip and moved across, placing a few pitons on the way until I reached a good ledge for the belay. The climb was ours. On our return to the hut, we said goodbye to Aschenbrenner and trekked back to the roadhead, where Karl and I again parted ways.

Karl's studies were eventually over, and we assembled at the family home in Wolfern. We packed our rucksacks with all our gear, including light sleeping bags, a nylon bivouac sack I had made in California, and climbing equipment. Earlier, we had decided to travel by bicycle rather than by train, for this was not only cheaper but more flexible for choosing our destinations. Karl managed to find me a postal bike, which had only one gear and axle brakes. It was, he explained, the means for many climbers of Austria to get to the rocks before and just after the war. Small bags containing dry foodstuffs were suspended below the packs on the back of the bicycles. Each bike carried an extra 65 pounds of equipment.

I soon realized this trip was going to be troublesome. Even though hostilities in the German theater had ended four years before, travel restrictions still existed. Few cars traveled the roads owing to the shortage of gasoline, and the range of food was limited. Luckily, oatmeal and other grains, along with such delicacies as Speck (bacon fat) and sausages, were available. Karl was an expert in driving a loaded tour bike, but I was a total neophyte. After loading up, we bade farewell to his family and started down the road. I hadn't gone 500 yards when I attempted to turn around a curve, lost control, and crashed into a hedge. With inadequate weight on the front wheel, accurate steering felt impossible. A bad start, but I learned how to deal with this problem, and we rode on to our destination at the foot of the Dachstein. Here we climbed a beautiful peak called the Daumling by the southeast buttress. The climbing was spectacular: The ridge was solid limestone and offered a variety of intricate problems. Not only did we climb the route in fine style, we pioneered a more direct line to the summit on the last pitch.

On returning to the valley we pedaled to the next town and sent our rucksacks by public transport to a roadhead near the foot of the Grossglockner, at 12,461 feet the highest and most spectacular peak in Austria. Here we would start up the Pasterze Glacier to the Oberwalderhutte across from the north face. But first we had to negotiate the Glocknerstrasse, crossing a high pass in a thunderstorm.

As we rested at the entrance of a tunnel, a roar of thunder and flash of lightning occurred simultaneously. Karl was on his bicycle, leaning on a metal rail at the side of the tunnel, and nearly thrown to the ground. Fortunately no one was hurt. As we began the descent toward the hut, my overheated brakes failed and I landed in a ditch, a recurring problem during the next weeks.

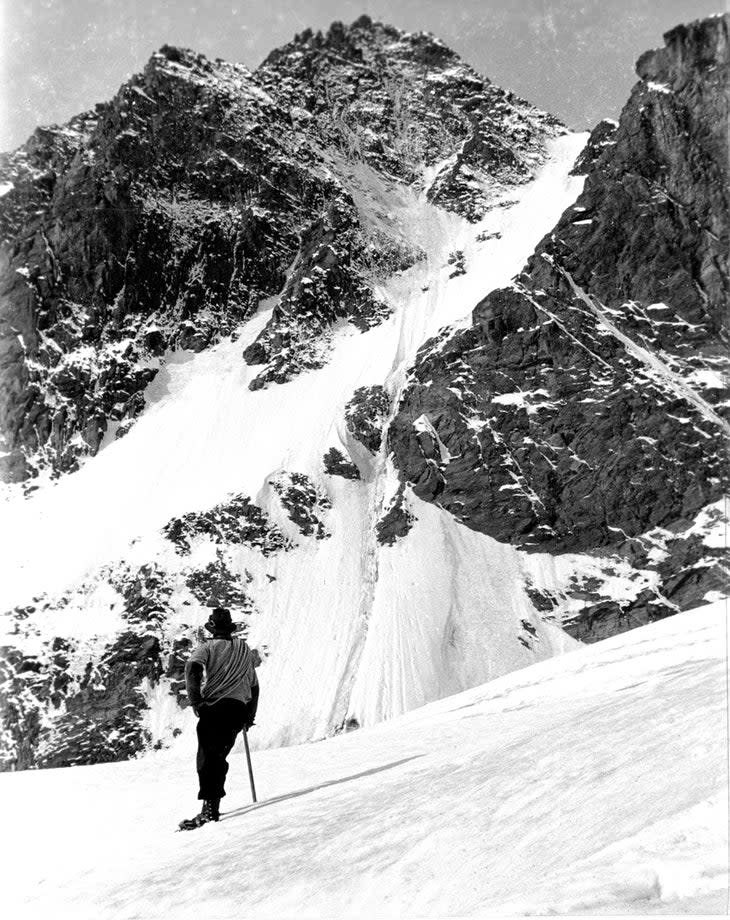

Karl had been interested in the north face of the Glockner for several years. The route was first climbed by Willo Welzenbach and Karl Wien in the fall of 1926, the year of Karl's and my birth. They took 11 hours, including four hours for the approach. Willo had an inclinometer and measured the angle of the lower slopes at 53 degrees and the upper rock wall at around 70 degrees, a rather normal configuration for Alpine faces.

Lugmayer under the north face of Grossglockner, the highest peak in Austria. He and Steck made an early ascent of this formidable alpine wall despite never having previously worn crampons. (Photo: Allen Steck)

At 3:30 the following morning we were rudely awakened by our pocket alarm. A fresh breeze had come up during the night, sweeping the skies of the lingering clouds, and the moon shone down on the north face, accenting the ridges and buttresses with startling clarity.

Karl clasped my shoulder, saying, "This is our world."

We tumbled down the stairs for a quick breakfast. Ice pitons, carabiners, crampons, warm clothes, bread, cheese and Speck went into our sacks along with a few other essentials, and soon we found our way down to the glacier. Once across and up the opposite slope, we stopped to put on our crampons and began to feel our way through the labyrinthine icefall that drained the snowfields under the north face. I was particularly cautious since, unlike Karl, I had never used crampons. We moved quickly through the shattered seracs and crevasses that formed this mysterious, unearthly crystalline world. The sun rose, and Karl's axe sparkled in the light as he hammered methodically into the ice under the bergschrund. Chopping some steps and hammering in an ice piton, he surmounted the top and soon set up his belay. The sun shone fiercely and small avalanches began to slide past. We had spent too much time in the icefall and now it was imperative to climb as quickly as possible. The crunch of iron on snow, an occasional shout, and the hissing of the avalanches were the only sounds that penetrated the silence.

As we approached the rocky buttress that led up to the summit, threads of mist wove around the top and dark clouds swept the glacier below. Originally, we had planned to climb the couloir to the right of the buttress, but it was full of debris slides, so we chose the rock face. It was now 2 p.m., with the buttress still ahead. Thunder rumbled to the south, and snow began falling. But the rock was good and we managed to move up fairly quickly to reach a spot beneath the summit ridge. I had just passed Karl and was leading up a chimney when a thunderous roar and blinding flash of fire lit up the air around us, and a jolt ran through our limbs. The sound died away and we stood, our ears ringing, listening to the buzzing of our axes.

"Schone Musik," said Karl, rather too philosophically.

The snow increased in intensity and we began to feel the bite of the cold. At the last rope-length below the summit, more lightning crashed onto the ridge, and the overwhelming precariousness of our situation forced a near-run past the enormous buzzing iron Gipfelkreuz (summit cross) on top. As we passed the Kleinglockner sub peak on our way to safety, another blast shook our bodies. Luck was with us that evening, as we eventually reached shelter, our clothes dripping with water, in the Adlersruhehutte on the ridge a few hundred feet below the summit.

Reaching the valley again, we retrieved our bicycles, began pedaling, reached Lienz in a dismal rainstorm, and continued on to Sillian, where we bought supplies just before crossing into Italy. We paused here and cast a fond glance back over the mountains of our beloved Austria. I say "our" with feeling, for in the course of the few weeks that I was with Karl or with his family, Austria had become, it seemed, as much a part of me as it was of Karl.

It seemed amazing this wall had been climbed, but the pitons arched up before our eyes.

Finally, we turned our eyes southward to the towering cliffs and spires of the Sexten Dolomites. My papers for the bicycle were in order, but my visa for Austria had expired. Fortunately, the border guard did not press the issue and let me cross into Italy, where the whole aspect and tempo of life changed before our eyes. A new language fell on our ears amid gaiety, laughter and untiring activity. Soon we reached the Dolomitenhof, where Karl knew the owner-manager, the guide Sepp Innerkofler. A group of students from a Catholic school in Milan had rented the inn, and since it was completely full, we slept in a nearby hayloft. Karl was a master at finding us such lodgings throughout our travels.

The next day, after finding a place for our excess gear and the bikes, we hiked to the Drei Zinnenhutte in about two hours. Here at last we had our first view of the fantastic, internationally famous north face of the Cima Grande, first climbed by Emilio Comici and the brothers Dimai in 1933. Comici was the most gifted Italian climber of his time, and he made many first ascents, classics still today, and was one of the first to develop technical climbing, including double-rope technique and slings for aid. His writings show a deep pleasure at simply being in the mountains, in close association with rock and sky, with sun, snow, cloud and storm. Sadly, Comici's career ended with a fatal rappel accident on a favorite crag. He was only 39.

By now Karl and I were very fit, but I still lacked experience in big-wall climbing, even though I had learned to climb in Yosemite three years previously. In those days it was unthinkable that Yosemite's enormous walls would ever be climbed. This 1,800-foot north wall of the Cima Grande, glowing with its characteristic yellow-orange color, seemed more overwhelming than any Yosemite cliff, yet it had been climbed in 1933! Karl and I stood admiring this monstrosity, our minds in turmoil. Karl, of course, knew from reading about Kasparek's earlier ascent what the climbing was like. The rock, like most of the Dolomites, was fractured, and well suited for pitons; in fact, many were in place.

After a couple of training climbs on nearby crags, we approached the first difficult lead early one morning. We stopped on a spacious ledge and looked up at the wall, the first 650 feet of which were overhanging. Icicles, falling from above, twisted and twirled in the air until they crashed into the talus a full 60 feet from the wall. It seemed amazing this wall had been climbed, but the pitons arched up before our eyes.

Karl tied in and started off. Using double-rope technique, he reached a piton some 15 feet above me and took tension while he surveyed the rock above. He called down in a rather surprised voice that he could see no more pitons for 25 feet and the wall was still quite steep. Then I saw him reach up and start to free climb with delicate balance on tiny holds.

Much higher, he clipped into the anchor pitons, and called down: "Al, I've got it."

With difficulty he pulled up the slack and gave me tension. I swung out, snapped the ropes out of the carabiners, collected them, and was soon by his side. I belayed as he traversed out to the right toward a crack that led up to the next ledge.

But we never got to see the ledge that day. Karl had climbed far above me when he ran out of rope before reaching the ledge with the next anchor. He was out of sight but I heard his call asking for more rope. I left my anchors and climbed up some 15 feet to where I found a small ledge to stand on. But there were no pitons and I had to use one hand on a hold above to keep my balance. I called up to Karl that I had set up a stance and could belay with one hand.

I remember clearly on our departure one of the priests on his knees begging us not to go up on that wall again.

He was in a difficult spot just below a bulge but with the pitons in place. With a determined effort he raised himself high, but as he struggled to reach a good hold, a rusty piton suddenly pulled out. Karl flew headlong past my shoulder. The rope jerked out of my grasp and the whole length of it went buzzing through the carabiners until only my counterweight stopped him. I looked down after that frightening moment and saw Karl climbing up to the starting ledge, rubbing his head. I managed to get to some secure pitons and rappelled.

"Yes, Al, I had some luck there," he said, with a somber look.

But he had suffered a sizeable cut on his head, so we hiked down to the Dolomitenhof. On the way we met three Swiss climbers who had witnessed Karl's fall. They had intended to start the climb that morning but spotted us on the wall and decided to watch through binoculars. At the Dolomitenhof, one of the students patched up Karl's wound and wrapped a bandage around his head. As the young woman put iodine on the wound, Karl went limp momentarily, but when Innerkofler produced a bottle of brandy he came around quickly enough.

The talk went on for hours until at 11:00 p.m. we realized that we had to get back to the hut in order to start the climb again the next morning. I remember clearly on our departure one of the priests on his knees begging us not to go up on that wall again.

By 10 the next morning we had reached the scene of the accident. Leading, I noticed that the rock was loose where the piton had pulled. I hammered the same piton back into a crack a little to the right and went up on tension to a tiny ledge, where I set up an anchor. Karl followed, still a bit dizzy, with a large bandage over the top of his head and tied under his chin. I again took the lead and we went on for several hours until reaching the famous Escalator Crack. This lead was about 100 feet long, requiring 25 pitons for direct aid. It was the pitch that had defeated many of the early attempts.

Twelve hours after we started that day, we reached the Aschenbrenner bivouac ledge, named after the hut keeper we met at the Stripsenjochhaus, who had completed the second ascent of the wall. We spent a reasonable night in our nylon bivouac sack and continued climbing, with Karl back in the lead, at first light. The face was much less steep now and we were soon on the summit basking in the sunlight.

We often discussed the fall, which I guessed was about 65 feet. Karl was spared more serious injury because of the overhang and the fact that he not only tied in at the waist, but also threaded the rope up and over both shoulders, which meant that when the rope came tight he would be facing upward. The piton that pulled, stamped with the letters KF, became part of my collection.

Almost three weeks after leaving Wolfern, after a fine ascent of the Civetta, we continued our journey to the Rosengarten Group. Near Predazzo I had another brake failure--I was slowly getting used to the crashes--but we eventually made it to the trailhead at the base of the Vajolet Valley, took a cable railway up a steep section and hiked to the Vajolet Hut, just across from the incredible Vajolet Towers. Pia Piaz and her husband were the hut keepers and they welcomed us with great enthusiasm; on seeing Karl's colorful head bandage they realized that he was the one who had taken the famous flight on the Zinne Nordwand.

The weather was excellent and our first tour went without incident, a traverse of the Vajolet Towers, starting with the unbelievably steep Delago Kante. Our stay at the hut was delightful, and when it came time to leave, the generosity of our hosts touched our hearts: Frau Piaz would not take a single lire from us for our lodging at the nearby unused Preuss Hut. The former hut keeper was her father, Tita Piaz, who had died just the year before in a bicycle accident. Soon we pedaled our way over a small pass to Bolzano, where we managed, in spite of the language difficulties, to send most of our gear to Aosta, close to Mont Blanc. We climbed on our bikes for the six-day ride.

Often we managed to sleep in small vicarages; one time, in a cornfield. Mostly we stayed in haylofts, which involved going up to a farmhouse and asking if we might lodge there. Once a bearded old man up in the barn behind the house screamed in French about the "Boche" and waved a pitchfork. The lady of the house probably would have let us stay, but he made it clear that German-speaking folks were not wanted. On the road we took our meals in small inns; sometimes a family might feed us. Often, usually at lunch, we would stop in villages at the local water fountain and eat a bowl of cereal.

We pushed our bikes over the highest pass in Europe, the 9,045-foot Stelvio Pass, and again I suffered brake failure on the descent. We slept in wood chips at a cabinet-maker's shop near the Swiss border ... cycled through Saint Moritz, then over some passes, then back into Italy, where we spent the night in a peasant's hayloft ... slept one night in a bicycle-repair shop while my brake was being fixed. One afternoon on our bicycles, Karl managed to catch the bumper of a slow-moving truck, but I was not quick enough and so didn't see Karl for a whole day.

Finally we reached Aosta, where again with language difficulties, we sent my bike back to Wolfern by train. A great relief swept through my body as I rejoiced in the termination of my struggles with it. Karl left his bike in Aosta and we were able to ride on the roof of an autobus to Courmayeur, where we found our way to the cable railway for the ride up to the Torino hut on the crest just east of Mont Blanc.

Fantastic thoughts surged through my mind as we entered this new granitic world. The view from the hut in the soft evening light was of a stupendous array of icy peaks, ridges and glaciers. What were we going to climb? The Walker Spur on the north face of the Grandes Jorasses was of great interest, but such an idea reeked of hubris because the difficulty and danger were far greater than anything we had yet experienced. We put it off, deciding on the traverse of the Aiguilles du Diable, five pinnacles on a ridge leading down from the summit of Mont Blanc du Tacul. The traverse went quite well, but I injured an ankle on the descent, so it took us extra time to get down the Mer de Glace and ultimately Chamonix. On the way, we looked up with great longing toward the Walker Spur, now only a dream.

Karl later recalled our first visit to a restaurant in weeks: "We were eating the slices of bread situated on the tables in baskets and put on mustard which also was to find on the tables. When all the baskets were empty, we discovered the place where the bread was ready for cutting into slices, we did this by ourselves. The owner of the restaurant watched us and he chased us away."

We went our different ways here: With Karl's pack I took the train to Zurich (he would pass through Zurich on his way back to Austria) to pick up my luggage and arrange transport to Genoa for my return to America. Karl returned to Aosta, where he would start a three-day bike ride to meet me in Genoa. While passing through Entreves, just above Courmayeur, Karl met Hermann Buhl, the Austrian mountaineer who would in four years make the first ascent of Nanga Parbat, who urged Karl to join him for a second ascent of the Aiguille Noire de Peuterey, a major peak on the south ridge of Mont Blanc. It was a challenge, but Karl declined, as he had promised to meet me in Genoa.

We met at the American Express office and took lodging in a small hotel overlooking the harbor. Sadness marked our last hours together. We talked of many things and of course the intense moments of the past six weeks. A subject we hadn't touched on much was our war experiences. I told him about being aboard a destroyer escort in the South Pacific; at the same time he had been a prisoner of war in England. He now told me the riveting story of his surrender to the British. At the age of 16 he made his first flight in a glider, eventually becoming a skilled glider pilot. But when things deteriorated for the Third Reich in 1944 he was reassigned to the infantry and sent to the front in northern Holland. The train in which he was traveling was savaged by a Spitfire attack and many were killed. The remainder of his unit was then sent close to the border of Belgium, where a British force was on the attack. In fierce fighting, he hid in a foxhole in a large marshy field as artillery shells and rifle fire crashed about. His unit realized its position had been given to the British by a local Flemish resident, and the order was given to relocate. Karl took off his helmet while digging his new foxhole and on picking it up discovered that a bullet had gone right through it. In the pre-dawn light he spotted a light vehicle loaded with soldiers coming his way, and the split-second after it passed he leapt up and jumped into the vehicle, parting the rifle barrels quickly to avoid being shot. The British soldiers were as surprised as Karl at this bold maneuver. He was 18. He spent the next two years as a POW in England and was glad that he had never fired a shot at the British.

Karl came down with me the following day to the dock and we said our farewells. We knew we would see each other again. Karl's last comment in his brief diary was: "Ich bin Allein."

Before meeting again 10 years later, we both married and started our families. I named my son Lee Karl Steck and he named his son Karl Allen Lugmayer. After Karl completed his studies, he took a position with Swissair at the Vienna airport and thus traveled at reduced cost to various parts of the world. He continued climbing; two of his more important ventures were the ninth ascent of the Eiger's north face and an expedition to the mountains of Peru. He would often come to California to visit. Karl and I celebrated our 80th birthdays at a lavish, festive party in Berkeley in May of 2006. My gift to him was the KF piton.

Allen Steck lives in Berkeley. The above story has never before been told in its entirety. In the photo below, Steck (left) and Lugmayer share a joint 80th birthday party in Berkeley, May 2006. This article first appeared in Ascent 2012.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.