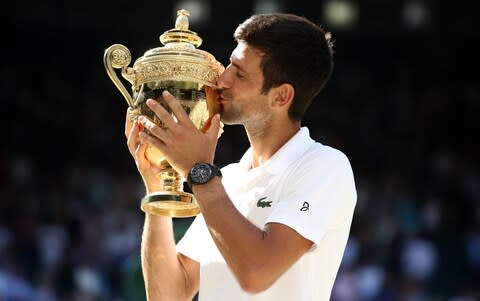

Novak Djokovic defends his Wimbledon title - still respected, still largely unloved

It was midway through his fourth-round match in Melbourne this year, as he struggled to subdue the obdurate Daniil Medvedev, that Novak Djokovic’s patience finally snapped. Sections of the Australian crowd were applauding his every error, as if willing him to crumble. Irked, if not deeply hurt, the Serb went through his repertoire of sarcastic responses, pulling faces, clapping along, and offering a mock thumbs-up. He was, he hardly felt it necessary to remind his tormentors, a six-time champion in their city. But he was clearly not feeling the love.

Ever since, Djokovic’s post-victory ritual, where he places both hands above his heart and extends them out to all four sides of the arena, has seemed more than a touch ironic. “The cup of love,” some have called it. Others have muttered that he looks like he is advertising a Wonderbra. The kindest interpretation is that Djokovic is having the last laugh on his detractors, lavishing them with the affection that they so stubbornly refuse to show him. More likely, though, is that he has simply spent too much time with Pepe Imaz, his on-off Spanish spiritual guru, who advocates having long hugs and establishing a connection with a “divine light”.

Nick Kyrgios – who else? – knows exactly what he thinks. “That whole celebration he does, it’s so cringeworthy,” the Australian said, in what his countrymen might call a “spray”. “I just feel he has a sick obsession with wanting to be liked – so much that I can’t stand him. He wants to be just like Roger Federer.”

The first point, naturally, is that Djokovic should refuse to take any lessons off an imp like Kyrgios. One has 15 major titles, while the other has failed even to advance beyond a quarter-final. But the more lingering question is whether Kyrgios, in his snide, sophomoric way, perhaps touched upon a deeper truth about the four-time Wimbledon champion. For a man holding superior head-to-head records against Federer and Nadal, and on course to eclipse the title hauls of both, he is startlingly unappreciated. When he prevailed in a thrilling five-set final over Federer in 2014, Centre Court reacted as if he had just shot Bambi’s mother. Across the net, he whispered to the Swiss: “Thank you for letting me win.”

On that occasion, Djokovic was deferential, accepting the public reverence for Federer. At the time, he clutched seven Grand Slam trophies. Now, he has more than double that, and one senses the lukewarm reception for his feats is starting to rankle. During his Wimbledon win last year over Kyle Edmund, patrons were grouching about his endless ball-bouncing routine before serving, prompting him to cup his hand to his ear in defiance. When he beat Federer in the Paris Masters final four months later, he opted not for diplomatic platitudes but for a primal roar of triumph.

If Djokovic still toils in the popularity stakes, it has not been for want of trying. Throughout his period of stunning success, he has doled out chocolates in press conferences, described Centre Court as “the cathedral of our sport”, spoken powerfully about his upbringing in war-torn Serbia, and even funded research at Harvard into the impact of conflict on children’s minds. What more, in the eyes of his doubters, especially in this country, does he have to do?

The explanation for Djokovic’s disfavour appears to be threefold. For one thing, he has simply become too “new-agey” for his own good. It is not just his connections to Imaz, but his soul-baring paeans for the benefit of his “Nole Fam”, his online army of loyal defenders. Having marked his fourth Wimbledon title by munching on the Wimbledon grass, he posted an Instagram message that ended “I love you, I love tennis, I love life”, with an emoji of hands in prayer. Professional tennis can be a gush-fest at the best of times, but this was taking it to Sally Field extremes.

Recently, there has also been a growing view that Djokovic holds too much power in tennis. He heads the player council and stoked widespread resentment earlier this year for his role in the toppling of Chris Kermode as chief executive of the ATP Tour. Indeed, resignations from the council are continuing. Who was Djokovic, ultimately, to have such sway on this issue? Where Kermode had enjoyed staunch support within the sport for his smooth running of tennis’ travelling circus, Djokovic did not even make a success of the Serbia Open when it was held under his name. He was prickly when asked last night about the infighting, asking: “Why are you singling me out?”

The third factor counting against him is surely the one he can do least about. In the age of Federer and Rafael Nadal, men’s tennis has difficulty accommodating a third kingpin when the other two are almost universally cherished. The aesthetic of his play is not always easy to warm to: where Federer has long beguiled by his single-handed backhands, and Nadal by his slashing, swerving forehands, Djokovic is the ultimate counter-puncher, a human backboard who cannot be broken down. Even when Federer, inspired by waves of Anna Wintour-led support in the 2015 US Open final, unleashed his full multitude of tricks, Djokovic found the answer, albeit not quite as elegantly, every time.

When he strides out for the traditional champion’s defence tomorrow lunchtime, Djokovic will find that his audience is polite, nothing more. The ovations will be saved for Federer, the Basel prince, later on. For Djokovic, that distinction is a galling one, but if and when he cements his status as the most decorated champion of all, he can put it down to the perversity of fan psychology. Yes, he has his flaws and his foibles, but in the final analysis, the obstinacy of his critics says rather more about them than him.