The fight of his life

AUSTIN, Texas – The menacing boxer had never looked so meek.

In the ring, he always wore black trunks, black shoes and an assassin's visage. But last week, in a federal courthouse, James Kirkland wore pale green clothes issued by the sheriff's department and the look of fear.

In April, less than two weeks before he was scheduled to fight for $300,000 and a likely shot at the world junior middleweight title, he was arrested for unlawful possession of a firearm by a felon. He had fought his way off the streets and onto the cusp of stardom and seven-figure paydays. But in a high-ceilinged courtroom last week, the man staring down at Kirkland had the ability to take it all away – and there was reason to think he might.

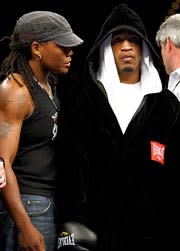

James Kirkland with trainer Ann Wolfe before his fight against Brian Vera in November, 2008 in Las Vegas.

(Getty Images)

Judge James Nowlin had been appointed to the federal bench in 1981 by President Ronald Reagan. He was a former Republican state representative sympathetic to the party's agenda. And in 2003, the Bush administration chose Austin as the site for a press conference renewing its commitment to the crackdown on felons with guns.

Conviction for the crime called for up to 10 years in prison.

By that time, Kirkland would be 35 and less equipped to help those depending on him – his young children, a disabled trainer and a gym of full of boxers trying to escape the crime-ridden streets of east Austin. Kirkland initially pleaded not guilty, then cut a deal with federal prosecutors.

Accepting a guilty plea, he took his fate away from a jury and put it into the hands of Nowlin. The sentencing guidelines, based on Kirkland's cooperation and prior criminal record, called for a prison sentence between 46 months and 57 months, at the discretion of the judge.

In 1995, a man on probation for aggravated assault when he was charged with unlawful possession of a handgun, made a similar deal with prosecutors. Nowlin sentenced the man to 57 months in prison.

Hands clasped behind his back even though the shackles had been removed, Kirkland stood across from Nowlin as the judge reviewed the terms of the plea agreement. He looked heavy, at least 40 extra pounds on his 5-foot-8 frame that was chiseled every time he entered the ring to fight in the 154-pound weight class.

Nowlin explained that under only limited circumstances would the boxer be able to appeal the sentence.

"Now is the time, Mr. Kirkland, for you to say anything you would like to say in your own behalf," Nowlin said. "I would be happy to listen to whatever you want to tell the court before sentence is imposed."

Defense attorney Jimmy Parks interjected.

Nowlin

"Judge, if we may, with the court's indulgence, we have three witnesses that we would like the court to hear," he said.

"Briefly," Nowlin replied.

Oscar De La Hoya, the legendary boxer-turned-promoter, was among the three witnesses coming to Kirkland's aid. The trio was prepared to testify about the special bond Kirkland had with young boxers, about how Kirkland stood to lose not only millions of dollars but a chance to positively impact troubled youth, and why severe punishment would indirectly punish others.

But they would have to work fast.

Nowlin was in no mood to dawdle, and so the defense team swiftly called the first of the three – Kirkland's manager, Michael Miller.

The tall man with salt-and-pepper hair made his way to the witness stand, placed his right hand on the bible and took the oath.

"Do you swear to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth?"

"I do."

The truth was, Miller and others should have seen this coming, but also had seen a side of Kirkland they hoped would soften the judge and help save the boxer's career.

It was September 2005 when Michael Miller picked up the phone in his San Antonio office where he works as a commercial litigator and part-time boxing manager.

"You don't know me," the woman on the other end of the line told him. "But I've got a fighter who just got out of prison."

The woman was Ann Wolfe, a boxer-turned-trainer, and the fighter was James Kirkland.

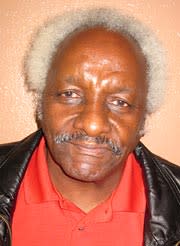

Michael Miller is James Kirkland's co-manager and testified on behalf of Kirkland.

(Photo courtesy Michael Miller)

Kirkland had finished serving his prison sentence for second-degree felony robbery and wanted to get out of his contract with promoter Lou Duva. More than anything, Kirkland wanted to fight and he thought his career was languishing under Duva.

Miller had a track record of getting boxers out of unfavorable contracts. Intrigued by the phone call, Miller in turn called Richard Lord, a longtime boxing trainer in Austin, in hopes of learning more.

"He's a tough kid but he's not going anywhere," Miller recalled Lord telling him. "He'll stay in trouble and he's got no direction.

"If you want to waste your time, get involved. If you don't want to waste your time, don't get involved."

Trouble or not, Kirkland was a southpaw with an 11-0 record. Miller decided to meet the boxer and Kirkland's two co-trainers, Wolfe and Donald "Pops" Billingsley. Soon after, he decided to get involved.

Within a matter of weeks, Miller had extricated Kirkland from the contract with Duva. He helped find a new promoter, and soon Kirkland returned to the ring and returned to form.

He scored one knockout after another, and by May 2008 he was 22-0.

Enjoying his winnings and an advance from Miller, Kirkland bought cars the way some people buy shoes. His fleet included a tricked-out Cadillac El Dorado, as flashy as the cross that dangled around his neck on a gold rope chain. He gave a car to Billingsley, the trainer who discovered Kirkland in a homeless shelter when Kirkland was 6, and gave one to Vanessa Walls, the mother of two of Kirkland's three children.

He continued to train in a modest gym that served as home to juvenile delinquents who, like Kirkland, saw boxing as a way to escape poverty.

"It's almost surreal," Miller said. "You know, the world sees him as a big, tough fighter but when he's outside the ring, he's the most playful young man that I can remember.

"… Of all the fighters that I've been involved with, James to me is the most special fighter that I've ever had. The reason being, he's the one that's really come from the bottom up."

Few understand that path as well as the next witness Kirkland's attorney called.

"Ann Wolfe, your Honor."

Her thin dreadlocks pulled back, Wolfe took the witness stand.

"I was bad in the streets when Pops got me," she said. "I went to the gym and I hate to say it, but James was the stinkiest little boy I had ever met, and it just seemed like he came from such horror that it was just like I was."

Donald "Pops" Billingsley, who co-trains Kirkland, found the boxer in a homeless shelter when Kirkland was only 6.

(Josh Peter/Yahoo! Sports)

Wolfe was homeless and 25 when she joined the gym and went on to win eight world titles. She became a hero in Austin and she took note of the young, hard-punching southpaw who showed so much promise.

Kirkland turned pro at 17, mostly because Billingsley thought it might help keep the boxer out of trouble. That proved difficult.

He was 11-0 when he was charged for forgery in 2003 after police found him in possession of six counterfeit $100 bills. Later that year, he was arrested for armed robbery after a store manager who'd been held at gunpoint picked Kirkland out of a police lineup. All of which made Wolfe even more inclined to help the troubled boxer.

During Wolfe's teen years, she served prison time in Florida for drug dealing. Kirkland reminded Wolfe so much of herself.

"James, like me, when we in the ring, we're going to fight to the death," she said.

She was more than willing to help Kirkland when he got out of prison in 2005 but had doubts about her role. Ailing after his third stroke, Billingsley decided it was time to hand over the majority of his duties to another trainer. He selected Wolfe.

"I can't coach," she protested.

"Yes, you can," Billingsley said. "Before it's over you'll be better than me."

Wolfe put herself through brutal training sessions, and she demanded the same from Kirkland. They flipped tractor tires through a field. They worked the mitts while wearing plastic sauna suits in the overheated gym. They did roadwork while pounding a heavy bag hanging from Billingsley's rundown truck.

"Whatever I asked him to do, he did," Wolfe said. "… He spoke to every single kid that was in that gym, and he made all of those kids feel like they was somebody.

"You know, it's like they missing out on a lot by him not being there. Last night they were like, 'What's gonna happen to James?' "

They weren't the only ones worried. So was De La Hoya, the last of the witnesses called.

Two years ago, Kirkland's camp got an unexpected call from De La Hoya's company, Golden Boy Promotions. They were looking for rising stars and signed Kirkland to a five-year deal that guarantees him three fights a year for no less than $150,000 a fight, according to Kirkland's manager.

In his two fights after joining Golden Boy, Kirkland scored technical knockouts. HBO expressed interest in a lucrative multi-fight deal.

"The prime years for a boxer are between the ages of 19 and 30 years of age," De La Hoya said. "I had an opportunity to do so much in that time frame, impact so many people, and be successful at it.

(Left to right): Oscar De La Hoya; Michael Miller, co-manager; James Kirkland; Cameron Dunkin, co-manager; and Ann Wolfe, co trainer. De La Hoya, Miller and Wolfe testified on behalf of Kirkland at the boxer’s sentencing hearing.

(Hoganphotos/Golden Boy Promotions)

"James Kirkland, yes, he is in that time right now."

De La Hoya said Kirkland had an opportunity to make millions of dollars and impact millions of people before a federal agent staking out a gun show in April found a loaded .40-caliber Glock in the center console of Kirkland's car.

"I'm very disappointed in him," De La Hoya said. "It hurt me because we do believe in him and we want to create something big. …

"I have to say that I put some of the blame on myself. I was too late to talk to Kirkland and take him under my wing because we just recently signed him, and we had to deal with other fighters. I want to take that responsibility."

With De La Hoya excused from the stand, the judge listened to final arguments.

The defense said Kirkland had been robbed earlier this year and bought the gun for self-protection.

Prosecutors did not dispute those claims, but said showing lenience just because Kirkland was an athlete would send a dangerous message to the community.

Speaking on his own behalf, Kirkland said he wanted a chance to make amends not only to his family but to the people who remained in his corner.

"There's no more slips," he said. "I don't have no more second chances and third chances. This is it."

Finally, it was in the hands of the judge.

Throughout the hearing, Nowlin kept courtroom observers off balance.

"It’s more difficult for this court to be as generous and as trusting of people like you," he said at one point, referring to Kirkland’s criminal record that includes at least one arrest in seven of the past eight years for what Nowlin described as "relatively minor offenses."

But he also remarked, "I want to do what I can to assist you …"

And then, "All right. Mr. Kirkland, the Court has reviewed the record in your case, including the information contained in this pre-sentence investigation report about your background, together with the information that you have presented to me through your statements and comments, and your lawyers and government lawyers that presented the case."

"… what you do with your life to a large extent has an effect on what I do in the future with regard to other people."

– Judge James Nowlin speaking to James Kirkland during sentencing

Kirkland stood still, ramrod straight.

A nervous energy filled the courtroom

Nowlin continued.

"… the Court is going to depart below the guideline range, and instead find that the appropriate sentence in your case, considering all of the factors that Court is required to consider, is a sentence of 24 months."

The mother of Kirkland's two youngest children turned to her aunt.

"Thank you, Jesus," she said.

One of the family's attorneys threw a celebratory uppercut.

Nowlin said he was impressed with the outpouring of support for Kirkland, and the three witnesses – Miller, Wolfe and De La Hoya – looked relieved.

The six months Kirkland had spent in jail reduced the sentence to 18 months. Good behavior could cut the sentence by another three months, and Texas law allowed the final six months of a sentence to be served in a halfway house. Kirkland could be out of prison and ready to fight in 10 months despite committing a crime that carried a maximum sentence of 10 years.

"I have taken a chance with regard to reduction of the sentence in your case, Mr. Kirkland," the judge said. "I am impressed by what you have done and what you can do with regard to young people who have had problems and difficulties growing up as you had.

"… what you do with your life to a large extent has an effect on what I do in the future with regard to other people. So, if you foul up out there, you're going to hurt somebody else who comes before me and gives me this same story. Do you understand?"

"Yes, sir."

"OK. Good luck to you."

"Thank you, sir."

And so a judge who could have all but ended Kirkland's career gave the boxer a chance to fulfill his promise – inside and outside the ring.