Meet the New Orleans Saints’ ‘athletic engineer,’ who’s helping keep NFL players like Taysom Hill on the field

That day a few years ago, when he walked into Alabama coach Nick Saban’s plush office, Matt Rhea felt the same kind of unsettled nerves he experienced when he was a placekicker attempting game-winning field goals as a young athlete growing up in Tooele, Utah.

“You find things that you don’t notice with the naked eye and you see trends over time. You need a lot of data. It’s one of those things that as I get older, I’m accruing more and more data.” — New Orleans Saints director of sports science Matt Rhea

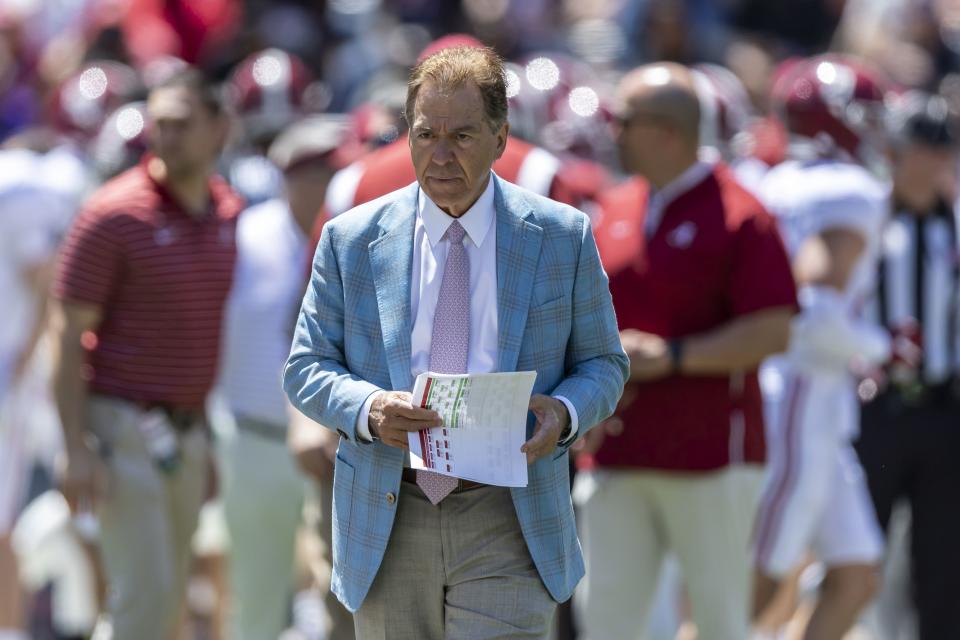

Saban’s corner workplace on the second floor of the Mal M. Moore Athletic Facility off Bryant Drive has been dubbed the “Oval Office” of Tuscaloosa. There’s a large wooden desk with a large Alabama logo embossed on the front. There’s Saban’s leather chair behind the desk. There’s a Hall of Fame’s worth of trophies and memorabilia throughout the room.

“His office is probably the coolest I’ve ever been in,” Rhea said.

That’s where Rhea, who’s established a reputation as an innovator in the field of sports science, was about to undergo an interview with the man who’s considered the GOAT of college football coaches. The man who’s won seven national championships.

Not to mention Saban guides the program that is widely regarded as the most successful in the annals of college football history.

Saban was looking for something different and Rhea had caught his attention.

Alabama’s strength and conditioning coach had left the program and Saban was intrigued by Rhea’s sports science approach. He sought an alternative to relying on traditional training methods.

“He decided to make a change in his strength and conditioning and wanted to move more into the sports science direction, which was really the draw to me,” Rhea said. “That was an opportunity that came up because a coach wanted to move more in the direction that I had been pushing.”

Rhea’s overarching goal is to prevent injuries and help athletes maximize their strength, speed and performance.

Sitting behind his massive desk, wearing reading glasses, Saban perused a stack of papers. Rhea would learn that those papers contained information that Alabama had unearthed about him, including talking to people that he hadn’t worked with or seen in a decade.

During the conversation, Saban glared at Rhea over his glasses.

Not surprisingly, given the fact Saban is a stickler for detail, the background check on Rhea had already been done. The interview was a formality, a process of Saban trying to figure out if Rhea would be a good fit for the program while trying to get to know him.

Rhea quickly realized that Saban had made his decision about hiring him before he entered that office. After that, Rhea relaxed a little bit and enjoyed talking to Saban.

“He asked very, very good questions,” he said. “It’s obvious that he’s trying to learn something and figure something out versus figuring out if he should hire you. I really enjoy those kinds of conversations.”

Saban ended up hiring Rhea, who spent two seasons at Alabama, and they built a strong relationship. Rhea was part of the Crimson Tide team that captured the 2020 national championship.

Rhea — who is known as Dr. Rhea because he earned a Ph.D. — has since moved on to become the director of sports science with the NFL’s New Orleans Saints. He has a wealth of experience helping athletes across many sports. In 2001, he started a consulting company, assisting NFL, NBA, MLB and NHL teams, International Olympic programs and college athletic departments.

During his career, he’s published almost 100 studies in sports performance enhancement and he’s lectured in seven countries.

Related

One player with the Saints that Rhea works closely with, former BYU star Taysom Hill, describes Rhea as a “mad scientist,” someone who digs deep into the well of data while forging strong, genuine relationships with athletes.

“It became very evident from the first time we met that his approach was unique and different,” Hill said. “It was all about getting the most out of my body. It’s entering our second year together and that’s his whole mindset. It’s the only thing he cares about.”

Rhea describes himself as an “athlete engineer.” It’s an analogy he draws from Formula One racing.

“The engineer is the guy that coordinates with strength and conditioning, sports psychology, nutrition, everything. If changes need to be made to the car, how certain individuals are doing on the pit crew, what drivers need for support, he’s the engineer,” Rhea explained. “He’s orchestrating the athlete development and performance priming process.

“That’s really what my role is. It’s figuring out what the athlete needs, what support he needs, to develop and flourish. Find the weaknesses, find the flaws and then coordinate a plan.”

And that’s exactly what Rhea is doing at the highest levels of football.

From placekicker to sports science

Rhea’s road to sports science wasn’t one he dreamed he would take as a youngster growing up in Utah, where he played sports, including soccer and football.

Short in stature, but highly competitive, Rhea graduated from Tooele High and served a Latter-day Saint mission to Chicago. He was a placekicker at Southern Utah University for one season.

“I quickly figured out I better make a living with my brain, not my body,” Rhea said.

At SUU, he discovered sports science. He became fascinated with the meshing of sports psychology and strength and conditioning and ended up earning a master’s degree in exercise science and physical education in 2001 and a Ph.D. in 2004 from Arizona State, with a focus on sports performance enhancement and injury prevention.

The topic of Ph.D. dissertation was “performance enhancement and injury prevention among firefighters.”

Why?

“There was a good connection with the fire academy, so it made research easier,” he said. “That was the start of the ‘tactical’ athlete approach for first responders.”

During his time at ASU, he fell in love with the research side of sports science.

Rhea and his wife, Kellie, didn’t have an end goal in mind of where this profession might lead.

“I never set a goal to work in the NFL,” he said. “For us, it’s been about the journey and the adventure of it.”

The Rheas had four of their five sons before he finished his Ph.D. As if all the years of postgraduate studies weren’t enough, the couple has moved 12 times since they got married.

“You talk about my wife holding down the fort and making sure everything was right at home,” he said.

Kellie was supportive of her husband chasing his dreams.

“Matt has never been one to settle,” she said. “He’s never content with ‘just good.’ He’s always looking for the next biggest thing. It translates to a lot of areas in life. Our family, how he works, how he works with the players. He wants them to be better as much as he wants his life and his career to be better.”

Rhea has paid his dues in the industry and has worked his way up. He was a football strength and conditioning coach for 14 years at the high school and collegiate levels. From 2016-17, he was the head of sport science at IMG Academy in Florida.

Mike Rhea witnessed Matt’s competitive nature growing up. But he never could have envisioned how his younger brother’s career arc would unfold.

“I knew whatever direction he went, he would be a real force,” Mike said. “He’s put the same fire and enthusiasm he had into the mental side of sports.”

Prior to his stop at Alabama, Rhea was at Indiana University for two years as the football program’s high-performance coordinator.

Rhea has enjoyed the challenge of helping football players, competing in a violent, dangerous sport, reach their potential.

“I love football. One of the things that drew me to football, from a professional perspective, was the speed of the game and size of the athlete, the contact involved. Injuries are part of the game,” he said. “I don’t even know if the human body was meant to do the things you’ve got to do in football. In my mind, one injury is too many. Unless the number is zero, I’m not happy.

“That’s a completely unrealistic goal, especially in football. To me, it’s the most challenging situation in sports to try to reduce injuries. It drew me to football. If that’s the biggest challenge, I wanted to see if we could have an impact on it.”

Sweet home Alabama

At the time Rhea was hired at Alabama, Crimson Tide fans had become frustrated with the high number of soft-tissue injuries. Saban wanted to address that issue by hiring Rhea and director of sports performance David Ballou.

The pair had worked together previously at the University of Indiana and IMG Academy.

Saban is known for his brutally difficult practices and all of the tests he’d have his players go through at the beginning of fall camp every year.

Rhea, of course, has his own ideas and philosophies about training. During his initial interview with Saban, Rhea was asked for his opinion.

“I remember thinking, ‘I could give him the answer I think he wants to hear and probably get this job,’” Rhea said. “Or I could give him the answer I think is right and see how he reacts. If he doesn’t react the right way, then that’s a good sign to me that this probably isn’t the right connection for both sides.”

Sure enough, Rhea gave him an answer — and Saban didn’t like it.

“It wasn’t that he didn’t want to do what I was saying. He started firing back. I had to convince him, which is how it went for the next two years,” Rhea said. “He said to me, ‘People come to me all the time about opinions that we practice too hard. We don’t need to do this test or we need to back off at certain times. But it’s always opinions.

“If you’re going to bring me an opinion, I have so many national championships by now that if someone’s opinion is going to win out, it’s going to be mine.’”

Rhea’s response to Saban?

“Coach, I’ll never come to you with an opinion,” he said. “I’ll come to you with some data. I’ll come to you with some experience dealing with data. I’ll come to you and show you the process I will use to provide you with meaningful ideas and suggestions for change.”

This job was the right fit for Rhea, too.

“I’m not the kind of guy that wants to be a figurehead so you can tell recruits you have this great sports science program, or so you can promote your program as being cutting-edge,” he said. “The coaches I’ve been able to work with have been great because I feel like I have some input. I’m not just a sports science guy.

“If I see something we need to change and do differently, I’m going to speak up. I don’t expect you to always do everything that I suggest but I want to feel like there’s some impact there. And if not, then it’s not the right situation.”

In Rhea’s first season, the Crimson Tide players embraced the new process and Saban said as a result, the program “cut down soft-tissue injuries by 50%.”

Because the team stayed healthy, it remained fresh deep into the season and Alabama won the national title in 2020.

“David (Ballou) and Dr. Rhea have done a phenomenal job really, and this has, I think, helped our program tremendously,” Saban said during SEC media days in 2021. “We wanted to make the change several years ago and brought several pro teams in with their old strength staff to try to change from the powerlifting to more of the velocity training used and the technology to actually test players daily, to minimize injuries but also to increase explosive movement.

“We increased explosive movement during the season by almost 5%, which we had not done for several years. So, we bought into the things that they do.”

Based on the recommendations from Rhea and Ballou, Alabama stopped doing traditional testing. How did Rhea and Ballou convince Saban to do things differently?

“If you want him to change something, you’d better have objective data to explain and suggest that the change needs to happen and then you better be ready for a fight,” Rhea said. “Not because he wants to be difficult, it’s because if you’re not willing to fight to convince him to change, then he might as well just keep doing what he’s been doing that’s won so many national championships. I absolutely loved that dynamic.

“Boy, he made me fight for a number of changes. At times, it was very challenging. If I had caved in and done what was easy and avoided the conflict, I wouldn’t have had much of an impact on the operation. There were some great, valuable experiences in terms of when you really believe something needs to change, you need to have a reason for bringing it up. You need to have a good justification for it and you better be willing to fight for it. When I left (Alabama), he said the thing that he appreciated most about me was that I wasn’t a yes-man.”

Dealing with hamstrings and ‘asymmetry’

Hamstring injuries are common in football and all sports. To reduce the risk of those kind of injuries, Rhea looks at all the variables that increase the risk. Those factors include strength, fatigue or an asymmetry (length discrepancy) from the right leg to the left leg.

“I have to find a test that will show me there’s an asymmetry,” Rhea said. “With technology, we have a system with cameras in the weight room that shows speed during different lifts. Through research, I know certain asymmetries cause a certain increase in the risk of an injury. I go and work with the strength and conditioning coaches to target that asymmetry.

“I’ve got to take a targeted approach in how we’re dealing with each individual athlete and what exercises they’re doing and how much exercising they’re doing. Then I track that asymmetry over time and make sure we’re reducing that asymmetry.

“That’s not the only thing. … Most of these are multifactorial. Even with hamstrings, there are seven different things that we look at just for a hamstring strain. While we’re not preventing all of them, the numbers go down. That’s been a trend. It’s not necessarily me, it’s the process that we’re employing that examines those risk factors, identifies the things that are increasing the risks and incorporating strategies to try to intervene and fix those factors before something bad happens.”

Rhea has learned to use science to meticulously track athlete performance and health.

“You find things that you don’t notice with the naked eye and you see trends over time. You need a lot of data. It’s one of those things that as I get older, I’m accruing more and more data,” he said. “That helps me at being even better at the job. In this sport and in this world, as soon as you start to get comfortable, you’re usually left behind. You have to stay on your toes and keep looking for new things to study.”

Working with the GOAT

Rhea said being on Saban’s staff was “probably everything you would imagine and then some. Incredibly intense. It was a very enjoyable experience aside from a never-ending grind. He treated me with great respect, which I really appreciated. In private, he was very different with me than maybe you see on the sidelines with everybody else.”

Rhea learned a lot from Saban, too, particularly when it comes to focusing on details.

Once, Rhea misspelled one word in a lengthy report. Saban caught it. He didn’t yell, but he told Rhea that was unacceptable, that if he was only double-checking his work, he needed to triple-check now.

“That attention to detail is something that really impressed me and really affected me in terms of how I operate,” Rhea said.

Rhea added that most of Saban’s former assistant coaches, even the ones that have had conflicts with him, say how much they appreciate the experience of working with him.

“That’s pretty impressive for someone who coaches and drives people so intensely,” he said. “Players and staff and coaches, it may burn them out and it may run them out but in the end, we’re all incredibly grateful for the experience and what we learned and got out of that experience. It’s very intense. But it was a positive experience. Winning a national championship and two SEC championships didn’t hurt either.”

That national title was won during COVID-19, a season unlike any other in college football history, as games were canceled or postponed and players and coaches had to adhere to strict rules and get tested for COVID-19 frequently.

“Working on controlling everything that you can control is kind of Nick Saban in a nutshell. COVID highlighted that and gave us a distinct advantage,” Rhea said. “Once you lock things down and you’re controlling everything you can control inside the building — that’s Nick Saban’s strength.

“We had 12 to 15 first-round draft picks on that 2020 roster. I’ve been around some incredibly talented teams. But that 2020 Alabama team was the best I’ve ever seen. Skilled players, really good coaching and circumstances that made the attention to detail even more important. I really enjoyed that experience.”

Graduating to the NFL

After the 2021 college football season, the New Orleans Saints offered Rhea a job as the team’s sports science director.

And with that, he took his first NFL position.

One of the reasons — the work schedule is different in the NFL. At Alabama, he got a total of 17 days off in two years.

“The thing that I was struggling with in college football is the calendar is unbearable,” he said. “With recruiting and camps, it’s nonstop. There’s never any downtime. When you get burned out, the first thing to go is your mind. For someone whose entire job is being sharp and creative and innovative, and understanding complex things, I started to feel that burnout set in.

“It’s not because I didn’t like coach Saban and not because I didn’t enjoy Alabama. It was just the grind of the schedule was too much. When New Orleans called, I saw it as a good opportunity to take on a new challenge. But also something that gave me more time in the offseason.

“We have two grandchildren now and being around them and not being able to travel in the offseason, I started to see things happening that I felt like I would regret not having more time. There were some doors open and close in that process that highlighted that God was making some things happen that would be better for our family. I’m seeing my family more this season than I did in four years of college football. It’s been worthwhile.”

When Rhea was hired, Saints coach Dennis Allen called it a “huge coup” for the team, according to the New Orleans Advocate. “We felt like it was just a slam dunk hire,” Allen said.

Rhea enjoys working with the Saints players, including Hill. While Hill didn’t know much about Rhea before he was hired, he quickly learned to trust him.

“That’s because I could tell he wasn’t interested in anything other than what was best for me. In my conversations with him, it was, ‘You’re 32 years old, here’s some data,’” Hill said. “‘We’re going to tailor these workouts that are specific for you.’ The NFL seasons are long. I can sit down with him and we can look at the data from last week and he’ll be like, ‘You got beat up.’

“And then we can tailor a program that week based on what I did on Sunday. It became what was best for me. It’s not, ‘Hey this is how we’re going to get the most out of your body.’ He took this approach of, what’s best for you is going to be what’s best for the organization, what’s going to be best for the team, because it’s going to help you perform the best.

“That’s a hard thing,” Hill continued. “It’s one thing to think that way but he spent the time and the energy to put that into practice, which is hard. It requires a lot of time. He collects a lot of data and sifts through a lot of data. He’s very genuine in that.”

Former Alabama players, who are now in the NFL, have credited Rhea for helping them improve.

Wide receiver Jameson Williams, now with the Detroit Lions, told the New Orleans Advocate that Rhea helped him become a faster player.

“I feel like he helped me gain some speed when I went to Alabama,” he said. “Every time I used to be with Dr. Rhea, he just helped me a lot, I feel like. It was speed training I’d never been on. He put me on some things I never knew about myself and also taught me more about my body.”

Another Crimson Tide wideout, John Metchie, now with the Houston Texans, also appreciated Rhea’s help.

“Doc brought a lot to Alabama. Doc is very special at Alabama and to a lot of the guys. Extremely special to me,” Metchie said. “He definitely brought a lot and definitely helped elevate the game for a lot of players there.”

‘All about family’

For all of his professional and personal accomplishments, Rhea said his wife, Kellie, is the “real superstar” of this story.

She was 18 when they got married. They’ve experienced a lot of changes, and a lot of exciting, unexpected moments.

“She’s been very supportive and very much invested in the journey,” Matt Rhea said. “If it hadn’t been for that, we would have stopped and settled down along the way. It was never about an end goal or destination.”

“Definitely quite an adventure,” Kellie said of their experiences. “You don’t really see how your life’s path is going to go. When you grow up in Tooele, Utah, you never imagine you’re going to work for the University of Alabama.”

The Rheas have relied on their Latter-day Saint faith as they’ve raised their family of five boys — Isaac, Jake, Ethan, Kelen and Karsten — and bounced around the country.

“All these things drew our family closer together. We always had Heavenly Father’s direction and blessing,” she said. “That made it a lot easier, just knowing that this was the path that Heavenly Father was paving for us.”

It wasn’t easy uprooting the family and moving to places like Florida, Indiana and Louisiana. But their strong bonds made the transitions easier. And they’ve forged lasting relationships during their various stops.

Before her husband accepted the Alabama job, Saban’s wife, affectionately known as “Miss Terry,” called her to “recruit me to Alabama.”

“She didn’t know I was already sold and I was packing my bags,” Kellie said. “She’s genuine and sweet, just like you see her on TV. She wanted to tell me about all the great things about Tuscaloosa.”

Kellie has appreciated that the coaches that Matt has worked for have at least one thing in common.

“They’re all Christians and they have a faith in something beyond,” she said.

They enjoyed inviting Alabama players over to their house and getting to know them and their children.

The Rheas have helped many they’ve come in contact with, even outside of sports, in quiet ways.

“He’s a unique combination of a brilliant mind and a lot of athletic talent. But he doesn’t want an ounce of recognition. He just wants to do his job, take care of his family and bless some lives,” said Rhea’s older brother, Mike. “He’s not the least bit worried about what people think of him. What people wouldn’t know is all the ways he blesses the lives of others that are very private. He’s constantly finding ways to help people with his resources.”

For Kellie, she’s enjoyed watching her husband excel at his job and the blessings and opportunities that job has provided their family.

“Matt doesn’t need to be in the spotlight. He doesn’t need the recognition,” she said. “So many good things have happened to us because we were willing to work hard and always look for the better and not to settle and to always put our family first. As great as it’s been, and as many amazing experiences that we’ve had, it’s all about family for us. That’s our greatest achievement.”

What will be the next adventure for the Rheas? That’s uncertain. They’re living in the moment.

“I absolutely love living in the South. I don’t know that I’ll ever leave now. I love the people, I love the Bible Belt culture,” Matt Rhea said. “Just some fantastic people. I’ve had some great experiences interacting with them. There are so many faith-driven people.”

From Tooele to Nick Saban’s office in Tuscaloosa, then to the NFL in New Orleans with the Saints, the Rheas are making a difference in the lives of a lot of people — including high-level coaches and athletes.