Meet Mungo Park, named for the 1874 British Open champ and the great-grandson of Willie Park, the first winner of the British Open in 1860

HOYLAKE, England — Dustin Raymond is an avid collector of golf memorabilia and he was searching online for buried treasures when he stumbled across an auction of vintage golf photographs from the 1800s.

He flipped through them and could detect that the majority of them were reproductions but a handful were originals.

“Holy cow!” he said he thought to himself. “That’s an original of Willie Park.”

He clicked “buy it now” for the collection of about 100 photos. When they arrived, he remembers thinking, “These don’t belong with me.”

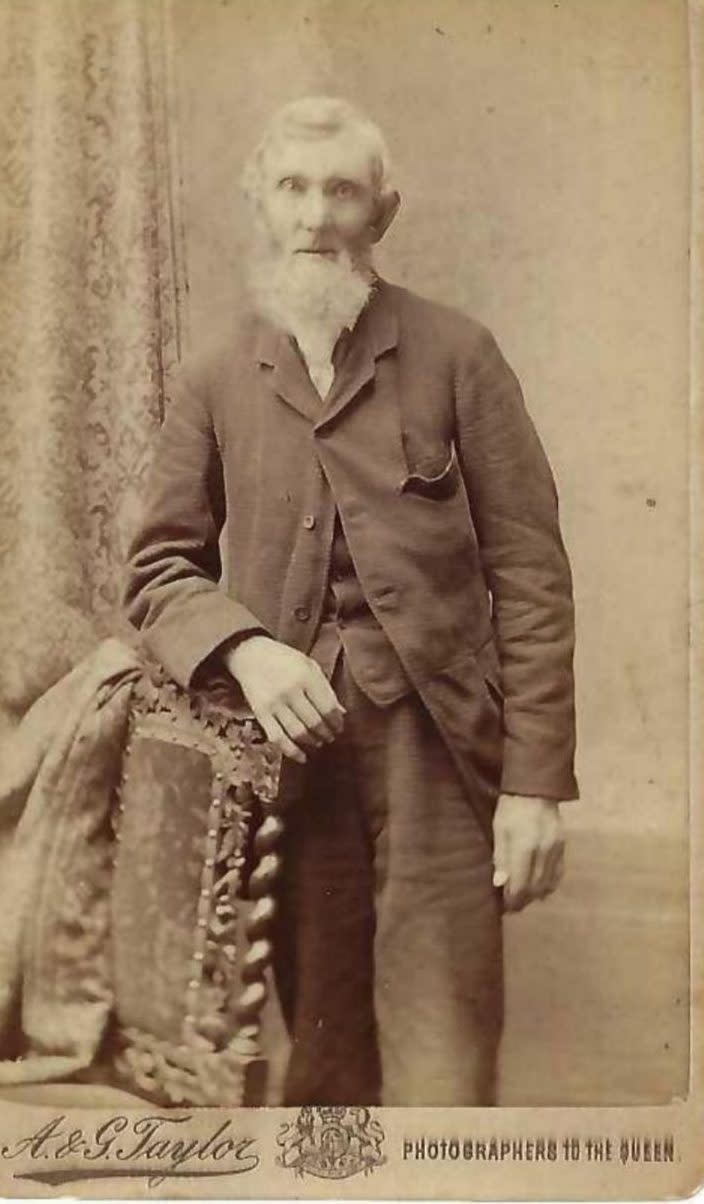

He posted some of the rare photos on the Golf Historian Society Web site, and one of the members suggested he get in contact with Mungo Park, the great grandson of Willie Park Sr., winner of the inaugural British Open in 1860 among his four titles, and named for his great-grand uncle Mungo Park, the winner of the Claret Jug in 1874. It turned out the photo that Raymond bought was rare, indeed, but it was of Mungo Park Sr., not Willie Park Sr.

“There are about six photographs we know of, of him, including that one, which has never been seen before,” Park said.

He could recognize the handwriting of a cousin on the back of the photos. Having them back in the family’s possession meant so much to Park that he asked Raymond what he could do to repay him for his kindness. Raymond simply wanted to meet him at the 151st Open and have a beer. On Thursday, Park drove five hours stopping to charge his electric car along the way, but he and Raymond, two men connected only by a photo that was approximately 150 years old, met during the first round at Royal Liverpool Golf Club. Yours truly snapped some new photos and sat with Park in the horseshoe grandstand surrounding the 18th hole.

Mungo Park Sr., winner of the 1874 British Open. (Courtesy Dustin Raymond)

Park has one of the great names in golf – Mungo is better than even Tiger Woods, right? For nearly eight years, he’s been working on a golf book on Musselburgh and the Park family’s place in the Scottish town’s reputation in the game, which Mungo contends should be better known as the true ‘Cradle of Golf.’ It’s where Mungo Senior won the first Open to be held at Musselburgh, shooting a record 159 to beat Young Tom Morris. That turned out to be his only Open victory. (Willie Park Jr. won two more titles — 1887 at Prestwick and 1889 at Musselburgh.) Mungo wrote in 2011 in an issue of Through the Green, the journal of the British Golf Collectors Society, that his great Uncle “never quite fulfilled his early promise. Like his brother and his nephew, and many after him, he turned to advising on the design and construction of courses, and the teaching of the game. He embarked on the peripatetic and sometimes precarious life of professional golf ‘architect/greenkeeper.’” In the census of 1901, Mungo Sr. was registered as a patient at Inveresk Poorhouse, and he died there in 1904.

Dustin Raymond, right, purchased a rare photograph of Mungo Park Sr., and returned it to family member Mungo Park (left), who is named for him. They met during the first round at the 2023 British Open at Royal Liverpool. (Adam Schupak/Golfweek)

Mungo also pointed a tenuous link between his family and the history of the Open at Hoylake. The 1967 winner, Argentine Roberto de Vicenzo, was a great friend of José Jurado, who had been his mentor and was the first to greet him when he returned home. Jurado had himself won seven Argentine Opens (El Abierto) in his career and was the first from his country to challenge the Europeans and North Americans on their own territory. As well as his Abierto wins, he finished in the top 10 in 4 majors (3 Opens and 1 US Open). “In Wikipedia it says that he began his career as ‘a caddie at the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews,’ which couldn’t be (literally) much further from the truth. In fact he was a caddie at the San Andres Golf Club in Buenos Aires, where he was taught by my grandfather, Mungo Park Jr.,” Mungo wrote. “My grandfather had designed and built the course there, and had himself won the first Abierto in 1905, and won again in 1907 and 1912. He was way down the field in 1922, when Jurado won his first Abierto, but it must have given him great satisfaction to see the success, and later career, of his protégé.

“There is of course another strong link to Musselburgh in that the original nine holes were laid out by Robert Chambers, who learnt his golf in Musselburgh as a child and was captain of Musselburgh Golf Club in 1855 and 1856. He was also a champion golfer, playing for the Bruntsfield Links Golfing Society when he won the first Grand National Tournament at St. Andrews in 1858. He went on to come 10th in the Open in 1861, and brought the Musselburgh Golf Club back to life after a 10-year period of dormancy, prior to the construction of its clubhouse and its centenary in 1874. The Chambers family are often associated with St. Andrews (where R Chambers Snr retired to) and with North Berwick where Robert Jnr built his grand house, and was also a member, but it is perhaps symptomatic of its neglected history that the family’s strong connection with Musselburgh and its clubs, over three generations, is rarely mentioned.

“It is fascinating how the stories of golf history interweave themselves with the social histories of the day.”

Here’s more about the name Mungo and the Park family history in the game from a previous email exchange between Mungo and Golfweek.

A rare photo of Mungo Park, winner of the 1873 British Open. (Courtesy Dustin Raymond)

Q: What's the origin of the name Mungo?

MP: Gaelic, Mung-hu, I believe. Kentigern, one of the early Scottish missionaries (518-614 AD) was known as Mungo. He is the patron saint of Glasgow.

Q: What does it mean?

MP: In Gaelic, I think it means ‘adored one.’ I try to convince my wife of this.

Q: How many Mungos have there been in the Park family?

MP: Four, including me. We are not related to the explorer of the same name, although my grandfather thought we were. The name came from my great great grandmother’s brother, Mungo Kerr, who was a toll keeper.

My niece, who is not actually a Park, named her second son Henry Mungo. Poor, kid. Hugh Grant is a Mungo. That’s his middle name.

Q: What has it been like going through life with the name Mungo?

MP: Interesting, particularly in England where there aren’t many of us around. Obviously, I got used to the name early, but others over the years have found it slightly more difficult. The only person against my being christened Mungo was my uncle … Mungo, but an unusual name has probably been more of an advantage than a difficulty. People don’t forget the name, which is useful.

Q: As a golfer, who was the best Park?

MP: That’s a tough one, as golf changed so much in the style and technologies that were current in each of the three generations. I guess Willie Senior in his prime was hardest to beat, but his younger brothers Davie and Mungo were also major players. Davie in particular is often forgotten, as he died relatively young (47), but some reports say that he was better than his older brother on his day. There was a fourth golfing brother, Archibald, who was also among the best, but gave up ball making and playing of the game as a way of living, when he came back from sea. He and his wife started a laundry. It was probably a more secure business move at the time.

Q: What pressure if any did you feel to uphold the Park name in Scotland?

MP: None. I was born and educated in England. I went to University in Edinburgh and was there for six years. It was then that I started to get slightly interested in the family history, but I was more interested in becoming an architect, [which became his trade.] … I won a competition for the clubhouse refurbishment, which was completed before they went back onto the Open rota.

Q: What family member schooled you in the intricacies of your golf family history?

MP: When I was in practice in London, my cousin’s husband, Archie Baird, asked me to print off a plan of a course designed by Willie Park Junior. Through him, I think, I was contacted by John Adams who wrote The Parks of Musselburgh. I found that pretty interesting, although there were some big gaps in it that puzzled me. My Dad filled me in on some of the Park history, but he hadn’t really engaged with it himself in any great detail, he had been too busy as a doctor. I started to explore the family history about 20 years ago, and discovered a wealth of stories from other Musselburgh golfers and club-making families.

Q: Do you love golf or do you feel obligated to be involved with golf due to your ancestry?

MP: I don’t play enough golf to consider myself a golfer, certainly not by Park family standards. When I do, it is a great joy and I get to see parts of the course that more competent golfers miss.

I live near Cleeve Hill, which is on common land high above the Severn valley. Built by a Musselburgh professional and Open Champion (David ‘Deacon’ Brown) and vested by Tom Morris to give advice and his seal of approval, it is common land, free draining limestone, cropped by sheep and associated with three Open champions – on a good day it is glorious.

I play for pleasure and good company golf on Cleeve gives me that. Gloucestershire has two other common courses, at Painswick and Minchinhampton, which are also a real delight.

Q: What golf myth of the 19th century do you feel is most wrong regarding the Parks or Morrises or the early era of the Open Championship?

MP: There is a myth that Allan Robertson was the best golfer in the world and was never beaten, which is simply not the case. His reputation and that of the other St. Andrews greats (and there were many) has been promoted by many generations of St. Andrews golfers, starting probably with Hugh Lyon Playfair, an extraordinarily energetic proponent of St. Andrews and really brought it into prominence.

But the St. Andrews story carries a weight of mythology around which tend to overshadow the histories of other places and their equally fascinating golfers and club makers. Montrose, Aberdeen, Perth and of course Musselburgh all had able and competitive players over the years, but we hear less about them.

I try not to be too partisan about Musselburgh, but a more balanced history of golf needs to recognize its significance in the development of the game in the middle of the nineteenth century. It is a fascinating history. Robertson, with Tom Morris and his son Tommy have been accorded almost religious status by some St. Andrews histories. While their history may be easily accessible, their stature obscures many richer stories of the time and presents a lop-sided view of history. We hear little, for example, about the Pirie brothers, from the generation before Robertson, or Tom Alexander, an older competitor of Robertson, and ball maker from Leith who moved to Musselburgh with the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers.

For 30 years, at least, Musselburgh was ahead of St. Andrews in the period of the game’s greatest growth. Leith and Bruntsfield in Edinburgh were arguably golf’s first home, Musselburgh its second home and St. Andrews its third.

The much-publicized rivalry between Musselburgh and St. Andrews, the Parks and Morrises were possibly more a feature of the news reporting of the day. As far as we can tell the two men enjoyed a relationship of mutual respect and enjoyed playing against each other, but that might have made poor copy for the newspapers of the time. It is interesting too, to see how many photographs show Old Tom and Willie Park Junior standing or sitting together, particularly after the death in childbirth of Willie’s first wife, Mary. It may not be significant, but it is reasonable to speculate that Tom had a sympathy for the son of his ‘great rival’, a feeling that might have been borne of Willie’s golfing ability but also of his tragic loss.