Can Kenny Dillingham, Arizona State football return to roots, wake ‘Sleeping Giant’ in NIL era?

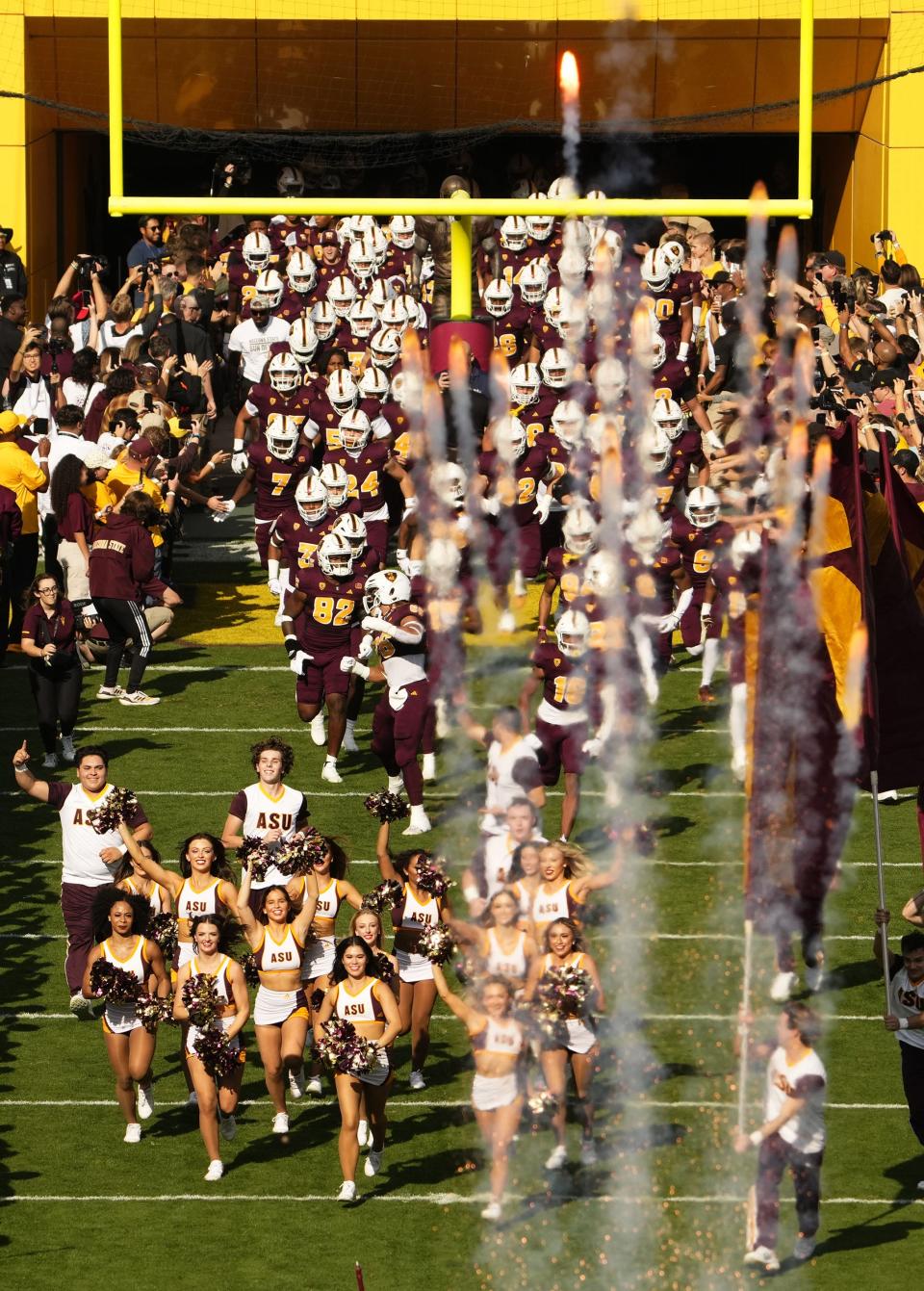

Arizona State football royalty returned to campus for the first time in years when the Sun Devils played Southern California in their last game as Pac-12 Conference rivals on a balmy September night at Mountain America Stadium.

Danny White quarterbacked ASU to a 32-4 record and victories in the first three Fiesta Bowls from 1971-73. He set seven NCAA passing records, also served as the team’s punter and played both positions for more than a decade in the NFL with the Dallas Cowboys.

In 1998, he was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame and had his number retired by ASU, just like his late father, Wilford “Whizzer” White, who led the nation in rushing yards and was the school’s first football All-America selection in 1950.

A family legacy. Father and son. Sun Devils for life.

But White, 71, a Mesa native and Valley resident, was not invited to the USC game by Arizona State.

He didn’t step on the field.

And his presence was never announced to the packed crowd, a rare turnout for the woebegone program the last several years under former coach Herm Edwards, who left the program mired in a recruiting scandal last season, and athletics director Ray Anderson, who resigned last week.

“It’s like coming home and somebody else lives in your house now and they don’t even know who you are, even though your name’s on the stadium,” White told The Arizona Republic, guests in a half-empty corporate suite rented by Dana Whiting Law, longtime supporters of Sun Devils athletics. “It’s just different. It’s like a different place. But actually, there’s spots where old pieces of skin and blood and sweat are out there.”

The sleeping giant

The Arizona State football program in the last half-century has gone from king of the Western Athletic Conference to Pac-12 also-ran, from overlooked outpost to major-market enigma, the weathered front porch of a proud university perennially ranked No. 1 in innovation by U.S. News & World Report, but long unable to tap the full power of its sprawling alumni base and gridiron roots.

Arizona State (3-8) hosts No. 16-ranked Arizona (8-3) for the Territorial Cup in the regular season finale at 1:30 p.m. Saturday on ESPN. Next season the archrivals move with Utah and Colorado to the Big 12 Conference, an opportunity to increase and solidify television revenue, expose the ASU brand to a larger swath of the country and, perhaps, wipe the slate clean.

ASU football has been mediocre at best for a decade, despite significant investment from taxpayers and student fees.

It’s been struggling to attract and retain talented players at the dawn of the NIL era, wherein student-athletes can profit from their name, image and likeness with marketing deals through third-party booster groups such as the Sun Angel Collective, which first-year head coach Kenny Dillingham has called “80%, 75% of recruiting.”

And it’s been struggling to earn support from one of the largest alumni bases and metro areas in America, disenchanted by the on-field product and a protracted NCAA investigation for allegedly hosting illegal recruiting visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Beyond the embarrassment, the scandal has resulted in massive staff and roster turnover, a self-imposed bowl ban and uncertainty about potential additional sanctions, including scholarship reductions.

Early signing day for college football is Dec. 20.

“We’ve got to step it up and get rolling at a rapid, rapid, rapid … rate in this next three weeks to one month,” Dillingham said last week about NIL. “We’re getting better. We’re competing. We need support. We need help. We need to ‘Activate the Valley.’”

Not the foundation, but a multiplier

Gregg Brewster is a fifth-generation Sun Devil, a member of the Arizona Board of Regents, the ASU Board of Trustees and the immediate past chair of the ASU Alumni Association board of directors.

He believes the Sun Devils must return to their former grandeur and NIL is the path to get there.

“If ASU starts ripping off nine, 10 wins a year, what does that mean?” Brewster said. “Well, that probably means ESPN College Gameday is coming. That means national exposure. That means other kids looking at it and saying, ‘Wow, I love the sun and I love their engineering program,’ and, ‘Wow, they’ve got a winning football team, which makes my fall even that much better.’ Or basketball, ‘Wow, they go to the tournament every year.’ Those are important things.

“The academics, the research and all that goes with it are most important. But you know what puts people in this university at a faster clip than just a great engineering program? Have a great engineering program and a winning football team.”

Last year, the Sun Devils lost nine games for the first time in school history and averaged their lowest attendance since 1968, before Danny White followed in his father’s footsteps.

Edwards left midseason with a $4.4 million buyout. This season, Anderson announced a self-imposed bowl ban in August, crushing morale just days before Dillingham’s debut.

Anderson, 69, resigned Nov. 13 after nearly a decade in the role, citing his age and the “number and magnitude of changes in the college sports landscape.”

His departure, coupled with a 17-7 victory against UCLA at the Rose Bowl, spurred a wave of donations to the Sun Angel Collective, which doubled its monthly membership last week, executive director Brittani Willett told The Republic. She declined to disclose membership numbers or financials, citing competition with other schools’ collectives, a common practice in the NIL space.

These booster groups are allowed to employ student-athletes and connect them with businesses and nonprofits, following a Supreme Court ruling that in 2021 ended the NCAA’s prohibition on athletes profiting from endorsements.

Arizona State’s advantage — and challenge — is leveraging economy of scale.

“How do you get a $20 donation out of 600,000 alumni?” Brewster said. “The power is in the numbers. How do we support NIL on a mass scale and just try to get $20 to $100 out of people annually? That could go a long way to playing the game the way the game is being played today.”

Rashada legacy: 'A lot we can tap into here'

Jaden Rashada is the son of a Sun Devil, just like Danny White. He was one of the top high school recruits in the nation this year, a blue-chip quarterback with his pick of major college football programs.

He’s also a poster child for the perils of the NIL space.

ASU was his childhood dream school, but Rashada ruled out signing with the Sun Devils because of the uncertainty surrounding Edwards’ tenure as coach and the possibility of NCAA sanctions, his father, Harlen Rashada, told The Republic.

Jaden Rashada, who signed his first NIL deal in high school, committed to Miami, then signed with Florida after the Gator Collective offered him nearly $14 million.

After the first payment fell through, Jaden Rashada, feeling betrayed, was released from his letter of intent, his dad said. He visited Texas Christian, then signed with ASU, comfortable with the relationship he built with Dillingham while the new ASU coach was the offensive coordinator at Oregon.

“There were probably a handful of coaches when we were on the recruiting trail who would find out, ‘Hey, you’re his dad, you went to Arizona State,’” Harlen Rashada said. “And literally, I’ve heard the term ‘sleeping giant’ maybe about four or five times from head coaches at prominent schools that have that outside respect for what we have here. There’s a lot we can tap into here. The question is when. The question is how.”

Jaden Rashada led the Sun Devils to a 24-21 victory over Southern Utah in the season opener, then took a helmet to the knee the following week in a loss to Oklahoma State, aggravating an old injury from high school that has since been “cleaned up” with a minor surgery, Harlen Rashada said.

Jaden Rashada will redshirt this season, maintaining four years of NCAA eligibility.

He has signed with the Sun Angel Collective.

“I think it’s wrong to take a pay-for-play attitude about it, because that’s not what it is,” Harlen Rashada said. “Every one of these kids have value to the university. You’re selling tickets, you’re bringing in people. These kids have the ability to be influencers in your community. Some of these kids, you can put on the face of your business. They have a lot of value that’s not just between the lines. And how you harness that and how you approach that is a huge factor in the direction your program goes. If you don’t embrace that, there’s someone who does.”

'A business decision'

Three attorneys at the Dana Whiting Law firm, all ASU graduates and boosters, met a week before the season to discuss their longtime support of the Sun Devils.

The company was entering the final year of its marketing contract with ASU and considering whether to keep its advertising and suite at the stadium, which last year reported the lowest attendance since 1968.

Nearly a decade ago, the law firm had a banner at the 50-yard line. But the group has dialed it back, their annual return on investment often at odds with the school’s valuation, their negotiations always factoring the football team’s performance and expectations.

“To us, it’s a business decision,” Matt Dana said. “We all love ASU. All three of us graduated from there. All five of my kids graduated from ASU. We are Sun Devils. We love them. But we’re businessmen. It’s got to be a two-way street.”

The trio agreed they would always keep season tickets. They have four apiece.

They were sad about the demise of the Pac-12, excited about joining the Big 12 and split on the merits and big-picture impact of NIL.

“Inherently, I’m not opposed to it,” Trevor Whiting said, “because I do think that the institutions exploit the name, the likeness of those amateur athletes and they should be able to tap into that. But I don’t think there’s any thought that it’s to level the playing field.”

The NCAA bans collectives from using NIL earnings as recruiting inducements, though such payments, along with a change to transfer rules that no longer require student-athletes to sit out a year when switching schools, have combined to bring a form of free agency to college sports.

“How do you get a kid to come here?” Dana said. “If it’s ASU or somebody else, if he can’t get a better NIL deal here?”

“If he’s a better football player, he’s not going to get a better NIL deal here than he will at Alabama,” Whiting said. “It’s a marketing deal, so the ones that are going to be more marketable are the better players. And you might miss on prospects, on the evaluation of the talent. But Alabama, because they’ve been better at the product that they put on the field forever, they get more money, they get more donors. Their NIL fund is bigger.”

Todd Smith noted the power of maintaining traditions and the local excitement from ASU returning to Camp Tontozona, after a four-year absence, for a weekend of preseason practices in Payson.

“We want them to embrace stuff like Tontozona,” Smith said. “Danny White should be a local hero. Everybody should know his name. And ASU should be putting him up on the board every time he goes to a game.”

“The Kenny Dillingham hire is probably somewhat of a nod to that,” Whiting said. “They’re acknowledging he’s an ASU guy. But ASU football has never panned out under anybody’s watch since Frank Kush, and ASU has been known forever as a ‘Sleeping Giant,’ and it’s ‘who can wake it up?’ Can it be Kenny Dillingham? And if so, then Ray Anderson will get some credit.

“But we were joking the other day: Maybe ASU’s not a sleeping giant. Maybe it’s a dead giant. It’s never going to wake up.”

Sun Devils for life

The ASU Alumni Association, the Sun Devil Club and Sun Devil Athletics hosted the annual Legends Luncheon the day before homecoming at the Omni Tempe Hotel.

This year, the event honored the 1971-73 teams coached by Kush and quarterbacked by White. A ballroom brimmed with ancient warriors. ASU had lost six consecutive games, including a valiant 15-7 defeat the previous weekend at No. 5 Washington.

Dillingham stepped to the front to address the group.

“We have practice here in about 20 minutes and they said, ‘Hey, can you come over and talk?’” Dillingham said. “I’m like, ‘Yes! Are you kidding me? This is where we’re trying to get to.’ The pinnacle of ASU football is in the room. Right here. And it wasn’t easy. I wasn’t at you guys’ practices. I can only imagine. But I assume they weren’t easy.”

The room erupts with laughter.

He’s 33, young enough to be their grandson.

“I assume there was a lot of yelling. A lot of this,” Dillingham said, knocking his knuckles together. “Right? But a lot of camaraderie at the same time. Because everybody is in the room today, right now. And when I got this opportunity to come back home — this is my dream job.”

Dillingham outlined his path from tossing a football in the parking lot as a boy on Sun Devils game days during the Jake Plummer era, to attending ASU and being an offensive assistant under Todd Graham, to becoming the offensive coordinator at Memphis, Auburn, Florida State and Oregon before returning to the Valley, his alma mater naming him the youngest head coach in major college football.

“I’m born and raised here,” Dillingham said. “My wife’s born and raised here. We’re both Sun Devils. My brother went to school here. My one brother got lost and went down south. But he lives in California now! We kicked him out of the state!”

The men howled with delight.

“My sister went here, my brother-in-law went here, my father-in-law went here, my mother-in-law went here. I’m through and through ASU to the core…” Dillingham said to applause.

“’Sun Devil for life,’ is something everybody in this room can relate to. It’s something that you can relate to that our same player can relate to, that a player 10 years from now can relate to. And it’s on the walls in our building. It’s what our entire program is built around. … Because I want people, when they come back and they walk into our building, to feel like it’s your building. And I feel like there’s a bit — and I’m just being honest — there’s a little bit of a disconnect or there has been between the comfort level.

“Why don’t you guys come out to practice?”

Dillingham scanned the room, both welcoming and challenging some of the greatest players in program history to lead the charge, explaining how their involvement can inspire the generations of alumni who followed them to get involved.

This is part of his vision to Activate the Valley.

“Our practices are open to any alumni, any day, whenever you want,” Dillingham said. “You just show up. You can bring your grandson. You can bring your wife. You can bring a friend. Bring whoever you want. You can just show up to practice. Because I want our players to see success.”

Sun Devil for life.

“It brings everybody back into the fold,” Dillingham said, “and that’s what I think is the secret sauce in any program. Are the people that have done it, and are the people from the past, are they still here in the present? Not just because we said we’re going to honor you with this one event. Right? Of course, we’re going to be here for this one event. But is there enough connection to the program?

“And what can I do to get you guys here? To feel that connection? To not just watch the games and cheer, but drive from California on five Saturdays, because you want to line the locker room and watch our team take the field? …

“I want that involvement here. And I’ve been at places where they’ve had it. …

“We’ve got to show our players and our current roster that Sun Devil football matters.”

'You can't do that today'

Pro Football and College Football Hall of Fame cornerback Michael Haynes, one of five Sun Devils whose number is retired by the school, and Kevin Woudenberg, a defensive lineman for the Sun Devils in the early 1970s, reconnect in a hotel hallway.

Fifty years ago, they helped put ASU football on the map.

“Back in those days, in my era, we were like the only game in town,” Woudenberg said. “The Suns were barely getting started. There was no DBacks, no Coyotes, no Cardinals. And then since we won, it was an easy draw and it was an easy connection. Everybody wanted to be with a winner, and ASU was always a winner, year after year after year.”

The Sun Devils amassed nine conference titles and a 6-1 record in bowl games with Kush at the helm from 1958-79. He twice went undefeated, was named the 1975 National Coach of the Year and in 1995 was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.

The field at Mountain America Stadium has long been named in his honor.

“It starts at the top,” Haynes said. “Coach Kush didn’t have the greatest players ever. But he did have a lot of good ones. And we just played together as a team.”

“We were mentally tough, too,” Woudenberg said. “We were not allowed to lose. That’s true. Because we’d pay the price the next week in practice.”

Arizona State had won 21 consecutive games over three seasons when the streak ended with a 24-18 thud at Oregon State in 1971.

“We got on the plane that next morning, we came back to Goodwin Stadium, which was the old practice locker room,” Woudenberg said. “We scrimmaged that afternoon on Sunday! And you know what? We never lost the rest of the season. And the next game, we hung 60-plus points on New Mexico. We had 42 by halftime.”

“I wasn’t here in ’71,” Haynes said. “But we had heard about that. Because a lot of those guys were still on the team in ’72.”

“Remember when we went to Camp Tontozona?” Woudenberg said. “We were up there for about two weeks. And we scrimmaged in the morning, we did shorts right after lunch and then we scrimmaged in the afternoon.”

“Three times a day,” Haynes said.

“And we ran and we ran and we ran,” Woudenberg said. “And this is not for two or three days. This is for two weeks.”

“But you can’t do that today,” Haynes said.

The conversation shifts to the six-game losing streak, to the NCAA recruiting investigation and fallout, to the demise of the Pac-12 and joining the Big 12 and NIL.

“It’s got to at least be in the ballpark of other places,” Haynes said. “And if you can’t get the money, then it’s got to be on that coach’s personality. Players just have to believe in that coach. He’s got confidence, a long record of winning, all that kind of stuff. And if you don’t have it, then tap into the guys that do have it and ask them to help you.

“Why would we help you? Well, somehow, we have to benefit too. And I benefit by saying, ‘I went to Arizona State. Man, those guys are national champions.’”

Booster, alumni, fan support redefined

ASU gave its athletics department $57.9 million in institutional support in fiscal 2021 — 10 times more than the year before and more than any other public university in the U.S. — plus another $11.3 million in student fees, which covered about half of the Sun Devils’ athletics budget at the height of the pandemic, according to the Knight-Newhouse College Athletics Database.

ASU provided another $26.4 million in institutional support and student fees in 2022, the second-most in school history.

In August, ASU sold naming rights for Sun Devil Stadium, rebranding the venue as Mountain America Stadium, and escaped the crumbling Pac-12 for the Big 12, beginning in 2024.

The Big 12 media contract with Fox and ESPN pays schools an average of $32 million per year until 2031, far more than ASU made in the Pac-12 but only about half of what Big Ten and SEC teams command.

None of this money factors into NIL.

“People get into the whole TV contract side of it and where it’s going to go in the future and I get it,” Harlen Rashada said, “but right now, you have the chance to get communities and business owners and alumni behind your athletes in a different way. And it’s not so much about money. It’s about support.

“Because what NIL really says is what type of support do you have for your program? And if you can speak to that, that’s great. Because at the end of the day, these guys are going to graduate here and be alumni here too.”

The top 20 players across all positions in the Pac-12 averaged about $77,000 in NIL income in 2022, while those in the Big 12 averaged about $149,000, according to information that NIL company Opendorse shares with collectives. These booster groups are believed to account for about 80% of the money in NIL.

The Sun Angel Collective, which operates on the Opendorse platform, has applied for 501(c)(3) nonprofit status and is awaiting determination, Willett said.

It accepts annual, monthly and one-time donations, as well as inquiries from organizations seeking to partner with ASU athletes.

“There are some five-star defensive guys that are right now getting a million a year in collectives” at other schools, Harlen Rashada said. “So there’s a lot of stuff going on that people don’t know about, because a lot of those numbers are private and a lot of those things are kept where they need to be for the sake of your roster. And that’s a good thing. But it’s happening.

“There are programs that are light years ahead of us right now with what they’re committing to do to build and protect their athletic programs. There’s just a lot of programs that are ahead of us. And can we catch up? For sure. But if you want to catch up, you’ve got to run a little faster.”

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: ASU football could return to roots, wake ‘Sleeping Giant’ in NIL era