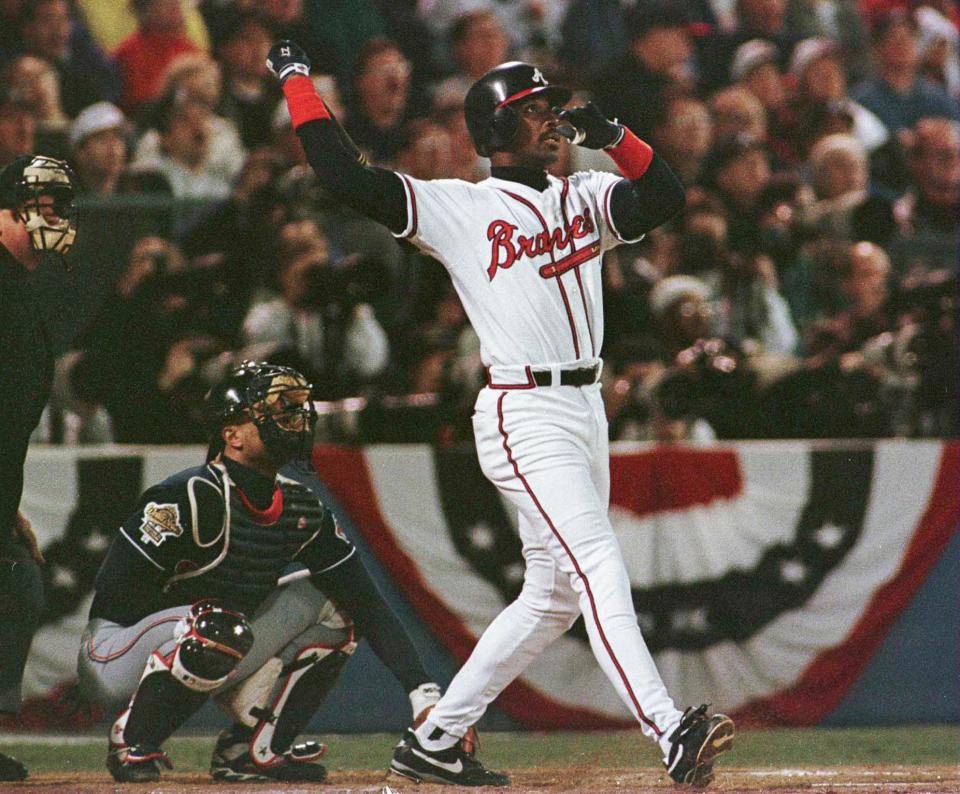

'What a Hall Famer is all about': Beloved by all, Fred McGriff's peers talk 'Crime Dog'

COOPERSTOWN, N.Y. — If Fred McGriff flipped his bat or trash-talked, he might have been a first-ballot Hall of Famer nearly 15 years ago

If not for the 1994-1995 work stoppage, McGriff would have eclipsed the magical 500 home run mark and waltzed into Cooperstown.

Well, all that matters now is that McGriff is in, a unanimous selection by the Contemporary Baseball Committee after being snubbed on the writers’ ballot, and will be inducted Sunday into Baseball’s Hall of Fame along with third baseman Scott Rolen.

“He’s in, and that’s all people will remember," former home-run king Mark McGwire told USA TODAY Sports. “It doesn’t matter if you get in on the first ballot, the last ballot or through the era committee, you’re a Hall of Famer. It’s like it doesn’t matter if you’re first in class as a doctor or last in class as a doctor, you’re still a doctor.

“Fred is a Hall of Famer. He’s one of the best to ever play the game. That’s all that matters.’’

The stats will show that McGriff hit 493 home runs, drove in 1,550 runs, had a .509 slugging percentage and was a career .303 hitter with a .917 OPS in 50 postseason games.

He hit 30 or more home runs 10 times in his career, including seven consecutive years, but never more than 36. He finished in the top 10 in MVP voting six times, but never higher than fourth. He was a five-time All-Star, and was the 1994 All-Star MVP. He was a World Series champion in 1995 with Atlanta.

“I wanted to be like George Brett, he could do it all,’’ McGriff told USA TODAY Sports. “I was in the Blue Jays’ minor-league system when the Royals played the Blue Jays in the 1985 playoffs, and he started hitting home runs foul pole to foul pole. It was awesome.

“I wanted to be a hitter just like him."

Ten years later, McGriff was leading Atlanta to its first World Series title, hitting .333 with six doubles, four homers and nine RBI that postseason.

“People don’t talk enough about just how good of a hitter he was in the postseason," said Greg Maddux, a Hall of Famer and McGriff's teammate in Atlanta.

Still, to simply judge McGriff by his numbers is like saying that a Porsche you see racing along the highway has a great sound system.

You’ve got to look under the hood.

If you really want to know what kind of player he was, what he meant to his peers, his teammates, opposing managers and GMs, pull up a chair and listen.

The teammates

Gary Sheffield

Sheffield, who hit 509 home runs in his 22-year career, was a nine-time All-Star, five-time Silver Slugger winner and World Series champion, said he never would have had his stellar career without McGriff.

He was traded in the spring of 1992 to the San Diego Padres after being labeled a young malcontent in the Milwaukee Brewers organization. When he arrived, McGriff was there to greet him. Sheffield, the nephew of Dwight Gooden, was from St. Petersburg, Florida. McGriff was from Tampa. And McGriff took it upon himself to become Sheffield’s mentor, a big brother.

Sheffield rented a house next door to McGriff and his family in Poway, Calif. They talked baseball non-stop. They talked about the maturity it takes to stay in the big leagues. They talked about being a professional at all times.

Sheffield, after hitting .194 with a .597 OPS in his final year in Milwaukee, nearly won the Triple Crown in his first year in San Diego. He hit a league-leading .330 with 33 homers, 100 RBI and a .965 OPS, finishing third in the MVP race.

“I don’t have the career I had without Fred, it’s that simple,’’ Sheffield told USA TODAY Sports. “We were like brothers. I couldn’t get to where I was without Fred. Fred could have played without me and done well, but I sure couldn’t say the same thing.

“I needed that guidance. I needed to mature. Fred was there for me. He helped me in so many ways.

“That’s why I’m just so elated. When he made it, I told him, 'Man, that made me feel better than anything. It feels like I got in there. I know what type of person you are, how hard you work, how dedicated you are in this game.' "

Greg Maddux

Maddux, the Hall of Famer and four-time Cy Young winner, remembers the frustration and angst of the 1993 season.

Atlanta was nine games out of first place and going nowhere, when GM John Schuerholz acquired McGriff from the Padres for three minor-league prospects.

Atlanta badly needed a power hitter, someone who could light a fire under the offense.

“That was such a huge trade for us,’’ Maddux said. “We needed a bat. And we just took off under Fred.’’

Atlanta went onto win 38 of their next 49 games, and was 51-17 after McGriff’s arrival. McGriff hit .310 with 19 homers, 55 RBI and a 1.004 OPS in 69 games. They won the NL West with 104 victories, won the World Series two years later and won the division every year that McGriff was on the team through 1997.

“What was unbelievable was just his consistency,’’ said Maddux, who voted for McGriff as a contemporary era committee member, and is bringing his son to the Hall of Fame induction. “He did it every single year. When you’re good for long periods of time, it means you’re really, really good. He helped us get to the playoffs every year and win a World Series.

“He was just such a good guy. Everybody liked him. I don’t think he had an enemy in the game.

“And that laugh, it didn’t come out too often, but when it did, it made everybody laugh."

The Tampa buddy: Luis Gonzalez

“Oh man, that laugh," Luis Gonzalez said. “He always had that laugh. That Eddie Murphy laugh. When he laughed, you couldn’t help but laugh, too.’’

A five-time All-Star, Gonzalez grew up in Tampa too and was four years younger but attended the same high school, idolizing McGriff.

If you were from Tampa, and hit left-handed, McGriff was the guy every young ballplayer watched.

“I remember we were in the 12-year-old age group, and we would go watch Fred and Dave Magadan," Gonzalez said, “and my parents and grandparents would say, 'You got to go watch these guys. You got to watch them play.' They would come back from the alumni game, and we would get to know them.

“He was always a a great role model to guys like Tino Martinez and myself, always a smile on his face, and he would always spend time with us.

“He always had that helicopter finish with his swing but when he got drafted by Yankees, and went to Toronto, he just became just a total different player. He was just a blue-collar player, not a tabloid headline guy, but when he went to Atlanta and then Chicago and LA, everybody knew who he was.

“He wasn’t our secret anymore."

The first base peers

Mark McGwire

McGwire, sitting in front of his home computer, looks up McGriff’s stats and slowly reads them off, his voice getting louder as each one becomes more impressive.

He stops when he sees that McGriff had at least 586 plate appearances in 14 seasons, wondering if he ever was on the injured list.

He marvels at McGriff’s .377 on-base percentage, never striking out more than 132 times in a season.

“That’s just incredible," McGwire said, “absolutely incredible, with the way he swung, and that power, to have that high of an on-base percentage."

And, then, Big Mac comes to a conclusion:

“He would making $30 million or more today with those stats,’’ McGwire said. “That kind of power, with that kind of consistency, it’s just amazing.

“He’s got one of those smiles, and always seemed so happy, but my, God, what a competitor. And, he could pick it, had a sweet way of picking up the ball, with a very accurate arm. He’s what a Hall of Famer is all about."

David Segui

Slugger David Segui, whose career began four years after McGriff, insists he knows exactly why McGriff was ignored by the voters during his 10 years on the Hall of Fame ballot.

“It was because of his personality,’’ Segui says. “He wasn’t loud. He wasn’t brash. He wasn’t showing anybody up. He wasn’t running his mouth. He wasn’t getting arrested for doing stupid stuff off the field.

“It sounds stupid, but he would have gotten in quicker if he was more of a [jerk]. I’m serious. He was a superstar, but he was such a humble gentleman, treated everybody with respect, and would treat everyone like you were important.

“So, it actually worked against him because of his humility and good nature and was so well-mannered. He’s such a guy nice, he was almost forgotten.’’

Well, except for every one of his peers, particular fellow power-hitting first basemen.

“When you asked who was the first baseman of his era, the most talented, the most feared, he’s on top of the list," Segui said, “but you almost forgot about him because he was such a quiet presence. Everything he did was smooth and graceful, which really matched his personality."

But, oh, Segui will let you in on a secret.

“Never in my life was I ever scared on the field, except for the time Fred was at the plate," Segui said. “I was holding a guy on first, and he hit the hardest ground ball ever hit to me in my life. If it was at my face, I would have been dead.

“It became a thing later on when he was on-deck, I’d say, 'Oh please, God, don’t let this guy get on,' because I didn't want to hold him on with Fred at the plate."

Tony Clark

Now executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, Tony Clark had plenty of heroes growing up as 6-foot-8 first baseman, eventaully hitting 251 career home runs during his 15-year career.

When he arrived in the big leagues in 1995, there was a gold standard for tall power-hitting first basemen.

“I always loved to see other big first basemen do well,’’ Clark said, “but to take it a step further on a personal and professional front, Fred (6-foot-3) was a first baseman that I wanted to try to emulate. There were power guys who were good at first base that were tall, and Freddy was the standard for me.

“I knew if I was going to be a quality big-league first baseman, then I needed to be sound defensively, I needed to hit 30, and I needed to drive in 100. That’s what Freddie did, and he did it every year. So, for me, he was the standard."

And, when Clark is at the induction ceremony this weekend, pardon him if he gets a little giddy.

“There are guys who during the course of my career and afterwards, when I’m around them," Clark said, “I revert back to being younger. Freddie is one of them. He’s one of those guys that I just like being around, and listening to him, because of how I wanted to emulate him.’’

The Hall of Fame classmate: Scott Rolen

Scott Rolen, who’s being inducted with McGriff, doesn’t want to rip the Hall of Fame voting process, or the Baseball Writers Association of America that snubbed McGriff but said that everyone who played in the same era as McGriff had the same thought:

He was a Hall of Fame player, no questions asked.

“I can always go back to [late Hall of Fame second baseman] Joe Morgan when we spoke in Cincinnati," Rolen said. “He always talked about that as a player, you knew who the Hall of Famers were that you played against and with every day.

“So, not any criticism, or the writers, or the process of any kind, but I always believed that Fred McGriff was a Hall of Famer. He was the guy dead in the middle of the order, [493] home runs, had a long career, and was in the middle of so many good teams, and was such a dangerous hitter.

“I always had the feeling that Fred was going to get into the Hall of Fame at some point. I always had a lot of respect for him as a person, and certainly as a player, so I think we’re going to be connected for quite some time. It’s a great honor to be inducted with Fred.’’

HALL OF FAME: A boy was dying. Hall of Fame inductee Scott Rolen quietly became his best friend

The general manager: John Schuerholz

Schuerholz has made thousands of moves in his Hall of Fame career, but the day of July 18, 1993, will live forever.

It was the day that he traded three minor-league prospects, Melvin Nieves, Donnie Elliott and Vince Moore, to San Diego for McGriff.

It was the greatest trade of Schuerholz’s illustrious career.

McGriff became a Hall of Famer while Elliott pitched 35 innings in his major-league career, Nieves hit 63 career homers and Moore never reached the big leagues.

“It was really quiet in our shop, we weren’t talking to a lot of people about it," Schuerholz said, “but we knew we had to get a bomber. We got him, and he became a cornerstone of our offense, and we never looked back.

“Really, he was our type of guy. He played all of the time. He produced. He’s very professional. And he’s such a wonderful gentleman.

“It turned out to be such a wonderful thing for our organization. He was everything we could have wanted. He really is a good human being, a delightful person, and quite the man.’’

The managers

Tony La Russa

La Russa, the Hall of Fame manager who has been battling serious health problems the past two years, recently received clearance from his doctors to attend his first Hall of Fame induction ceremony since 2019.

He wanted so badly to be there this weekend to see McGriff, a Tampa native like La Russa, be inducted along with Rolen, whom he managed for 5 ½ years with the Cardinals.

“I remember [Hall of Fame manager] Earl Weaver telling me that when you watched other players, try to visualize how he fits into your team concept,’’ La Russa said. “Don’t just see how to get him out, but check him out, see what kind of competitor he is, what kind of profile he fits.

“Well, Fred McGriff, from the first day I saw him, always set the right message. He was there trying to beat your ass while understanding what the competition is all about. He always had the presence.

“He always looked the same. There was no extra strut when he was doing well. No head down when he was struggling. He was always on top looking for ways to beat your ass.’’

La Russa said he plans to pop McGriff a question this weekend that has always nagged him:

Why is he called “The Crime Dog?’’

“I was always kind of curious,’’ La Russa said, “and never asked where 'Crime Dog' came from because I love dogs."

La Russa was informed it was a nickname bestowed upon him by famed ESPN broadcaster Chris Berman. Berman called him “Crime Dog" because his last name is similar to “McGruff," the animated dog that helped increase crime awareness and safety. The nickname stuck for the duration of his career.

“Well, I’m just glad he’s in the Hall of Fame, because he certainly deserves it," La Russa said. “Looking back, we all came from the same high school at Thomas Jefferson: Tino [Martinez], Gonzo [Luis Gonzalez], and myself. But as I’m constantly reminded, I’m the only guy who wasn’t a good player."

Buck Showalter

The Yankees, who selected McGriff in the 9th round of the 1981 draft, signed him for $20,000 and traded him just a year later with Dave Collins and Dave Morgan to the Blue Jays for reliever Dale Murray and Tom Dodd.

McGriff had played just 91 games in rookie ball, hitting nine home runs, but the Yankees felt they were deep in first base prospects. They had Steve Balboni. They had Marshall Brandt. They had Orestes Destrade. They had a fella named Don Mattingly, a converted left fielder. And they had a Class AA first baseman by the name of Buck Showalter.

Balboni became a World Series champion with the Kansas City Royals.

Mattingly became an MVP with the Yankees.

Showalter became a four-time Manager of the Year winner.

McGriff became a Hall of Famer.

“Holy [expletive], can you believe we had all three of them?’’ said Showalter, now manager of the Mets. “Fred was skinny, athletic, smiled easily, and didn’t take himself too seriously. He just embraced the uniqueness of his swing. He was kind of into the launch angle long before people were, and no one tried to overcoach his swing.

“I love the guy. Everything was about the team. He had great style because he didn’t have any. His substance was his style. It was a never look-at-me mentality. He’s everything you want in a ballplayer.’’

Follow Nightengale on Twitter: @Bnightengale

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Hall of Fame gets Fred McGriff: 'Crime Dog' beloved around baseball