Erik van Rooyen, friends and family live in honor of 'Trazzy'

Erik van Rooyen was in the gym when his phone chimed.

It was Nov. 1, 2023, the end of the worst year of his professional career, and a day he will never forget. Heading into the last three weeks of the PGA Tour season, the then-33-year-old South African was the FedExCup bubble boy. With no margin for error, the goal was to fight like hell, get through the remainder of the fall and reset for next year. The prospect of losing his card, to piecemealing a schedule together on three different tours, was hard to accept when, not long ago, van Rooyen was a top-50 player in the world. And besides, over the past few months, he believed he was making real progress. Rebuilding his battered body. Fine-tuning his swing with a new coach. Regaining his lost confidence. Now, he just needed more time.

Tournament week at the World Wide Technology Championship had already begun inauspiciously. The week prior, van Rooyen was so sick he could barely get out of bed. Upon arrival in Cabo, his swing felt just as shaky; he was hitting wild hooks with even his most lofted clubs. Desperate to find some key that worked, he relied on over-the-top fade swings that still, somehow, produced a slight draw. Whatever, he sighed. This’ll have to do.

The Wednesday pro-am offered one final chance to get right before the start of the event. It was 90 minutes before his tee time when he tapped into his phone to read the latest message in the group chat with his former teammates.

“Boys,” the text started.

“Just met with my doctor again.

“It’s not good news.”

And for the first time all season – maybe for the first time in his life – van Rooyen’s golf no longer mattered.

"Tell your best friend you love him."

While Erik van Rooyen ( @FredVR_ ) fought for his TOUR career, his best friend Jon Trasamar was fighting for his life.

This week at the PGA Championship, he’s playing "For Trazzy." @RyanLavnerGC pic.twitter.com/0zzp6BCfAw— Golf Channel (@GolfChannel) May 13, 2024

* * *

THE FIRST PERSON WHO greeted van Rooyen following his 20-hour journey from South Africa was Jon Trasamar.

In September 2009, Trasamar traveled 2 ½ hours from his family’s home in Blue Earth, Minnesota, just to welcome van Rooyen to the U.S. and, soon, to the University of Minnesota golf team, where they were about to be teammates. Before long, they were inseparable, freshmen roommates who became best friends, their bond strengthened not just by their close proximity but the shared hardships of playing elite Division I golf together. They were small-town kids with outsized dreams. Van Rooyen was the team’s top player, never winning but finishing runner-up in the Big Ten Championship his senior year. Meanwhile, Trasamar, nicknamed “Trazzy,” served as the team leader and captain, setting the tone with his work ethic, analytical approach and inclusive attitude.

“He was the model,” says Alex Gaugert, a four-year teammate.

A few players on the team were equipped for the next level, and van Rooyen returned home after graduation to chase a card. He joined the Sunshine Tour, steadily climbed through the European tour ranks and, after a strong 2019 season, crashed the top 50 in the Official World Golf Ranking (once reaching as high as No. 40) to create an entry point into PGA Tour events.

Secure on the course and stable off it, van Rooyen was the picture of contentment: He had hired Gaugert, his old teammate, on the bag full-time and married Rose, his college sweetheart, with Trasamar serving as the best man in the wedding.

“It was always the dream that we were going to play the PGA Tour together,” van Rooyen says. “That is literally the ultimate for me, playing with your best mate.”

But by spring 2022, Trasamar had reached a career crossroads, torn over whether to continue to play professionally without a clear end game. He had found love, too, getting set up through mutual friends with a Midwest girl named Allie Haen, whose uncle is longtime PGA Tour player Jerry Kelly. It was an ideal partnership, for Allie knew intimately the trials and tribulations of a persistent pro, and she wholeheartedly supported Trasamar as he took caddie gigs and signed up for Q-School and played more than a half-dozen mini-tours, trying to make his mark.

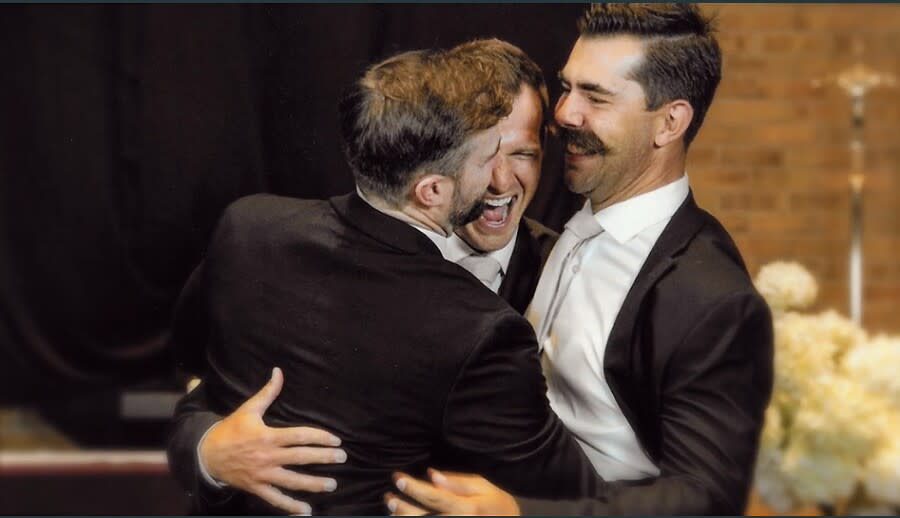

They got married in Madison, Wisconsin, at the spot where they first met, on a spring day marked by morning snow and then beautiful sunshine. Trasamar and van Rooyen posed for pictures in matching dark-gray suits with crisp white shirts and gray ties, young men who, after all these years, had become bigger cheerleaders than competitors.

“They were almost like brothers – that’s how close they were,” Allie says. “They wanted to play professionally at the highest level they could, but beyond that, as men, they wanted to be the best versions of themselves. They wanted to start families. They wanted to live a life that they were proud of.”

But just two months later, that ideal took on an entirely different meaning.

* * *

IT WAS ALLIE WHO first suggested that her husband go see his dermatologist. There were two moles – one on Jon’s back, another on his knee – that she thought looked concerning. Her suspicions were confirmed a month later, when the doctor called: Those spots had tested positive for melanoma.

The early prognosis, at least, was optimistic. Oncologists removed areas around the moles to ensure that the margins were clear. “They were encouraged by what they were initially seeing,” Allie says. A full-body scan showed that Jon was once again disease-free.

After the scare, he felt more compelled than ever to pursue his pro goals. “He felt like he was given a new lease on life,” Allie says. “That this was a second chance.”

One of the first people Trasamar told about his diagnosis was van Rooyen. He shared the news over beers at one of their old haunts near campus.

“You don’t really think much of it,” van Rooyen says. “The doctor said, ‘You’re going to be fine.’ We’d check up every other week, and now things are going great. I was 32. He was 32. You feel invincible. You don’t think anything’s going to happen.”

And besides, van Rooyen was now dealing with his own health concerns. Less than a year after his breakthrough win at the 2021 Barracuda Championship, his ascendant career had been slowed by lower back and neck issues. Preparing for the 2022 Open, van Rooyen hurt his neck at St. Andrews and, by the eve of the tournament, couldn’t even chip. He withdrew and headed to South Africa for three months of rehab. When he finally returned to competition, he was a shell of his former self, racking up missed cuts, tanking in the rankings and, before long, imperiling his Tour status.

“Very frustrating,” van Rooyen says. “I had played my best golf, and then you get injured and you’re so desperate to get back to that place. It’s hard.”

At the same time, Trasamar began suffering setbacks, too. At his three-month post-procedure appointment, doctors found an inflamed lymph node in his back that needed to be biopsied. It was positive for melanoma. That led to another scan that showed an additional spot on his rib. Also melanoma. Over the course of a few months, he vacillated from having superficial moles to no signs of cancer to scans revealing two new spots and immunotherapy treatment.

“As a melanoma patient, there’s always a chance for recurrence, and I think that’s your biggest fear,” Allie says. “Even if you’re feeling good and you have encouraging scans and test results, you always wonder in the back of your mind what the next scans are going to show. You’re always flipflopping between being really excited and happy and encouraged, to being really disappointed and discouraged and heartbroken. And I think that’s really tough to manage and try to wrap your head around.”

Soon, there was even more instability. In early 2023, Trasamar discovered blood in his urine and flew back to Minnesota to see his oncologist. It was there that he learned that the cancer hadn’t just returned – it had spread throughout his body, into his liver, spine, back and legs.

One of the biggest areas of disease burden was his femurs, and emergency surgery was scheduled to stabilize the legs of his 6-foot-2-inch frame with a titanium rod. There during his post-operation recovery was van Rooyen, who broke away from the unending grind of his Tour schedule to be by his brother’s side. For months, he jetted to Rochester to listen to him, to encourage him, sometimes just to sit in the waiting room with him.

“He just wanted to be there for Jon,” Allie says, “and he wanted Jon to know that he wasn’t alone. Erik was an incredible source of strength for him – always asking what he could do for Jon and how he could help him, and give him courage to tackle whatever was being thrown at him.”

After a new round of treatment that spring, Trasamar had another follow-up appointment to chart his progress. And this time, the news was astonishing: His skin was completely clean. There was no evidence of cancer anywhere.

“We felt like the luckiest people in the world,” Allie says. “We thought the worst was behind us. We had gotten through this.”

“We’re crying on the phone and so happy,” van Rooyen says. “He’s going to pull through.”

Van Rooyen saw Trasamar again that summer, ahead of the 3M Open in Minnesota. Trasamar appeared and sounded normal. He was walking. Talking optimistically. He’d lost a bit of weight but nothing drastic. He’d even signed up for the Monday qualifier on Tour but withdrew beforehand because of back tightness.

“The whole time, I’m under the impression that, yeah, he’s grinding,” van Rooyen says, “but he’s going to make it.”

Comforted by his best friend being on the mend, van Rooyen tended to the small matter of resurrecting his own career. After a miserable summer stretch in which he missed nine cuts in a 10-tournament span, he failed to qualify for the FedExCup playoffs and headed to Europe to find some form. He was already beginning to strike the ball better after switching to swing coach Sean Foley that summer, and the results soon followed. Heading into the World Wide Technology Championship, the third-to-last event of the Tour’s fall series, van Rooyen was sitting precariously on the card cutoff – No. 125 – and needing one more solid finish to secure his status for next year.

“Being on that bubble,” van Rooyen says, “it’s a hard place to be. The pressure just keeps building and building. I don’t want to lose my card to the PGA Tour. I don’t know where that would have left me.”

Then came Mexico.

The illness.

The wild hooks.

And the text in the gym that changed everything.

* * *

TRAZZY HAD JUST SENT a message.

He had undergone an MRI a day earlier, and the findings were devastating.

The tumors had eluded every possible line of defense.

His doctors were out of treatment options.

There was nothing else that could be done.

“I don’t have a lot of time left,” Trasamar wrote, “sounds like 6-10 weeks.”

There in the gym, van Rooyen broke down.

It didn’t make sense. Van Rooyen had just talked to him a week earlier, when Trasamar reported some tightness in his calves and hamstrings, but he was using his walker and working on his gait and feeling optimistic.

And now this?

Tumors pushing on his spine? Every option exhausted?

“A huge surprise,” van Rooyen says. “It was just out of the blue. I think that was the hardest part.”

He read and re-read the 135-word text, then wiped away tears and soldiered through his pro-am round. Gaugert called his wife and parents. “I don’t know how he’s going to play through this,” he said.

Afterward, Gaugert huddled with his boss and came up with a rallying cry for the rest of the week: Do It for Trazzy. Van Rooyen scribbled his initials on his golf balls, with little musical notes as a nod to his and Trasamar’s shared love of the guitar and piano.

“I think that was pretty powerful in a selfish way,” van Rooyen says. “It certainly helped me focus with no fear whatsoever, no regard for the result. In a sense, that gave me a lot of freedom to play some of my best golf, knowing that I’m doing something for more than just myself.”

The five hours between the ropes were a blur. Head down, heart hurting, stomach churning. Scores of 68-64-66. Solo third, a shot back, with 18 holes to play.

“I still don’t know how we did it,” he says. “After golf, I’d be in my room bawling my eyes out, and then on the morning-of, it’s like, OK, let’s go do the job. We’re doing this for Trazzy, so we can go see him.”

Relying on his friend’s strength to bolster his own, he’d look to Gaugert before every shot in the final round: “This one’s for Trazzy.”

And it worked.

Lost for years, van Rooyen finally rediscovered his swing. He made birdie on 10. Then another. Then another. Then another. He was climbing the board, the leaders in sight, momentum building. Then on 15, the break of the tournament: He tugged his approach left, his ball appearing destined for the penalty area. With his shot mid-flight, he even turned away, unable to watch his own demise. But his ball found dry land and – somehow – clung to a tuft of grass above the red hazard line. From there, he rushed up to play and got up-and-down to save an unlikely par.

“The dude was looking over us,” Gaugert says.

Actually, Trasamar was watching the unthinkable unfold from the Mayo Clinic some 3,000 miles away, where he’d been admitted to manage his pain before being discharged to hospice. Trasamar’s college friends crowded around his bed as he cued up the coverage on his phone, his best friend playing the most inspired golf of his life.

“I don’t think anyone could really believe what was going on,” Allie says. “It felt like a moment of divine intervention.”

Through a torrent of tears, they watched a storybook finish: back-to-back 20-footers for birdie on 16 and 17, then the clincher – a 20-footer for eagle that gave van Rooyen a back-nine 28 and a one-stroke victory.

On that 18th green, so much was rushing through van Rooyen’s mind – his performance, his pain, his purpose. The satisfaction of saving his own career. The sorrow of knowing the end was near.

“I didn’t feel anything,” he says. “When you win a tournament, it’s one of the greatest feelings ever. You work so hard to get to that point. You’re playing against the best players on the planet. The margins are so slim. To win is not easy. But at that point, I was so numb. Just absolutely numb.”

That feeling continued deep into the night, when van Rooyen and Gaugert drank tequila and toasted to Trazzy. His status secure and his schedule now open, van Rooyen could have continued chasing points in the remaining two Tour events that would have set up his early 2024 even better. But by the time he finally dozed off at 3 a.m., he’d already thought better of it.

“We were tired. We were done,” he says. “We just wanted to go see a friend.”

Later that morning they boarded a flight to Minnesota, to say goodbye.

* * *

THERE WAS LITTLE TALK on the plane, because, really, what else was there to say? Van Rooyen and Gaugert were both in disbelief. They’d kept their card. Banked $1.4 million. Earned a two-year exemption. And now, hours later, they were traveling to see their dying friend one last time.

“The two things just don’t compute,” van Rooyen says.

He didn’t know what to expect the following day at the hospital, but in hindsight, he probably should have known; Trasamar had stopped answering his FaceTime calls a month earlier. Seeing him now, how the cancer and treatment had ravaged him – his weight, his hair, his voice – was almost too much to bear.

“I wouldn’t have recognized him if he was walking past me on the sidewalk,” van Rooyen says. “So I was just praying. Praying for relief. Praying for it to be done and go away.”

The hospital room was a revolving door of friends and family, all of them at least heartened, momentarily, by Sunday’s magical moment in Mexico for Trazzy. Flanking Trasamar’s bed, van Rooyen and Gaugert shared laughs from college, the tournaments they played, the fun they had, the trips they took, their team captain drifting in and out of the conversation, his wife there to fill in any gaps.

“I don’t think Erik probably realized how important of a week it was for Jon in the sense that this tournament gave him something to be excited about, gave him a sense of joy that otherwise probably wouldn’t have been present,” Allie says. “I’m so grateful to Erik for providing those moments. Jon knew how much it meant to him, and he couldn’t have been prouder or happier for Erik than he was that week.”

After an hour, van Rooyen turned to leave.

“I grabbed his hand,” he says, “and the last thing he told me was, ‘I’ll see you soon.’”

* * *

IT’S MASTERS THURSDAY, FIVE months to the day since Jon Trasamar passed away.

That was Nov. 11, or 11/11 – a numerical sequencing that was lost on no one who loved him.

“It’s an angel number, and it represents guardian angels,” Allie says, “and I think it perfectly depicts who he was.”

This morning, she’s sitting in the living room of her relatives’ home in Scottsdale, Arizona. In a gray jacket with brown hair worn down in waves, she’s reflecting on these two unimaginable years – the shock diagnosis, the unusual cancer journey, the cruel end – with stunning clarity. How it’s taught her about life’s fragility and the importance of being surrounded by those she loves. How it’s forced her to be positive, brave, strong. Just like Jon.

“I keep seeing this quote that says, ‘Keep going, because the person in heaven doesn’t want you to quit,’” Allie says. “And every single time I see that, I think of Jon. He never quit, and that gives me the strength to continue to be strong, to face whatever is forthcoming from a place of courage. Because if he can go through all of that and maintain that positivity and that strength, then I can do that, too. I rely on him now for that strength to move forward.”

There’s a photo album on the table and the first round of the Masters on a nearby TV. There’s her late husband’s best friend, with his bushy mustache and affable demeanor and picture-perfect swing, pouring in another birdie. Van Rooyen is now atop the early leaderboard at Augusta, a continuation of the best first quarter of a season in his career. Later, he’ll tell the media that, these days, he isn’t short on motivation or inspiration.

“I think Erik will carry Jon with him always,” Allie says as she watches the coverage. “I think Jon was a good source of confidence and strength for him to remind him that you can do hard things. That you’re stronger than you realize. It’s not until you’re put in a situation where you have no other choice but to be strong that you realize how strong you truly are. And I hope Erik feeds off that.”

That spirit has manifested itself in different ways, and at different times, during van Rooyen’s bounce-back season. Sometimes, it’s on a tee shot when he tells himself, This one’s for you. Others, it’s a text from his college group chat as they try to organize another golf trip, this time without their leader. At home, it’s a glance at the wedding photo in his bedroom.

“It still doesn’t make sense, and it still sucks,” van Rooyen says. “I don’t think anything is ever going to fill that void. I think you just learn how to live with it.”

The painful, powerful memory lives on his right wrist, in a homemade, maroon-and-gold bracelet that reads, “BE LIKE TRAZZY.”

It’s a reminder to play fearlessly.

To prioritize his friends and family.

To live well and love hard.

“You won’t know when your time comes, and I would certainly rather look back thinking that I went all-out – that there was no doubt, there was no fear,” he says. “His life and his passing certainly pushes me to be the best version of myself.”