Dan Campbell did nothing wrong

Dan Campbell danced with the one who brung him. That his dancing partner tripped and fell on their face and shattered their orbital bone is another story entirely.

The muscle-bound, overly-caffeinated, swashbuckling Detroit Lions head coach, hyper aggressive on fourth downs throughout his head coaching tenure, continued his unorthodox points-maximizing ways into the most important game in Lions’ history: A road affair in the NFC Championship Game against a heavily-favored 49ers team sporting the league's second highest point differential in 2023.

Campbell during the regular season outpaced all coaches in fourth down aggressiveness, going for it on 34 percent of Detroit’s fourth down conversion opportunities. That, in fact, made the 2023 Lions the most aggressive fourth down team of the 21st Century, according to ESPN Stats & Information Research.

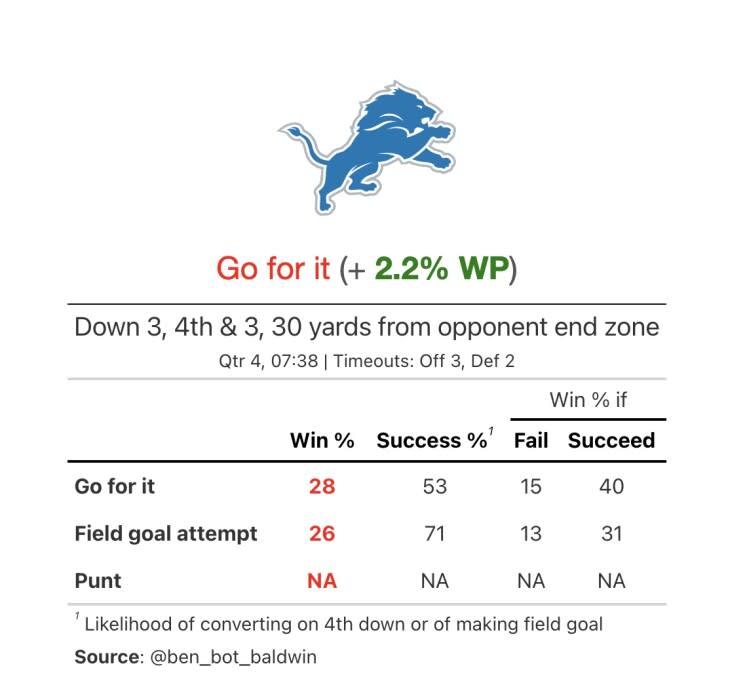

It tracks that Campbell went for it on two second-half fourth downs in Detroit’s title game loss to San Francisco. The Lions failed on both conversion attempts, one of them a fourth and two from the Niners’ 28-yard line early in the third quarter, the other a fourth and three from the 49ers’ 30-yard line with roughly 10 minutes to go in the game.

From the cold, bloodless perspective of the numbers, Campbell’s fourth down decision making was sound, per Ben Baldwin’s Fourth Down Decision Calculator, which accounts for all manner of factors and offers a calculation on what a team would gain (or lose) by converting on fourth down.

ESPN Analytics was in agreement: Going for it on the third quarter fourth down attempt would have bumped Detroit’s odds of winning the game from 90.3 percent to 90.5 percent. The fourth quarter attempt would have nudged their win probability from 38.8 percent to 39.1 percent (the tiny discrepancy makes one wonder why the anti-analytics crowd is warring online with the analytics nerds).

These fourth down attempts, as you surely know by now, did not work out the way Campbell had hoped. Detroit’s shoddy defense, bending and breaking at an alarming pace, couldn’t fend off Kyle Shanahan’s EPA Machine and the Lions blew a 24-7 halftime advantage to lose, 34-31, in what will be remembered as an all-time meltdown.

Ever the process-oriented coach, Campbell — fighting off the raw emotion of such a crushing defeat — said in his postgame presser that he did not regret trying to win the game and send his underdog Lions to play the Chiefs in the Super Bowl.

"It's easy hindsight. I get it,” Campbell said in what could have been a direct response to those who judge football decision making purely on what transpired. “I get that, but I don't regret those decisions, and it's hard. … It's hard because we didn't come through, and it wasn't able to work out, but I don't. And I understand the scrutiny I'll get — that's part of the gig — but it just didn't work out."

This NFC title game was a watershed moment in football analytics. A head coach doing anything and everything to maximize his team's win probability is a glorious victory for the so-called analytics movement, even if it's widely interpreted as an utter failure because the Lions did not win. Process over results. So it goes.

Rejecting the Brandon Staley Path

Campbell, unlike so many NFL head coaches, never tries not to lose. Through three seasons at the helm of the Lions, Campbell has refused to lose in a traditional way despite constant calls from the media and NFL fans for him to give up his fourth down capers. They have pleaded with the hulking head coach: Do the right thing and punt on fourth and short at the 50-yard line. Take the points on fourth and goal from the 4-yard line. Cede to generations of ultra-conservative fourth down decision making. Be an adult, Dan, and stop trying to score points. Campbell has heard this for three years and said no, absolutely not.

Campbell has not gone down the path of Brandon Staley, who was stung by a few process-oriented fourth down decisions gone awry during his first year as Chargers head coach and promptly turtled, becoming one of the league’s most conservative coaches. Staley, like so many coaches before him, saw the perils of losing in an untraditional way. The heat both from inside and outside the organization gave Staley every incentive to forgo aggressive fourth down calls. He then spent two forgettable seasons failing traditionally. For his efforts, Staley will likely never be an NFL head coach again.

Lions players have fully backed Campbell’s pushback against NFL fourth down groupthink. That includes Jared Goff, who, like his coach, had no regrets about trying to convert second-half fourth downs as underdogs facing a high-powered offense that showed no signs of stopping in the final two quarters.

"I love it. Keep us out there. We should convert," Goff told reporters after the game, adding that “you can change a game if you convert” fourth downs.

They didn’t, but they could have. That’s the entire point of bucking fourth down wisdom passed down through generations of coaches who desperately did not want to fail untraditionally and lose their jobs. It’s an approach that has total buy-in from Lions players, if not armchair analysts who have spent their entire football-watching lives seeing coaches — good, bad, and legendary — capitulate on fourth and short.

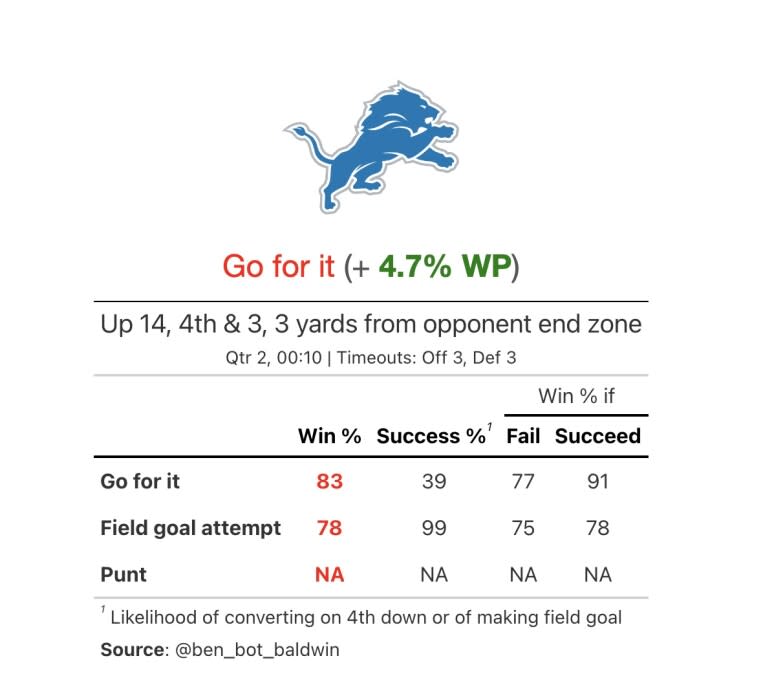

You may be aghast at the suggestion that maybe, just maybe, the Lions were not aggressive enough against the Niners. Campbell trotted out the field goal team with 10 seconds remaining in the second quarter with a chance to go up 28-7 — an outcome that would have increased Detroit’s win probability by nearly 5 percent. It was a dagger-in-the-heart moment that never was.

Those most fiercely critical of Campbell have, as usual, used the concept of momentum as a weapon in the fourth down discourse. Momentum serves as a useful weapon precisely because it is undefinable; one cannot disprove momentum, no matter how hard one might try. Maybe momentum is found in the collective unconscious, a sort of shared understanding of the psychological state of warrior-athletes as they battle in the colosseum. Whatever it is, momentum is always used as a cudgel against those who rely on definable measurements designed to inform optimal decision making. Momentum is used as a counter to the argument that a game can be understood, or that a competitor can maximize their chances to win based on oceans of data. Momentum truthers say no: Winning is in the gut.

That a game’s momentum swings after a team has made strategic, often analytically-based adjustments to their opponents’ game plan seems not to factor in how analysts and fans view momentum: As the antidote for overwrought analytical thinking.

George Kittle, after the 49ers made the necessary second half adjustments against the Lions and completed an improbable comeback, called analytics enthusiasts' denial of momentum the “biggest load of horse crap that I’ve heard in my life.”

As proof of momentum’s existence, Kittle cited the increasing volume of Niners fans once the team had stymied the Detroit offense and finally moved the ball against a Lions defense that features one of the worst coverage units in the NFL. The question follows: Should Dan Campbell have made more conservative fourth down calls in the second half in order to stem the tide of the 49ers' momentum? Should he have simply hoped that three pointers would win the day against a 49ers offense that had bludgeoned the Lions defense after halftime?

What, I would ask Mr. Kittle, is the antidote for momentum? Perhaps none exists. Such is the power of momentum.

Campbell wants to win. For that he is going to be besieged with criticism from results-based analysts and talking heads — folks who will cite the successes of conservative coaches from bygone eras, folks who care not for win probability or expected points or anything that might be found on a spreadsheet, but only for what happened, for the final outcome. The process to arrive at a decision, for those who side with the mystical concept of momentum over the hard math of analytics, does not matter at all.

A Jahmyr Gibbs fumble, a long Brandon Aiyuk reception on one of Brock Purdy's many would-be postseason interceptions, a critical Josh Reynolds drop: These things happen. But these things are results, and have no relation to the process from which they derived.

Dan Campbell, in other words, did nothing wrong.