How Climbers Can Periodize Their Training to Hit Peak Form

This article originally appeared on Climbing

The following was excerpted from the newly released “The Science of Climbing Training: An evidence-based guide to improving your climbing performance” by Sergio Consuegra. Learn more about the book here.—Ed.

How was Usain Bolt able to hit peak physical, technical, and mental form at 9.35 p.m. on 16 August 2009 at the World Athletics Championships in Berlin, when he ran the 100 meters in 9.58 seconds? Art? Science? Luck? Experience?

The planning of sports training is 10 per cent science and 90 per cent art—but don't turn your nose up at this 10 per cent! Compared to training with no plan at all, a well-designed training plan can improve performance by 1.5 to 2.3 per cent (Munoz, 2017). Although it might seem trivial, you'll soon see the difference that this can make. A proper training plan also shows greater awareness of the biodynamic changes in your body, as governed by the principles of training, which translates into a lower chance of injury and, above all, a much greater respect for you and your body.

Basic Concepts: Macrocycle, Mesocycle, and Microcycle

Before starting to cook (planning), you need to know what ingredients to use (skills to develop) and what utensils (units of planning) you're going to need.

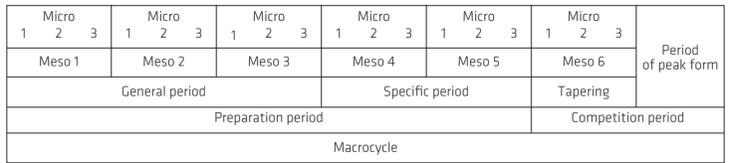

Macrocycle: the basic unit of planning. A macrocycle is defined as an extended period of training resulting in a higher level of performance (adapted from Sole, 2006). A macrocycle is divided into various mesocycles. It's important to stress that in order to improve performance, it's essential that the body can establish a state of homeostasis.

Mesocycle: a medium-length block of training designed to achieve intermediate goals as part of the wider training process (Sole, 2006). A mesocycle is divided into various microcycles.

Microcycle: a short block of training designed to work on individual skills or qualities.

Defining these three units as long, medium, and short blocks of time avoids labelling the macrocycle as a year, the mesocycle as a month or a quarter, and the microcycle as a week. They may, or may not, coincide. You could have several macrocycles in a season, or just one. It all depends on which periodization model you're using.

There are many periodization models (linear, non-linear, block, integrated, and so on), each with their own advantages and disadvantages. The suitability of any given model depends on the sport, the athlete and their level of experience. This book will focus on two linear models (the most simple to understand and put into practice) and one block (ATR) model that allows for multiple points of peak form in a season, which, in my experience, is highly applicable and effective for climbing.

As these models are designed for use in (practically) any sport, they refer to periods of training for competitions. However, this doesn't mean they're only designed for competition climbers: simply take competition to mean any challenge, test, checkpoint or project.

Linear Periodization

The classic periodization model, referred to as traditional or linear periodization, was developed by Matveyev (1977). It uses the season as the basic unit of planning (the macrocycle). The end of the macro-cycle and the point of peak form coincide with the final or most important competition of the season, although it is possible to have two points of peak form in the same macrocycle.

Matveyev divides the macrocycle into three periods:

Base or preparation period: the aim of this period is to build up basic fitness and movement. It is further divided into:

1. General preparation period: multilateral training (non-specific, varied, multicomponent) takes precedence over specific training (training specifically for climbing). The focus is on volume rather than intensity, creating a solid foundation for the training load in the specific preparation period. It's commonly referred to as the 'preseason'. The mesocycles in this period develop adaptation to strength, endurance, and hypertrophy training, through general and non-specific exercises. In training for climbing, this phase should be equally non-specific. We should aim to introduce different types of movement, correct basic technique, and amass a broad range of climbing experience (different disciplines, rock types, styles—slabs, cracks, overhangs, dihedrals, and so on), in addition to building continuity and endurance. The general preparation period could account for as little as 20 to 30 per cent of the base period for advanced climbers or as much as 60 to 70 per cent for less advanced climbers.

2. Specific preparation period: specific training takes precedence over multilateral training. There's a notable increase in intensity and a slight reduction in volume. The mesocycles in this phase cover maximum strength, power, and RFD. The climbing becomes more specific, applying and developing the skills introduced in the general period in order to maximize performance. The focus shifts to climbing on routes/boulder problems and rock types that are more specific to our end goal for the season.

Competition period: in this period, which is also known as tapering, there's a significant drop in volume and the aim is to reach peak form for the final competition or end goal of the season. There's also a significant drop in specific physical conditioning (we should have already reached maximum potential in the specific preparation period and the goal now is to maintain it). Finally, the focus shifts to specific wall-based training, on either rock or plastic. We should be working at maximum intensity (no higher than in the specific preparation period) on routes where we can perfect the style, grade, and skills (strength, continuity, endurance) of our end goal. According to Mujika and Bosquet (2016), tapering is beneficial at any level of ability whenever the training load needs to be reduced.

Any training load will cause some level of fatigue which, logically, will limit our level of performance (the more tired we are, the worse we perform). However, any training load will also raise our physical fitness and, as a result, will improve our level of performance. The success of tapering lies in finding the right balance between our level of fatigue (on a macrocycle level) and our level of physical fitness.

The average improvement in performance observed in quality research is 1.96 per cent. This might seem negligible or even laughable, but according to Mujika and Bosquet (2016):

In a swimming event at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games, the difference between first and fourth place was 1.62 per cent, while the difference between third and eighth place was 2.02 per cent.

In the 1,500 meter at the Athens 2004 Olympic Games, the difference between first and second place was 0.012 seconds (0.05 per cent) and the difference between first and third place was 0.05 seconds (0.23 per cent). As you can see, at an elite level, margins that might seem trivial are the difference between one medal or another. In climbing, although there are no similar studies, these small margins could make all the difference when it comes to sticking a hard move or using a crucial handhold.

Mujika and Bosquet (2016) give the following guidelines for tapering:

The volume of training should be reduced by 60 to 41 per cent over the four weeks prior to the competition.

First reduce the number of training sessions, then reduce the duration of the sessions.

The intensity should remain constant, not increase.

The last few sessions shouldn't be used as a test.

Calorie intake should be adapted to the new energy needs in order to avoid weight gain.

Priority should be given to movement efficiency and the development of maximum power.

For best results, favor heavy weights over light weights.

It's essential to ensure full recovery.

When done correctly, tapering increases the diameter of fast-twitch muscle fibers, boosts neural electrical activity, and makes glycolysis more efficient at maximum intensity, in addition to modifying anabolic hormonal response.

Mujika and Bosquet refer to a quote from the world of competitive swimming, which we could all bear in mind when tapering or approaching our end goal(s): 'You don't need to feel good to swim fast.' Feelings are fundamental, especially when we're facing a win-or-lose situation after months and months of training. However, if we've trained properly and our body has adapted to the training load and is in a state of homeostasis, we're much more likely to top our target route, even if we start doubting our chances of success.

Transition period: this is when we start losing form and begin the process of recovery and regeneration.

This model of planning is known as linear periodization as there is a linear or proportional increase in intensity and a linear or proportional decrease in volume over the course of the macrocycle.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of Matveyev's linear periodization model?

Main advantages of linear periodization:

It lays strong foundations in each skill or quality as they are trained over a long period of time.

The risk of injury is fairly low as it's a progressive system.

It's a safe model for beginners.

Main disadvantages of linear periodization:

It takes a long time to reach peak form.

There's no scope for readjustment until the first period of peak form.

It's not recommended for advanced athletes as the skills aren't revisited during the year. It's fallen into disuse in many sports as it's less applicable to performance.

To learn about the other types of periodization training available to climbers (and much more) you can purchase “The Science of Climbing Training” here.

Also read:

New Book 'More' is an Unflinching Look into Climbing and Motherhood

The Wide Boyz' Epic Quest to Send One of the World's Toughest Cracks

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.