Butch Reynolds still seeks vindication years after being accused of doping

Butch Reynolds’ story, which includes a precipitous rise and a faster fall, possesses enough drama to craft a film.

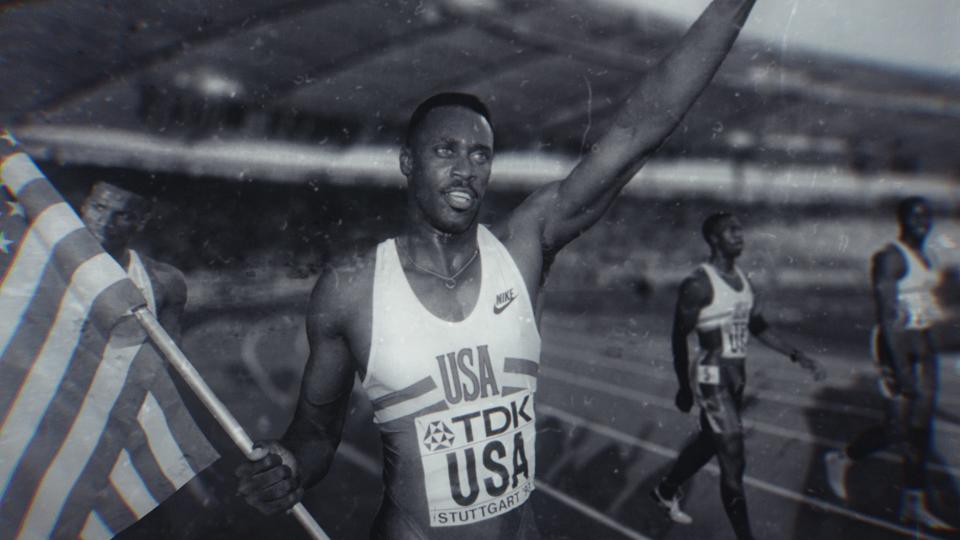

Now, the Akron native and track superstar — who in 1988 set a world record in the 400 meters that stood for more than 11 years — is in search of complete exoneration.

That's the one thing he hasn’t had in his battle to clear his name of doping accusations that derailed his career and thrust him into a legal morass.

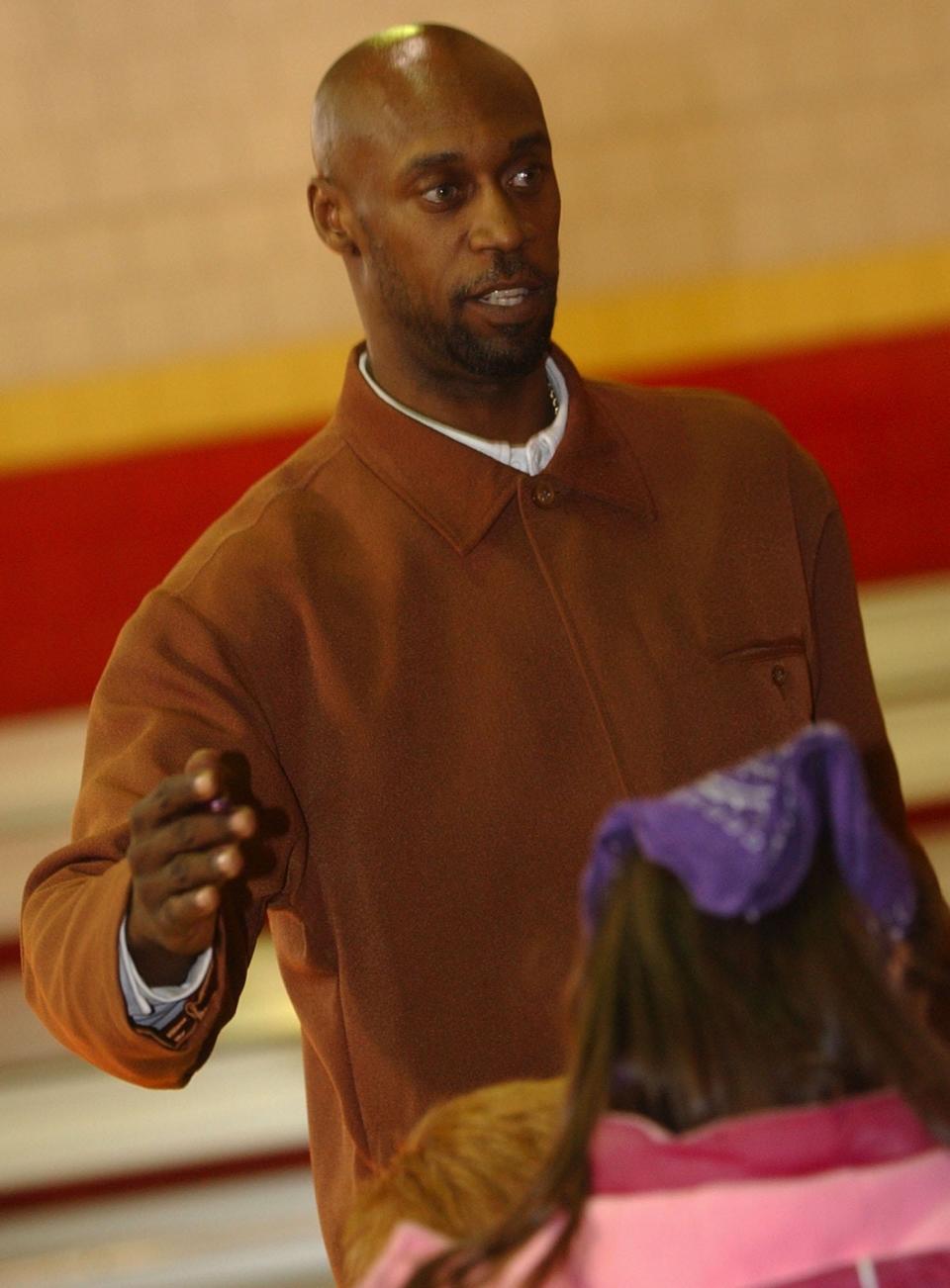

Reynolds, who will celebrate his 60th birthday in June, was LeBron James before LeBron James, imbued with a sense of civic pride and moral obligation to give back to Akron.

More: How many of these famous people from Akron do you recognize?

No one will ever have complete insight into another individual, but Ed Novak, a track teammate of Reynolds at Archbishop Hoban, where Reynolds’ records still stand, described the former track standout as someone with "confident humility." It was a trait that rubbed off on the entire team, even though Reynolds was setting records in the long jump and his signature event, the 400.

“He exhibited a confident humility,” Novak said during a recent phone conversation. “I don't think you would know what a superstar he was. I mean, he just related to people in a very friendly and sincere and kind way.”

That is why when accusations were made about the world class athlete with whom he once shared most valuable player recognition, Novak was shocked.

Novak still sounds shocked that it ever happened. A practicing mental health professional in Akron, he said he’s never believed the allegations against Reynolds.

Butch Reynolds tripped up by anti-doping rules

It’s not difficult to take that position given Reynolds’ story. After winning a gold and a silver medal in the 1988 Seoul Olympics not long after setting the 400 world record (43.29 seconds), his life was tripped up by a positive test for performance-enhancing drugs in August 1990. Despite winning in court — including a $27.3 million judgment (that he was never able to collect) against the International Amateur Athletic Federation, the sport’s governing body at the time — and in the United States Supreme Court, he’s never felt complete vindication.

Perhaps that’s why Reynolds, with the help of Buchtel High School graduate and director Ismail Al-Amin, is willing to face the ghosts of his past.

They loom, and perhaps through confrontation via the documentary “False Positive” is the only way to vanquish them.

“I've been fighting ever since that day, and the only reason why I let it go for 20 years, I got remarried and I wanted to focus on my family. I love being a dad, man. Being a dad — capital D-A-D — is something that in my time in my life, it was bigger than a gold medal,” Reynolds said while sitting in the lobby at a downtown Cleveland hotel hours before the film premiered at the Cleveland International Film Festival.

More: Cleveland International Film Festival gets a taste of Akron with four movies

“It was bigger than making a hundred million dollars, bigger than 27 million to me is being called a dad by my two kids. And some people sitting out there probably say he's crazy. ‘Give me my 27 million.’ And I respect that.”

Reynolds is a ball of energy even while sitting down. As he discusses what happened to him and his career — allegations that arguably cost him millions in endorsements — his toes keep their own consistent rhythm in time with the emotion in his voice. It rises ever so slightly when he talks about clearing his name by exerting a measure of pressure on the IAAF, now known as World Athletics.

“Don't get me wrong, because see, they got to understand though that money wasn't the issue and it's still not the issue right now,” he said. “What's more the issue is the message.”

Butch Reynolds’ message to world is clear

The mission is to clear his name — just as he promised his grandfather. The message is what attracted Al-Amin. The duo worked together on youth initiatives in Akron and the director and Kent State University professor was drawn to Reynolds’ story.

Al-Amin is blunt. Like many of Reynolds’ contemporaries, he could not say he always thought Reynolds was clean. He points to that era in track when several athletes were caught doping.

“We talking in 1988, we talking [about] Ben Johnson scandal, I think pretty much the public pretty much agreed that track and field was a dirty sport at that time,” he said.

Getting to know Reynolds was the key to understanding who he was as a person, and subsequent research, including scouring court documents, led him to the same conclusions U.S. courts had made. What Al-Amin didn’t understand, he said, is why the story had not been dealt with in almost 20 years.

“I think there was a lot of ambiguity around it,” he said. "There was a lot of unanswered questions around it, around the facts of the case. … I was just looking to tell a very objective, truthful story.”

Butch Reynolds paid with his reputation and financially

The truth — as presented in “False Positive” — is that Reynolds is an innocent man who has paid figuratively and literally for an injustice.

Reynolds can still tick off the names of sponsors from endorsement deals — Nike, Kroger, the United States Postal Service — and the amounts associated with all these years later. Had those revenues not been wiped out and invested properly he would likely be a multi-millionaire now.

Even with having lost the money, he remained active in the Akron community and his adopted home of Columbus, where he had attended Ohio State, competed in track and even served on the football team’s coaching staff. He is successful, running his own business.

Therein lies inspiration for Al-Amin, who wants people to lean into that aspect of Reynolds’ story.

“Because it's a very inspiring story,” he said. “It really teaches people how family, how faith, how they can sustain you and maintain you and belief in yourself.”

He also wants it to provide some measure of vindication for Reynolds.

“I really hope that, first of all, I think that the majority of people don't really know the story, so I hope the response is like when people are, like, ‘Man, how come I didn't know about this?’” he said. “And I hope it creates some groundswell under Butch to where people want to work with him to help for him to be vindicated reputation-wise and financially.”

No one could blame Reynolds if he had grown bitter over time, even after exoneration in the courts. The professional success, along with personal happiness that includes a wife and children, ensured that did not happen. Understanding things others — such as his idol, Jesse Owens — endured were more severe helped.

Still, he remains frank with his thoughts on the impact the issue has had on him.

“Yes, I wanted to leave this sport. You doggone right, I wanted to leave it, but I couldn't,” Reynolds said. “People know me as an Olympian, they know me as the guy that runs. I can't get away from that, so I had to stay in the process and clear it from within. And that's why I think that doing this [film] will definitely do that.”

Even at almost 60 years old, Reynolds isn’t done running his race.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Akron's Butch Reynolds, an Olympic star, still seeking vindication