Break dancing fostered Black and brown unity. Some of its pioneers worry of erasure

Emceeing, DJing, graffiti, knowledge and break dancing. These are the five elements of one of the most popular and controversial genres that has influenced generations of young artists around the world. On Aug. 11, 1973, in the Bronx, DJ Kool Herc emceed a party that gave birth to the genre that has since taken over the world: hip-hop.

Breaking, or break dancing, as it's referred to in mainstream media, is one of the most important elements to the genre.

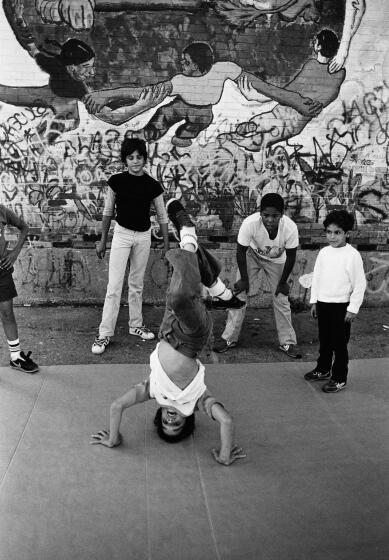

Breaking was created in the Bronx by Black and Puerto Rican youth during the 1980s and has since expanded worldwide. From the streets of the South Bronx to the international Red Bull competition and now the 2024 Paris Olympics, breaking has truly grown and gained influence all over the world.

Read more: 'I've got to find out who I am:' How the Garifuna Museum is reclaiming culture and identity

While it has international recognition, it wasn’t always that way. When breaking first started, it was seen as a nuisance, not an art form.

With the Olympic announcement putting the spotlight on break dancing, two pioneers of the sport discuss the early days of breaking and their hopes for Paris 2024.

At 12 years old, Norman “Normanski” Scott joined one of the most famous breaking groups, the Rock Steady Crew.

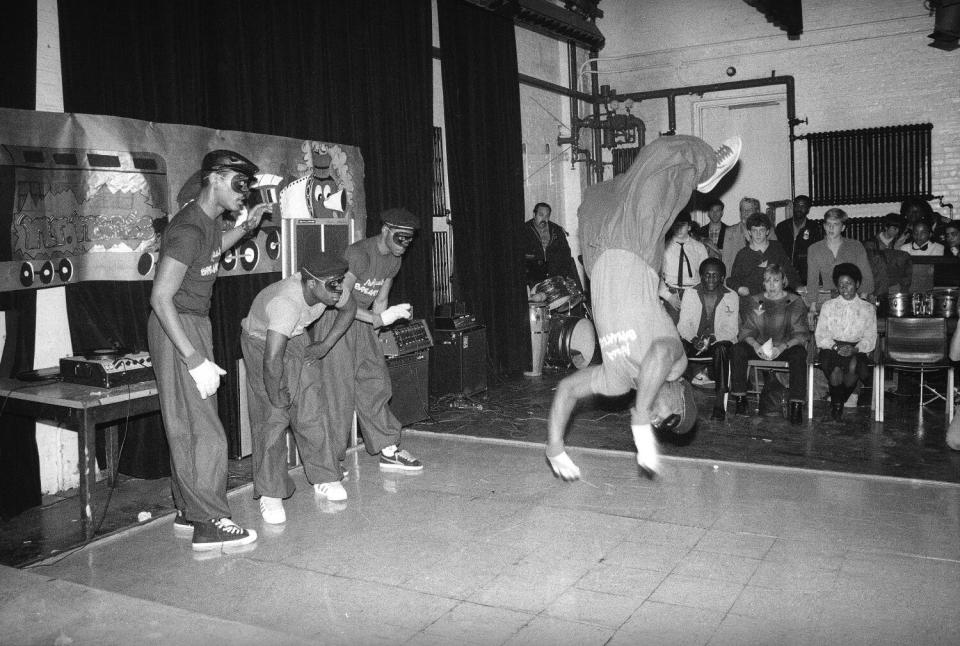

Created by Jimmy Dee and Jimmy Lee, Rock Steady Crew not only revolutionized breaking, but also opened the genre to a national and international audience. Named after a popular hangout spot on West 98th Street in Manhattan, the crew gave birth to some of the most well-known and respected dancers in the world. Ken Swift, Crazy Legs and Frosty Freeze are some of the most recognized dancers who got their start with the group.

When Rock Steady Crew became the first crew featured in a film, 1983's "Flashdance," it helped publicize the group even more. In 1984, the film "Beat Street," which explored hip-hop culture, exposed audiences to the various realities of living in the Bronx and the creation of hip-hop and breaking.

The 1980s were a rough time in many urban communities, but the Bronx faced some of the worst fallout. With the crack epidemic spreading through communities, abandoned buildings being set on fire for the insurance money and gang violence killing the youth, many looked for a positive outlet to not only express themselves, but also gain pride in their communities. Scott sees those same issues from the 1980s reflected in today's community.

“There was a time [when] you [could] go from project to project and battle [by breaking] and now because of gang violence, kids can’t do that,” Scott said. “The art has grown everywhere, but the problem is that the art has died in New York City. Several years ago, I held a break dance competition and none of the kids knew how to break dance.”

Read more: The historic MVP race between Cuban Twins and their unidentical baseball careers

Preserving the art for the communities that started it is of the utmost importance for Scott. He recently partnered with wellness company OYA to ensure spaces where young Black and brown youth can experience the art and learn new skills that will help and guide them throughout their lives.

“New York City has a very rich and diverse history of break dance and graffiti art. It grew and developed in New York City, but it's not really celebrated and remembered that way,” said OYA Chief Executive Mayan Metzler.

With other companies capitalizing on the sport, Scott believes that these various companies owe the communities that created the sport the help needed to grow it.

“In the city, it is a dying art and it's going extinct,” he said. "I think that's sad because we have a cultural responsibility to save something else so beautifully created and that people capitalize.”

Read more: For New York's Ecuadorean diaspora, ecuavoley is a slice of home

Companies such as Red Bull have capitalized by creating the annual Red Bull Breaking Competition that pulls more and more crowds every year.

“Young children are going through so much and there's already so much inequity and inequality. How do you take it away and capitalize off it and don't feel there's a responsibility,” Scott said. “I want to say to them, ‘Help me find an environment to make sure that the art is stored and that the kids who created it have the chance to experience it.’"

In 2020, the International Olympic Committee announced it was adding skateboarding, surfing, sport climbing and breaking as medal sports to the international competition. While this is incredibly big for the art form started by young Black and brown kids from the Bronx, many did not support this announcement.

Jim Schlossnagle, Texas A&M’s head baseball coach, tweeted, “Consider me officially out on the Olympics...breakdancing.” Throughout social media, many criticized the IOC’s decision and believe that breaking isn’t a sport so therefore, it shouldn't be added.

Breaking has been an international sport for years, but an Olympic stage will only propel the sport into the public’s eye even more. Red Bull’s yearly international competition has not only grown in size but also viewership as many seek to learn more about it before the Olympic Games. Since its creation, only four Americans have won, and none were from New York. For pioneers such as Scott, as the sport continues to grow, the question on their mind is: "Will the youth of the communities where breaking started be represented in the upcoming Games?"

“The Black and Hispanic kids in the communities whose parents and grandparents who create it won't be there to compete because of the territorial issues that are in our community today,” Scott said.

Read more: The Latino movie marathon picked by De Los staff

As the countdown to Paris begins, all eyes will be on the newest sport that was started as a way of expression for the youth of a community that was constantly being overlooked.

While breaking was mostly considered a boys’ club, there were countless women in the art form who helped to make it what it is today. Puerto Rican B-Girl pioneer Ana “Rokafella” Garcia broke barriers and helped take the sport even further.

“I saw dancers as I grew up in my neighborhood of El Barrio, so it was part of my environment,” Garcia said. “But then the movie 'Beat Street' showed me that there was magic for all to participate. Baby Love really impresses me and the seed was planted.”

While she had experience with other dance styles including house, salsa and West African, an introduction to Kwikstep helped her connect with others who exposed her to the legacy in hip-hop dance.

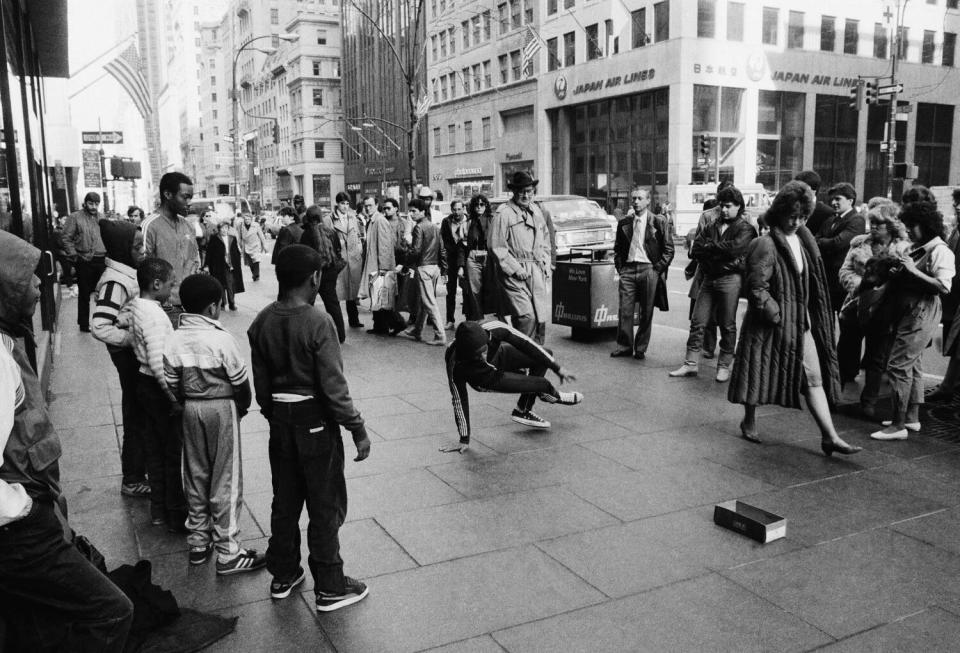

“I connected with breaking in the early ’90s when I began to dance in the streets of Midtown with the original Hitter crews,” Garcia said. “I met Kwikstep in the streets because he also was hitting during the off-time of breaking in NYC.”

As a B-Girl in a male dominated industry, Garcia did face issues when she began to dance downtown.

“I never felt a separation until I went downtown to hit in the streets. I was also showing up to auditions and feeling like the look for female dancers had changed. I wasn't a sexy dancer so it was a moment of pivoting for me so I could do the big moves and represent true power as a woman in the dance community.”

She was able to excel in the industry because she had a strong community supporting her.

“As a B-Girl, I controlled how I dressed and how I interacted with the world. I was fortunate to have met Kwikstep, who respected my spirit and championed for me and any other woman that rolled with our Full Circle squad,” she said. “Since we co-founded a dance organization with the help of Violeta Galagarza, we designed how our platform, presented classic hip-hop and helped to embrace new generations of dancers.”

For younger generations, many aren’t exposed to the art due to the lack of space and programs that teach it.

“Each generation has its footprint so it can expand, but at the core it will never change. Hip-hop is an Afro diasporic voice that calls for respect and at this point after 2020, nothing can erase the rooted aspect of hip-hop in Blackness,” Garcia said. "The Olympics will be another iteration of this dance form and stand alongside the other cultural branches on this tree.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.