Birth of the Jaguars: How Jacksonville's NFL dream became reality in 1993

Note: The Times-Union originally published this article in 2018, commemorating the 25th anniversary of Jacksonville as an NFL city.

Nov. 30, 2018, marked the 25th anniversary of a day that many in Jacksonville never expected to see. On Nov. 30, 1993, the National Football League’s owners cast their vote and proclaimed the Jacksonville Jaguars into existence as the league’s 30th team.

Jacksonville had come close before, from the flare-up of Colt Fever in 1979 to the thrills of the short-lived United States Football League’s Jacksonville Bulls to the failed courtship of the Oilers and the Cardinals and the Falcons. Those were the years that stoked the flames of Northeast Florida’s football fever.

But to bring a team to Jacksonville? To a state that already had two teams, the (usually competitive) Dolphins and the (reliably rotten) Buccaneers? To a city that had never fielded a major league team in baseball, football, basketball or hockey? To a stadium nearly half a century old at the time? The drive to bring the NFL to the First Coast spanned the terms of three mayors (Jake Godbold, Tommy Hazouri and Ed Austin), reaped its reward in the term of a fourth (John Delaney) and drew from the energies of dozens of business leaders and tens of thousands of residents. Few who led the long-shot drive at the start of the 1990s could have envisioned all of the highlights, heartbreaks, celebrations, controversies, expenditures, wins, losses and oddities that kept the city talking for the next quarter-century.

Stadium plans in 2023: Jaguars unveil "stadium of the future" whose cost could hit $1.4 billion

There has still never been a tie.

There has also never been a Super Bowl visit, though the Jaguars have come close enough to tantalize, in the 1996 and 1999 and 2017 seasons, three games ending in their own flavors of agony for Jaguars fans. And, of course, there was the arrival of the Super Bowl itself in 2005, a one-time, cruise ship-aided, Tom Brady-starring extravaganza that almost certainly never would have seen the banks of the St. Johns River in a Jaguars-less world.

But there has been nearly everything else, for better or for worse: Thunder and Lightning, Taylor and MJD, Stroud and Henderson, the games in London, the rumors about moves to London, the rumors about moves to Los Angeles, the chaos of Bottlegate in Cleveland, the rallying cry of “Myles Jack Wasn’t Down,” @BortlesFacts, the tarps, the blackouts, Morten Andersen’s wide-left kick in 1996, the giant video boards and Daily’s Place and the debates over the money to build it all.

The zany antics of Jaxson De Ville, the upsets of Buffalo and Denver on the way to the 1996 AFC Championship game, Fred Taylor’s 90-yard sprint in the 62-7 rout of the Dolphins, the never-ending troubles against tight ends, Mark Brunell’s postseason scramble against the Broncos, David Garrard’s postseason scramble against the Steelers, the incomprehensible lateral-filled finish against the Saints in 2003, the years of rebuilding, the franchise’s sale to Shad Khan and a career of muscle, drive and fire that may yet earn a certain 6-foot-7, 323-pound left tackle a bronze bust in Canton, Ohio. [Note: Tony Boselli was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2022.]

The tragic shooting of Richard Collier, the launch of the Tom Coughlin’s Jay Fund and the Jaguars Foundation, 14-2 in 1999, 2-14 in 2012, Gene Smith’s drafts, the continuing quarterback controversies along the line from Beuerlein to Kessler, Josh Scobee’s 59-yard field goal against the Colts, a kid from Englewood High School growing into an All-Pro cornerback in teal and black, this year’s November nightmare against Ben Roethlisberger’s Steelers and the never-to-be-repeated Times-Union headline “Jaguar whacks leg with team ax.”

Since Paul Tagliabue stepped to the microphone in 1993, the city has never been quite the same. The road to that moment was long, and this is its story.

Memories from 1993: Wayne’s world was a stuck plane

Aug. 15, 1979: Colt Fever was born. Baltimore Colts owner Robert Irsay landed a helicopter on the Gator Bowl field at 6:46 p.m. on Aug. 15, 1979, meeting with Jacksonville mayor Jake Godbold and declaring his interest in moving to the First Coast. Godbold said, “Regardless of what happens tonight, as your mayor, I will do everything in my power during the next 30 days to make sure the Baltimore Colts become the Jacksonville Colts.”

Soon after, Colt Fever died. The Colts remained in Baltimore for four years more, then loaded up the Mayflower vans and hit the road for Indianapolis.

Oct. 14, 1987: Eight years later, it was the turn of Houston Oilers owner Bud Adams to set his sights on Jacksonville. Locked in negotiations with the city of Houston over the Astrodome, where his lease was set to expire at the end of 1987, Adams visited Jacksonville for two days to meet with mayor Tommy Hazouri and city officials and discuss a possible move.

Asked if he could turn down the package that Jacksonville had presented - which included a $125.8 million guarantee over 10 years, raised through sales of 25,000 10-year season tickets - Adams said, “It would be hard to do.“

Hard to do. But Adams did. Even though Houston officials admitted they couldn’t match Jacksonville’s raw numbers, Adams decided to remain in Texas on Oct. 22, after businessmen there launched a drive to lease 72 new luxury boxes at a rate of $30,000 per year. Once again, Jacksonville was left empty-handed.

Aug. 17, 1989: Every game begins with a kickoff, and the Jaguars got theirs in 1989 in a news conference at the Jacksonville Chamber of Commerce.

A group headed by business leader Tom Petway announced the formation of Touchdown Jacksonville! Inc., dedicated to bringing an NFL team to the Gator Bowl. The Touchdown Jacksonville! group also included Jeb Bush, former White House chief of staff Hamilton Jordan and chamber president Arthur “Chick” Sherrer.

The group’s formation initially raised concerns for some, including Mayor Tommy Hazouri and Rick Catlett, executive director of the city’s NFL task force. The reason: Three months earlier, a separate group called Jacksonville/North Florida Leaders Inc. had also launched, headed up by Roy Baker, Bucky Clarkson, Jack Demetree and Lawrence DuBow. The city was concerned about the prospect of bickering ownership groups, and urged them to merge. This they ultimately did by November, building the city’s plans for an expansion team.

Feb. 12, 1991: To play football in the NFL, Jacksonville had to have a stadium, and that was the Gator Bowl. One problem, though: The aging Gator Bowl wasn’t up to NFL standards in several areas, and changing that would require a whole lot of money.

That’s where the Jacksonville City Council stepped in.

The council voted to dedicate $60 million to renovations for the stadium in the event that Jacksonville received an NFL expansion franchise. The plan called for bed taxes and property taxes to help fund the plan, which would include a 30-year lease for the team and would give the team a 65 percent cut of concession receipts. This proposal, with an NFL team still a long way off, passed the council unanimously. Three months later, the bid got further help when Gov. Lawton Chiles signed a bill that could have provided state funding of Gator Bowl renovations. But making these plans a reality would soon present a major challenge for incoming mayor Ed Austin, elected later in the year.

May 22, 1991: Now, things got serious. Expansion was really happening. NFL owners voted to expand the league from 28 to 30 teams for 1994, and formed an expansion committee that would - they expected - determine final candidates by March 1992.

However, the proposal had to overcome resistance from owners like the Buffalo Bills’ Ralph Wilson, who felt 1994 was too early to expand as long as the league still had labor disputes with the NFL Players Association on the horizon. As it turned out, those owners were right.

July 26, 1991: Through the spring and summer, Arthur “Chick” Sherrer had emerged as the public face of Touchdown Jacksonville!, campaigning among NFL cities and declaring Jacksonville the front-runner. One week earlier, Sherrer had said, “We’re the No. 1 candidate and we can prove it.”

On this date, though, Sherrer appeared in the headlines for other reasons: He was accused of offering an undercover policewoman $40 for sex at 6:20 p.m. along a road then still called Phillips Highway. Five days later, at a press conference, Sherrer, the former president of the Chamber of Commerce, resigned his position. Four months later, on Nov. 6, he pleaded no contest to a lesser charge, breach of peace.

The news did nothing to change the fundamentals of Jacksonville’s bid. The status of the stadium, ownership and ticket sales all remained as before. But now, people who didn’t even know Jacksonville was pursuing a team were reading news about the bid, and it wasn’t good news. The potential damage to the bid’s image was harder to calculate. And Touchdown Jacksonville! now needed a new leader.

For most of the coming months, that man would be Tom Petway.

Sept. 30, 1991: On the last day before the deadline for expansion ownership applications, Touchdown Jacksonville! Inc. became Touchdown Jacksonville! Ltd., with nine members and Tom Petway as general partner. The group also included Jeb Bush, Lawrence DuBow, Earl Hadlow, Preston Haskell, Donald W. McArthur Jr. and Charles D. Towers.

There was also a new name - J. Wayne Weaver, president and CEO of women’s footwear business Fisher Camuto Group, who joined Touchdown Jacksonville! along with his brother, Ronald. The combined net worth of the group was estimated at some $500 million.

At the time, Weaver’s role was comparatively limited. Petway, as general partner, held the largest stake. But the presence of Weaver, who brought considerable financial assets and a big-business background, soon began to gain attention. Three weeks later, the group added another key figure in hotel executive David Seldin, who took over as the organization’s president.

Touchdown Jacksonville! was taking shape.

Dec. 6, 1991: NFL hopes were still a long way off, but if they ever came to fruition, fans at least learned what the name would be: the Jaguars. At the time, Touchdown Jacksonville! Ltd. vice president Rick Catlett said they selected Jaguars “because no other professional sports team has it,” as well as because of a 24-year-old jaguar - then the oldest one living in North America - at the Jacksonville Zoo.

The other three finalists were the Sharks, Panthers and Stingrays.

Dec. 10, 1991: This was Jacksonville’s first big chance. The Touchdown Jacksonville! group traveled to New York for presentations before NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue and league president Neil Austrian, one of five cities - along with Charlotte, Nashville, Oakland and Sacramento - to present its case that day.

TD Jax went all out. The group put together a 10-minute film, with Academy Award-winning actor James Earl Jones as narrator, and even included footage from the sold-out 1941 Gator Bowl that matched Miami and Auburn. At the end of it all, Tom Petway was confident: “I can’t imagine not being on the short list,” he said.

March 17, 1992: Cut-down day. Eleven cities had applied for NFL expansion, and the league’s expansion committee was ready to trim that list down. By the day’s end, Jacksonville was still standing, along with Baltimore, Charlotte, Memphis, Oakland, Sacramento and St. Louis. Not making the cut, though, were Honolulu, Nashville, Raleigh-Durham and San Antonio. The league also confirmed plans to cut that list further in May.

While Jacksonville surmounted this obstacle, the story nearly turned out very differently. It later surfaced that Jacksonville was nearly among the cities cut, and it took a four-hour meeting with an NFL delegation headed by Roger Goodell - then the league’s executive director for club relations - to persuade the league of the merits of the city’s bid, particularly its stadium plans.

The First Coast had cleared its first major hurdle. There were more to come.

May 19, 1992: Cut-down day, again. Now the NFL slashed its list from seven to five. And there was reason for worry on the First Coast. Just days earlier, several members of a panel of NFL writers told the Times-Union that they expected Jacksonville to stumble at this point. No matter what Touchdown Jacksonville! did, the group couldn’t nullify the city’s small market size, and for many, that was viewed as a barrier too high to clear.

The cities sliced from the list this time: Oakland and Sacramento, the California pair. Jacksonville could breathe a sigh of relief, for now.

Yet over the summer, other signs were building. The fight between the league and the players’ union, a fight that ultimately led to free agency, was brewing. That was significant for Jacksonville, because more and more, word was going around that the expansion timetable could move back as the league scrambled to address the labor situation.

Oct. 20, 1992: Delay of game. On the field, it backs a team up five yards. During the expansion race, it backed Jacksonville up one year.

The conflict between ownership and players was boiling over. No collective bargaining agreement was in place. And a court had struck down the league’s preliminary free agency system, called Plan B, due to antitrust regulations.

With further cases flying into the courts, the league voted to place expansion on hold for at least a year. The process had already been pushed back until the end of 1992 at a September meeting. Now, Jacksonville and other cities were looking at decision time, at best, in late 1993, with first kickoff no earlier than 1995 - and that was based on the assumption that the league and union could come to terms.

Dec. 22, 1992: An early Christmas present for football fans in Jacksonville, and many others around the country: The NFL and the NFL Players Association announced a preliminary agreement on a five-year labor contract, a deal that became official two weeks later on Jan. 6, 1993. The significance: That meant that football was finally at labor peace.

Now, after a hiatus of several months, the expansion clock could start ticking again, toward a first kickoff in 1995.

March 18, 1993: Now, Wayne Weaver stepped to the front of Jacksonville’s expansion drive. A partner in Touchdown Jacksonville! for some 18 months, the shoe executive emerged as the group’s new general partner, taking over from Tom Petway and becoming the majority owner of the prospective franchise. The Jaguars now had their money man.

As Petway put it, “We’re changing our formation to give our financial fullback the ball, and I assure you he can fill the shoes.“

That was important. Starting an NFL franchise meant more than just the expenses of stadium renovations, salaries and similar expenses. The league was also asking for a franchise fee of roughly $140 million, plus $16 million in interest. Also, expansion teams would not receive full shares of television revenues for their first three years, which would make a dent in club incomes of nearly $50 million more. Weaver, whose net worth was estimated at around $250 million, had the resources to handle that expense on his own, something that wasn’t true of all of the ownership groups. Even Weaver, though, acknowledged it wouldn’t be easy.

March 23, 1993: Jacksonville, and the rest of the expansion contenders, now learned when the NFL planned to make its decision. With labor peace secured, the NFL’s expansion committee announced a new timetable for the decision at its meeting in Palm Desert, Calif.

The plan: The NFL’s full membership would set franchise fees in late May, followed by presentations from each city in September or October and a final decision on the cities later in fall.

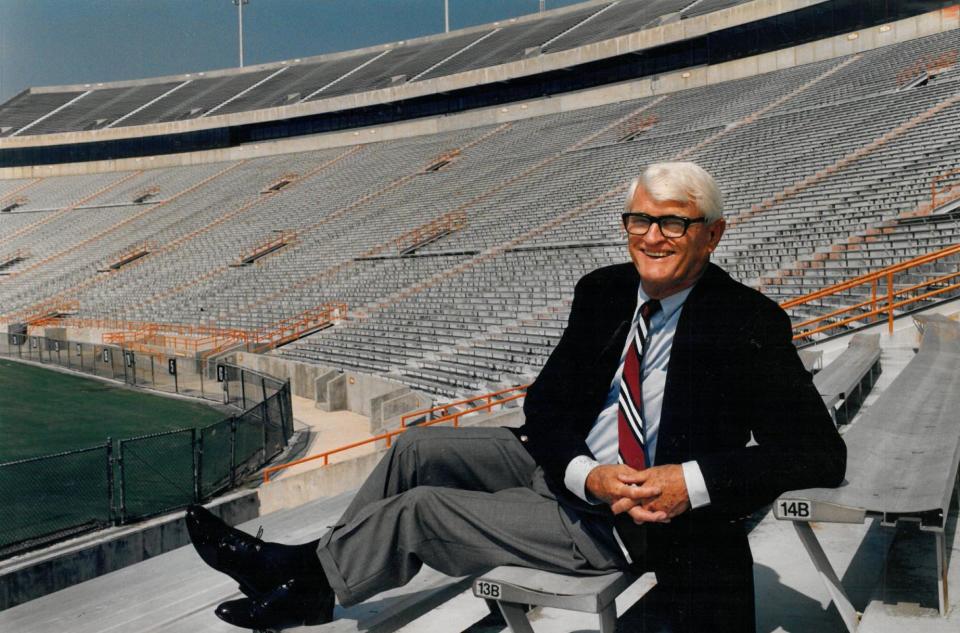

Meanwhile, issues were building at home. Mayor Ed Austin toured the Gator Bowl as part of his River City Renaissance program. Was the amount the city had budgeted for the stadium’s renovation going to be enough?

April 12, 1993: Now, it was the NFL’s turn to come to Jacksonville. Three NFL officials - director of club administration Joe Ellis, special projects assistant Ken Saunders and vice president of operations Roger Goodell, now the commissioner - came to the First Coast as part of the standard tour for prospective expansion cities. The three met with Wayne Weaver, Tom Petway and David Seldin of Touchdown Jacksonville! at the Gator Bowl, then boarded a helicopter in the end zone for a four-stop tour throughout the area.

The destinations: The TPC Sawgrass Stadium Course, where all three NFL representatives hit balls at the 17th hole, and all found the water. Merrill Lynch headquarters on the Southside. The Mayo Clinic. The Blount Island port facilities, now JaxPort. At the end, the TD Jax representatives hoped, they had shown the NFL an up-close picture of what Jacksonville was all about.

“I think they were impressed,” Petway told the Times-Union. “Hopefully, the next time that they come back will be when they announce that we have a team.“

May 12, 1993: The NFL’s visiting delegation might have been impressed with some aspects of Jacksonville. But the Gator Bowl wasn’t one of them.

Now, Touchdown Jacksonville! had news for the city. The $60 million price tag on the Gator Bowl’s upgrades wasn’t going to be enough. Now, TD Jax president David Seldin said the NFL had urged the group to get that number boosted if they wanted an expansion franchise. In his words, “The NFL has suggested our current plan is not competitive under the scope of the current renovations, so we feel we must listen when the NFL tells us the stadium isn’t competitive.”

The request: An extra $30 million, a big jump in the price tag, to replace stands behind the north and south end zones. Because the franchise fees were higher than TD Jax had initially expected, Seldin said, the group needed City Hall to contribute to the project, by tacking that money onto the $49 million already budgeted as part of the previously-approved River City Renaissance plan.

That meant more talks with the city. And that wasn’t going to be easy.

June 4, 1993: Trouble was brewing, and Touchdown Jacksonville! was watching its relationship with the city head toward the rocks.

The expansion group had sought to revise its lease for the Gator Bowl, saying $60 million would no longer be adequate to upgrade the aging stadium. Mayor Ed Austin, though, wasn’t interested. He felt the terms placed an undue burden on taxpayers, did not specifically guard against the possibility the team could move prior to the lease’s expiration, and carried significant financial and legal risks. And those risks were mounting.

So on this day, Austin put his foot down. In a statement issued by the Mayor’s Office, he said, “The Touchdown Jacksonville lease proposal in its current form is, in my judgment, unacceptable. While I maintain a strong determination to do everything within my power to help obtain a professional football franchise, this proposal would expose this city to unreasonable financial and legal risks.“

Austin said that he was open to some changes, but that those changes had to be in the best interests of the public. He also laid down five counter-requests, including demands that TD Jax would pay for any cost overruns in construction and wouldn’t leave town before the 25-to-30-year bond issue was paid off.

The headline in the next day’s Times-Union: “Austin says no to TD Jax.” It was about to get ugly.

June 25, 1993: The split between Touchdown Jacksonville! and the city degenerated into open feuding. The expansion bid lay in tatters.

The quotes of the day tell the story.

From Mayor Ed Austin: “We’re not going to be intimidated into a bad deal.“

From Touchdown Jacksonville! itself, in an open letter to residents: “Let there be no doubt, Mayor Austin knew all along, all during [discussions on the River City] Renaissance, and tried to threaten and bully TDJ into silence.“

From city finance director Mike Weinstein: “I’m saddened that TD Jax has resorted to lies and false allegations to try and find someone to blame for their miscalculations and lack of professionalism. For these owners of TD Jax to make these type of statements at this time is an embarrassment.“

From Wayne Weaver: “Quite honestly, I’m frustrated with the lack of vision the Mayor’s Office has for the city.“From John Delaney, chief of staff to Austin: “With TD Jax and this go-around, it’s over.“

At issue: Many things. The cost of Gator Bowl upgrades, which a study commissioned by the city said might cost as much as $148 million - a figure termed “absolutely absurd” by councilman John Crescimbeni. The amount of revenue the team would produce over its 30-year lease. The level of trust, or lack thereof, between the prospective ownership group and the city. On June 25, those factors pushed Jacksonville’s bid to the brink of extinction.

The council expressed shock at the high dollar figure. Austin said he would veto the lease even if the council passed it. They didn’t. Negotiations broke down.

By evening, Weaver said, “It will take a miracle at this point for this thing to come back to life.“

July 21, 1993: That was it. Wayne Weaver had had enough. Tired of the quarreling with the mayor’s office. Tired of the bickering with the city council. Tired of the slow and frustrating pace of ticket sales. Tired of the goalposts that never seemed to stop moving.

On this day, the head of Touchdown Jacksonville! called it quits.

The situation hadn’t looked hopeless a few days earlier, even a few hours. After the council’s initial reluctance to back the lease, TD Jax had returned to negotiations with Mayor Ed Austin and reached a tentative agreement on a revised lease proposal July 1. That deal would have set $112.3 million as the city’s maximum expenses in Gator Bowl renovations, and much of the council appeared to support the plan.

Aside from the central importance of the lease in itself, TD Jax desperately needed good news to rekindle enthusiasm that had gone tepid as the bid dangled in limbo. On July 19, the group reported that only 18 of 68 luxury suites had been sold, along with just 2,019 of 10,000 club seats, prompting former mayor Jake Godbold to offer his support to the ticket drive. But at least the lease was now before the council. TD Jax and the city planned a rally at the Jacksonville Landing to celebrate the lease’s expected approval.

Then it all fell apart.

During discussions before the city council, Jacksonville general counsel Charles Arnold proposed an new provision to the lease, one that would absolutely cap the city’s liability at $112.3 million. If the cost exceeded that, under Arnold’s proposal, the city could scale back the renovations.

But Touchdown Jacksonville! declared that unacceptable. As TD Jax attorney Paul Harden said, “We will not sign the lease with that change. The NFL tells us what we need to get a team. We need to rely on the fact that you are going to build that stadium for us.“

To many members of the council, it appeared that the $112.3 million cap wasn’t a cap at all. By a 12-7 vote, the council chose to send the lease back to committee. What Weaver thought was a done deal was simply done, period.

That night, Weaver called a news conference at 9 p.m. at the Touchdown Jacksonville! office. It did not last long. It included words that no one earlier in the day expected him to say:

“Today began with great expectations. Those expectations were not fulfilled.

Thank you, Jacksonville.

Thank you to the 5,000 fans who stood in the rain at the Landing tonight to join the Jaguars Booster Club.

I love Jacksonville.

My partners in Touchdown Jacksonville! love Jacksonville.

I cannot tell you how disappointed we all are that our efforts to bring the NFL to Jacksonville are over. Tomorrow, we will instruct First Union to return the over $2 million of deposits that our suite holders and club seat holders made.

A special thanks to those companies and individuals.

A special thanks to our many volunteers.

Good night.“

Touchdown Jacksonville! was walking off the field. A five-team race was down to four.

TD Jax president David Seldin said, “We’re out of business. We don’t care what people say about us anymore. It’s over.“

Aug. 24, 1993: It wasn’t over.

Behind the scenes, midway through August, the city and Touchdown Jacksonville! resumed talks about a reviving the bid with a revised lease, prompted by city councilman Don Davis as well as NFL officials like vice president of operations Roger Goodell.

The league saw weaknesses in the other bids. The NFL didn’t want Jacksonville and Wayne Weaver to go away. Within a few days of behind-the-scenes discussions, negotiators from TD Jax and the city had hammered out a preliminary lease proposal with a cap of $121 million to renovate the Gator Bowl.

That was just one part of the equation. Getting the city council to approve it Aug. 24 - the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Andrew - was another. The council had rejected the earlier version when the dollar figure was $112 million. Given an even higher figure, would they balk again? Public opinion was uncertain. An admittedly unscientific collection of phone responses through the Times-Union’s old InfoTouch system came through at about 50 percent support.

TD Jax needed more support than that on the council. On the night of Aug. 24, they got it. The revised lease - 30 years at the stadium, with the team covering all cost overruns beyond $121 million - passed the council by a vote of 14-4.

The next day, the Times-Union carried the headline: “It’s real.“

But the challenge was just beginning.

Now, to persuade Weaver to return to the contest, the team had a whole lot of tickets to sell, and a short time to do it.

Sept. 3, 1993: The sellout. Once Touchdown Jacksonville! and the city agreed on their lease, the clock began ticking.

The deadline: overnight Sept. 3. The target: Selling 10,000 club seats, a needed step to convince the NFL of the bid’s economic viability. Wayne Weaver would pick up the final 1,000 if TD Jax got to 9,000, making the task marginally easier, but not much: That timeline still required fans to purchase club seats at the rate of one every 96 seconds.

Could they do it? Those tickets weren’t selling well even before the expansion drive broke down in July. By contrast, club seat sales couldn’t have been better in rival Charlotte, which had already sold its entire allocation of 8,314. And the cost wasn’t exactly cheap: $750 as a deposit, plus $750 more if and when the NFL actually awarded Jacksonville a franchise. Lined up next to the average 1993 Jacksonville salary of $24,441, as computed by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, that expenditure would gobble up more than 6 percent of an average worker’s annual income.

To spark the bid, a coalition of business leaders created what was possibly the most intensive sales drive in the city’s history.

The group was NFL Now!, and its heads were Times-Union publisher Carl Cannon and Jacksonville Chamber of Commerce chairman Adam Herbert. Mustering a small army of volunteers, they reconnected with fans who had previously bought tickets in the initial drive and launched a full-scale media blitz - 20 pages of advertising in the Times-Union, public service announcements on local broadcast stations, billboards spread around town, even a dedicated extension on the Times-Union’s old InfoTouch system to link fans with information on the club seat push.

Seven Jacksonville television stations simultaneously aired a five-minute special promoting the club seats.

They set up a van in the parking lot at the Regency Square Mall, then a bustling hub of shoppers from all across the city, selling eight club seats in the first five minutes of operation there.

And it was working. The full-scale sales blitz pumped up Jaguars mania to full force. Within the first day, NFL Now! had already sold 1,456 club seats. Then, 1,104 on the second day. After a third-day slump to 550, the next two days brought in a total of 2,962.

The halfway point: 6,072 out of 9,000 seats.

But there was trouble in the air. Or, more accurately, in the water. Hurricane Emily, a Category 3 storm with winds swirling to 115 miles per hour, loomed dangerously offshore, tracking due west after passing south of Bermuda.

Would the hurricane threaten the First Coast, blast Jacksonville residents and slow the sales pace to a crawl? By the last two days of August, the steering currents of the North Atlantic Ocean answered the question. Emily began to turn northwestward, grazing North Carolina’s Outer Banks before accelerating out to sea.

Emily or no Emily, though, ticket sales were slowing down.

Fans purchased just 730 tickets on its sixth day and 461 on the seventh. With barely 48 hours remaining, NFL Now! pulled out its final closing push. Herbert termed it the “two-minute drill.“

Three banks - Barnett Bank, First Union and American National Bank - offered special no-interest, no-fee loans for fans to purchase club seats. All of their branches, plus SunBank as well, turned into drop-off sites for checks. The Times-Union advertising department dispatched couriers to pick up application forms and checks. Even Domino’s Pizza joined the drive. Call with a completed application form and check, and Domino’s agreed to send a delivery driver to pick it up - and drop off a free medium cheese pizza as part of the bargain.

NFL Now! arranged for six employees at accounting firm Arthur Andersen to fill 400 envelopes with application forms and information on club seats, then hand-delivered those envelopes to every home at Jacksonville Golf and Country Club. The group sent a van on an out-of-the-box if relatively unfruitful tour through Southeast Georgia Sept. 1, selling a total of eight tickets in Waycross and Brunswick.

But what if NFL Now! got to the evening of Sept. 3, closing time, and it still wasn’t enough? Committee member Rick Catlett was prepared: “If we don’t have 9,000 tickets,” he said, “we’ll stand out there with a bag and collect checks just like the IRS does at tax time.“

No IRS moment necessary. At 8:30 p.m. on Sept. 3, NFL Now! tallied the numbers. The total: 9,737, more than enough to bring Weaver back on board. In fact, once all the applications were processed in a state that would return to the headlines seven years later as the home of the recount, the number of club seats sold climbed to 10,112 - more than the actual number of seats available.

The Barnett Tower that night lit up with the words: NFL Now.

Sept. 7, 1993: The club seats were sold. Jacksonville was back in the expansion game. Now, Wayne Weaver returned from Connecticut, coming back to the Gator Bowl to sign the revised lease agreement with representatives of the city. Residents greeted Weaver at Jacksonville International Airport, with some waving a sign that read, “Jacksonville is Wayne’s World.“

Now, Jacksonville’s bid was back on firm footing. Weaver noted that the city’s successful effort in club seat sales had attracted attention throughout the NFL, saying, “They’re in awe. No other city has been able to meet what we’ve done here.“

But with only two weeks until the NFL’s due date for expansion presentations, the Touchdown Jacksonville! team had to get to work - fast.

Sept. 21, 1993: Presentation day arrived for Touchdown Jacksonville! Prospective owner Wayne Weaver led a six-man delegation to make Jacksonville’s case before the NFL’s expansion and finance committees in Chicago. In a one-hour pitch, they promoted the stability of the bid’s ownership group, the plans for redeveloping the Gator Bowl and the passion of Jacksonville’s football fans.

Weaver brought the full squad for this presentation, which all knew would go far toward making or breaking the city’s hopes. Joining Weaver were Jacksonville Mayor Ed Austin, minority partner Tom Petway, TD Jax president David Seldin, Times-Union publisher Carl Cannon and Chicago-based developer Vincent Ziolkowski. Cannon had powered the NFL Now! effort to sell club seats, while Ziolkowski was a consultant working for a contractor involved in Gator Bowl renovation plans.

Jacksonville stood third in line to make its presentation. St. Louis, which was still viewed as the favorite, went first, followed by Baltimore. Charlotte and Memphis were assigned to present the following day. The city’s concerns were many. St. Louis, as before, stood as the favorite. Baltimore came out with an intensely confident presentation from prospective owner Leonard “Boogie” Weinglass, who said, “The city is a lock. The city has the goods. You can rest assured the city is going to get a team.“

Aside from Baltimore’s bluster, Jacksonville was also short one key ally: Bucs owner Hugh Culverhouse, who had a home in Jacksonville and was viewed as a supporter of the bid, was unable to attend due to illness. Without Culverhouse, how many backers on the committees did the city have? They didn’t know.

Still, Weaver expressed confidence. “I know a lot about body language and I am very excited with what I saw in that room. I’ve always felt good about Jacksonville’s chances, but after the presentation, I feel even better. We think we moved the Jacksonville case pretty far up the ladder. We’re very comfortable Jacksonville will be awarded one of the two franchises.”

Weaver had one more possible trump card to play. That day, Touchdown Jacksonville! announced one more addition to its ownership group in former Kansas City Chiefs safety Deron Cherry, who gave the group a respected connection to the on-field aspect of the game.

The work was done. Now, the waiting began.

Oct. 26, 1993: Decision Day I. The meeting day had arrived. NFL owners gathered in Chicago to determine the fates of the expansion bids, and Jacksonville fans waited anxiously for any scraps of news from the Windy City.

Would the Jaguars become a reality?

Prospective owner Wayne Weaver and his Touchdown Jacksonville! delegation got one more presentation, a short one. Fifteen minutes to make one last push to separate Jacksonville from the expansion rivals, from Baltimore, Charlotte, Memphis and St. Louis. Then Weaver, too, like the fans back home, would join the ranks of the waiting.Jacksonville knew what the critics thought, knew the city was still viewed as a long shot. But, on this day, prospective Jaguars fans at least expected to learn the NFL’s answer once and for all. Yes or no?

Instead... nothing.

NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue made the announcement that Charlotte would become the 29th expansion team, but the other choice would be delayed until a subsequent owners’ meeting Nov. 30, five weeks away. And that didn’t go over well on the First Coast, where the Times-Union reported that “a chorus of obscenities” filled sports bars when Tagliabue proclaimed the news.

The Times-Union’s headline the next day: “We’re on hold.“

Fans in Jacksonville and other cities cried foul, accusing the NFL of extending the race purely to give St. Louis a chance to restore harmony to its squabbling ownership factions. For many experts, the thinking was that the NFL would choose one old city (St. Louis) and one new one. So if there was one spot for a newcomer, and Charlotte had just snatched it, then Jacksonville’s chances would be dead on arrival on Nov. 30.

Wayne Weaver wasn’t happy, either. “We’re very disappointed in the way things worked out,” he said. “We came here with the idea that there would be a decision, whether we’d be in or out. We still don’t know that, so it’s a bitter pill to swallow.“

City leaders also responded after the NFL’s announcement. Former mayor Tommy Hazouri held out little hope that the NFL would select Jacksonville. His view: The city needed to be ready to move on for now. “We have a number of other priorities that we must address,” Hazouri said. “Whether we get a team today or not, our goal should be to build a great city. If we do that, eventually they will come, and so will the extraordinary way of life.“

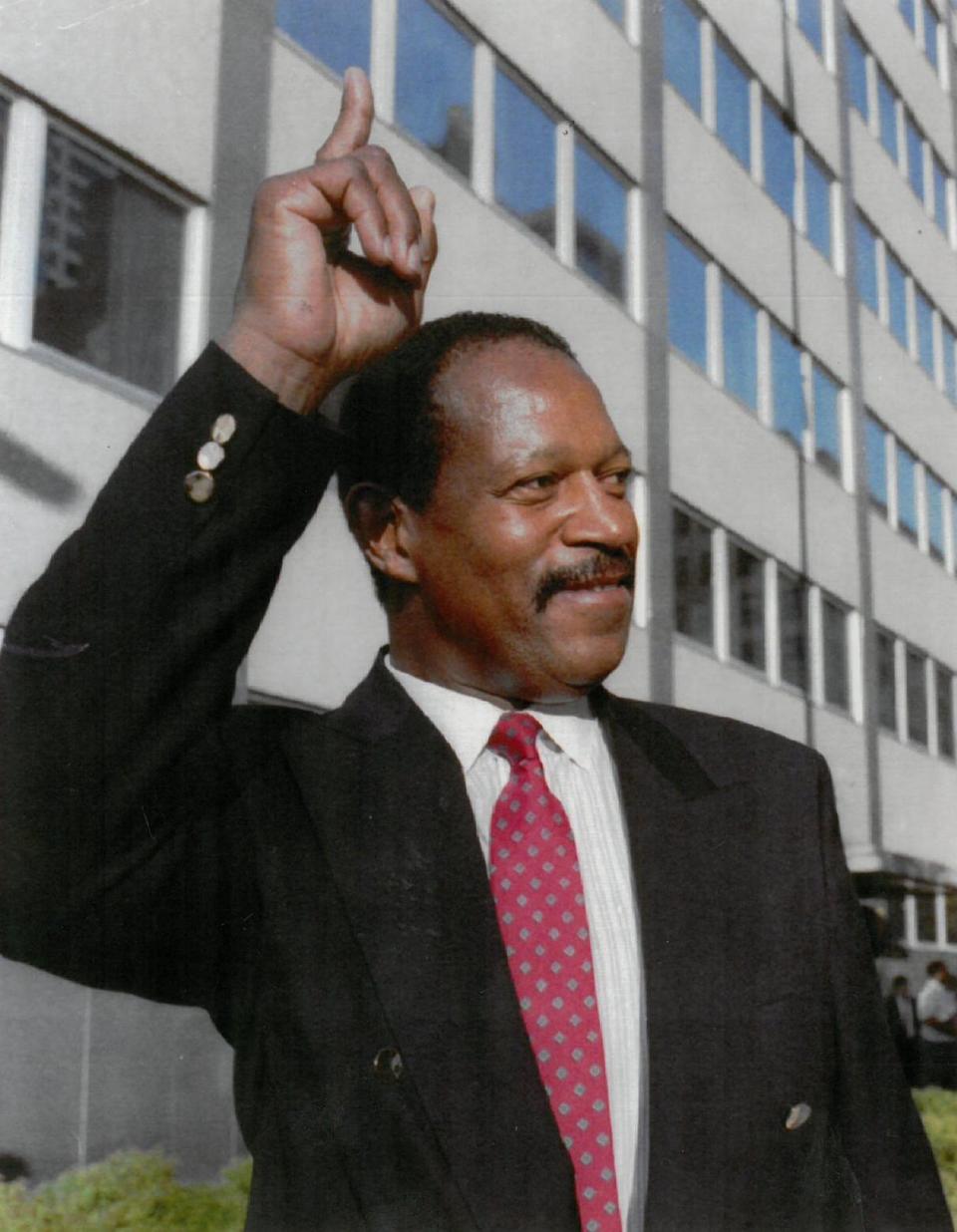

Chamber of Commerce chairman Adam Herbert said, “The chamber continues to be optimistic about our chances... But we also recognize that it will be a major challenge competing against Baltimore & St. Louis in particular.“

But, maybe, there was another possibility, one that didn’t need the NFL. City councilman Eric Smith had been tracking news from elsewhere in North America, where the Canadian Football League had begun plans for expansion to the United States, starting in Sacramento. Maybe, Smith suggested, Jacksonville should join the likes of Las Vegas, San Antonio and Shreveport as bidders for CFL franchises.

At any rate, Smith felt the Jacksonville wouldn’t have to put up with the NFL’s politics, echoing sentiments widespread around Northeast Florida at the time. “The NFL lied,” Smith said. “They lured Jacksonville back into the race to get a better deal from the other cities.“

Even Jake Godbold, long among the most die-hard of the city’s die-hard football backers, said Jacksonville was “out of it.” His hope, though, was that the disappointment of Decision Day I would someday bear fruit down the road.

“My dream is we get a team before I die,” the former mayor said.

He did.

Nov. 30, 1993: Charlotte was already the 29th NFL city. Someone else, whether Baltimore or Jacksonville or Memphis or St. Louis, was about to become the 30th, at an NFL owners’ meeting amid the pressure-cooker tension of a Tuesday afternoon in Chicago.

Wayne Weaver and his colleagues in the Touchdown Jacksonville! delegation were waiting inside the Hyatt Regency O’Hare hotel there, waiting for news. Weaver called it the most nervous time in his life. But rumors were trickling in, little by little. The expansion committee liked Jacksonville. The finance committee, too. The news was good. The full vote was coming. Then, just after 2:30 p.m., the NFL director of security stepped out of an elevator to walk to the 27th-floor TD Jax suite.

Touchdown, Jacksonville.

The time was 4:12 p.m. when NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue stepped to the microphone and declared the news that had already begun seeping out to the world. Jacksonville was a major league city, the 30th in the NFL, clearing the full membership vote by a margin of 26-2.

The mission was accomplished.

That night, Weaver and his TD Jax! colleagues flew back to Jacksonville, greeted by a crowd of thousands at the Gator Bowl for the new celebration. A near-frenzy began on Jaguars merchandise. Retailers couldn’t keep Jags gear on the shelves. The Times-Union even printed a special Jaguars Extra edition, with the headline, “We did it!“

The Dec. 1, 1993 Times-Union headline told the story, with a tip of the hat to Al Michaels: “Do you believe in miracles? YES!!“

Or the front page of Sports: “A day we won’t forget.“

Or, simply, the front of the special Jaguar Extra edition printed that day: “We did it!“

Epilogue: That November day in Chicago marked the end of Jacksonville’s quest to obtain a franchise. But for the Jaguars themselves, day one was only the beginning.

From that day, the milestones unfolded rapidly. The start of demolition and construction at the Gator Bowl, turning it into a shiny teal Jacksonville Municipal Stadium in time for the summer of 1995. The hiring of Boston College’s Tom Coughlin as the first coach, already prominent in the area after his shock of Notre Dame - only 10 days before the expansion announcement - paved the way for Charlie Ward, Derrick Brooks and Florida State to win a first national title for Bobby Bowden. The first player signings on Dec. 15, 1994: Shannon Baker, Hillary Butler, Ferric Collons, Greg Huntington, Ernie Logan, Rickie Shaw, Jason Simmons, Ricky Sutton, Chris Williams and Randy Jordan, who entered the books as the scorer of the first touchdown. The expansion draft on Feb. 15, 1995, when the Jaguars made Steve Beuerlein their first quarterback. The completion of the stadium. The Hall of Fame Game in Canton, Ohio, on July 29, 1995, the first time the Jaguars took the field. The first home preseason game, Aug. 18 against the Rams. At long last, the franchise debut against the Houston Oilers on Sept. 3, 1995.

In one of those strange twists, all of the other finalists turned into NFL cities themselves within four years. Two of the cities won Super Bowls. Two lost their teams, one after a single year as it had expected, the other after two decades. Two of them employed Jeff Fisher as a head coach. Charlotte began its journey when the Panthers in 1995. St. Louis welcomed the Rams from California in time for 1995, then watched as the Rams hit the road again to return west two decades later. Baltimore lured Browns owner Art Modell at the end of 1995 in a move that spawned boos by the tens of thousands, a relocation so contentious that the league quickly awarded Cleveland a new franchise in 1999. Even long shot Memphis briefly got NFL football, hosting the Oilers - now the Titans - at the Liberty Bowl for the 1997 season before Bud Adams made Nashville the team’s long-term home.

Eventually, the central figures of the franchise’s start departed one by one. David Seldin stepped down as team president in 1997 and now serves as managing partner of venture capital firm Anzu Partners. Tom Coughlin lost his coaching job after the 2002 season, though he returned to the front office nearly 15 years later. Mark Brunell, quarterback of the playoff teams from 1996 to 1999, was traded to the Redskins in 2004. The last of the original Jaguars players, Jimmy Smith, retired in 2006. Paul Tagliabue stepped aside as NFL commissioner in 2006, to be replaced by Roger Goodell, the man never far from the center of the league’s expansion drive. Ed Austin, the mayor who at times sparred with Touchdown Jacksonville! management but ultimately became a key backer alongside the prospective owners at the Chicago announcement, died at age 84 in 2011.

Even Wayne Weaver didn’t remain in control forever. On Nov. 29, 2011, 17 years and 364 days after he had achieved his NFL dream, he announced he was selling the Jaguars. The purchaser: Shad Khan, whose automotive part company, Flex-N-Gate, is based about 125 miles south of the hotel where Weaver and his colleagues learned their NFL fate. Khan also acquired the shares of the other limited partners, including some, like Tom Petway and Lawrence DuBow, who were Touchdown Jacksonville! originals. The sale price was estimated at $770 million. Within two years, the Jaguars had spread their pawprints onto a second continent.

Friday will mark the start of the Jaguars’ second quarter-century. The highlights and the lowlights are not over. The debates over money and finances and the franchise’s long-term future are not over - witness the continuing speculation over Lot J and London and the hunt for revenue. The wins, more than likely, are also not over, no matter how much it may feel like it for the frustrated Jaguar fans of today.

The story is not over. But without one afternoon in Chicago 25 years ago, most of it never would have happened.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Jacksonville Jaguars: The road to the NFL franchise’s 1993 founding