What baseball overseas looks like through Canadian eyes

For a young Canadian baseball player the template for success is, theoretically, quite simple.

A cocktail of talent and hard work gets you noticed by scouts, you get drafted and either choose college or the pros, spend a couple of years in the minors and boom you’ve got yourself a lengthy and lucrative major-league career. That, in exceedingly broad strokes, is what happened with guys like Joey Votto, Justin Morneau and Russell Martin.

However, a career in professional baseball — like virtually any other career — doesn’t necessarily have a linear progression. There are roadblocks, detours and retracing of steps. The options are more varied than just minor leagues or major leagues.

As a result, many ballplayers find themselves in far flung corners of the world plying their trade whether they’re on the way up, the way down, or adrift without an obvious trajectory. This is the story of Canadians who found themselves playing the game they love in places from Japan, to Mexico, to Sweden: how they got there, what they experienced and what they missed about the Great White North.

How you wind up overseas

Playing abroad is never Plan A, but it can become an appealing Plan B in a hurry. For players struggling to crack the major leagues, it’s difficult to get by on paltry minor-league salaries — especially if you have a family to support.

Scott Mathieson, a star reliever with the Yomiuri Giants for the last six seasons, was first lured to Japan for just that reason.

“I realized I needed to be making some money or start figuring out what I was going to do with my life,” the Vancouver native says. “I had just got married and we were talking about having a family so I chose the money and went to Japan.”

There’s also the matter of opportunity. If you feel like you career is hitting neutral stateside, playing across the Pacific could let you blossom in a bigger role.

“For me the allure of playing in Asia was that I believed that I am an everyday player,” explains Jamie Romak, who played in Japan in 2016 and South Korea last year. “I had reached a point in the States where my opportunities in the major leagues were likely to be in a bench role.”

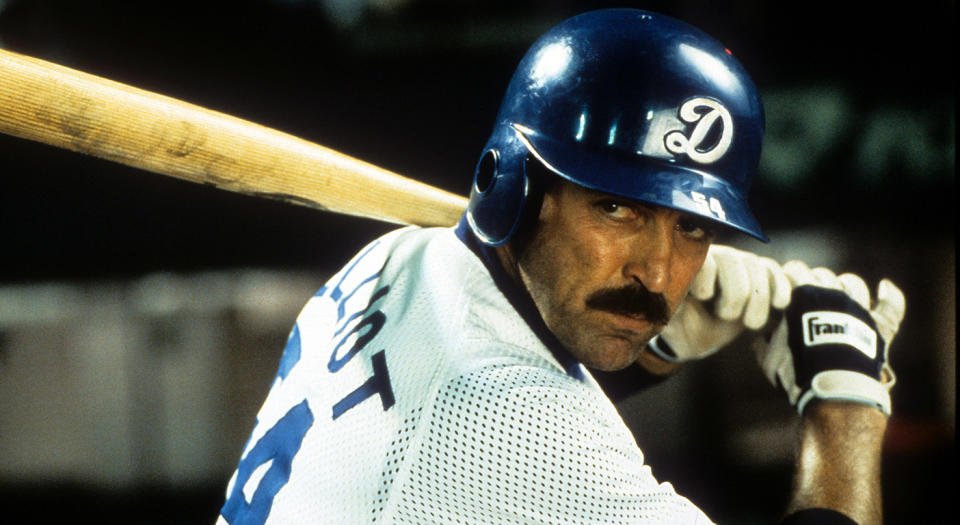

Sometimes it’s dumb luck that puts the idea in your head. When former Toronto Blue Jay Rob Ducey was grinding his way through the Texas Rangers’ minor-league system and all it took was seeing a movie about baseball in Japan to get the gears in his mind going.

“In 1994 I was in Triple-A with the Texas Rangers and I ended up watching that Tom Selleck movie, Mr. Baseball, and I came into the clubhouse the next day and asked one of my teammates what it was like because it looked kind of appealing — it was a neat story. He told me, ‘You should look into that, you’d enjoy it over there.'”

A year later he was lacing them up for the Nippon Ham Fighters.

Last but not least, there’s alway personal connections, whether it’s a teammate or coach you’re looking to join. T.R. Doty was just another Canadian kid playing college ball south of the border when he found himself playing in the little-known Swedish professional baseball league.

“The opportunity to play in Sweden came up because when I went to Santa Barbara City College I met someone from Sweden who plays baseball as well,” he says. “We had kept in touch over the years and I knew that he played in the professional league there and was very interested. He got me in contact with his coaches and I ended up taking the opportunity to go there.”

On-field differences

Wherever you go four balls is a walk to first and three strikes is a walk back to the dugout, but that doesn’t mean the sport is stylistically uniform around the globe.

The on-field differences are significant and the reasons behind them can range from strategic philosophy, to talent level, to different standards for foreigners and even outright corruption.

In Japan, for instance, offence is not driven by the home run or big inning nearly as much as it is in the majors.

“In Japan you play for one run, everything is geared for scoring one run at a time,” Mathieson explains. “If the leadoff hitter gets a single the second guy is bunting him over, which you’d never see in the States.”

Another issue Canadians — like all foreigners — face in Japan is a strike zone that’s far friendlier to the natives, and pitchers that are inclined to pitch them differently.

“The strike zone was a little bit warped and I felt like the way the pitchers pitched to us as import players was a lot different than how they pitched to Japanese players,” Ducey says of his time with the Nippon Ham Fightrers. “There was a little extra on that fastball.”

Aaron Guiel, who spent five seasons in Japan from 2007-11 after a five-year MLB career, encountered that different treatment and saw it affect a home run title chase in 2007.

“My first year there I was in the running for the HR title and I heard rumours, ‘Watch out they don’t want you to win.’ Sometimes even your own teammates don’t want you to win, they want the title to go to a Japanese player,” he recalls. “So I did notice that near the end we’d play opposing teams and they’d throw strikes to the other Japanese guy in the running against me and they wouldn’t throw strikes to me — so it became pretty evident.”

Guiel also spent some time in the Mexican League where he found another game he didn’t quite recognize.

“You see a lot of curveballs, you see a lot of pitching backward, you see a lot of trickery and bunting,” he says. “Things like that. It’s not as dynamic a game as it is in the U.S., but it’s a fun creative game.”

In Doty’s unusual Swedish odyssey, it’s a cross-generational player pool that gives the game a different look.

“The age ranges quite a bit. There will be sometimes more younger players on one team, and then another will have more older and experienced player. The ages ranged from 17 to 45.”

Not all the variations are that benign, however. Toronto native and minor-league veteran Todd Betts was faced with some scary corruption during his tour in Taiwan in 2006.

“The teams had in-house talks about what’s been going on and how to stay away from it,” he says. “We knew about it. I was being approached about throwing games, things like that, you just say, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about’ and get away.”

Baseball is baseball in theory, but things are always a little different in practice.

The atmosphere

As far as global standards go, Canadian and American baseball fans are downright tame.

Betts played 14 years of professional baseball and he never saw anything like the atmosphere he witnessed in Taiwan when spent a year there in with the La New Bears in 2006.

“A Blue Jays game is boring. They play the music. The guy walks up to the plate, people talk amongst themselves. In Taiwan we’re talking cheerleaders, fireworks and songs that play throughout the game. It’s three-and-a-half hours of non-stop music. When they introduce the player hitting they play the song through the whole at-bat. It’s a production, it’s something to see.”

Former Blue Jays starter Scott Richmond pitched for the EDA Rhinos in Taiwan in 2016 where he became a viral sensation with this catch.

Much like Guiel, he found himself impressed with the fans in Taiwan.

“The fans are really passionate about their team and individual players which is quite common in Asian baseball,” he says. “Loud singing, chants, music and instruments going at all times makes it interesting for everyone there.”

Across Asia there is a reputation for more rabid fans.

“Each team has cheerleaders and a fan section that will follow the team on the road,” says Scott Diamond, the former Blue Jays southpaw who plays with Romak in Korea. “They help sing the introduction and fighting songs from start to finish.”

“Fans will approach you at the field or around town and give you gifts,” Romak says. “They expect a lot of foreign players but they’re really nice.”

In Japan, Ducey found fans supported him individually.

“They showed up every night and they brought banners to fly in outfield. The Canadian flag flew when I was hitting.”

More boisterous fanbases are not unique to Asia, though. When playing in the Philadelphia Phillies system Tyson Gillies found himself in the Venezuelan Winter League, where he saw fans at the next level of rowdiness.

“The noise down in Venezuela was like nothing I’ve ever heard before. I’ve been to MLB playoff games and the liveliness of the crowd just doesn’t compare,” he says. “I remember playing a game against one of my friends and he got a cherry bomb thrown at him on the field.”

Off-field life

Adjusting to a different style of baseball and a language barrier is one thing, making yourself at home on another continent is something altogether different.

Most leagues outside of North America put a hard cap on foreign players, meaning the ex-pat friend pool is pretty shallow.

“[From 1995-97] there was only three foreign players on the team,” Ducey says of the Japanese rules. “And we rarely saw one who was a starting pitcher on his own program. So it was really myself and one other position player.”

Luckily for the MLB journeyman, he had his wife and children to keep him company.

“The food was tremendous and the living accommodations were phenomenal. Had zero issues off the field. I truly enjoyed it. My wife loved it over there. My kids loved it over there.”

For those without families the experience can be a little more challenging.

Romak certainly had his lonely times in Japan.

“I had some moments in Japan were I felt pretty isolated. There are a lot of little things you take for granted when you can interact with people. Body language is everything, and something I have to be cognizant of because intensity, passion, frustration are all things that can be taken as disrespectful.”

Guiel also felt like he was on a bit of an island while he was in Mexico.

“‘There was not a lot going on for me off the field,” he says. “I was the only English-speaking player on the team, in southern Mexico, and didn’t speak the language. So it was a tough experience mentally because you didn’t have anyone to relate to.”

Gillies found he had his off-field experience limited as well, but more by the political situation in Venezuela than anything else.

“While I was playing the election was going on and it was a very dangerous time to be around. Besides baseball we basically stayed put in the gated hotel community.”

One thing that players heading thousands of kilometres from home often dread is dealing with a new cuisine. As it turns out that’s almost never a problem.

Whether it’s befriending a fellow Canadian who owns a restaurant like Betts did in Taiwan, getting into Korean BBQ like Romak, or going all in on Japanese cuisine, hunger is not a worry. Japan especially tends to get rave reviews in that area.

“Food-wise they don’t use preservatives or anything like that in the food. There’s lots of fresh stuff and [me and wife] really changed. I haven’t had fast food in five years now,” Mathieson says. “If you like pasta there are more Italian-certified chefs in Japan than there are in Italy. If you like steak there’s Ohmi beef and Kobe beef. There’s every kind of food in the world you can think of — but with a little Japanese kick to it.”

Missing home

To a man, friends and family are the things overseas ballplayers miss most, but there are other pieces of Canada they find themselves yearning for.

“I would say driving,” Mathieson says. “I drive in Japan, but it’s a stressful a drive over there. I like the open roads.”

Ducey concurs.

“No question: Driving.”

Romak just misses the safe sensation of touching down at home.

“Both Japan and Korea are incredibly safe countries, but I always get a feeling of security when I land back in Canada.”

For Diamond, it’s a classic.

“I really missed my mum’s cookies and baked goods,” he says. “Luckily she knew this and shipped out a box filled with them.”

Gillies perhaps had the most Canadian answer of all, speaking for Canucks around the world who find themselves away from home.

“Poutine has to be pretty up there…”

More MLB coverage on Yahoo Canada Sports: