How the 18-49 Demo Defied Death—and Became TV’s $79B Currency

Between 2018 and 2022, David Zaslav’s compensation package was a smidge under a half-billion dollars ($498.9 million), making him the world’s highest-paid media executive. As the CEO of Warner Bros. Discovery, Zaslav steers an enterprise that boasts the largest primetime viewing share of any television operation, and the combined networks in his portfolio average north of 100 million viewers per week. And while he’s refashioned himself as an old-school movie mogul, it’s safe to assume that the WBD boss watches a fair amount of TV.

Given all that, Zaslav would seem to be an ideal target for advertisers looking to connect with affluent and engaged viewers. But because marketers remain in thrall to the laughably artificial construct that is the target demographic (adults 18-49), the 63-year-old Zaslav effectively does not exist. To advertisers, the guy who lives and breathes TV and whose net worth exceeds the GDP of Micronesia is as inessential as a phantom.

More from Sportico.com

Eagles-Chiefs' 29M Viewers Crushes MNF TV Record in the ESPN Era

MSG Implements AI for Knicks, Rangers Highlights on Social Accounts

According to the arbitrary dictates that render any viewer who hits the 50-candles mark as inconsequential as vapor, not only is the head of America’s most-watched TV conglomerate a virtual non-entity, but so is the executive who leads WBD’s ad sales team. In fact, none of the heads of the network sales groups is demographically viable, which is to say that the marketers who spend upwards of $78.7 billion a year on TV inventory aren’t terribly interested in reaching the people who sell those ads to them. If you’re beginning to suspect that all of this is about as dumb and pointless as sticking your head inside the Large Hadron Collider, you may be onto something.

The practice of selling demos is predicated on tortured logic—young people are hard to reach, therefore they must be a more valuable resource—and a wheezy set of assumptions about brand loyalty that has never been elevated from the realm of the hypothetical. That the 18-49 demo was more or less plucked out of thin air 60 years ago only serves to underscore the capriciousness of the entire enterprise.

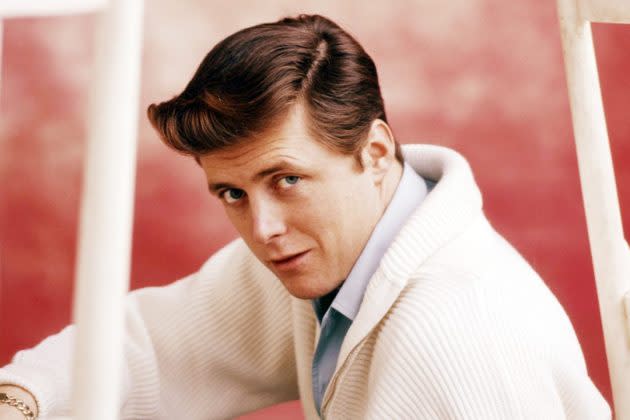

Here’s how the demo hustle went down. In the early 1960s, ABC was struggling to compete with its affiliate-rich, more established rivals CBS and NBC. After watching a throng of Philadelphia bobby soxers losing their goddamn minds as Johnny Mathis or Troy Donahue or whoever crooned affably on American Bandstand, ABC president Oliver Treyz had an epiphany. Rather than try to go toe-to-toe with the heavyweights, ABC would instead punch above its weight by pitching advertisers on its disproportionate popularity among younger viewers.

At the time, Nielsen did not measure discrete audience segments, so when Treyz and ABC founder Leonard Goldenson first approached the company with a request to blow up the standard household ratings by which everyone kept score, all parties concerned were heading out into the “Here Be Dragons” area of the map. ABC’s proposal was wildly ambitious and, as it turned out, just as impractical. Because auto manufacturers accounted for the majority of its sales, the network hoped to assign a demographic sliver to the models most likely to appeal to that particular age range. In other words, it would sell its audience of men 18-24 to Corvette, while the older end of the spectrum, breadwinners in their early to mid-30s, would be pinned to Buick and Cadillac.

Unfortunately for the car companies and the legions of hot-rod enthusiasts who tuned in every Friday night for 77 Sunset Strip, the proposal wilted in the face of the era’s technological limitations. Nielsen had only been measuring TV audiences for about a decade when Treyz and Goldenson came calling, and contemporary punch-card computers boasted all the processing power of a fluffernutter sandwich. An entire baseball team could fit comfortably inside a Galaxie 500, provided you shoved the right side of the infield in the trunk, but Space Age data processing was far too primitive to match potential Ford buyers with 25-to-30-year-old fans of ABC’s Major League Baseball Game of the Week.

The compromise: a wildly inclusive chunk of the audience that kicked in at age 18 and terminated right before the half-century mark. And we’ve been stuck with it ever since.

Now, as much as ABC’s reach seems to have exceeded its grasp, the setback didn’t prevent the network from turning the TV ad business on its ear. In 1962, in a bid to align its programming slate with the automakers’ fall release schedule, ABC set all of its new series’ premieres to air in a single week in September, thereby ushering in the modern broadcast season … which in turn gave rise to the spring upfront bazaar. Five years later, ABC became the first network to offer performance guarantees to its advertisers. (If Oliver Treyz hadn’t bore such an uncanny resemblance to Jimmy Hoffa, there’d probably be a statue of him standing somewhere on Madison Avenue.)

Long story short-ish: ABC essentially fabricated a demo out of whole cloth to steal share from its more widely distributed competitors. To this day, that arbitrary age group remains the coin of the realm for a marketplace that no more resembles the ‘60s TV landscape than Dick Clark’s weekly musical showcase resembles our current pop music environment—although it’s admittedly a lot of fun to imagine the looks on the faces of the so-clean-they-squeaked-like-a-vigorously-rubbed-balloon Bandstand teens if they’d ever been confronted with the spectacle of Nicki Minaj lip-synching “Anaconda.”

While networks are now able to slice and dice their audiences into ever-more-discrete segments, 18-49 is still the metric that commands the bulk of the ad dollars. A decade after ABC shelved its auto-targeting ambitions, advertisers had become increasingly adept at reaching more concentrated fragments of the vast TV-watching horde, and media agencies began tailoring their clients’ messaging to strike an acquisitive chord in the hearts of their prioritized viewers. One campaign was so successful that it became the subject of macabre fascination for a generation of young TV fiends.

Featuring an intractably finicky 4-year-old named Mikey, the infamous Life cereal commercial remained in circulation for the entirety of the Me Decade. By the time the rumor about the exploding kid hit our elementary school—the tiny pitchman was said to have met his maker after chasing a bag of Pop Rocks with a can of Coke—the deathless ad had helped Quaker Oats grow Life into one of the top-selling cereal brands in the U.S.

Despite the fact that CB radio was the closest thing there was to a public Internet, every kid in America knew about the goofy myth of Dead Mikey, and more than a few of us tried to replicate his doomed experiment. (Shoutout to Mrs. Gallagher for her role in preventing a whole Jonestown in Garanimals situation out by the tetherball courts.) As it happens, Mikey made a few hundred more commercials before he grew up and started selling them. Mikey’s real name is John Gilchrist, and he’s served as the director of media sales at MSG Networks for the last 12 years. While Mikey is very much alive and well, he’s basically in the same boat as David Zaslav; having celebrated his 55th birthday this year, Gilchrist has passed through the demographic event horizon. Mikey didn’t take the Big Dirt Nap back in the ‘70s, but as far as most advertisers are concerned, one of TV’s most effective pitchmen, and a current New York sports sales maestro, may as well have met his fizzy end the moment he turned 50.

After all this time, demos are still as phony as the chemicals that give Pop Rocks their otherworldly flavor. It’s a wonder that marketers haven’t learned to spit them out.

Best of Sportico.com