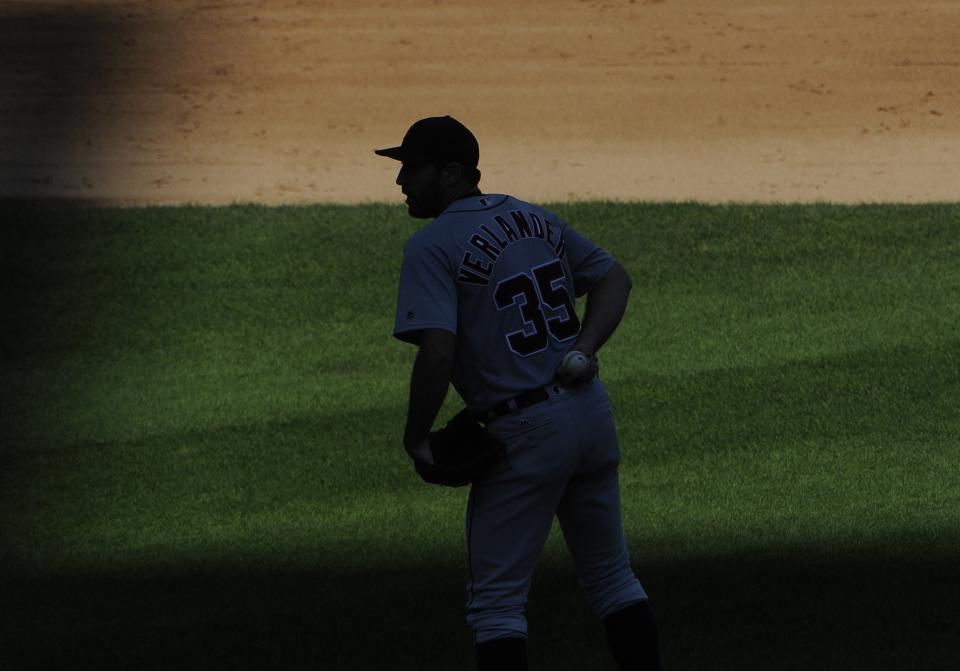

The rebirth of Justin Verlander

Every pitch hurt. It got so bad that Justin Verlander, voracious competitor, uncompromising red ass, one of the great pitchers of his generation, started rooting for quick innings. Not when he was throwing. When his Detroit Tigers teammates were at the plate. This pained him to no end, but then so did his arm, and the easiest way to keep it from locking up in 2014 was to get back on the mound, and when the Tigers put up three or four or five runs, Verlander could feel his arm in full revolt.

“I was throwing balls in the cage just trying to keep my arm loose. It was miserable,” he said. “It’s funny. A lot of people say when you turn 30 everything changes. You turn 30 and everything starts hurting, and right around that time is when things started hurting. That year I threw 200 innings, and not one of them felt good. Not one pitch felt good. Everything hurt. Specifically my shoulder. I’d find myself thinking – that’s the first time in my career where I looked at the end and said, ‘[Expletive], man, if this is what it’s going to feel like the rest of my career, this isn’t fun.’ And it wasn’t fun. That scared me.”

It’s two years later, so Justin Verlander is sanguine about his lowest moments, about how they made him a better pitcher and a better person and delivered him to where he is today: back. Back to his dominant self, striking out American League hitters at a higher rate than he did during his MVP season and allowing the fewest baserunners per inning in the league and launching himself back into the Cy Young conversation and propelling the Tigers on another run at the postseason. This is where the 33-year-old Verlander feels like he belongs, where he worked so hard to get, even if he wasn’t sure he’d make it there.

Injuries tinker with every athlete’s psyche; they particularly punish those like Verlander, whose attention to detail and introspection make for a potent ally when all is well and a nemesis otherwise. Verlander’s issues started in 2013 when the mechanics upon which he so relied started failing him. A torn abdominal muscle set off a chain reaction of tiny changes elsewhere, almost imperceptible to the common eye but abundantly clear to Verlander. No matter how much he tried to revert to his old self, Verlander’s body wouldn’t allow it, and never did he declare himself hurt enough to stop throwing, not with the $180 million contract and the expectation that he eat up innings as he had ever since his arrival in 2005.

So he pitched, and he pitched well below his standard. Surgery on his abs in the offseason before 2014 set him on the proper path, though it took far longer to find himself. “With core surgery, I was a brick,” he said. “Nothing worked independently. My legs and core were like a tight attachment instead of being able to rotate. Everything I’d been doing wrong took a toll on my body that I needed to solve.”

Verlander spent 2014 searching. His posture was failing him. The core issues had caused his torso to tilt back too far during the delivery, and his arm, he said, “lagged behind” on account of that. Indirectly, the abdominal issues begat pain in his shoulder. Verlander’s velocity cratered. He couldn’t attack hitters with his typical aplomb. His ERA ballooned to 4.54 and his strikeout rate dipped to the lowest since his rookie season. He allowed the most earned runs in the AL.

“Imagine trying to throw a good curveball or slider when you’re going up and over. It’s almost impossible,” he said. “Because of the mechanical flaws I had going on, all of my off-speed stuff wasn’t nearly as crisp, either. Everything was loose, hittable. Nothing was good. But I was out there pitching.”

This is something in which Verlander takes pride, and understandably so. He still managed to exceed 200 innings in 2014, his eighth consecutive season doing so. Only James Shields and Mark Buehrle reached the 200-inning plateau every year over the same stretch. Still, Verlander loathed the notion of backsliding into an innings Pac-Man. He believed dominance remained in his arm. It was simply a matter of harnessing it.

Verlander would type his name into a Google search box, click the Images tab, look at pictures of himself and peg, with 100 percent accuracy, whether the photographs were taken during his best years or in 2013 or ’14. He knew what he needed to look like at every point in his delivery and was determined to rid himself of the imperfections. He worked with physical therapist Annie Gow in New York during the offseason and hit spring training in 2015 fully recovered and ready to see whether his optimism was warranted.

In his last start that spring against Toronto, Verlander brimmed with confidence. His stuff felt crisp. Even better, the pain was gone. Then pain shot through his triceps area. Verlander didn’t panic. The injury actually was an issue with his latissimus dorsi – the muscle commonly known as the lat, which connects to the triceps muscle – and he believed that with time to heal, it wouldn’t derail his progress.

Verlander returned last season for 20 starts. His velocity crept back. This spring it jumped another half mile per hour, to an average of 93.3, not where he once was but harder than any of the baker’s dozen 33-and-older starters. The speed of Verlander’s fastball doesn’t tell its whole story, either. Hitters always have talked about how it almost jumps or rises as it approaches the plate, an optical illusion that stems from the rapid spin Verlander generates. No starter’s fastball generates the RPMs of Verlander’s, and the additional velocity weaponizes it that much more. On top of that, Verlander started to throw his slider harder, worried that hitters no longer had trouble differentiating it from his curveball, and it has turned into perhaps his best pitch.

And here he is, less than a month left in the season, ready to cross the 200-inning mark in his next start Sunday, at 209 strikeouts, with a 3.28 ERA and the old feeling back.

“All of a sudden, it becomes fun again,” Verlander said. “I was allowed to compete with the other team as opposed to competing against myself. It’s hard enough to compete with the best players in the world when you feel good. I quickly realized when you’re not feeling good and competing against yourself and them, it’s not a good recipe for success.”

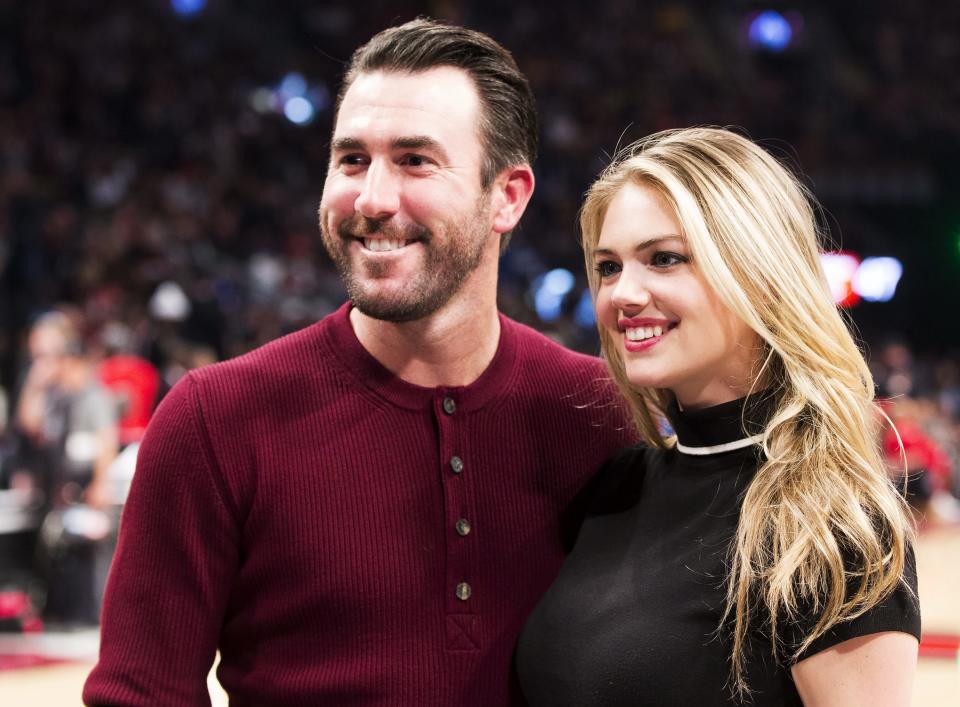

There’s a peace in that, and everywhere in Verlander’s life these days. “I’m in a good place, on and off the field,” he said. Verlander and supermodel Kate Upton got engaged earlier this year, and he has adjusted to the life of celebrity outside of Michigan. He does relish the time in 2014 when he and Upton were traveling to Slovenia and a woman approached the couple and said: “Excuse me, excuse me … Mr. Verlander?”

“I looked at Kate and went, ‘Ha!’ ” Verlander said. “And then I said, ‘Hey, how are ya!’ ”

There are the moments, of course, that make it difficult. Verlander’s personal photos were hacked and posted on the Internet in 2014. Rarely does he go out without someone snapping a photograph, whether using a telephoto lens or a phone camera.

“Being a celebrity in general, you lose privacy,” Verlander said. “There’s a societal problem right now with celebrities not having privacy, and the way the laws are written, it protects other people, not celebrities. The laws were written before the world turned into what it is now with social media and everyone being a paparazzi. It’ll be changed, I think.

“There just need to be more rights for celebrities. And I know that could come across as ‘Wah, wah, wah, here’s another celebrity crying.’ But if anyone can imagine their whole personal life being exposed or never having the ability to just be comfortable in public, that’s tough.”

He understands the tradeoff. Verlander is a pragmatist, a quality that helped him through the lows of 2013 and ’14. Those are just memories now, residue of injuries past, and he works hard as ever to prevent others from cropping up. Verlander can do only so much. He gets that. Until then, he’ll keep tweaking and iterating and ensuring his body does what he needs it to. He’s seen what happens when it doesn’t. The only quick innings he wants to root for are his own.

More MLB coverage on Yahoo Sports: