Why NFL's rookie salary cap could lead to dearth of quality QBs

Five years ago, the NFL waged a public-relations campaign in favor of establishing a rookie salary scale. Commissioner Roger Goodell beat the drum for popular change that would eliminate training camp holdouts and massive first contracts such as Sam Bradford's, which in 2010 guaranteed the quarterback $50 million before ever taking a snap.

Either ignored or misunderstood, however, was the predictable byproduct of a salary structure, one the NBA saw happen when it implemented its own in the mid-1990s. By weakening the financial incentive of staying in school in order to climb in the NFL draft and get significantly more money the next year, perhaps even Bradford money, prospects would instead leave college as soon as possible, in part to get the clock ticking to eventual free agency, where the real cash awaited.

The NFL draft was certain to be awash in more and more young players.

"I don't agree with that [assessment]," Goodell told Yahoo Sports in 2009, strangely dismissing the NBA example. "I think it's the opposite. If there's not big money to come out, you stay in school, improve yourself and then play in the league for a long time."

Goodell was completely wrong. The power of money was right again.

In 2010, the year before Goodell's salary scale was implemented, 53 players with college eligibility remaining entered the draft.

Just four years later, in 2014, the number had nearly doubled to a record 98.

College bowl season kicks off Saturday and with it comes a projected stream of underclassmen declaring for the draft. The NFL is looking on nervously, wary that another record number of college juniors, less prepared than their predecessors, will arrive at its doorstep, the result of a problem of its own creation.

A player must be three years removed from high school to be eligible for the draft. The NFL wants players, especially quarterbacks, to play all four seasons of college ball, preferably with an additional redshirt year, to allow maximum physical, mental and emotional development.

The salary scale, however, meant the difference between being the No. 2 or No. 28 pick wasn't now perceived to be great enough monetarily to come back and try for it. That's even more true for a fourth-rounder wondering if another year of development could get him to the second or even first round.

As such, players began to leave college at the first chance.

It's exactly what happened to the NBA after it installed its own salary scale for rookies. The flood of younger and younger players was so significant the draft went from mostly college juniors and seniors to plenty of high school kids. The average years spent in the NCAA for first-round NBA selections went from 3.3 in 1994 to 2.0 in 2004.

The NBA was forced to enact an age limit to stem the tide, but it's never recovered from the trend. A decade later it's still dealing with the issue and proposing an additional increase in the age limit.

The NFL has now grown so concerned about the trend it enacted a new plan this year that both limit the amount of information it provides underclassmen seeking input on their draft potential and the number of players who can receive it.

Only five underclassmen per college program can receive info and the NFL will only tell them they are likely first- or second-round picks. The league used to categorize players into each of the first three rounds, or declare them likely to be drafted or undrafted. Anyone who asked would receive an evaluation.

The NFL's hope is ignorance breeds fear and apprehension, causing a kid to just stay in school.

Agents scoff at the idea, noting the less information available, the easier it is for the unscrupulous to tell a prospect he's a third-rounder even if he isn't. Besides, the wheels of capitalism are impossible to stop and as long as the salary system is in place, the movement will grow. Privately, most are predicting another record year of declarations, with the number jumping above 100.

On an average year, there are only about 254 draft slots (the number of compensatory picks vary). This is becoming a huge issue for the league.

"Hearing the number of junior entrants this year will dwarf [the old record]," one agent told Yahoo! Sports.

For all of Goodell's missteps on discipline and public relations, his regime's failure to study, or to simply reject, the NBAs experience is a far more acute problem for the league.

The rookie salary scale isn't without positives, of course. It limited the financial risk of drafting a bust, eliminated energy-sapping contract battles and allowed teams to get young talent at a bargain rate, locked up fairly cheap for up to five years (plus the option to franchise tag them for three more).

The number of underclassmen, however, is a concern, especially at the quarterback position where historically additional game experience, age and maturity are seen as a major positive. Of the current top 20 quarterbacks in passing yards this season, 14 exhausted their college eligibility. Three (Andrew Luck, Ben Roethlisberger and Joe Flacco) of the other six spent four or more years on campus due to redshirt and transfer rules.

This year's crop of first-round rookie quarterbacks – Blake Bortles, Johnny Manziel and Teddy Bridgewater – all left with at least one season of eligibility remaining (Manziel had two). None of them made a significant impact on the league this year.

The current top 20 NFL quarterbacks played an average of 3.7 seasons of college football and spent an average of 4.2 years on campus. They averaged 36.4 college starts. Manziel, in contrast, spent only three years at Texas A&M, just two of them active, where he started 25 games.

The best rookie quarterback, perhaps coincidentally, was Oakland's Derek Carr, a second-round selection. He put in five-plus years at Fresno State, playing four seasons and recording 39 starts.

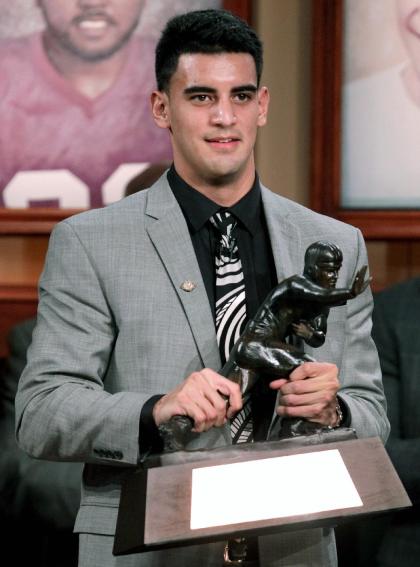

The two most hyped quarterback prospects for the 2015 draft, Oregon's Marcus Mariota and Florida State's Jameis Winston, have eligibility remaining (Winston has two seasons left). The lack of experience, NFL execs say, is compounded when a quarterback plays in a spread, rather than pro-style, offense.

Once a trend like this begins, it grows like a rogue wave.

With each successive year of additional players leaving college football there is a vacuum left behind that younger and less able players then fill. That means younger and younger players become starters, stars and even Heisman winners (Manziel and Winston were the first two redshirt freshman to ever win the award). Then there is less competition for top draft slots, which requires risk-taking on unfinished talent, especially at quarterback.

Forty-five of last year's 98 entrees weren't even drafted, although many found their way on rosters anyway. Had those good players stayed in school and improved, then 45 younger players would have found the college competition tougher and not seen such an open path to this year's draft.

There is more than one reason more players are leaving early. An understanding of the health issues associated with the game – why risk brain trauma for just tuition, room and board? – and an increased opposition to the NCAA amateur model also play a role.

Still, money remains the most powerful behavioral influence in American society. You'd think the NFL -- of all entities -- would understand that.

In 2010, St. Louis and No. 1 overall selection Sam Bradford agreed to a six-year contract with $50 million guaranteed. That's an average, in inflation-adjusted numbers, of $9.03 million per year.

In 2014, Houston and No. 1 overall pick Jadeveon Clowney agreed to a four-year deal with $22.3 million guaranteed, or $5.56 million per year.

In overall money, Bradford ($54.2 million in inflation adjusted) was guaranteed nearly 2 1/2 more. Perhaps more important, however, is the difference between being the top selection overall and a late first-rounder who might have otherwise considered returning to school and moving up, thus gaining that extra year the NFL covets.

In 2010, the last pick of the first round, Patrick Robinson, signed a five-year deal worth $6.085 million guaranteed, about $44 million less than Bradford. The last first-round pick of 2014, Bridgewater, received an annual salary of $1.4 million, meaning Clowney made about four times more.

The salary scale gets even flatter in the later rounds, both paying those rookies less overall while decreasing the reason to come back to school.

Late-round picks are making around $600,000 per year, very nice money for a desk job but hardly NFL riches many envision, especially with the health risks involved. The goal now is reaching free agency while you may still be young enough to be worth something that can set a family up.

"The team that drafts you [in the first round] can keep you locked up for five years," agent C.J. LaBoy of Relativity Sports said. "Then you're 27 or 28 and you're literally near the tail end of you career by the time you get to your second contract. If you get to a second contract."

Better to get in at 20 or 21.

And for picks in Rounds 2 through 7, you can actually reach free agency a year sooner, which provides an odd benefit to not move up.

The collective bargaining agreement is set until 2021, which means the core problem isn't easily fixed. Whether a generation of quarterbacks can overcome this remains to be seen.

The NFL is hoping less information will stem the tide. Time will tell if that bizarre concept will work, but Roger Goodell was dead wrong on the ramifications surrounding a salary structure before.

Now he and his league are scrambling as a result.