Meet the banker behind the biggest deal of 2016

Fresh out of college, Michael Kramer began his career at one of Wall Street’s most highly regarded boutique banks, Houlihan Lokey, as a data-entry clerk. By the time he reached his mid-20s he was a partner at that firm. Currently, he leads one of the newest boutique investment banking firms that’s making waves in mergers-and-acquisitions (M&A) and restructuring.

At just over one year old, Kramer’s Ducera Partners LLC — a name derived from the Latin verb dūcere, meaning “to lead, to guide” — currently ranks No. 21 on the global M&A league tables, No. 17 in the US, and No. 3 for boutique banks worldwide, according to data compiled by Dealogic.

The upstart bank landed 2016’s biggest deal, advising agricultural giant Monsanto (MON) in connection with an unsolicited takeover bid from German drug-and-chemicals-maker, Bayer (BAYRY). On Wednesday, Monsanto said yes to Bayer’s $66 billion offer, making it the largest agribusiness deal on record. Approximately $100 to $110 million in fees are expected to be divvied up between lead adviser Ducera and Morgan Stanley for their sell-side advisory roles, according to estimates by consultant Freeman & Co.

That’s an impressive deal for any M&A shop. But Ducera’s bread-and-butter business is restructuring, making the Monsanto assignment all the more impressive. In the past 12 months, restructuring deals the firm has worked include Puerto Rico’s Government Development Bank, rig operator Hercules Offshore, NewPage Holdings, Sun Edison, and Claire Stores, just to name a few.

Kramer’s relationship with Monsanto began years ago

It’s not Kramer’s first time advising Monsanto. Over a decade ago, Kramer and his team made their own unsolicited offer to Monsanto — they put together a pitchbook, mailed it to the chief financial officer of the company and followed up with a cold call. The company’s treasurer returned Kramer’s call and invited the team in for a meeting. They ended up advising Monsanto in the 2003 restructuring of chemical company Solutia.

One thing to know about Ducera is that it’s a real team effort. In addition to Kramer, the bank has six partners — Derron Slonecker, Bradley Meyer, Joshua Scherer, Agnes Tang, David Skatoff, and Adam Verost. What’s remarkable is that their relationship spans two decades, with the core group having worked together at various firms since their early days at Houlihan Lokey.

“We grew up together and we stayed together. I get the accolades for our success because I’m the head of the group, but I couldn’t do it without my partners,” Kramer told Yahoo Finance in his first-ever interview.

“An overnight success that’s been 20 year in the making”

Not only is their long-term relationship a testament to their cohesion and loyalty, but it’s also been integral to their success.

“Ducera is an overnight success that’s been 20 years in the making,” said attorney Evan Flaschen, one of the world’s leading global financial restructuring experts.

“It’s their names that matter, not the name on the door,” Flaschen added. “People will hire Mike, Derron, and their team wherever they go.”

Anthony Scaramucci, the founder SkyBridge Capital and host of “Wall Street Week,” described Kramer as a “unique banker.”

“He is an entrepreneurial executive, his clients know that he could do their jobs which gives them great confidence in his advice and judgment,” Scaramucci said.

Like many who have long careers on Wall Street, there have been some bumps in the road along the way. Perella Weinberg Partners – the boutique bank cofounded by Joseph Perella and Peter Weinberg – is currently suing Kramer, Slonecker, Verost and Scherer in what has become a hotly contested lawsuit attracting the attention of the press and C-suite level Wall Street executives.

But even in the midst of this lawsuit, Perella Weinberg described Kramer in court papers as a “talented” and “productive partner,” noting the firm “valued his contributions.” All of Ducera’s partners, except David Skatoff, worked for Perella Weinberg.

Yahoo Finance recently met with Kramer and Slonecker at the bank’s midtown Manhattan office overlooking Park Avenue. Kramer is intellectually commanding but also down-to-earth. It’s clear that he’s fiercely loyal to his people, and a culture of teamwork and hard work permeate the firm.

Not your typical Wall Street rainmaker

Kramer, who is 47 and proudly sports a flat-top haircut (he’s “trying to bring the style back”), certainly breaks the mold of Wall Street. He doesn’t come from a family with a Wall Street lineage, nor does he have an Ivy League degree hanging in his office. In fact, he hardly ever uses his office. Instead, Kramer and the partners sit right next to the junior associates and analysts in a trading floor-style setup.

One consistent theme in any conversation with Kramer’s clients and colleagues is his ability to craft and execute effective solutions. People who’ve worked with him have described him as a “creative dealmaker” and “problem solver.” Another former colleague added that he’s an astute listener and observer. A top global restructuring lawyer has commented that Kramer is likely the most innovative dealmaker he has seen on Wall Street.

“He has a good ability to hear a tremendous amount of information and synthesize it down to key salient points. And that is a skill. It’s a real skill.”

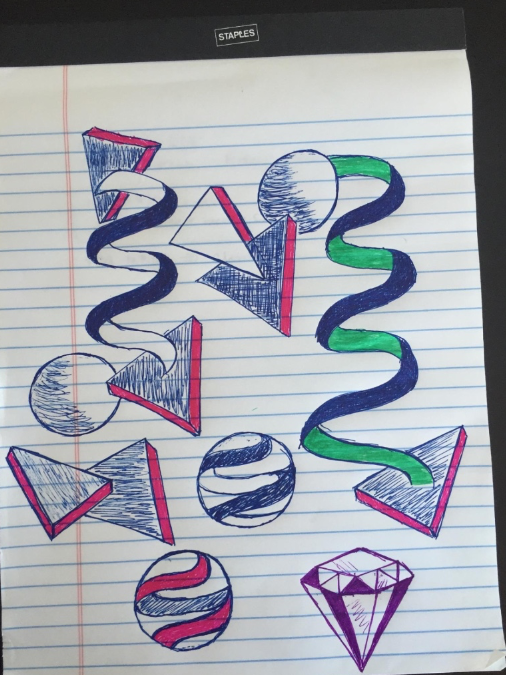

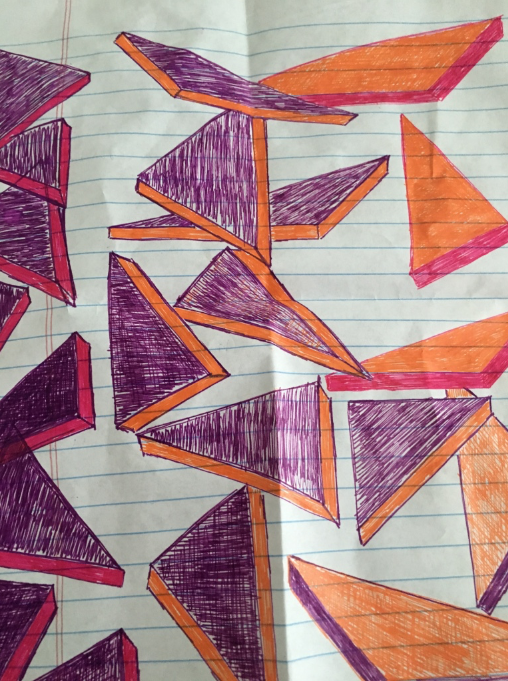

His creativity expands beyond deal making – he’s a prolific doodler, too. Throughout the conversation with Yahoo Finance, he sketched out intricate geometric figures on a legal pad in purple, pink, green, orange, and blue ink.

“I’m a doodler,” he confessed. “People historically have scoffed about it, complaining ‘You don’t pay attention, sitting there doodling. You seem uninterested.”

But he’s listening intently, and he doesn’t miss a beat.

“Doodle and give the right advice and business perspective,” Slonecker added.

Beyond the workplace, a married father of three, Kramer resides in a stunning home in Connecticut that he helped design from top to bottom. There, he helps his wife Tina and other volunteers pack backpacks of food for more than 450 needy kids during the school year and nearly 800 children in the summer who receive weekend meals from a not-for-profit that his wife cofounded with her partner Shawnee Knight, Filling In The Blanks. An entire house on the Kramers’ property is dedicated solely and exclusively to the work of Filling In The Blanks.

“Mike’s been there since the beginning, helping in every way, starting with picking up the food itself. On packing day, he’s up there unloading the truck, carrying bins around. He’s figured out various systems to maximize the efficiency of our work, focusing on every detail of our operations,” Tina Kramer said. “Since it’s very grassroots, he’s always trying to think of new ways to fill every square inch.”

From blue-collar LA to white-collar Wall Street

Kramer is living the American dream. He comes from modest beginnings and his career has seen a meteoric rise.

An Hispanic-American, he grew up in a middle class household in Los Angeles. His mother was a probation officer at a juvenile male correctional facility. “Growing up, there wasn’t much I could do that my mother hadn’t seen or dealt with,” he said.

He attended nearby California State University, Northridge — the same school that both his parents attended. In college, he studied finance. He wanted to work on Wall Street, but the school wasn’t then exactly a hotbed for investment banking recruiting.

Toward the end of his junior year, Houlihan Lokey advertised on campus for a data entry internship. Kramer got the job.

‘He’s just outworked everybody’

During the summer of 1989, he combed through boxes of financial statements, pulled out the relevant contact information, and put it in Houlihan Lokey’s system. He breezed through what was expected to be a time-consuming task.

“He did more work than all the other people put together,” said one former colleague. “That’s just been Mike his whole career — he’s just outworked everybody.”

He continued the internship during his senior year of college. After graduating in the spring of 1990, he joined Houlihan Lokey full-time. He was only 20 years old.

As part of the analyst program, the various group heads came through and spoke to the class about the work their respective divisions were doing. That’s when Kramer encountered a charismatic and electrifying former bankruptcy attorney turned banker named Jeff Werbalowsky. At the time, Werbalowsky was the co-head of the restructuring group alongside Irwin Gold, another recovering lawyer that turned to banking.

Werbalowsky came off as brilliant and articulate, and Kramer immediately wanted to work for him. “I said, ‘That’s exactly what I want to do.’”

For his part, Slonecker recalled “a mix of exhilaration and fear when you listened to [Werbalowsky].” He added: “It hits you like, ‘I really want to do this, but do I have what it takes?’”

“C-. Try English next time.”

It took some persistence on Kramer’s part to convince Werbalowsky and Gold to give him a shot. He was turned down multiple times. Kramer persisted in his efforts and they finally relented, assigning him a small project. Kramer finally made the cut.

Former colleagues say he showed up at the right place at the right time — and with the right attitude.

At the time, restructuring was in its infancy. It was the real entrepreneurial business. But it wasn’t long before Houlihan Lokey’s restructuring business skyrocketed. Today, they’re widely considered one of the premiere firms in the area of restructuring.

At the onset, just a few young analysts worked on the team, working side-to-side with Werbalowsky and Gold, sometimes until 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. preparing just to get invited to a pitch.

There wasn’t a sense of entitlement to win. It was intense, ambitious, and entrepreneurial.

“The best people in the firm wanted to be part of the restructuring team,” said Slonecker, who, like Kramer, took a nontraditional path to break into the ranks of Wall Street.

Slonecker, 48, started in a different business inside Houlihan and joined the restructuring group in 1994.

He added: “It was hard and intense, and that attracted the hardest working people in the firm. With every deal that we pitched or brought into the firm, we raised the bar and brought out the best in ourselves and our colleagues.”

Werbalowsky expected the best of all his employees. Even to this day, Kramer keeps the reviews from his former boss, which Kramer notes, “could be pretty pointed and rough.”

“One year Jeff said that I was a horrible writer. I’d write a memo for him and he would mark it up with the dreaded red pen and write, ‘C-, Try English next time.”

Lawyers, naturally, place a premium on strong writing skills. Determined, Kramer came back the next year bringing stronger writing skills. His bosses, of course, highlighted another area where he needed to improve. They constantly pushed Kramer and the others to get better year after year.

“To borrow a sports analogy, good coaches don’t tell their talented players how great they are — they help them raise the level of their game.’ At Houlihan, the members of Jeff’s team knew that making the playoffs wasn’t the goal – we were expected to win a World Championship,’” Slonecker explained.

From the back-office to partner in just a few years

For the most part, investment bankers at the analyst level work hard and they clock in long, sometimes grueling hours. It would be impossible to find a successful banker who hasn’t put in the time and effort.

Others say Kramer was measurably different from those around him.

“He showed himself to be fanatical with an amazing work ethic,” another former colleague said.

Eventually becoming one of the top generators of business at Houlihan Lokey, Kramer had an atypical rise, going from the back-office to partner in a matter of six or seven years – all without an MBA.

“One of the many things that I will always thank Jeff and Irwin for is their commitment to maintaining a pure meritocracy in their group. Opportunities for advancement were available to anyone that earned them,” Kramer said.

In those early days at Houlihan Lokey, there wasn’t the typical hierarchy that was in place at traditional Wall Street firms. The restructuring group was a team of young analysts.

Werbalowsky told Yahoo Finance that Kramer was one of the “star analysts” in their small group.

“When we started out we had three star analysts in our small Houlihan restructuring group in LA — Dave Hilty, Mike Kramer and Eric Siegert. Twenty five years later those guys are certainly three of the top 10 restructuring bankers in the world, which I find amazing, and certainly explains the success we have all enjoyed,” Werbalowsky wrote in an emailed statement. Hilty and Siegert run Houlihan’s financial restructuring practice today.

Kramer recalled a conversation that he had with one of his mentors at Houlihan, Scott Adelson, who’s now the firm’s co-president. About six months into working as an analyst, Kramer told Adelson that he’d like to be an associate. That was usually a three-year process and required an MBA.

“He said it would never happen,” Kramer recalled.

It did, and they laugh about it today.

“My whole career has been about people telling me what I can’t do — and that inspired me to prove them wrong,” Kramer said, adding, “That’s very much a driving force.”

‘Fear’

When Yahoo Finance asked about the key drivers of his success during his earlier years, Kramer responded: “Fear.”

“I think that’s a good answer,” Slonecker echoed.

“I clearly had both a desire to succeed and a pretty healthy level of ambition,” Kramer added. “But there was always the fear of failure.”

He credits his success though to being around the right people.

“I’ve always tried to associate myself with the right people. I learned that working with Jeff and Irwin. And that is as strong today as it was then, as evidenced by my partnership with Derron and our other partners at Ducera.”

Slonecker added that the fear was about the feeling of not doing enough.

“What I saw early on was Jeff and Irwin’s ambition to dominate the field, and that really cemented the culture of our group,” said Slonecker. “It wasn’t necessarily the fear of failure. It was the fear of not delivering your best to help achieve our goals. We turned that fear into fuel. It was the healthiest hyper-competitive environment I had ever been a part of.”

The fear remains today, but it’s a different sort of fear.

Slonecker said to Kramer: “You say this to me every year, ‘Do you feel that knot in your stomach? If that ever stops, you’re not pushing hard enough.’”

“When I first started I was worried if I was going to get fired, whether I was doing a good job,” Kramer added. “Today, when I come to the office I have a list of things I want to accomplish that day – all centered on what I am going to do for my clients and my partners. I walk out every single day disappointed that I didn’t do enough.”

That said, Ducera is having a good year. A very good year, in fact.

“At our firm, we have the ability to create something that we’re proud of and that focuses on our clients,” Kramer said.

The next generation

But it’s not just about the current Ducera partners. They’re heavily invested in the younger generation.

“We have responsibilities that we take seriously. Because we know that it’s not just about us — we feel a deep responsibility to make this an interesting, career-progressing organization for our junior people,” Kramer said, adding, “We have to live up to the promises that we’ve made to the people that come to work with us. Sure, it’s economically rewarding. But money isn’t enough. People have to know that they’re learning and getting better.”

Ducera currently employs around 25 people. They’ve been drowned in resumes from the younger generation. A recent analyst recruit from a nontraditional Wall Street feeder school told Kramer that he’d “sleep in a box” if he was offered a job at Ducera. That analyst started at Ducera this past January.

What Ducera offers is a chance for the junior staff to be more entrepreneurial than they would be at other firms.

“We always talk about this. I probably believe in people more than they believe in themselves,” Kramer said, adding, “One of the things that we offer our people is the freedom to grow and succeed. We don’t say, ‘Here’s your lane, stay in it.”

Instead, they find a starting point and push their young talent to be the best — just like they were pushed in their early days.

“Even though these kids are coming to us right out of college, they are capable of a whole lot more than formatting a pitch book,” Kramer added.

The ideal candidate for Ducera is someone who’s willing to work hard, is a team player, thinks out of the box and understands that, at the end of the day, it’s all about delivering for their clients. It’s not about where they went to school.

Just like the partnership among the seven has been a key driver of success, they’d like to see the next generation build their long-term partnership.

“My goal is to make sure I surround myself with people that are better than me and help the people who are working for me become better than me. That’s not altruistic. I have a very specific agenda. In a business like ours, the way we are going to grow is by helping our junior people turn out the best work they can and build strong client relationships. These are the people who will replace me,” Kramer said.

Kramer later added: “Our biggest pitch to the young kids, frankly, is, ‘Look at me. I did it. If I can do it, you certainly can.’”

—

Julia La Roche is a finance reporter at Yahoo Finance.

Read more:

Billionaire Rubenstein: These 6 traits will help you succeed on Wall Street

How a $650,100 lunch with Warren Buffett changed one hedge fund manager’s life

Warren Buffett once said these are 2 of the more important decisions you’ll make in life

Buffett: Your business will succeed if you execute this 3-word mission

A hedge fund manager gave some blunt advice to a bunch of 9th grade boys