Brock Lesnar's case shows how UFC's anti-doping program is still failing its fighters

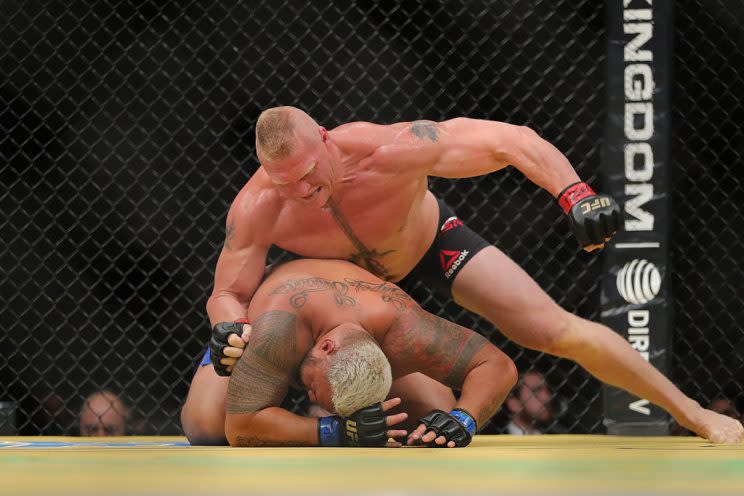

Brock Lesnar has been accused on Tuesday by the United States Anti-Doping Agency of failing yet another drug test administered to him, this one coming after his unanimous decision victory July 9 at UFC 200 over Mark Hunt.

That’s not the failed drug test that is so troubling, however.

What is so difficult to accept is that Lesnar also tested positive for the same banned substance on June 28, 10 days before the former heavyweight champion returned to the sport for the first time since 2011.

He was randomly tested on that date – which is good – but results weren’t returned until July 15, or six days after his bout.

That is not only egregiously bad, it is sickening. It is horrendous. It is dangerous. It raises doubts about the entire anti-doping program’s credibility.

It makes a mockery of the process and of the fighters who dutifully do the right thing and compete clean but still have to go through the rigmarole of filing whereabouts reports and spending money to have their supplements tested.

Lesnar isn’t the first athlete to have failed a test and be allowed to compete because the results weren’t in on time. It has happened numerous times previously, which defeats the entire purpose of the testing.

The UFC is paying millions to have its athletes tested to ensure clean sport, but moreso to prevent a tragedy. The fight game is dangerous enough without a juiced-up fighter pushed beyond his limits by drugs being allowed to compete. It’s a fatality waiting to happen.

So despite all the hassles and difficulties that go along with it for the athletes, the testing is a good thing. The UFC has by far the most stringent anti-doping platform in sports.

It is catching cheaters – plenty of them – which it is designed to do. But for some reason, the tests often take so long to process that the results aren’t in by the time the fighter competes.

Of course, no one can explain on the record why this occurs.

Through a spokesman, Jeff Novitzky, the UFC’s vice president of athlete health and performance, deferred questions to USADA.

A USADA spokesman said Tuesday he wouldn’t be able to discuss in-depth until Thursday.

Lesnar’s attorney didn’t return a message seeking comment.

And Anthony Marnell, the chairman of the Nevada Athletic Commission, was willing to talk, but said he didn’t have jurisdiction at the time.

The Nevada commission passed its new rules on Monday that give it both the money and the legal authority to make certain that results will be returned in time before a fighter competes.

But the Lesnar incident happened before the commission’s new rules were passed, so Marnell was powerless to order a rush on the tests.

He will have the ability in the future, but that will only apply to fights held in Nevada, so it’s a tiny fraction of the total.

“Right now, I’m very pleased with [the UFC/USADA] program, but I’m very displeased with the timeliness of the reports,” Marnell said.

The Los Angeles Times reported Tuesday that Lesnar tested positive for clomiphene, though Yahoo Sports could not independently verify that.

But Lesnar was tested six times, and passed all of them, from the time the UFC announced on June 4 that he would return to the sport to compete at UFC 200, until June 28.

Lesnar failed on June 28, in his seventh test, and again on July 9, his fight-night test. When Lesnar’s first failed test was made public last week, Lesnar released a terse statement to the Associated Press in which he said he’d get to the bottom of it.

He has the right to have the B sample tested, but hasn’t said whether he’ll do it.

That is of secondary concern, though, to the unanswered question as to why the results couldn’t be released in time.

The standard answer has been that the tests are sent in anonymously so that no one in the lab knows whose sample is being evaluated. The fighter’s sample is given a code and no one at the lab has the ability to find out the provider of the sample.

So, unless there is a rush marked, the sample falls in line and is tested in order.

The professional golfers who are playing in the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro next month are being tested. There is no need to rush their tests.

It seems to be common sense, but apparently is not, that when you test a powerful 265-pound man who is going to be allowed to punch or kick someone in the head, the results should be returned and analyzed before he competes.

There needs to be time to yank him from a fight card if he fails a test.

It seems simple in theory, but it has been agonizingly difficult to pull off in practice.

One source who is somewhat familiar with the process and who requested anonymity because he’s not permitted to speak publicly about it said there is an ability to put a code into the number that would cause the test results to be expedited.

He couldn’t answer why that isn’t routinely done.

All the testing is worthless if those who are using aren’t prevented from competing.

Lesnar, of course, deserves due process. He has the right to an appeals process if the B sample confirms the original results.

He doesn’t, though, deserve the ability to fight when he hasn’t passed the tests.

Not getting the results in time creates suspicion that the testing is corrupt and that big stars are being favored.

Anderson Silva failed a test given to him by the Nevada Athletic Commission before his 2015 bout at UFC 183. Results didn’t come back quickly enough and Silva went on to fight Nick Diaz, despite a failure.

He clearly is one of the company’s biggest stars ever.

Lesnar, too, is a massive star, as evidenced by the $2.5 million guarantee he received for his bout against Hunt. It was 2 1/2 times larger than any guarantee the UFC ever paid previously. Conor McGregor was guaranteed $1 million at UFC 194.

In 2015 with Silva, the delay in processing the sample came on a test ordered by the Nevada commission and screened at the WADA-accredited lab in Salt Lake City.

In 2016 with Lesnar, the processing delay came after a test ordered by USADA and screened at the WADA-accredited lab at UCLA.

In both cases, the tests did their jobs and caught athletes with banned substances in their systems.

The system failed, though, and didn’t prevent them from competing.

Given that, this is the simple truth: Despite all the hype, the aggravation and money invested, until that issue is solved, the UFC’s anti-doping program is worthless.

When you catch the cheaters and don’t prevent them from competing, it’s worse than not trying to catch them at all.