From immortal to quite mortal, Kentucky's Unforgettables face midlife challenges 25 years after their greatest moment

“One of those men who reach such an acute limited excellence at twenty-one that everything afterward savors of anti-climax.” – F. Scott Fitzgerald, describing former college football star Tom Buchanan in “The Great Gatsby.”

Two shots went arching through the Philadelphia air some 25 years ago. One was a prayer that thudded off the plexiglass and in, a fortunate fluke for a hard-luck kid, a basket that briefly tilted an entire sport on its axis. The other came 2.1 seconds of game time later, a clean swish from a smug superstar off a perfect pass from a golden child, a response that restored order while leaving a nation gasping at the dramatic excellence of it all.

Thus ended Duke 104, Kentucky 103, on March 28, 1992. Thus began the game’s canonization as the greatest in the history of college basketball.

The game retained that status without serious challenge until last April in Houston, when North Carolina and Villanova came up with a reasonable facsimile of the endgame shot-making with the national championship on the line. But even that classic carried less sustained offensive artistry, less emotional cargo and less karmic context than Duke 104, Kentucky 103.

Especially for the losing side. In particular, for the Kentucky senior class known as “The Unforgettables”: John Pelphrey, Sean Woods, Deron Feldhaus and Richie Farmer.

A quarter century later, that quartet of overachieving Wildcats is as ennobled in defeat as the Blue Devils were celebrated in victory. That runs counter to the prevailing ethos of American sports, where winning is considered everything. The vanquished rarely are so respected, so exalted, so beloved for coming up agonizingly short.

But as the years pass and lives progress, the four Kentucky seniors who were so valiant may feel a bit like Tom Buchanan. Like everything after that night of acute limited excellence savors of anti-climax.

Their performance in that historic game brought full authenticity to their nickname. They were Unforgettable. They were, as young men, basketball immortals.

What’s followed has been a reminder of how mortal they are as adults.

– – – – – –

Richie Farmer returned the phone call quickly, friendly as ever, sounding happy to renew an old acquaintance. The call was an invitation to relive some of his glory days, one 25-year-old basketball game in particular. For Farmer, talking about the past is much easier than discussing the present.

When he heard the standard small-talk question – “How you doing?” – he laughed mirthlessly.

“Oh,” he said, in his familiar Appalachian twang, “I’m hangin’ in there.”

One of the most adored athletes to ever shoot an orange ball through a hoop in basketball-obsessed Kentucky is, in fact, struggling to hang in there. He filed for bankruptcy last year, several months after being released from federal prison, and the details of his filing were grim: Farmer stated that he was getting by on $194 a month in food stamps, plus assistance from his parents. He was more than $360,000 in debt.

His No. 32 jersey hangs in the rafters of Rupp Arena, but for 20 months Farmer was No. 16226-032 in the federal penal system in West Virginia after pleading guilty to misappropriating public funds while the Kentucky state agriculture commissioner. Since being released, a man whose folkloric popularity put him on the Republican ticket as a lieutenant governor candidate in the 2011 election now feels more like a pariah.

Finding work has been difficult. Currently he spends his days in his hometown of Manchester, an old coal town in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky, waiting for a break.

“It’s been the most difficult thing I can ever imagine,” said Farmer, a divorced father of three boys. “The people of this state have been great to me my whole life. I want to say thank you to all of them.

“I would like to work dealing with people. I know I have a lot of support and would be an asset to a company. I know the Lord will lead me in the right direction.

“There’s no disgrace to get down. It’s a disgrace to stay down.”

Farmer was down the day he was released from incarceration. Way down. The following day, he went to see the man who arguably did more to lift him up than any other.

He visited Rick Pitino in Louisville.

His old coach at Kentucky told him he didn’t want to talk about where Farmer had gone wrong. “That’s buried,” Pitino said. He wanted to talk about the overweight, homesick, overwhelmed guard he inherited who rose from bench jockey to double-digit scorer as a senior.

“Let’s talk about LSU,” Pitino said, referring to a 1990 game Farmer clinched with six late free throws as the undermanned Wildcats shocked a team that featured Shaquille O’Neal, Chris Jackson and Stanley Roberts. “Let’s talk about Duke.”

Pitino was attempting one last motivational ploy with Farmer.

When Pitino surprisingly left the New York Knicks to take over a probation-ridden Kentucky program in 1989, he inherited a threadbare roster. There were eight scholarship players, none of whom had done much of anything on the college level. The good ones had transferred away, fleeing devastating NCAA sanctions.

What was left was nothing special – mostly a bunch of guys who loved Kentucky basketball from the crib and would never leave it, even in the worst of times. But one of those holdovers was a bigger deal in the commonwealth than even the new coaching savior from the NBA.

That was Farmer, a 5-foor-11 hillbilly who lacked the quickness to play the point or the height to be a shooting guard. He had been a mythic figure at Clay County High School, scoring the most points in the history of the Kentucky state tournament and leading his school to a split of two epic championship matchups with Louisville Ballard High and future NBA All-Star Allan Houston. Farmer scored 88 points in those two games alone.

But the lifelong dream to play at Kentucky had gotten off to a difficult start under the coach who recruited him, Eddie Sutton. Farmer averaged three points a game as a freshman and backed up the coach’s son, Sean, which led to considerable outcry from the mountain people who revered Richie.

When Pitino arrived and a player exodus ensued, Farmer had his chance. But first the former coach of the Knicks had to tear down his chubby little rock star and rebuild him via a merciless conditioning program.

“Pitino was the best thing that ever happened to Richie,” said Chris Cameron, the sports information director at Kentucky at the time.

The best, perhaps, but not the easiest. With Pitino and strength coach Ray “Rock” Oliver pushing him to the brink, Farmer contemplated quitting and going home to Manchester multiple times. Ultimately, though, the makeover worked. His minutes increased by necessity as a sophomore and by merit as a junior and senior.

Neither Richie Farmer nor Rick Pitino would allow a mountain legend to become a bust.

He had come so far from the very first game his freshman year – a blowout loss to none other than Duke, a game in which he played seven scoreless minutes. By the time his career came full circle with another game against Duke on March 28, 1992, Richie Farmer was ready for a different outcome.

– – – – – – Unlike Richie Farmer, Sean Woods did not call back.

The man who scored the last Kentucky basket in that game 25 years ago, who brought the Wildcats to the brink of the Final Four and dethroning Duke, is in a similar position to Farmer – trying to dig out, trying to get a career back on track, trying to recover from problems he brought upon himself.

Woods was in Vanderburgh Superior Court in Evansville, Ind., March 13, answering to misdemeanor charges of battery resulting in bodily injury. The charges were brought by two of his former players at Morehead State, who alleged they were assaulted by their coach during a game at Evansville last November. The court ordered Woods into a six-month diversion program, and to pay $1,080 in court costs and restitution.

It was Woods’ second instance of alleged player abuse at Morehead. The first earned him a one-game suspension in 2012. The second led to his resignation in mid-December, a few weeks after being suspended based on the incident in Evansville. He spent much of the winter watching his son, DeSean, play for Rowan County High School.

“That’s what’s been keeping me going, is being able to watch him play,” Woods told the Ashland (Ky.) Independent in late January.

Getting another coaching job at any level with that on the résumé will be difficult in the current climate, if not impossible. That reality is likely hitting home right now, with the coaching carousel in full spin.

“He’s going through a difficult time,” said one longtime friend.

Woods never did have easy head-coaching jobs. He was at Mississippi Valley State, one of the lowest programs on the Division I food chain, from 2008-12, parlaying a 21-13 record and an NCAA bid his final season there into the Morehead job. Woods had a winning record both overall and in conference play in four-plus seasons at the school 65 miles east of Lexington, Ky., but never got back to the NCAAs before losing his job nine games into this season.

Pelphrey believes Woods will be OK, even if it takes a while.

“Sean has that upbeat personality,” Pelphrey said. “He never goes long without a smile on his face.”

The fact that Woods had been so close to being the hero 25 years ago was one of the cruelest elements of that loss. It was finally going to be his redemption, after a few mishaps throughout his career.

Pitino kept putting the ball in his point guard’s hands at the end of games, and it never quite seemed to go right. Early in their first year, 1989-90, he had Woods drive late against Indiana, down two – he couldn’t convert. The following year at Mississippi State, down three in the final seconds, Woods got confused on the score and drove for two.

There was one other ill-fated drive – in a car. Woods took recruit Clifford Rozier, a North Carolina transfer, to a Kentucky Derby party in Louisville and violated the NCAA rule prohibiting going more than 30 miles off-campus on an official visit. Kentucky stopped recruiting Rozier, who wound up being an All-American at rival Louisville.

The final drive of Sean Woods’ Kentucky career, into the lane, did not go as planned, either. The senior from Indianapolis took an inbounds pass from Farmer, dribbled off a Pelphrey screen at the top of the key that stopped Duke’s Bobby Hurley cold, and then was supposed to pass it back to Pelphrey for the shot. (Kentucky’s star, sophomore Jamal Mashburn, had fouled out of the game after scoring 28 points. Options were limited.)

“The play was not designed for him to shoot a 12-foot floater over Christian Laettner,” Farmer deadpanned.

Instead, Woods drove the ball into the lane and let it go, with exaggerated arc to clear the long arm of a lunging, 6-foot-11 Christian Laettner. It was a prayer of a shot that somehow was answered.

“My first reaction was, ‘Yes, we won and we’re going to the Final Four,’ “ Pelphrey recalled. “My second was, ‘I’m so happy for Sean, he deserves it.’ “

He deserved it. But he didn’t end it.

– – – – – – Deron Feldhaus was terribly busy but returned the call anyway. He alternated between talking into the phone and to a mechanic who had arrived at Kenton Station Golf Course to repair some equipment.

Feldhaus co-owns and operates the nine-hole course in his hometown of Maysville, Ky., with his father, Allen. Thirty years ago, he played for Allen at Mason County High School, then followed his dad’s footsteps as a player at Kentucky.

Deron’s older brothers, Allen Jr., and Willie, are successful high school coaches in the state. But the best basketball player in the family wanted no part of that family business – after a four-year pro career in Japan, Deron just wanted to get into the golf business with his father.

“I’m not making much money,” he said. “But I’m working outdoors and working with my dad, which is pretty nice.”

Allen Feldhaus played at Kentucky for Adolph Rupp. That was during the days before John Wooden’s dominance took hold at UCLA, when Kentucky was the pre-eminent power in the sport. If Deron’s 9-year-old son, Jake, should become a player worthy of becoming a Wildcat, he, too, will play in an era of Big Blue dominance.

Deron Feldhaus played in that rare patch of history when Kentucky could actually be an underdog.

“We weren’t expected to win as much as we did,” he said. “Most of the time at UK, they’re expected to win every game.”

Feldhaus’ class ushered in the return to elite status.

Feldhaus was perhaps the most forgettable Unforgettable. He wasn’t a statewide phenomenon like Farmer. He didn’t have the ball in his hands all the time like Woods. He didn’t fill reporters’ notebooks like Pelphrey.

But the 6-foot-7 Feldhaus was a handyman for Pitino on the court. When the undersized Wildcats needed help defensively inside, they would throw Feldhaus into the breach. When they needed someone to sit on the perimeter and make 3-pointers against a Dale Brown “Freak” defense, Feldhaus dropped six of them on LSU.

And when they needed someone to score a basket to tie the game against Duke at 93 near the end of regulation, Deron Feldhaus was the man for that, too. Everything that happened thereafter – the drama-drenched five lead changes in the final 31 seconds, the Woods shot, the Laettner answer – would not have happened without that basket.

– – – – – – College basketball coaches are permanently busy, but Alabama assistant John Pelphrey always returns the calls. Even this time of year. Even when he knows what topic is coming to thump him upside his redheaded noggin yet again.

“I have a hard time appreciating it,” Pelphrey said. “I appreciate playing at Kentucky, being in the NCAA tournament and being coached by that guy. I appreciate the relationship with the team and the fans. But the game is a moment in time where we never get to put the jersey on again. And it wasn’t just any jersey; it was a special, special piece of cloth.”

It’s risky to identify anyone as the quintessential in-state Kentucky basketball player, but Pelphrey would make a good choice. All he ever wanted to do was be a Wildcat.

Reared in Paintsville, another mountain town in the eastern part of the state, the annual family vacation was to the state tournament. When he became good enough to be a standout at Paintsville High, he could dare to dream of actually getting the attention of the Kentucky coaches. The possibility drove him every day.

“My senior year I was up at 5:30, running through town at 6, challenging myself that if you get a chance, you’ve got to be ready for it,” Pelphrey said. “I went to Senior Day [in 1986], and when you experience that you become consumed by it. Just give me a chance.”

Eddie Sutton gave Pelphrey a chance, but not much of one. He was redshirted his first season and barely played his second. By the time Pitino got him, Pelphrey was a 21-year-old who had scored 38 career points.

By the time Pitino was finished with him, Pelphrey had scored 1,257 points and been part of 65 victories in three seasons. This at a time when many thought the depleted Wildcats would be lucky to win 10 a year.

If any Unforgettable was destined for coaching, Pelphrey was it. He often spent time his senior year going over film in the office of a young assistant coach – a guy named Billy Donovan. After a brief stint with Eddie Sutton, Pelphrey went to work for Donovan and eventually became the head coach at South Alabama in 2002.

That was a rebuilding job, but Pelphrey got it done – he won 20 games in his fifth and sixth seasons, advancing to the NCAA tournament in year five. That led him to Arkansas in 2007-08 to replace Stan Heath.

Pelphrey’s first Arkansas team went 23-12, made the NCAA tournament and beat Indiana before being eliminated by eventual Final Four team North Carolina. But when six seniors graduated and star sophomore Patrick Beverly unexpectedly turned pro, the program was plunged into a rebuilding process.

Two losing seasons ensued. When Pelphrey got Arkansas back above .500 in year four at 18-13 but didn’t make the NCAAs, he was fired.

A guy who had seemed like a can’t-miss, big-time head coach had somehow missed and been shuffled back to the assistant ranks. Six seasons later, Pelphrey is still waiting for another chance to show he can do the job.

“He’ll be a great head coach again,” Pitino said. “John is a terrific basketball mind and an outstanding recruiter. He just needs an opportunity.”

When Tubby Smith left Kentucky in 2007, Pitino said at the time the program should hire Pelphrey. It almost seemed like manifest destiny.

“Nobody would take the job more seriously and work harder than Pel,” Pitino said. “He loves Kentucky more than anyone else.”

But Pelphrey was still at South Alabama then and it would have been a quantum leap in scope. Still, he probably would have been better than the man who did replace Smith, Billy Gillispie, who was unceremoniously fired two years later.

Yet that cleared the way for John Calipari, which has closed the window on anyone dreaming of that job opening for the past seven seasons. And when it does open, they’ll be looking for someone with a résumé better than what Pelphrey’s is to date.

The timing was never quite right for John Pelphrey to land his dream job. Just as it wasn’t quite right on his final play in a Kentucky uniform.

– – – – – – For quite a while afterward, Pelphrey was sure he actually had his hands on the pass. He thought it was his. His mind completely deceived him.

When Grant Hill, the golden Dukie, wound up and threw that baseball pass three-quarters of the court to Laettner, Pelphrey and Feldhaus were playing behind the Blue Devils center. They were mindful of Pitino’s last words coming out of the huddle with 2.1 seconds left:

“Don’t foul.”

Alas, they proved coachable to the end. Too coachable.

When Laettner went up to catch the ball, Pelphrey made an initial lunge at it and then backed away, clearly worried that he might foul a guy who was 10-for-10 on the night from the free throw line.

“I can literally remember at that moment that I had both hands on the ball and it was over,” Pelphrey said. “It wasn’t until days later when I watched that I saw I never touched it.”

With Pelphrey backed away and Feldhaus dwarfed, Laettner executed with uncanny poise. Not just catching the ball, but taking the time under extreme time constraints to get a balancing dribble in before turning and shooting. His internal clock was flawless.

“I was thinking, ‘Where’s the horn? Why isn’t it going off?’ ” Pelphrey recalled.

When Laettner let it go, everyone knew.

“I had a good look at it from under the basket,” Farmer said. “There was no doubt it was going in.”

And that’s how suddenly a dream dies. A career ends. Kentucky’s rare Cinderella window was abruptly shut.

After a lost freshman season and a coaching change and two years of NCAA postseason bans, the four-year wait for One Shining Moment came shockingly close to the ultimate fulfillment. Until it vanished in 2.1 seconds.

During the timeout between Woods’ shot and Laettner’s shot, the whole journey crystallized for Cameron, the SID.

“If you lived the three years before, you’re almost thinking, ‘We deserve to win this game,’ ” he said. “It wouldn’t be right for those four guys not to win this game. It would be one of life’s unfair moments.”

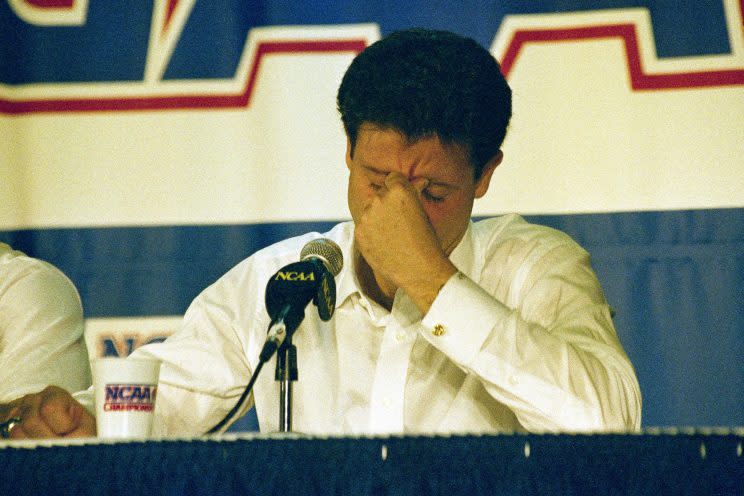

Unfairness won. Duke’s defending national champions moved on to the Final Four, and a repeat title. Kentucky’s players, emotional wrecks, retreated to “the most devastated locker room I’ve ever been in,” as Cameron recalled.

Trying to console his team, Pitino fished a 1989 Sports Illustrated out of his briefcase and showed the players. “Kentucky’s Shame,” read the headline, detailing the program’s fall into disgrace and probation. He told the Wildcats that they had eradicated the shame and restored the pride.

Nobody felt better.

Outside the locker room, late on a Saturday night, deadline-stressed reporters impatiently asked to get in to conduct interviews when the mandatory cooling-off period had ended. Cameron, a consummate pro, went into protective mode.

“Over my dead body,” he said.

“That can be arranged,” a reporter said in response.

Finally the doors were opened, and even the most tenacious reporters suddenly felt like trespassers. The trauma was palpable. It was the saddest locker room I can remember.

“This was our one shot,” Pelphrey said. “We put so much into it. A lot of things ended that night.”

When the team returned to the Warwick Hotel, the scene in the lobby wasn’t much better. The players were surrounded by distraught, crying fans who were projecting their grief back onto the grieving players.

Cameron surveyed the scene and decided he had to get the Unforgettables out of there. He got his assistant, Rena Vicini, and they snuck the players through the Warwick kitchen, out a back door and to the nearby media hotel, where Vicini had a room.

They went to her room and emptied the minibar that night with the four players. There were some laughs at last, and a hangover or two in the morning when it was time to fly home.

The only thing left was a postscript none of the four saw coming.

– – – – – – The next week, athletic director C.M. Newton called Pitino and Cameron in for a meeting. Suitably moved by the careers of the Unforgettables and the way it ended, Newton made a bold decision: They were retiring their jerseys to the rafters of Rupp, and doing it now.

This was unprecedented – none of the four had statistics worthy of inclusion in this select club, alongside the likes of Hagan and Issel and Givens and Walker. And it usually took many years for these honors to be bestowed.

But Newton was a UK alum with a full sense of the program, and he applied that context. This was not a prisoner-of-the-moment rash decision. These players were simply that important and that selfless in rescuing Kentucky basketball, and they had just played the greatest game anyone had ever seen.

Nothing more was needed but top secrecy, preparing for the celebration ceremony that would be held in Rupp a few days later. The arena people had to be clued in, and the outfit in Louisville that makes the banners, but word never leaked.

“These were all Kentucky basketball fans,” Cameron said. “They would guard that secret with their lives.”

Thousands of fans came to Rupp just a few days later for what they thought was simply a chance to honor the senior class one more time. The players themselves took the floor with no idea anything extraordinary was happening.

When Newton told The Unforgettables to look to the rafters, they suddenly knew. They grew up awed by the program’s history, and now were awed by their sudden place of honor within it.

“I was totally shocked,” Feldhaus said. “Every time I go into Rupp, I have to check it to make sure it’s there.”

Said Farmer: “I used to look up and think, ‘Wow, what a history.’ All I’d ever done in my life is play basketball, and I thought there was no way I’d ever be up there. To have my jersey retired at the University of Kentucky was the ultimate.”

In that moment, their paradoxical career arc was complete. Nothing these four men could have done – not beating Duke, not winning a national title – could have made their place in Kentucky history any more secure. They achieved a unique niche in program lore by losing, by going out in a blaze of unfulfilled glory.

Having strived for so long to reach that moment of acute limited excellence, the anti-climax that followed was almost inevitable.

– – – – – – Of course they still keep in touch. It’s sporadic at times – a couple of weeks, maybe, between calls or texts. But even in their 40s the bond is unbreakable, the memories living up to their collective nickname. They’ve shared in each other’s good times and helped each other through the hard times, teammates once and for all.

“We’re very, very close,” Pelphrey said. “The moments are very fresh and detailed and clear. I love and care about those guys, not just because of that game but because of everything together.

“We’ve gotten together over the last 25 years, all of us and Coach, and I can’t tell you how wonderful it was. This Italian mafia-speaking guy from New York City, for some reason he just fit with some guys from Kentucky. We’re still captivated by him.”

Kentuckians and many other college basketball fans are still captivated by this team. The one that walked away heartbroken from an athletic masterpiece. The most compelling of all losing teams.

Young men immortalized in defeat, The Unforgettables now are navigating a very mortal adulthood. But they’ll do it together.

Popular college basketball video on Yahoo Sports: