Betting threat

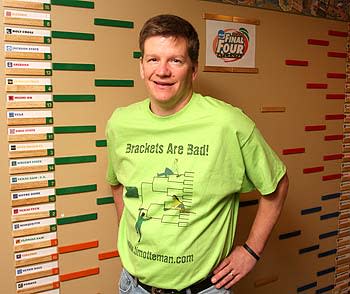

Tim Otteman, a gambler-turned-researcher conducted a study on student-athletes and gambling for Central Michigan University.

(Photo courtesy: Robert Barclay, Central Michigan University)

MOUNT PLEASANT, Mich. – Copy machines across America have been working overtime this week, spitting out brackets for betting pools that have become as popular as NCAA basketball tournament itself, while a little-known researcher here has been finishing a study that could stun college officials otherwise swept up in March Madness.

The study indicates illegal gambling has a tighter grip on college athletics than many people thought.

For years, the NCAA has denounced gambling like one might decry a heinous crime. It fought hard but unsuccessfully to bar Las Vegas sports books from taking bets on college games. It prohibits athletes and coaches from taking part in any form of gambling involving college or pro sports – yes, even filling out brackets for pools with modest entry fees. Yet despite the get-tough stance, a study from Central Michigan University suggests illegal gambling that involves inside information obtained from student-athletes and others connected with teams requires a beefed-up approach if there's any chance to get it under control.

Student-athletes aren't the only ones at fault, said Tim Otteman, a gambler-turned-researcher who conducted the study. School administrators are ill-equipped to spot and stop sports gambling, according to Otteman, who urges colleges to increase education and vigilance. But his recommendations figure to generate less attention than his findings.

Since 2003, the NCAA has cited the results of a confidential survey that indicated a small fraction of its athletes provided inside information to gamblers. But Otteman is completing a dissertation that suggests the problem of gamblers obtaining inside information is widespread.

The Study

"Gambling With Their Lives: College Students and Sports Gambling"

KEY FINDINGS

• Student bookmakers and gamblers obtained inside information from student-athletes and other people associated with athletic teams.

• Students' involvement in sports gambling progressed from brackets and pools to online gambling and wagers with bookmakers

• Students used campus equipment and facilities to participate in sports gambling

• Sports gambling is a behavior easily hidden, as opposed to alcohol or drug use, and the social acceptability of gambling fosters the behavior

RECOMMENDATIONS

• Universities should strengthen enforcement and closely monitor equipment and facilities that can be used for sports gambling

• Launch university-wide, anti-gambling campaigns as part of increased education

• Replicate the study at other institutions, including schools with different-sized enrollments and schools located in different regions of the country

• Conduct additional research focused specifically on student-athletes, faculty and university officials

METHODOLOGY

Researcher conducted interviews with 14 students – 13 male and one female – and gave them an opportunity to review the transcripts for clarification and correction. Because the students were admitting involvement in illegal activity, the researcher took steps to protect confidentiality.

Researcher Tim Otteman, a faculty member at Central Michigan University, is a recognized authority on sports gambling and has addressed the subject in frequent lectures for college students, student-athletes and university administrators. More information can be found at www.timotteman.com.

Three student bookmakers and a gambler at a mid-sized, Division I university in the Midwest told Otteman for his research that they obtained inside information from student-athletes or others associated with teams for gambling purposes. If the practice is just as common at the more than 300 colleges that field Division I basketball teams, as Otteman suspects, hundreds of student bookmakers and bettors are getting inside information.

"It doesn't surprise me," said Dion Lee, convicted for his involvement in a 1995 point-shaving scheme when he played basketball at Northwestern University.

Lee was one of two players implicated in game-fixing that included the involvement of former Notre Dame kicker Kevin Pendergast. After being linked to the scandal, Lee contended as many as two dozen athletes at Northwestern regularly wagered on college or pro sports.

"My stance on what I said then hasn't changed," Lee said during a recent phone interview. "This is how bad it is (on college campuses). People say you've got to worry about alcohol and drugs. You've got to worry about alcohol and gambling."

An NCAA official said to call gambling's impact on the integrity of college games a "crisis" overstates the case, but that the NCAA considers gambling a serious problem.

"We have never taken a position that we don't believe that this is going on on our campuses," said Rachel Newman Baker, who oversees issues related to gambling, agents and amateurism for the NCAA. "Not just with the student population, but with student-athletes as well."

When asked for her response to the prospect of hundreds of student bookmakers and bettors across the country getting inside information from student-athletes and others connected to teams, Baker said she had not had a chance to review the findings of Otteman's study. But she said the NCAA has tried to be "as proactive as possible" in warning students about people who unscrupulously seek inside information during casual conversations with the athletes.

SOUNDING THE ALARM

Otteman, calling the exchange of inside information "an alarming discovery," concluded in his dissertation, "This enlightens us to how student-athletes and athletic department personnel were accessed by the betting public and may jeopardize how Americans view collegiate sports. In general, consumers of sports make the assumption that the outcome of intercollegiate and professional sports events is not pre-determined. If these results are pre-determined or the perception of the contests is tainted by informational improprieties by athletes and administrators, college athletics could suffer a blow from which they could not recover."

Taking steps to head off such a crisis, the NCAA works with Las Vegas Sports Consultants Inc., a group that tracks betting lines and looks for irregularities that indicate corruption might be taking place. During the opening rounds of the 65-team tournament that starts Tuesday, the NCAA will have three officials in Las Vegas to help monitor gambling activity. But as Otteman pointed out, experts say only 1 percent of the billions of dollars annually wagered on college sports is bet legally through Las Vegas, suggesting point shaving or bets stemming from inside information could escape detection.

"Bracket Busted," is what Otteman calls the lecture he has given to student-athletes and administrators at Central Michigan. "Brackets Are Bad," reads a slogan on one of the T-shirts he'll pass out at future lectures. At the same time, Otteman acknowledges that most office pools and recreational gambling are harmless fun.

"But nobody becomes an alcoholic before they take their first drink," he said. "Nobody becomes a compulsive gambler until they make their first bet. And for a lot of people, the bracket is the first time they make a bet."

Otteman declined to say where his study took place, citing a pledge to protect the confidentiality of the students he interviewed. But Otteman said the school where he did his research is "immaterial" because he's convinced the same problem exists on campuses across the country, and previous studies support his view.

Major scandals

"Gambling With Their Lives: College Students and Sports Gambling"

Below is a list of major gambling scandals in college athletics.

1951: The City College of New York, a year after winning the national championship, was implicated in a game-fixing ring that involved a half-dozen other schools, more than 30 players and organized crime.

1963: Thirty-seven basketball players from 22 schools were caught in a scheme to fix games.

1981: A Boston College basketball player and four others were found guilty of point shaving.

1985: Four Tulane basketball players, including star John "Hot Rod" Williams, were arrested and accused of point shaving, prompting Tulane to shut down its basketball program for four years.

1994: Northwestern running back Dennis Lundy was suspended for gambling and point shaving.

1996: Three Boston College football players were accused of betting against their team, and 13 players in all were suspended for betting on college football, pro football and baseball.

1997: Two Arizona State basketball players, Stevin "Hedake" Smith and Isaac Burton Jr., pleaded guilty to a point-shaving scheme.

1998: Northwestern basketball player Dion Lee and former Notre Dame kicker Kevin Pendergast were convicted of their involvement in a point-shaving scheme.

2001: Florida guard Teddy Dupay was linked to a gambling investigation and declared ineligible for the 2001-02 season, ending his college career.

Source: Multiple published reports

Justin Wolfers, an assistant professor of business and public policy at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, studied the 44,120 NCAA basketball games played between 1989 and 2005 and, based on scores and point spreads, concluded that nearly 500 games had involved "gambling-related corruption."

Additionally, a 1998 study conducted by the University of Michigan revealed that more than five percent of male student-athletes admitted they wagered on a game in which they participated, provided inside information for gambling purposes, or accepted money for performing poorly in a contest.

The NCAA is conducting another confidential survey this year, and Baker said she's looking forward to seeing the results in part because the popularity of poker likely has increased gambling on campuses, But Otteman said he wanted to look beyond the numbers.

He brought unusual credentials to the task.

FAMILY BUSINESS

While attending Central Michigan as an undergraduate student in the late 1980s, Otteman said, he gambled on sports and made $6,000 to $10,000 a year. He placed some of his bets with his younger brother, who said he ran an on-campus bookmaking operation that took in up to $30,000 a week. His brother, who requested his name be withheld because he feared his past gambling activity could damage his reputation, said he ended the operation when athletes at Central Michigan wanted to place bets on college games and he feared authorities might learn of his involvement.

Similar fears pushed Otteman's father out of the gambling business.

Milton Otteman said he used to make up to $700 a week distributing parlay cards used to gamble on a combination of games and facilitated about $1,000 in bets a week through a bookmaker in Lansing, Mich. Milton Otteman said after federal authorities arrested the Lansing bookmaker in the mid-80s, he immediately stopped taking bets and distributing parlay cards. Yet he said he still checks odds every morning and gambles "recreationally," as does Tim Otteman's younger brother.

"The family that gambles together stays together," Milton Otteman said, chuckling.

But Tim Otteman, 42, said he hasn't placed a bet since he was a senior at Central Michigan and in recent years has turned his attention to studying the behavior and culture that led him to gambling thousands of dollars as a college student.

After joining the faculty at Central Michigan in 1999, he created a course called "Bettor Education: The Impact of Sports Gambling on College Campuses." Last year, upon learning of Otteman's ongoing research, the school's athletic department asked him to speak to its athletes about the dangers of gambling.

Though Otteman said he never got inside information from athletes or anyone connected with college teams when he gambled, he said he had suspicions a year ago when he spoke in front of about 250 athletes.

"You, as a student-athlete, cannot bet on sports," Otteman told them. "No exceptions to the rule."

At times the athletes were so quiet, one could have heard a poker chip drop.

"Last, but surely not least – this is the one that student-athletes miss – you cannot be involved with any exchange of information about you or your team, consciously or not," Otteman warned. "… The consequences include suspension or expulsion from school, loss of your scholarship, jail and the elimination of any potential to compete professionally."

BEHIND THE STUDY

At the time of the lecture, Otteman was seeking participants for the study that is part of his dissertation. He said he spoke in front of more than 1,000 students and 14 who were self-admitted gamblers volunteered to take part. Three said they were bookmakers and another eight said they used bookies or online betting services, according to Otteman.

The interviews with those students, Otteman said, produced a wealth of information and confirmed his suspicions about inside information – much of which he said he thinks athletes disclose in passing and unwittingly.

Otteman says experts claim only 1 percent of the billions of dollars annually wagered on college sports is bet legally through Las Vegas.

As part of his agreement with Central Michigan administrators who approved of the study, Otteman destroyed audiotapes of interviews with the 14 students and threw out their contact information and assigned them pseudonyms.

He provided portions of the written transcripts to Yahoo! Sports and a summary of his findings. Direct quotes from the students are part of the following excerpt from Otteman's study.

"Adam" explained how he used student-athletes at a variety of colleges to gather important gambling information:

"There is a big Division I university where one of my good friends from high school goes. He lives with one of the players on the football team, so he gives me so much inside information about who's injured, what the game plan is, that I would always bet with the team or against them depending on what he told me. And I still do to this day. Here, I ask players for information and they give it to me which helps me out with my betting."

"Jacob," who bet himself and ran a bookmaking operation, stated: "(I ask) people involved with sports. They know stuff that doesn't get to the media. But, it is stuff that helps gamblers. How someone is doing in school, financial problems, social things with girlfriends. This is really true with college students. I get stuff all the time from other students about athletes on campus."

"Ferris," who also operated as a bookie, echoed Jacob's comments: "The best information comes from players or people tied in some way to the team, like trainers, student managers, walk-ons. The best part is that they want people to know they are associated with the team, so they want to talk. Information may also come from kids who have players in class or know them from the dorms. I get information all the time from friends who go to other schools and hear stuff."

Based on their experiences, two students suggested that student-athletes and members of athletic departments not only provided important information to sports bettors but also may be involved in shaving points or fixing games. The term "shaving points" refers to altering the outcome based on the point spread, while "fixing" games is defined as pre-determining the result of the athletic contest.

"Hunter," who bet on games and served as a bookmaker to five students who bet large amounts, shared a story regarding a wager he placed based on information that the game was being fixed. He elaborated:

" (It was a college football bowl game) in 2004. It all started out through the one friend from high school. I called him my gambling partner, we did everything together. We would travel all over gambling. (He) calls me that morning and says, 'Hey my dad's friend just had someone bet his year's pay, like $15,000, on the game because someone was going to throw the game. So then we might as well, if this guy's so confident, the guy knows something.’ So, we went and gathered all of our money and bet it. (They) ended up winning something like 40 to 10."

"Kevin" did not share a real-life experience like Hunter, but his perspective was that student-athletes might be susceptible to shaving points. He explained that the institution should educate student-athletes:

"I guess I'd warn them about getting to some of the athletes here because let's be honest, it's a smaller conference. Obviously these guys are here to play for their sport; they really don't have too many professional ambitions. So the likelihood of them shaving points, throwing a game, I'd say is actually pretty good. Who doesn't want to make a few extra bucks!"

WHAT'S NEXT?

Otteman presented his dissertation last month to a panel of three professors. They responded with glowing reviews and plan to award him with a doctorate in education, according to the head of the panel. Otteman said he is making minor changes before releasing the study for publication.

The rule

NCAA Bylaw 10.3. Gambling Activities

Staff members of the athletics department of a member institution and student-athletes shall not knowingly:

a. Provide information to individuals involved in organized gambling activities concerning intercollegiate athletics competition.

b. Solicit a bet on any intercollegiate team.

c. Accept a bet on any team representing the institution; or.

d. Participate in any gambling activity that involves intercollegiate athletics or professional athletics, through a bookmaker, a parlay card or any other method employed by organized gambling.

(Revised: 1/9/96, 1/14/97).

Almost a year and a half ago, Otteman set out to study the culture of gambling among college students. He said his research shows that most compulsive gamblers on campus began betting before college, and Lee said he was indoctrinated after he enrolled at Northwestern in 1991.

"There was a guy in the lounge of the dorm," Lee said. "He was watching an NBA playoff game. He was just overly into it. I asked him, 'Why are you into this game so much?' He said, 'I got some money on it.'

"That's how I found out about (sports gambling). My background, gambling is street-corner dice shooting. I didn't know anything about point spreads or anything like that."

Otteman acknowledged there was no way to confirm what the students told him, but said his experience as a gambler led him to believe they told the truth. Josh Moon, who as compliance director at Central Michigan monitors activities that involved NCAA rules, expressed no doubt about the findings.

"The biggest thing was the exchange of information and how that impacts the decisions that gamblers make and how easy it is to get information," Moon said. "It gets back to institutional control. What are you doing to educate people?

“… This is a very serious issue, and it's something you need to continue to address. Not only with the student-athlete population, but to the whole student population."

Through his study, Otteman not only spotlights the problem, but also focuses on solutions.

He is urging Central Michigan and other universities to increase enforcement, bolster campus-wide education and launch anti-gambling campaigns. The NCAA said its support similar measures and points to the online component of the "Don't Bet On It" campaign that can be found at http://web1.ncaa.org/dontBetOnIt/.

But to hear Otteman and the NCAA's Baker discuss the issue, eliminating the exchange of inside information between those connected with college teams and gamblers is a long shot. As for the likelihood of colleges controlling the problem, even if they institute all of Otteman's recommendations, none of the experts are about to post odds.