Global stars taking a pass on worlds

ISTANBUL — Outside the glass windows and a patio dining deck, the Sea of Marmara glistened in the distance. Here, the Russian national basketball coaches could see forever, across a city that connects Europe and the Middle East, across the shore of a city considered to be the bridge between old and new worlds.

Together, David Blatt, the American-Israeli coach, and his assistant, an old Red Army star, Dmitri Shakoulin, bounced between the fragile state of Russian basketball and preparations for their FIBA World Championship quarterfinal game against the United States. Here they were, inside the Champions sports bar connected to this trendy five-star high-rise hotel as though it was one more airport Marriott in Fort Worth or Newark. Chicken fingers and potato skins in the shadows of the Ottoman Empire.

Yes, the world has changed and crass capitalism has come for Russian basketball the way it has everything else.

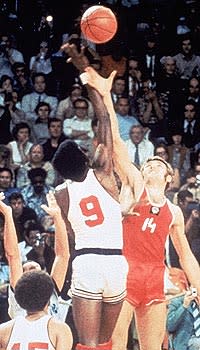

Russia will play the Americans on the 38th anniversary of the most famous international basketball game in history, Russia’s controversial ’72 Olympic gold-medal victory over Team USA. Blatt was 13, watching the game in his Framingham, Mass., home, crying over what he believed to be an injustice. Doug Collins and those scorned U.S. silver medalists won’t like hearing this out of Blatt, an old Princeton point guard, but he’s studied that game in Munich and sees it all differently now.

“Funny things happened, but if you look at it objectively, they were justifiable,” Blatt said. “The commissioner who overruled the referee on two occasions properly did so.”

Blatt is a proud American but sees the world and the game with a far more discerning, critical eye. Whenever Russia is finished in these worlds, Blatt told Yahoo! Sports he will resign as the national coach. Six years ago, Blatt, one of Europe’s most accomplished coaches, was hired to push Russian basketball beyond the cold-war militaristic mindset of coaching which had too grudgingly evolved despite the Westernization of its players. They were millionaires now, and no one embodied that transformation more than its biggest star, the temperamental Utah Jazz diva, Andrei Kirilenko(notes).

“He’s a max contract player in the NBA, making $80 million, and that changed everything for the Russian player,” Blatt said. “Andrei brought Russian basketball to the world stage — and in a user-friendly way. Andrei was a friendly Drago. He had the athleticism, the skill, that people were used to seeing from Americans.

“It’s an enormous responsibility that he took on, but I don’t know if he took it on actively. He carried that torch, but he didn’t carry it to the max. He let the torch start to carry him. In all honesty, Andrei epitomizes what’s going to happen in this whole international competitive environment: These competitions are slowly, surely going to go by the wayside.”

When your nation’s best player is a flake, good luck building a national team around him. AK-47 is no product of a Red Army team, but the spoils of a teenage sensation who got too much, too young. Just like what happens in the United States — and just about everywhere else in basketball now.

Kirilenko comes and goes with the national team, and passed on playing in these world championships. Once, this was the biggest basketball tournament in Europe, but the best players from most of these countries are now sitting it out. When Kirilenko stayed home, so did Russia’s best point guard, J.R. Holden. Blatt needed Holden to handle the USA’s pressure on the ball and needed the wildly skilled Kirilenko to try to match Kevin Durant(notes).

“With them, maybe we have a 1-in-10 chance to beat this U.S. team,” Blatt said. “Without them? Maybe it’s 1 in 100.”

The Americans have the depth of talent to still be the favorite without one single player from the 2008 Olympic gold medalists on their roster. Now, Team USA has a feeder program of young players and a stability that has restored them to the envy of world basketball. More and more, NBA teams are pushing veteran stars to sit out these international events. More and more, rich, young stars don’t want to give up their summer vacations.

As much as ever, the world is influenced by the NBA’s biggest stars. Kobe Bryant(notes) would’ve played had his worn-down body allowed it, but twentysomethings LeBron James(notes), Dwyane Wade(notes) and Chris Paul(notes) will wait until the 2012 Olympics to play for Team USA again.

“I would’ve thought that would give players from other countries even more motivation to play, because you got a chance to beat that [U.S.] team without those guys,” Blatt said. “I mean, if Spain had Pau Gasol(notes) here, they’re the favorite here.”

The Russians bring young players eager to prove themselves on the global stage, and that’s all. Blatt delivered international basketball’s best coaching performance of the past decade with Russia’s ’07 European championship run. But within Russia, it never inspired a revolution to restore the national team.

In the sports bar, Shakoulin, a burly 6-foot-8, sighs and thinks longingly of the good, old days which he knows, deep down, weren’t so good in Russia. In Russia’s Communist past, the sports federation obliterated the bodies of its basketball players with triple practice sessions for weeks and months and years. They would work eight to 10 hours a day, and Shakoulin, 42, has the wrecked knees to prove it. He loves the freedom and opportunities players have today but knows there’s a nationalistic basketball pride eroding and fading away.

“Everybody says that Russia has a lot of patriots, and it’s true, but a player gets a million dollars and he doesn’t want to play,” Shakoulin said. “He doesn’t want to risk injury, or maybe even take the time…”

He pointed to the big television, and the Lithuanians beating the Chinese. All those old breakaway Soviet satellites seem to care so much more about playing for their country. He loves all the newspapers and magazines and websites devoted to the team, the adulation that Lithuanian players are afforded. In Russia, he insists, “The reporters, they just call Kirilenko on the phone and see what he thinks about something. …They don’t build up our team anymore.”

Now, the coaches see a 24-year-old Russian player, Timofey Mozgov(notes) — an unsure 7-footer who has struggled with confidence with the national team — get a $10 million contract from the New York Knicks and they wonder what his motivation will ever be to play for Russia again. All the issues the Americans had 20 years ago, the Russians have now. It was inevitable, and it’s never going away.

“Ah, too much change in my lifetime,” Shakoulin said wearily. “We have two or three different kinds of money in Russia in my life. Too much change.”

All that change, and he loves what Blatt has done for the Russian basketball program. He’ll miss him as coach, he says. Blatt won far more games, developed far more players, than they believed possible with the resources and talent there. Now, he’ll take on the Americans, likely for the final time as Russia’s coach, trying to see if his team can hang around in the game.

Thirty-eight years later, all the hate and acrimony between the Americans and Russians is gone on the basketball court. They used to look across the floor and wonder what in the world they had in common. All those Eastern European states – Serbia, Croatia and Lithuania – gobbled up the best players, and Russian basketball is left fighting for its identity, its soul, its future. Chicken fingers and potato skins in the shadows of the Ottoman Empire and Sea of Marmara — yes, the final victims of American sporting capitalism have paid a steep price.