Why Hard Sends (and Private Islands) Won’t Make You Happy

This article originally appeared on Climbing

Francis Sanzaro’s newest book, The Zen of Climbing, is officially available for purchase. The long anticipated volume dives in to the intersection of climbing and philosophy, discussing the psychological determinants of success and the art of living (and climbing) in the moment. The former editor-in-chief of Rock and Ice, Gym Climber, and Ascent has been climbing for more than 3o years. His first book, The Boulder: A Philosophy for Bouldering, received critical acclaim and is now in its second edition. The Zen of Climbing is available on Amazon and at Barns and Noble. Enjoy the three excerpted chapters below and stay tuned for a review.

***

The Summit

It is at the top where you find the bottom.

I remember watching a TV show about a billionaire who developed his own private island near New York, adjacent to Manhattan. It took him years of painstaking work to build. He spared no expense. Then he finished it. Standing there, on film, pondering the sea and his new home, said he had expected to have great thoughts on his private island. But, after the last construction worker left the site, it turned out nothing had changed. He still had the same old thoughts. After a few months, he sold the place. He looked sad. He had expected so much.

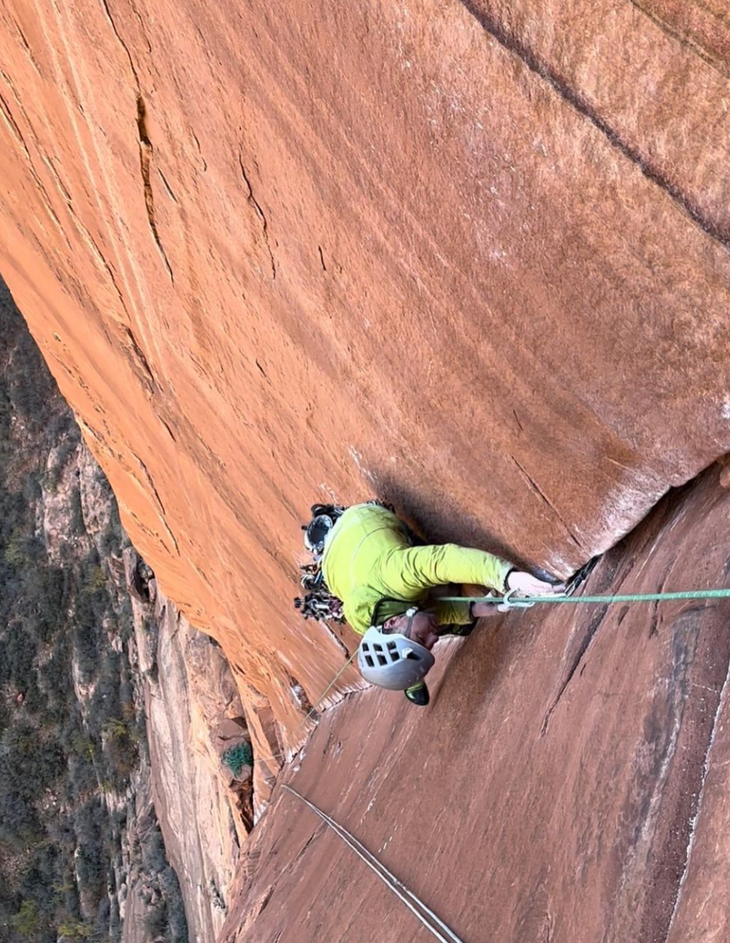

We're lucky as climbers. The places we go are inspiring, the stuff of billboards and multi-million-dollar commercials--desert towers, ribbons of ice, soaring ridges and cliffs of blue limestone. The climber's terrain is idealized, given the romanticization of the summit. As far as nature is concerned, the Western imagination is 'topophilic' (in love with place). The earliest goals in climbing--in the 1800s and first half of the 1900s--were predominantly those of being the first to stand on top of something. Such was the case for Mont Blanc, the Matterhorn, then into Alaska, the Himalayas. Climbers were "conquerors," and the visual iconography in that time was one of a general marching into battle along with his soldiers (and porters). Then, after most peaks were topped out, alpine climbing moved to more technical faces while, starting in the 1970s, rock climbers and boulderers found difficulty as a reward. In America in the 1950s and '60s, however, John Gill's focus on form and inner feeling was an exception. Gill, with a modest background in gymnastics, viewed climbing, and especially bouldering, more in terms of gymnastics than anything else. For Gill, grace in execution was paramount.

The top is a legacy of climber-thought, drawn from our deep history, popular imagination and our own romantic leanings that overcoming difficulty, and hence, achieving a new level, is the main goal. The problem is that climbing is equally expressive--a dancer would not go to the studio and consider it a good day if they only did a hard sequence, as if, once they had done it, they could move on to another hard sequence. A dancer wants to feel flow. A dancer wants to be in it. The dancer wants to become the dance, to merge with their body. A dancer chases a feeling, a state of bodily affairs. Ueli Steck, the late Swiss alpinist and holder of multiple speed records up the most dangerous alpine faces in the world, including the North Face of the Eiger, once said: "Mountaineering is a transient experience. I need to continuously repeat it to live it." Steck is right. Doing a difficult alpine climb is satisfying, but it's a label post-performance, and, hence, a dull concept we apply to something beautiful and timeless. We too build our private islands--visions of success--and we convince ourselves that once we achieve it, we'll be like the billionaire. We'll stand on the shores of our hard sends and be different people, have better thoughts. But that's never the case. We are chasing ghosts. It is better to go into a hard project, or trip, convincing yourself that doing such and such a route will not change a thing about you, or your life. Do that with climbing, and your trip changes. For the better. Do it with the rest of life, and you are starting to taste Zen.

Copyright on Enjoyment

The art of a mindful body is the art of elite athletics.

Elite climbers are no more satisfied with their sport, nor do they enjoy it more, than average climbers. A pro surfer has no more fun than an average one. But there is a caveat: a seasoned athlete embodies the possibility of deeper affects as a result of their trained body, which can lead to a richer, more meaningful experience.

When you have muscle and neural memory in certain movement patterns, the body provides a potpourri of sensation a beginner does not have access to--namely, climbing gracefully creates pleasant sensations in the body that climbing clumsily does not. Give a beginner a javelin, tell them to toss it, and their focus will be on gripping the thing and trying to throw it as far as possible. Throwing the thing won't feel very beautiful. Their minds are riveted to base execution. Their bandwidth of attention is taken up by the mechanical complexities of completing the task. As for climbers, a beginner applies too much strength at the wrong time, ignores their footing, overgrips, undergrips: a sense of awareness in and of the movement is inaccessible. They are overthinking it. Underthinking it. A first-time javelin thrower might like it, but they don't experience deep joy in tossing it. Give the javelin to an expert, and they will also concentrate on execution, but their bodies know the basics, which loosens attentional space for a deeper engagement with the movement, like being able to watch a beautiful film without having to take notes. Because it is an experience, and all experience has shallow and deep forms of engagement. All athletic movement has levels of engagement as well. It is this deeper engagement that builds craft, practice and mastery. Top athletes in any sport are able to apply no more, nor less attention than is needed. This is the age-old formula for your own quest to be a better athlete.

To borrow a term from critical theory, a seasoned athlete is more affective, affect defined as potentiality to feel, a state of being receptive to the energies the body and world provide. Affect is a pre-verbal possibility in which we can be moved. Affects are not feelings or emotions but indicators of our ability to be moved by the former. Top athletes have the potential to be deeply affected by movement because of their psychosomatic investment in a specific set of movement patterns. Movement is memory, and memory spans the spectrum of cognitive functions because it is the inter-connective tissue of temporality: memory spans time like nothing else can. Movement for seasoned athletes is an echo chamber where previous movements come alive, where they interact with the present, where they built the future. Where they analyze, compare, get drawn into the well of the body's deep psychosomatic history. It's just a fact of movement that athletes move with deep history in their muscles, thought patterns and tendons. Muscles produce feelings. Doing something well is not just a concept we give to ourselves, such as "It sure feels good to be good," and that's the reward. Rather, it is autotelic, which means the purpose of doing something well is sufficient unto itself. The reward is in the moment, and, for that reason, a concept cannot capture it.

Erasing Art

The art of erasure ensures that creative perception is highest priority.

American poet and artist Jim Dine put on retreats and clinics. At the end of each day, he told his students to erase what they have done. The students are always shocked, if not offended. They look at him weirdly. They hesitate.

Did he say what I think he said?

They are puzzled.

WTF?

They look at each other.

This is my best work.

This is what I paid for.

Yes, he did say that.

Erase it all.

With great reluctance, the students erase eight to twelve hours of hard work in seconds. After a few days of working and erasing, however, Dine has made his point--most artists are too attached to the outcome and not enough on drawing. His first point: when you are figure drawing, what matters is looking, looking carefully and patiently, and not caring what the result looks like because if you look carefully enough, the result takes care of itself. And another thing happens: the act of looking becomes the priority, and hence, you become a better artist because you are a better "looker." Riveted attention to the task is the goal. His second point, implied in the first, is that it is natural to be future-oriented and let attachment take hold. We often default to that position. After you have internalized the art of looking, only then, at least in terms of realistic drawing, can you take liberties in attention, that is, you can (like an expert javelin thrower) explore style in the execution. This happens because you have the bandwidth.

The history of Zen art testifies to the power of internal awareness, because listening is subtracting. Clearing the mind from any preconceived notion of what you think you need to paint allows that perfect moment when the brush brushes itself. D.T. Suzuki wrote of Zen art, "Technical knowledge is not enough. One must transcend techniques so that the art becomes an artless art, growing out of the unconscious." Calligraphy, of which Zen art has a long history, seeks that moment when the artist's arms and hands move without cognitive distraction, and it is said it can take a lifetime just to perform the simple task.

As a climber, when you start 'erasing' like one of Dine's students, you need to develop deep patience. It can take years, but the payoff is tremendous. In place of thinking that you will either succeed or not, always a very imprecise way of thinking, awareness needs to be on the only thing that matters--execution. Strategy is execution as well, but to pull that off, you need your base layer of execution to be seamless. In his process of doing the world's second V17/9a at Red Rocks, the Colorado-based climber Daniel Woods described to me in an interview how he had to learn the art of erasure, of removing attachment from the outcome: "At first I was too consumed about the send, rather than just flowing with the move, like taking it move by move and focusing on my breath…and I'd be like, man, this could be the one or this could be the one, you know, I was too. I was too focused on the send rather than being present. And I had, like, we had probably a week and a half where I just had that feeling. And then suddenly, I just had to flip my head and be like, look like, every, every day now is just a session, we're going to start and just see how far we can get. I think I just told myself every time to just see how far you can go, like, create, like, focus on your flow, focus on your breath. Like, create a good rhythm and have fun on it. You know, like, you're climbing on a line that has sick moves. It's hard. It's challenging, but just have fun, you know. And when I started getting into that mentality, all that pressure kind of vanished, and I just, I was climbing better on it." Wood's experience grew because he took away.

Also by the Author:

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.