Unsolved mystery: Ray Lewis returns to Atlanta

ATLANTA — The chalked V that marked the spot where one man died and another was mortally wounded on a Buckhead street on Jan. 31, 2000, is long gone. So are the bloodstains that dotted the street and the gutter beside it. The lounge two blocks up the road was demolished years ago. There’s not much left in Atlanta still standing from that night except the questions and the suspicion.

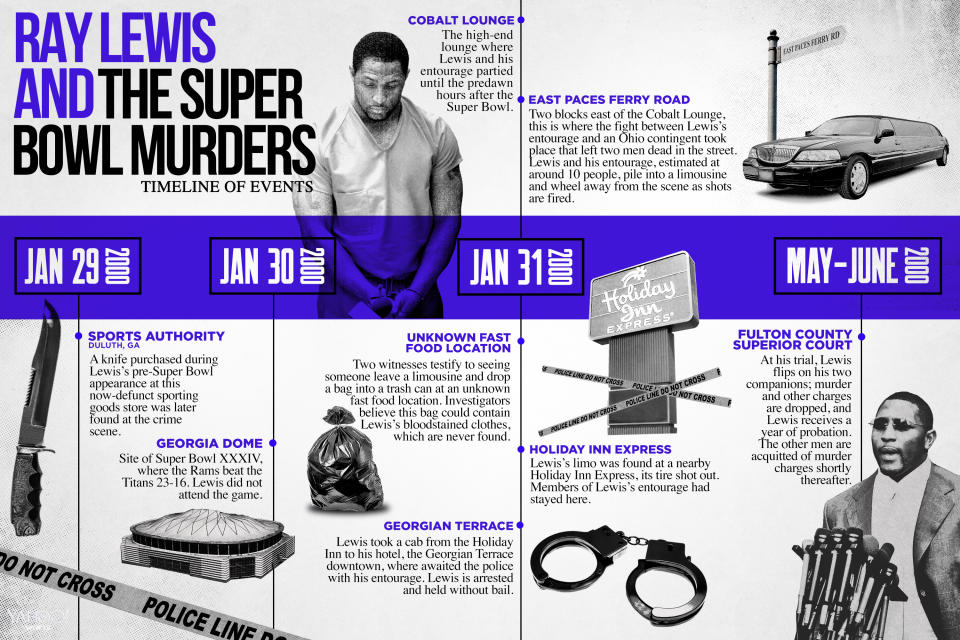

In the early morning hours after Super Bowl XXXIV, as St. Louis Rams fans celebrated a 1-yard victory over the Tennessee Titans in Atlanta’s Georgia Dome, a fight broke out in a nearby nightclub. When it was over, two men lay dead in the street, and another lives under a perpetual cloud of suspicion to this day.

Ray Lewis has achieved greatness by any measure. He’s a Super Bowl champion and MVP, a Hall of Famer, a charismatic speaker, an inspirational force of nature. And he’s also forever defined by that single night in Buckhead — which to a large extent is fair and right.

Thursday marks the 19th anniversary of that night, as well as the 19th anniversary of the last time the Super Bowl was held in Atlanta. And now, just as the Super Bowl has returned to Atlanta, so too has Lewis. He’s hosting a party Friday night for the “Ray of Hope” charitable foundation, questions from that night still trailing in his wake.

What happened with Ray Lewis in the early morning hours after the Super Bowl? What aspects of the story have gotten obscured over time? How much has Lewis sanded off the edges of the story to burnish his own reputation? And for a hot-take, reputation-obsessed culture, here’s the toughest question of all: How much more does Ray Lewis have to pay for what happened that night?

Jan. 31, 2000

Here are the facts: Ray Lewis was involved in a fight that ended in the stabbing deaths of two men. Lewis didn’t kill the men, not in the eyes of the law or in the recollections of witnesses. He didn’t even throw a punch. He did obstruct justice. He did lie to police. He did associate with the kinds of people who get in fights where people end up dead. He did flip on those same people, pleading guilty to a misdemeanor charge. And he does remain active in the public eye, even as questions about what happened early in the morning of Jan. 31, 2000, continue to follow his every move.

Lewis at the time was a young star with the Ravens, a monster of a linebacker who embodied the team’s ferocious defensive intensity. The weekend of the Super Bowl, he rented a limousine – at a cost of $3,000 per day – and traveled to Atlanta to enjoy the spectacle. Among those accompanying him were Reginald Oakley and Joseph Sweeting.

Before the Super Bowl, Lewis made an appearance at a Sports Authority in Gwinnett County, north of the city. While Lewis signed autographs, Sweeting, Oakley and a third member of Lewis’ entourage purchased knives. A signature identified as Lewis’ was found on the receipt for the knives.

Lewis and Sweeting didn’t attend the Super Bowl, but Oakley did, and saw one of the great endings in NFL history. The Titans fell 1 yard short of possibly tying the game, as Kevin Dyson was tackled within mere feet of the end zone, and the Rams celebrated in what is, to date, their most recent Super Bowl title.

[Ditch the pen and paper on football’s biggest day. Go digital with Squares Pick’em!]

It was a thrilling end to what had otherwise been a debacle in Atlanta. Transportation woes had paralyzed much of downtown, and a freak ice storm threw the unprepared Southern city into a panic. It has taken 19 years and a new stadium for the Super Bowl to return.

In the hours after the game, Oakley reunited with Lewis and Sweeting, and the entourage set up camp at Cobalt Lounge on East Paces Ferry in Buckhead, one of the finer high-end clubs in the city. Michael Jordan and Wayne Gretzky had passed through its doors during the week, and the club had a rep as a see-and-be-seen spot for celebrities.

Lewis and his crew avoided the traditional sectioned-off VIP section, instead posting up near the front door and mingling with the 400-person crowd. Lewis, wearing a fur coat and a $45,000 necklace, had paid the doorman to let him and his people inside, and he was reveling in the attention.

“All that jewelry, plus my mink coat, I must have been wearing about a quarter-million dollars, but those were heady times, man,” Lewis wrote in his autobiography. “This was how we rolled, me and my boys, and when you come from nothing like I did, step into all this money like I did, you’re bound to strut a little bit.”

The fight

Somewhere around 3:30 a.m., a good five hours after the game had ended, Lewis and his group – a total of six men and four women – began walking east on East Paces Ferry to get back in the Lincoln Navigator limo. And that’s when everything went south. A group of men from Akron, Ohio, including two men named Richard Lollar and Jacinth Baker, began arguing with members of Lewis’ entourage.

“Man, f – – – Ray Lewis!” one said, according to Lewis. “Kill that n – – – -, dawg!”

As the situation grew more heated, Lewis says he shoved Oakley into the limo, attempting to defuse the situation. But Oakley leaped out of the limo, and that’s when everything exploded. Baker smashed a champagne bottle over Oakley’s head – this is one of the few elements of the night that all parties agree on – and chaos erupted.

Some witnesses said two men dragged Sweeting to the ground and began beating him. Others said they saw Oakley chase down Baker. Lewis and the rest of the men piled back into the limo, which wheeled off as one of the victims’ friends began firing a gun at the departing vehicle.

At some point along this drive, the limo stopped at a still-unidentified fast food location and an individual got out of the car and dumped a bag – one witness called it a hotel laundry bag, another a brown paper bag – in a trash bin. Prosecutors would later contend that this bag contained Lewis’ clothes, presumably a white suit, which has never been located.

Back at the scene, both Lollar and Baker lay dead. Investigators found a small folding knife near the bodies; the knife is traced back to the Sports Authority in Gwinnett.

The limo, its tire flattened from the gunshot, stopped at a Holiday Inn Express about a mile from Buckhead, and Lewis took a cab from there to the Georgian Terrace hotel downtown.

“Nobody thought to call the police – not because we had anything to hide, but because there was nothing to say,” Lewis would later write. “Where I come from, you don’t call the police, tell them shots were fired, until you know the deal.”

The deal became obvious as soon as Lewis and his entourage gathered to watch news coverage of the incident. When the newscast revealed that two men had died, tempers in the room flared.

“Did you stab anyone?” Lewis asked Oakley, as Oakley would recall later. Lewis then ordered everyone to keep quiet – this is where the obstruction-of-justice charge would begin – and held his head in his hands.

“I’m not trying to end my career like this,” he said, according to later court testimony.

The arrest and court case

Detectives found the limo driver changing his blown tire and began questioning him. They would meet with Lewis at his girlfriend’s home in Atlanta. And by nightfall on Jan. 31, after an interview in which Lewis gave several misleading statements, the police had Ray Lewis in custody. The charge: murder.

Blinded by Lewis’ superstar status, Fulton County prosecutors opted to go all-in, charging him with murder even though police investigators wanted to pursue a more conservative approach. It’s worth noting that Georgia law indicates “any party who did not directly commit the crime may be convicted for the commission of the crime upon proof that the crime was committed and that he was a party thereto, despite the outcome of the one who directly committed the crime.” Even so, this was a long-shot gamble for the prosecution.

On Feb. 10, 2000, then-Atlanta Mayor Bill Campbell, Fulton County district attorney Paul Howard, and an array of police leaders announced they would seek a murder indictment against Lewis. That proved to be a crucial mistake.

“I don’t think Ray Lewis ever should have been charged with murder,” Ken Allen, then an Atlanta homicide detective, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2013. “I don’t think he committed a murder. He would not have stabbed anybody. He had no reason to stab anybody.”

Still, two days later, Lewis, Oakley and Sweeting – the latter two of whom were still at large – were indicted on two counts apiece of malice murder, felony murder and aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. Sweeting and Oakley turned themselves in as Lewis was released on a $1 million bond.

Jury selection began on May 15, 2000, and by May 22, a jury of nine black women, one black man and one white woman was empaneled. The trial began on May 23 and didn’t take long to go sideways for the prosecution.

The evidence didn’t support a Ray Lewis murder charge; Lewis’ expensive attorneys had little trouble blowing the city’s case to pieces by destroying witness credibility. Combine that with the fact that Howard wanted to try the case himself despite not having recent trial experience, plus the way the state’s key witnesses seemed to have an elastic relationship with truth, and the result was a debacle for the prosecution.

One after another, the state’s witnesses collapsed under the weight of defense scrutiny:

– Jeff Gwen, who had been with the victims, told police on the night of the incident that he saw Lewis punching Lollar. But under oath, he reduced his characterization of their fight to “tussling.”

– Duane Fassett, the limo driver, had said on the night of the incident that he saw Lewis punch one victim, and heard Oakley and Sweeting tell each other, “I stabbed mine.” But on the stand, Fassett walked both statements back, saying he never saw Lewis throw a punch, and did not remember what he heard Oakley and Sweeting say.

– Chester Anderson, a witness to the fight, testified that he saw Lewis kicking a victim lying face-down on the street. But cross-examination broke down Anderson as an identity thief who bought cars under false names, and the defense flew in the man whose name Anderson had stolen for a dramatic “stand up” moment.

That was enough for the prosecution to realize that the Lewis case was a lost cause. Howard called an audible, getting Lewis to flip on Oakley and Sweeting in exchange for only a misdemeanor charge of obstructing justice.

Lewis testified that he saw both men in the middle of the fight, and added that he saw a knife in Sweeting’s hand. But he also helped the defense’s case of self-defense by noting that the victims’ group had attacked Sweeting and Oakley.

The jury returned a verdict of not guilty for both Sweeting and Oakley, who celebrated their freedom at another now-vanished Atlanta institution: the Gold Club.

Lewis returned to the field, and although he was fined $250,000 by the NFL, he led the Ravens to a Super Bowl victory the very next season. He continued to play until the 2012 season, when he retired after a second Super Bowl victory. He was sued by the families of both victims, and reached undisclosed settlements with both.

“I had no hand in their deaths, I could not ease the suffering of those families,” Lewis would write. “But I had so many blessings in my life, I told myself I could use some of those blessings for these good people. They were hurting. I was hurting. It was not an admission of guilt – it was an expression of love, of sympathy. I gave because I had it to give.”

What came next

Since retirement, Lewis remains very much in the public eye, preaching a message that ranges from inspirational to incomprehensible. When he speaks on Buckhead – and it’s not often – he does so in oblique ways, and always brings it back to his own suffering … and, of course, triumph.

Speaking at his Hall of Fame induction ceremony, he noted, “1999 to 2001 may have been some of the darkest moments of my life. But I’ll tell you something: When God says, ‘Can you hear me now?’ he sends you a family to make sure you’re OK while you’re going through what you’re going through.”

His common theme these days is a specific kind of togetherness, one that respects authority while leaving room for inspirational fist-pumping.

The slayings also effectively shut down Buckhead’s nightlife. Only a few years earlier, the city of Atlanta had cracked down on Freaknik, a spring break festival of historically black colleges that effectively paralyzed the city for an entire week in April. Buckhead had taken that party-till-dawn mantra and turned it into a year-round ethos by the time of the 2000 Super Bowl.

Even before that weekend, Buckhead residents had been fighting for earlier last call and fewer bar permits. But the killings gave the stop-Buckhead movement momentum, and police crackdowns for minor violations helped snuff out the last of the area’s party rep.

The Cobalt Lounge, where it all began, has been torn down and built over, as has the brick condo where residents watched the fight on East Paces Ferry Road. The Sports Authority where the knives were bought is now a Sam’s Club. The Georgia Dome, site of that Rams-Titans Super Bowl, was demolished in 2017.

Questions still remain about the killings. Who stabbed Baker and Lollar? While Lewis wasn’t holding the knife, someone obviously was. Did they use it in self-defense? Were they provoked? What was really said in that limo? What happened to Lewis’ suit? How much does Lewis know that he still hasn’t revealed?

Because of those questions, Lewis remains eyed with suspicion despite the weight of available evidence and the county’s plea bargain. In the eyes of the law, Lewis is guilty only of a misdemeanor, and he long ago paid off that debt. Here’s the question that will follow him the rest of his days: How much should America continue to hold him accountable for that night?

It’s indisputable that Lewis had something to do with a fight that ended in the deaths of two men. Whether his role was instigator, perpetrator or peacemaker, he was involved in a crime. He’ll never outrun that one terrible night. But Fulton County made one decision about his guilt. Much of the public has made another.

More from Yahoo Sports:

• NFL commissioner breaks silence on blown no-call

• Did Saints coach take a shot at Goodell with his T-shirt?

• TV station worker fired for label on Pats’ Brady

• Wetzel: Browns QB turned the tables on all the doubters