Tracing history: Inside the rich, thrill-seeking life of Elias Bowie, a pioneer among Black NASCAR drivers

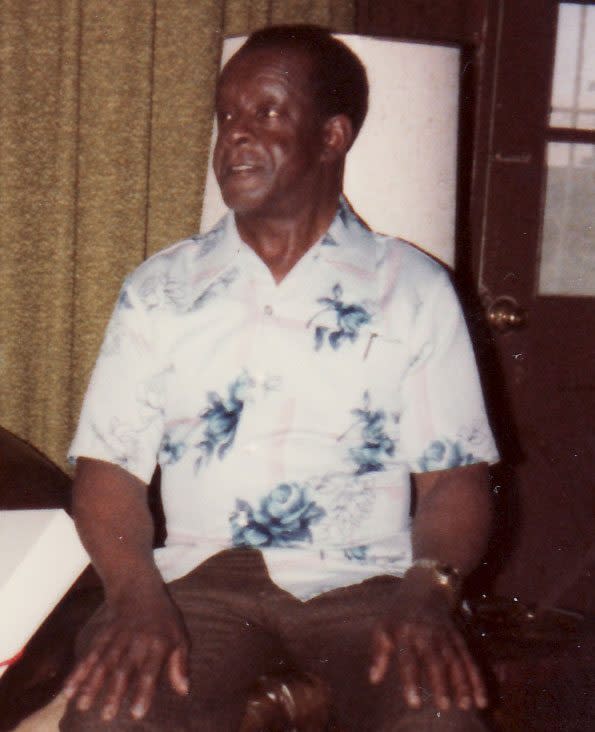

Craig Manson has always been fascinated with his great uncle Elias Bowie. Pronounced like buoy (read: not like the car crazy rock god), Bowie was the star in the family, the larger-than-life character who pulled up to gatherings in beautiful Cadillac cars and stepped out dressed head-to-toe in his Sunday finest. Some of Manson‘s fondest memories of growing up in the ’50s are of granduncle regaling him with tales of his adventures in and around the Bay Area, where Bowie ran a variety of transportation businesses.

“He loved to speed, he loved his Cadillacs and he loved wearing his fedora,” says 68-year-old Manson — a retired lawyer, judge and professor. And yet he couldn‘t help thinking that there was so much more to his great uncle’s story that Bowie had left out.

Manson‘s suspicions were finally confirmed in 2006, a year after Bowie‘s death at 94. While fact-finding for an extensive family genealogy project, Manson stumbled upon an Aug. 1, 1955, article in the San Mateo (Calif.) Times about a stock-car race that had taken place over the prior weekend at Bay Meadows Speedway — a mile-long dirt oval that opened as a horse racing facility in 1934, and where NASCAR raced on the same track as the ponies.

Lee Petty, Marvin Panch and Buck Baker were just a few of the NASCAR luminaries who started the 250-lap Grand National feature. In the end Tim Flock took the checkers ahead of 33 cars in front of 15,000 spectators. Finishing in 28th place was Bowie, Manson‘s father‘s uncle. It might not have seemed like much of a result on paper at the time, but its discovery years later would rewrite NASCAR history.

Bowie, you see, was Black. And by finishing that race in San Mateo, that technically makes Bowie six months earlier to NASCAR than Charlie Scott — the man long believed to have been the first Black driver to start a Cup race.

Manson‘s discovery does less to correct matters than provide clarity.

“It‘s really hard to trace some of that early history of African-American drivers,” says NASCAR historian Ken Martin. “In the first decade or so, a lot of drivers would just show up for one race, and there was no check mark on the entry for your race or ethnicity.”

MORE: NASCAR Diversity

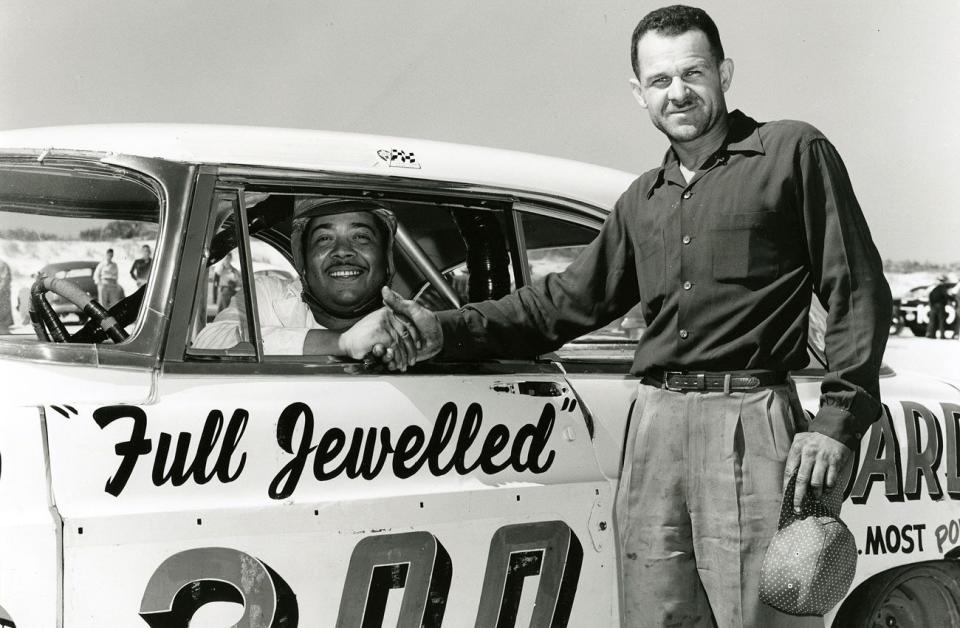

Scott was a typical one-off. He entered the 1956 road-course race on Daytona Beach with Carl Kiekhaefer‘s powerhouse outfit as one of their six drivers and finished 19th after qualifying five spots higher. That same day Charlie Scott is photographed shaking hands with Wendell Scott (no relation) — the Cup Series mainstay who is rightly recognized as stock-car racing‘s Jackie Robinson.

And while the photo predates Wendell‘s official NASCAR debut in 1961, the Scott family contends Wendell‘s career actually started in the late 1940s on short tracks in Virginia and the Carolinas.

“Wendell was already racing all over the South, winning state championships, sportsman championships and things like that,” Martin says. “He was already making a name for himself. He just hadn‘t moved up to the Cup Series yet. You never know what that time with Charlie may have meant to Wendell and how he went ahead and developed his career a few years later.”

Manson, though, isn‘t interested as much in debating history as he is marking his great uncle’s place in it. Bowie’s race was just the second Grand National event ever held at Bay Meadows, far more famous as a horse-racing venue. “Back in that period,” says Martin, “they‘d race just about anywhere — at fairgrounds, on the beach, on a dirt road course at Willow Springs. The sport was just growing, and it was finding a place to compete.”

Bowie really soaked up his moment in the spotlight. According to legendary promoter Ken Clapp, Bowie and his team drove to the track in their Cadillac race car — removing the back seats, taping the headlights and adding a number in the pits. The San Mateo paper credits Bowie with bringing the largest pit crew, which reportedly included “a lanky double-jointed chap in a green fatigue uniform.” It also notes that he finished the race on a single tank of fuel. No doubt the incredible mileage was helped by a slew of yellow flags for accidents — none more spectacular than the single car that flipped into a turn after a tire came loose.

Even though Bowie survived the afternoon unscathed, like Charlie Scott, he never entered another NASCAR race. It‘s a shame. Manson says Bowie fell in love with driving as a teen coming of age on the Texas Gulf Coast in the 1930s. There, he worked as an indentured servant to a white family, cooking and driving. After serving in World War II with the Army, Bowie worked odd jobs to finance his dream of building a chauffeur and transportation empire. In the 1960s he landed at a San Francisco gas station, taking over the joint after about four years. He‘d parlay that small fortune into a jitney business running fares up and down Market Street. “I can‘t remember how long of a ride that was back then,” Manson says, “but my job one summer was to collect a dime from every rider.”

That success eventually spawned a cab company that covered San Francisco called King Cab, named in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King. “Cab medallions were really expensive,” Manson notes. “But he somehow got in with the mayor and got a deal, I don‘t know how. But I did come across an article just the other day where a columnist in the San Francisco paper was criticizing the mayor because of some shady dealings in the medallion business.”

Before long, he added a sister company in San Jose that Manson‘s parents ran while juggling full-time jobs. All the while Bowie reveled in success, lavishing bride Cleola on San Francisco‘s Baker Street and buying himself Cadillacs to match. Often, Manson and his family traveled from their New Mexico home to visit Bowie — whom he remembers as garrulous, jovial and warm.

Bowie‘s can-do spirit clearly had an impact on Manson — who, among other legal gigs, served as assistant secretary of the interior under President George W. Bush. If Bowie and his kinfolk seem intent on making a way in spaces that weren‘t necessarily geared for them, it‘s because trailblazing is in the blood. Prominent among their ancestors is James Bowie, a Louisiana free man who owned property at a time when Black Americans were still enslaved.

More than a century later Bowie would seek out his freedom on the open road, usually behind the wheel of a big Cadillac. His speedy road trips to and from Reno, Nevada, casinos were notorious in the family. “Sometimes on the way back,” says Manson, “his tickets would exceed his winnings.”

When San Francisco drew New York in the 1962 World Series, Bowie drove cross-country to take in a few games at Yankee Stadium. Bowie was doing Cannonball Runs before Burt Reynolds and the gang enshrined those races into car culture lore.

Growing up in New Mexico, Manson regarded Bowie like something out of a Dick Tracy comic. When he found out that there was indeed more to the story, he published a blog post with his findings. Ultimately, his story landed on the radar of motorsports journalist Rebecca Gladden. And it was through her reporting that Bowie‘s tale reached NASCAR.

Likely, where Bowie slots into NASCAR‘s official history will remain an ongoing discussion. That Manson was able to prove some small part was played by his great uncle — who, despite all his talkativeness, never mentioned his on-track exploits to family — is a victory in and of itself.

“It means quite a bit,” Manson says of Bowie‘s recognition. “For one thing, given the history of NASCAR, I‘m really glad that they have recognized all the early African-American drivers, including Wendell Scott and Bubba Wallace now. Even though my granduncle didn‘t really do a lot in the sport, he was the first. As a lawyer I appreciate accuracy.

“I know if Elias Bowie were around, he‘d appreciate it very much also.”