'State of shock:’ Canceled bowl games bring disorder to fans, teams, finances and TV

SAN DIEGO — About 28 hours before kickoff this week at the Military Bowl, Steve Beck was reviewing game-day plans at a meeting in the nation’s capital when he was summoned to leave the room to hear some bad news.

Boston College couldn’t play in the game against East Carolina after getting hit with an outbreak of COVID-19.

Beck, the game’s executive director, then walked back into the meeting and announced the Military Bowl was canceled, depressing a conference room that included officials from both teams, ESPN and stadium operations.

"Everybody was in like a state of shock,” said Beck, whose game was canceled for the second straight year. “Just an hour earlier, we heard everything was OK.”

Last year, 19 college football bowl games got canceled amid the COVID-19 pandemic, all before teams arrived in the cities of the games. This year, five games have been canceled so far because of the pandemic, including four that left teams and their fans at least temporarily stranded after considerable travel expenses.

The fallout this time might be even more painful in certain ways compared last year. This year, some fans spent more than $1,000 on travel costs before being locked out of their canceled bowl. One coach said he “felt lied to” after his game was called off about five hours before kickoff. Television networks also had to settle for less attractive replacement programming on much shorter notice, especially ESPN, which aired six straight episodes of Peyton’s Place after the Hawaii Bowl was canceled less than 24 hours before kickoff.

WATCHABILITY RANKINGS: What's worth watching on New Year's Eve, New Year's Day?

Here's a snapshot of how it unfolded for various parties as the College Football Playoff starts Friday and could be similarly impacted by the spread of the omicron variant:

'Weird’ situation in Hawaii

Even though the Hawaii Bowl was canceled, Memphis head coach Ryan Silverfield presented his team with the Hawaii Bowl trophy at a team meeting in Hawaii on the morning of Dec. 24, the day the game was supposed to be played. His team was scheduled to play Hawaii, which withdrew from the game citing a recent surge of COVID-19.

The trophy will be put in the team’s recruiting lounge along with other bowl trophies, athletics department spokesman Scott Burns said.

“Disappointed we weren’t able to play the game, but we are bowl champions,” Silverfield said at a news conference in Hawaii. “That’s the one thing I told them, that it was the most important thing that we go home with this trophy and rightfully so. Those players, those seniors, earned the right to be called champions because they did everything the right way.”

Players instead treated game day as a day off and went to the beach.

But it doesn’t count as a forfeit win for Memphis because the game was considered a “no contest,” Memphis athletics director Laird Veatch explained in a letter to Memphis supporters.

“So we're Bowl champions but finish the season 6-6,” he wrote. “Weird, I know. These are strange times.”

By contrast, the Playoff semifinals on Friday will be treated differently. An unavailable team shall forfeit the game and its opponent would advance to the national championship game, according to the Playoff.

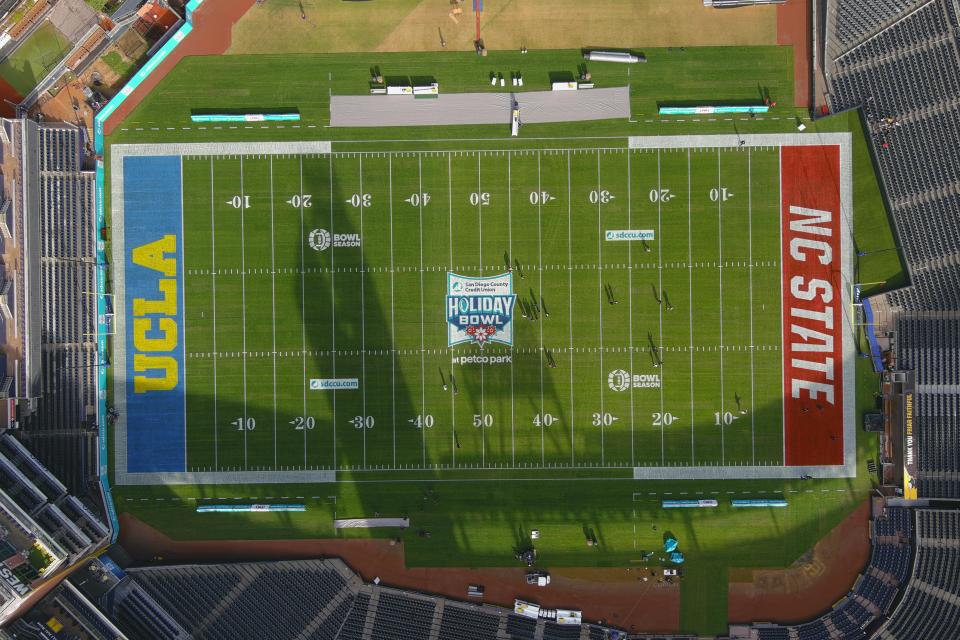

Stranded in San Diego

On Tuesday evening when the Holiday Bowl was scheduled to be played in San Diego, fans from UCLA and North Carolina State wandered around the rain-dampened streets outside Petco Park trying to figure out what to do.

The lights were on inside the stadium. But there was no one home. The game had been canceled about five hours before kickoff because of a COVID-19 issues with UCLA.

“It puts a damper on everything, especially the kids,” said Linwood Sheridan, who traveled from Raleigh, North Carolina and spent about $1,400 for the trip. “We came from miles away, with delays and travel expenses and all that, but we’ll still get a vacation in.”

DAN WOLKEN: Here's why the College Football Playoff is finally primed for a surprise

Sheridan and Denise Harper, a fellow Wolfpack fan, instead took pictures of Petco Park from outside the locked gates and tried to get in some sightseeing before their flights back home the next day. Several UCLA fans filled into Bub’s, a nearby restaurant and bar, where television screens showed the Liberty Bowl instead.

“I had decided even if it had been canceled prior to my coming, my hotel and my airfare were not refundable, so I was coming whether they played the game or not,” said Harper, who spent less than $1,000 on travel from North Carolina. “It’s frustrating. It’s disappointing. But I have had come anyway and spent more time sightseeing.”

Both Sheridan and Harper still said they had a good time in San Diego after arriving the day before.

But North Carolina State coach Dave Doeren had a different perspective. He said he “felt lied to" and “felt like UCLA probably knew something was going on with their team and didn't tell anyone on our side.”

N.C. State receiver Porter Rooks went on Twitter Tuesday and posted his own displeasure.

“Gonna cancel 5 hours before the kick?!” he wrote. “Spent Christmas away from home, practiced for a month, had family fly across the country to watch the game.. smdh”

Gonna cancel 5 hours before the kick?! Spent Christmas away from home, practiced for a month, had family fly across the country to watch the game.. smdh

— Porter Rooks (@Porter_Rooks) December 28, 2021

Plan B for TV

Disney-owned ESPN and ABC have made a big investment in bowl games and are the money machine that drives the system. They were scheduled to televise all but three of 44 postseason games, including the national championship and Celebration Bowl of the Football Championship Subdivision. ESPN Events even owns 18 minor bowl games, showing off a sound bet.

Such games often draw around a million viewers, typically much more than what network rivals are attracting at those times. But when the games are canceled just hours or days before kickoff, networks are forced to fill the time with content that is likely to draw a much smaller audience, disappointing advertisers.

See salaries for college football coaches through the years

For example, Fox was supposed to televise the Holiday Bowl but ended up showing a “Fox Winter Preview” of upcoming shows to help fill some of the void during what would have been the second half of the game.

After the Military Bowl was canceled a day before kickoff, ESPN replaced some of the time slot with “This Just In – Max Effort” with Max Kellerman. It also moved NFL Rewind and NFL Live over from ESPN2.

Last year, bowl games were canceled with more notice: eight before December and none less than two days before kickoff. This year, the Hawaii, Military, Holiday, Fenway and Arizona bowls all were canceled with four days of kickoff, including three the day before or day of kickoff. Two other bowls nearly were canceled but found replacement teams to save the day – the Sun and Gator bowls.

ESPN declined to discuss the financial impact of cancellations. But networks generally don’t expect to pay for broadcast rights for games that aren’t broadcasted.

“It would be great if they did,” Beck told USA TODAY Sports with a laugh.

In turn, bowl organizations generally don’t expect to provide payouts to teams and their conferences if the game isn’t played. After being canceled last year, Beck said the Military Bowl did not provide payouts, which in recent years have been about $1 million per team.

Unlike last year, this year teams traveled to games that didn't happen. Liability for those expenses could be subject to debate. Several conferences and bowl games didn't return messages seeking comment about the status of payouts from canceled games. Beck said he assumed that no game means no payout but he hadn't discussed it yet with his conference partners.

Money matters

Without that revenue, teams and their leagues must find other ways to cover travel expenses. East Carolina and Boston College both made the trip to the Washington, D.C., area before the game in Annapolis, Maryland was called off. ECU set up a bowl fund for donations to cover expenses.

“Bill Clark Homes made a substantial lead gift of $200,000 to cover bowl rings for the football team and remaining funds will be applied toward bowl expenses,” the school said in a release.

Veatch, the Memphis athletics director, noted that mid- and lower-tier bowl games “cost more than they bring in” but that the Tigers’ American Athletic Conference covered the cost of the charter flight to the Hawaii Bowl. In general, payouts from bowl games go to a team’s conference, which then shares that and other collective revenue with all members.

Veatch also suggested he expected ESPN to help with expenses as the game’s owner.

“We fully anticipate that ESPN and the AAC will fulfill those obligations, since we were fully prepared to fulfill ours,” Veatch said in his letter to supporters.

Besides teams and leagues, bowl games are individual businesses that suffer from cancellations. Many are nonprofit operations that promote tourism to their regions. By contrast, the Military Bowl’s mission is unique in that it benefits the nation’s current and former service members. It hopes to persuade those who bought sponsorships or tickets to donate those purchases toward that cause instead of asking for refunds, like many fans have for other canceled games.

“Last year, we ended up being OK because of the generosity of a number of sponsors,” Beck said. “We were looking at a loss of $800,000.”

He said the financial impact of this year’s cancellation is “too early to tell” but promised the game will return in 2022.

A much more consequential shock to the system would be felt if any of the Playoff games fell to the same fate.

The Playoff risk

Schools and their leagues earned a collective profit of $448 million from bowl games in 2017-18, the last year for which such NCAA data was available to USA TODAY Sports. That NCAA data showed $561 million in bowl payouts, minus $113 million in expenses associated with participating in the games.

But more than 80% of that bowl payout money ($465 million) came from only six games: the Cotton, Peach and Fiesta bowls, as well as the three games of the Playoff that year (Rose, Sugar and championship).

That money then was shared with leagues and teams that did not participate in those games. For example, $15.4 million of Conference USA’s $18.6 million in bowl payout money came from those top-tier games despite its not having a team in them. Nine teams from Conference USA went to lower-tier bowl games that season and racked up a combined $5.2 million in expenses, including UAB in the Bahamas Bowl, according to the NCAA documents. Without that Playoff money, Conference USA would have been $2 million short of covering those expenses.

ESPN is funding most of it by paying $7.3 billion over 12 years for these top games and does so because they attract huge audiences: 19 million on average for the Playoff semifinals last season, ESPN’s third-most watched day ever.

If a Playoff game were canceled this season, it’s not clear how big of a shock it would be to the system. Bill Hancock, the Playoff’s executive director, declined comment, citing confidentiality provisions in the Playoff’s contract with ESPN.

Beck just wishes there was more flexibility built into the system. The way it’s set up now, a game’s fate comes down to a decision at the 11th hour.

“Will there be a different variant next year, or will we learn to live with this?” he asked. “Or can we, as organizations and conferences and the NCAA, come up with better strategies to maybe be able to postpone games or hold for a couple of weeks if something spikes up like this?”

Follow reporter Brent Schrotenboer @Schrotenboer. E-mail: bschrotenb@usatoday.com

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Canceled bowl games shock and warn as College Football Playoff looms