The Redwood Coast: Home to Secret Limestone and 5.14+ Trad

This article originally appeared on Climbing

Far up the coast of California, redwood mist creeps down from the forest to touch ocean cliffs. In the late '90s, eighty feet above Highway 101, Arcata punk Paul Humphrey developed a route with an ocean view. Humphrey attempted to climb the same section of the wall while logging trucks thundered past below. It was his first-ascent debut, the start of his addiction. He finally strung the moves together after discovering a hidden pocket. Then a hold broke, and he whipped back to where he started. Just like Sisyphus, he returned the next day with a purpose.

"Two kneebars and a scream saw me through," Humphrey later wrote in a trip report. "I tried so hard when I finally pulled the move, I felt as if I had not just climbed up, but into the stone. For a brief moment, the rush was perfect. The drug took over, and I could no longer distinguish myself from the rock and moss."

Humphrey went on to bolt endlessly, until he was out of skin and out of cash. But his contributions in the '90s weren't the first routes to grace Redwood Coast rock. Climbers had been exploring Humboldt's beach sea stacks since the '60s; sport climbing simply brought a new appreciation--and vision--to the area.

The Redwood Coast climbing area covers all of Humboldt County and bleeds into the adjacent counties. To the north, it reaches Del Norte County, and to the east into Trinity County. Turns out, the redwood curtain hiding cannabis farms for so long was also hiding superior limestone crags. Though some crags are just a stone's throw from the highway, Redwood Coast climbing is overwhelmingly remote and seldom trafficked, with hours of winding curves up the 101. In this corner of California, you'll catch sights of whales from the anchors; the access to oceanic landscapes with perfect stone and no crowds is unmatched.

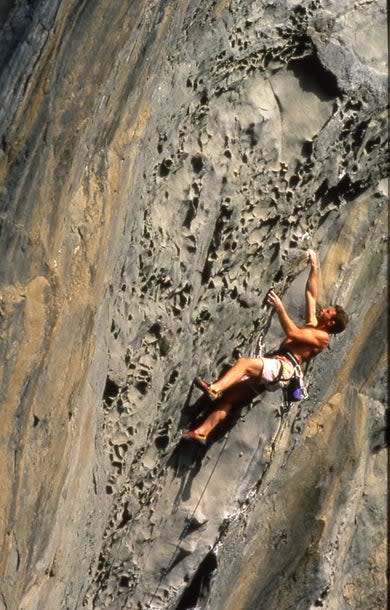

Pro climber Ethan Pringle has climbed some of the hardest routes in the world and established several of his own, including along the Redwood Coast. Humboldt is just a four hour drive from his home in The Bay, and it's where Pringle boasts a handful of unrepeated 5.14 first ascents, tucked away at crags like Cecileville Bluffs. "Cecileville Bluffs is like a little piece of France in Northern California," Pringle said. "The limestone up there is like second to none in the state."

The Redwood Coast hosts just under 1,000 routes on sandstone, quartzite, granite, and limestone. The desolation of the area adds a bit of adventure to the Redwood Coast climbing scene, but it is more than made up for in a lack of crowds and quality of climbing. The following four routes highlight the history of climbing in the region, told through the stories of the people who developed them.

California Coast (5.13a X), Sue Meg State Park

In the late '60s, two Humboldt State University students founded the Boot'n'Blister Club, a group for amateur adventurers looking to explore the sea of hills in the Humboldt area. Bruce Price had just returned from military service in Europe after WWII to attend Humboldt State University. He learned to climb in the European Alps in the military. Back in Humboldt, Price hauled hiking enthusiasts to the rocky shores and up steeply forested hills. He developed routes and recruited new climbers in the early ages of the sport. One of his recruits was fellow Humboldt student Frank Jager.

Price and Jager developed 100-foot aid routes, A3 and A4, on Humboldt beaches. They didn't consider the coastal climbing much more than practice for the "real stuff": multi-pitch aid routes in Yosemite and the Trinity Alps. Regardless, these short routes laid the foundation for Price's later career as a Yosemite regular, and the aid climbs he developed with Jager are now beginner-friendly top-rope classics.

"We were early climbers here, but I’m sure we weren’t the first," Jager said. Jager and Price found anchors along the coastal crags north of Arcata, California, in Sue Meg State Park. It was unclear if mystery climbers of yore bolted them or if surveying conservationists left them. Of course, the Yurok people have held the rocks and land of Sue Meg in reverence for centuries. Jager and Price developed top-rope routes on Karen Rock at Moonstone Beach and at Sue Meg State Park. Today, Karen Rock is so popular on weekends that the crag appears lashed tightly to the beach, with top ropes strung from every anchor.

Jager and Price led California Coast as A3+ in 1968. In their day, they climbed up the steep face with a series of precarious piton placements. The likelihood of decking was high. On aid, this route is trickiest at the start with the relief of a thin crack at the end. The opposite is true for modern-day free climbers. The crack is a great host to slim pitons but useless for free-climbing fingers. The lower section goes at 5.12-, thanks to plentiful face holds, while the upper third is a technical and relentlessly crimpy 13a. Modern route developer and local guidebook author Evan Wisheropp attempted to revive the route after 40 years. "The fact that those guys aided the route and survived is inspirational. I still wondered if the route could go free, so I tested the gear placements on top rope and found that, without pitons, it couldn't be aided at less than C4+," Wisheropp said. "I resorted to freeing on top rope, which was still so special to climb such a beautiful face, but it leaves the nagging question of if it will ever go free on lead."

Blackbeard's Tears (5.14c), Promontory

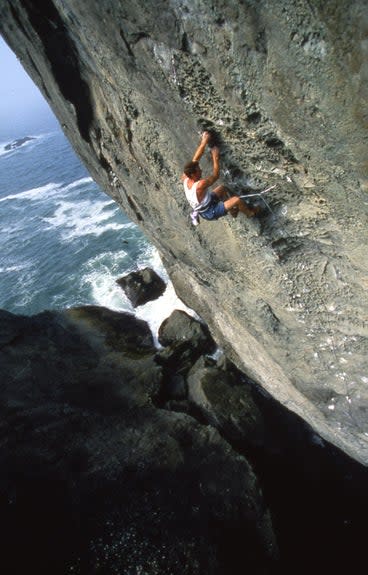

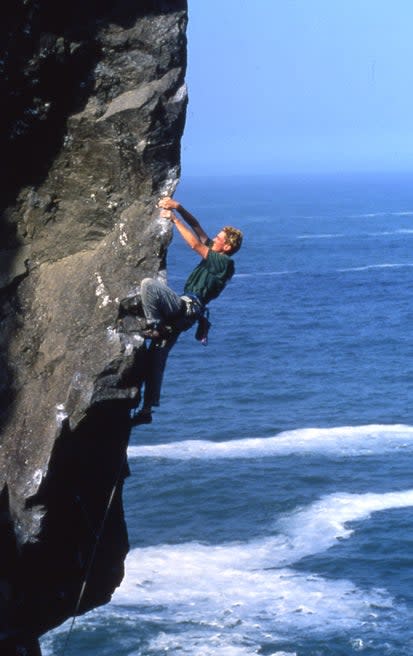

At Promontory, tilted hallways of slab travel down to the ocean. The high tide splashes and crashes at increasingly uneasy belayers. Seeing the main wall of tafoni pockets will give any climber trypophobia. Down each corridor, one wall offers techy slab while the other overhangs.

In 1986, the Greenstone routes at Sue Meg were not enough to keep local climbers busy. Matthias Holladay drove up to Klamath, California, to climb at the locals-only spots. On his adventures, he found a crag north of the Klamath River's mouth along the 101. A walk along the beach and by a fjord across Wilson Creek, and then Holladay was exploring giddily through the other-worldly corridors of Promontory; honeycombed pockets, steep splitters, and textured crimps adorned each wall.

Holladay climbed Blackbeard's Tears on aid during an early foray and ran back home to tell his skeptical climbing buddies about it. Alongside Mark Petrolingo, Rick Shull, Richard Ludwig, Tim Wilhelmi, and Doug Lafarge, Holladay would later introduce modern sport climbing to the area in the late '80s, developing several now-classic areas. But as free-climbing standards rose during that era, Holladay would often wonder if Blackbeard's Tears would ever be freed.

Blackbeard's Tears splits into three efforts: a slightly overhanging 5.10+ that serves as a warm up; an ever-steepening 5.13c splitter up clean, burnished stone; and a 5.14c outro with, reportedly, a wild V11 bulge. Ethan Pringle, who would make the first free ascent in 2016, called the line "one of the sickest single-pitch rock climbs I’ve ever seen." This route proved that the Redwood Coast holds world-class climbing; at the time it was one of only two 5.14c crack climbs in the world. "I would love it if more expert climbers went and tried my routes," Pringle said. " I have almost ten 5.14's in Northern California, and none of them have seen a repeat."

View this post on Instagram

Put Up or Shut up (5.10b), Trinity Aretes

East of Highway 101, 1,500 miles of streams carve through the land, bubbling and rushing beneath long outcrops of bullet limestone. The approach gatekeeps the inland crags with a two-hour drive from Arcata up road-sick curves of Highway 299. Dilapidated buildings and small towns brandish "Bigfoot Country" signs along the way. As the car turns each corner, keep your eyes up. These crags sit high on the hill staring climbers down from their perch.

Eric Chemello was a Humboldt student turned local. He'd sent all the coastal routes from the '70s and, by the mid '90s, was growing tired of the area."I was going down to Vegas every winter, Red Rock and all that," he said. "I was getting ready to move to Vegas. That’s when Humphrey found the Trinity Aretes--and then I wasn't going anywhere. I was sold."

Humphrey was another local climber who clung to Humboldt rock after graduation. He was committed to NorCal crags, seeing adventure and opportunity in Humboldt's hills where few others did. While working at the local Adventure's Edge gear shop, Humphrey would scour maps and drive out to inspect potential crags. He adventured through rough mountain roads hoping to avoid warning shots from many illegal grow operations. It was during this fervent period that Humphrey diagnosed himself with AAD: ascension addiction disorder.

The Trinity Aretes stayed cool in the summer, and Cecilville Bluffs stayed warm in the winter. Now, Redwood Coast climbing was on year round. The Aretes are steep and loom over the Trinity River. They are comprised of blue limestone, where every hold is unique and houses some of the area's highest-quality stone; holds of every shape and texture abound, from popcorn bubbles to velcro pockets and sharp flaky crystals.

"Paul Humphrey really just took the ball and ran with it," Chemello said. "It was his vision, and tenacity, and perseverance of driving around looking and finding all these crags. His crowning achievement wasn't necessarily a difficult route. It was Put Up or Shut Up."

In the late '90s, Humphrey and Chemello prioritized onsight climbing, leaving whatever didn't click right away. They left a legacy of great routes and set the next generation of climbers up for success. Humphrey wrote about and photographed everything. He left a well-documented history on a site doomed to be shut down by 2019. He spent time defending his routes from critics who never contributed but always complained. They complained about too few bolts, too many bolts, too much cleaning or not enough, the bolts that were too high or low. It seemed he could never please everyone. He made climbing accessible but not unchallenging. Humphrey bolted with ethics, painting bolts to keep them invisible, and avoiding over-bolting rock faces. His choices received critique just as any niche internet community gives. Driven by spite, Humphrey hauled out to the Trinity Aretes to make a statement.

"He did the first ascent on lead, carrying a drill, peaking out on psychedelic mushrooms," Chemello said, recalling holding the other end of the rope. "And then, when he finished it, he just called it Put Up Or Shut Up." Humphrey wrote about the psychedelic experience on the climber's forum SuperTopo under the name DisasterMaster.

"I traversed up and left until I found myself floating above the lip of a gaping limestone grotto's ceiling," Humphrey said. "I stuck my pinky into a small air-bubble pocket and twisted my hand until the knuckle jammed in the diminutive hole. Leaning back, I let a single knuckle take my weight." Humphrey monoed a limestone pocket with a 9-pound drill hanging from his shoulder.

The effort and ethic Humphrey put into Put up or Shut up shows. It isn't the most-traveled climb at the crag, but its lore is infamous and it is a classic local's "tick."

My Up and Down Life (5.11b), Marble Caves

Humphrey's climbing buddies described him as a true punk. He matched the eclectic Arcata scene with his bright blue and pink mohawk. He always wore a leather jacket and called himself the Disaster Master. But by 2004, having spent countless hours on sunny cliffs, the sun exposure came back to bite him. Tests for an innocent-looking mole returned as melanoma. Instead of progress on his climbing projects, he wrote about the progress of experimental treatments. He wrote a trip report on SuperTopo titled My up and down life that followed Humphrey through years of loss. "The cancer had been caught in the nick of time, and the wounds were healing, but my mind was still reeling," Humphrey said. "Once again, I sought solace in stone." Instead of facing his problems, he escaped to crags and developed My Up and Down Life.

Humphrey faced a financial struggle after medical bills and a decade's worth of bolts weighed on his credit card. Armed with a crossbow and a rope, he returned to work as a surveyor climbing trees and searching for an arboreal vole in California and Oregon old growth. One day, while perched 80 feet up a tree, he heard a gut-wrenching snap! as the branch supporting his line buckled.

"I was going all the way, 80 feet, no stops," Humphrey said. "My mind lit up. I saw no images of my life, no white light. I saw Christopher Reeves, former Superman, in his wheelchair breathing through a tube in his throat." Gravity became his kryptonite on the journey down. Humphrey's spine caught his fall. His spine fractured, his rib cage broke, and his L2 vertebrae shattered. Hours later he was loaded as cargo enroute to the hospital.

"The bolter had become the bolted," Humphrey said. His spine was in two pieces and held together with titanium bars and screws. "It felt like I’d had the Peter Pan beat out of me. My pixie dust was used up. So this is true pain." Humphrey lived in a custom torso cast clad in stickers like a college student's Subaru. A cocktail of opiates and beer defined his life for a while, until the memories of flowing up vertical rock returned and he resolved to climb again.

Humphrey did climb again, for a while, until 2010 when his cancer returned and spread everywhere. He started a forum called "Malignent [sic] Melanoma Survivors who climb" where he recorded his treatments. He returned to the thread for years to warn others, crowdsource solutions and ponder mortality. He wrote poems and articles about climbing. Humphrey left a vast digital record of recommendations, beta, and trip reports on climbing the Redwood Coast.

He fought to climb but grew weaker. His 5.7 efforts began to feel like 5.11 efforts. He struggled to carry his trad rack from car to crag. His posts expressed frustration with a slow death. The community wrote to check in and tell him of the climbing world. To let him know how all his routes are doing.

On July 29, 2011, Paul Humphrey died at 39 years and eight months. He left an immense legacy, not the least of which was a habitat for Humboldt climbers.

"Climbers who call Humboldt home do so for more than the rock," Humphrey said. " After all, there’s no other place like it. Climbers live and play here for the sunsets and the camaraderie. They climb because pursuit of the sport itself draws them out for a walk through the redwoods to find routes."

Humphrey spent his time in Humboldt stepping off the beaten path. He inspired a local climbing culture to remain offbeat and in touch with the unknown, peeking around cliff-side corners and venturing further into the redwood curtain. Nowadays, people rarely have the opportunity to discover their own adventure. Humphrey spent his life building access to these novel opportunities. Whether climbing in the ocean spray above the Pacific or deep in the woods on blue-streaked limestone you're sure to have a unique experience.

Ollie Hancock (they/them) is a freelance journalist and recreational climber based in Arcata, California. They organize events to uplift trans climbers in their community with an emphasis on building access for marginalized communities.

Also read:

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.