He Rapped off the End of His Rope on Astroman… and Survived

This article originally appeared on Climbing

This article appeared in Rock and Ice issue 254 (November 2018).

After a number of near-death experiences, I am unsure of why others have been taken, yet I remain. Is there some order or higher power at play, or is everything random? Did Lachesis fail to draw my lot and stay Atropos's scissors? The threads on which we spin are uncertain and fragile.

In 1980, I was putting in a belay at the top of the crux pitch of the Super Couloir on Mt. Blanc du Tacul, with almost 300 feet of 9 mm rope out, when my crampons sheared, and I fell. I had placed a few nuts in the 30 feet above the start of the pitch, but had run it out in the ensuing vertical pillar of slush until finally placing a #1 Arrowhead in a shallow, bottoming crack. Dropping through the air, I calmly recognized that if the pin pulled, I would fall nearly 500 feet. My partner, Robb Kimbrough, was anchored to a single crappy pin (I had forgotten the pin rack). He had no idea I had placed the Arrowhead above the pillar. When he heard me scream, he believed the fall was likely to rip the entire pitch, followed by the anchor.

The Arrowhead held. After dropping 80 feet, I spun face down at the top of the pillar looking at Robb, both of us ashen, the couloir dropping a thousand feet to the glacier.

A couple of years later, while soloing the third pitch of Tagger (5.10) in Eldo, I froze at the lip of the eight-foot roof, 200 feet up. Incapable of downclimbing statically, I climbed halfway back in and jumped to latch a big hold at the start of the roof.

***

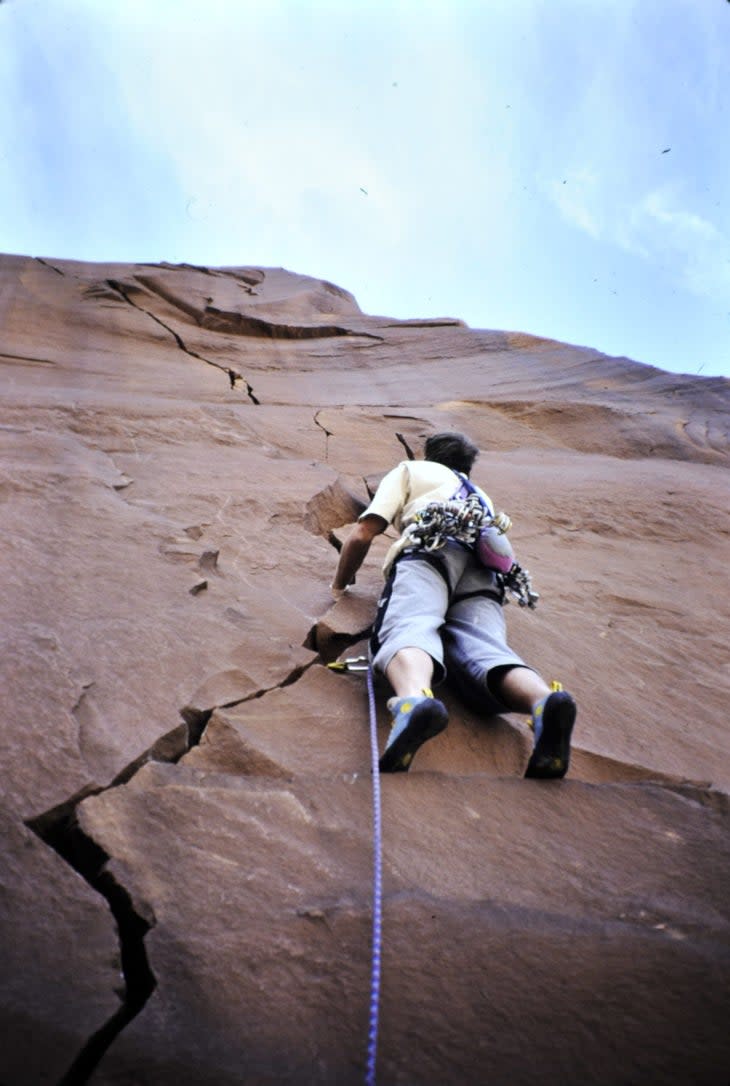

In Yosemite in 1975, Bachar, Kauk and Long (the fact that no first names or further identification is needed confirms their status as giants) freed the East Face of Washington Column, establishing Astroman (V 5.11c). Despite having been free-soloed by a few superstars (Croft, Potter, Honnold), the route even today holds its stature as an outstanding and difficult free climb.

In May 1985, I graduated from law school and in early June found myself road-tripping to the Valley with Big Bruce, my constant climbing partner in law school, at least when we could get out. Bruce was a wide- crack master, fists bigger than his knees. He was solid and, more important, funny, kind and encouraging. We drove his eight- foot boa constrictor (in a cage!) across the country, stopping along the way to feed it a rat, before landing in the Valley. The forced march of law school coupled with 80-plus- mile running weeks had left me wiry, strong and hungry to climb. Within a few weeks after graduation, I was climbing as well as I ever had. Bruce and I dispensed with the Rostrum and the Nabisco Wall and headed to Astroman. We were the sole party anywhere.

The approach scrambles up to the north, gaining altitude. By the time you traverse on slabs to begin the route, the Valley is 1,000 feet below, the lower portion of the Column falling away, creating instant exposure. Below the third pitch, aka the "Boulder Problem," we stood on a ledge with a rat's nest of webbing wrapped around a flake.

Messy, I thought. Someone should have cleaned this up.

The ledge sloped gently, precipitously away. I managed the Boulder Problem and, in one of my proudest moments, the Enduro Corner above. The sun shone. Clotho, one of the three gods of fate in Greek mythology, spun her thread into an endless future. What could go wrong? We were young, strong, immortal.

The Harding Slot was rated 5.8. How hard could it be? I did the difficult lead- in moves, flopped into the Slot, and contemplated the constricting darkness above. Then I struggled for more than an hour to slither through. No amount of compression, exhalation, twisting or turning got me through the defile. Anyone who climbs the Harding Slot comes out changed: physically, mentally or both. There is no doubt in my mind it is the route's crux. My existential struggle, despair, swearing, panic and ultimate defeat led Bruce, who had 30- plus pounds on me, to decline my invitation to take over the lead. There was nothing for it but to rappel.

Also Read

Two uneventful raps led to Overnight Ledge. The day had changed, the lighthearted early-morning sun waning. Thermal breezes emanated from the Valley floor. The temperature fell. We were utterly alone.

Looking down from the ledge, I did the math. The Corner was about 140 feet and the Boulder Problem pitch not more than 30 or so. Our two ropes should just reach that sloping tatty ledge below the Boulder Problem, and from there two more raps would gain the ground. Tying knots in the end of each rope, I tossed them straight off Overnight Ledge into the void. As I reached a point about 20 or 30 feet below the ledge, the geometry of the wall became more apparent. The ends of the ropes hung well out from the wall. Rapping the fall line would leave me suspended 20 feet out. At about 60 or 70 feet down, I began to push gently away from the wall with my feet to pendulum to return to the wall and prevent becoming suspended in space.

Thermals rose. It was unnervingly quiet. I could not see or hear Bruce above me. Out of touch and becoming more so. I continued down--carefully, fearfully--as the vectors pushed me farther and farther from the wall. I pushed harder each time I swung back in to retain the arc that provided at least minimal contact.

It was 1985, and the ropes ran through my rappel device without backup. I wrapped the ropes behind my leg for extra friction. I could see the sloping postage-stamp ledge with its ugly tat at the base of the Boulder Problem pitch, about 40 feet below. The ropes--a single overhand knot in the end of each, but not tied together--did not quite reach. I had no prussiks or cordelette, just a few cams and slings.

In and out. I continued to push away from the wall, the apogee now 15 to 20 feet out. The afternoon shade darkened. The wind swirled.

In hindsight, it is so obvious (isn't everything?): I should have stopped and used what slings I had to prussik back up. But the rope ends now seemed almost to reach the sloping ledge. If I rapped to the end and rested on the knots, with stretch, I might be able to swing in and grab the rat's nest.

But, looking down, I could see that the knot in one of the ropes had come undone. The second appeared intact, albeit loosely. In those ticking seconds, I thought maybe the remaining knot would jam in my rappel device and allow me to swing in and grab the anchor. In retrospect, this might have happened had the stopper knot been on the correct rope. Then the knot joining the ropes together way above would jam in the rappel anchor. But if the remaining knot on the rope end was on the wrong rope, the ropes would simply pull through.

And none of it mattered now because-- how did this happen?--both ropes pulled through my rappel device. I had been clenching hard with the left hand before that, and now thrutched desperately to grab the remaining inches of the rope ends with both hands. So stupid. So futile. The ledge spun below. It would only be a few seconds before my hands opened and Atropos released me to eternal ground.

I could barely reach the wall now in my pendulum arc. My final act: I kicked away from the wall with one foot. Instead of maintaining the previous controlled arc, to and fro, this final, forceful thrust pushed me over 20 feet away from the wall and spun me around. Half Dome twisted into sight, then the wall. Hundreds of feet below, the ground fell far away to the Ahwahnee.

I tunneled my focus to only the ledge and that messy anchor. This is it. Now! I held both ropes with only my left hand and lunged desperately for the rat's nest with my right. I was 6-foot-2 with a plus-2-inch wingspan. Even then, I only just latched it as my feet swung down and smacked the slab. I jammed my arm through the webbing and hung by the crook of my elbow, hyperventilating, left hand still managing to hold the rope ends.

I couldn't move. Couldn't clip the anchor.

After long minutes, my heart rate slowed, the trembling abated, and I clipped in. A few more minutes, and I tied long slings to the tails of the ropes so I could pull Bruce in when he arrived. Eventually, I screamed, "Off rappel!"

As Bruce came into sight, he looked down, and I could see him trying to piece it all together. The slings were tied to the ends of the ropes; the ropes dangled well out from the wall. I pulled him in.

"What the hell happened?" he asked. It all poured out, the whole awful, inept story.

"Oh, my god," he gasped. "I can't believe it. I'm glad you're alive."

I was, too. But unsure of why. My actions and decisions certainly warranted a different outcome. Lucky, I guess. We carefully rigged the final two rappels and staggered to the Valley floor.

Got an epic? Please submit your story to the climbing team at, queries@outsideinc.com

Michael Gilbert,

an attorney living in Louisville, Colorado, is a longtime climber and skier who has also discovered the joy of golf.

Also Read

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.